The mining encampment that stretches across a mountainside in Brazil’s Amazon is dotted with plastic tarpaulin covers. Under them, dozens of men toil in rocky pits, excavating sacks of ore to be transported by truck. Gold will be extracted from the ore.

Of all places this squatter settlement shouldn’t exist, it’s here: in Brazil’s northernmost Roraima state that doesn’t permit gold prospecting, inside one of the nation’s Indigenous reserves where mining activity is illegal and on the flanks of this mountain – Serra do Atola – that traditional leaders of the Macuxi people hold sacred.

Nevertheless, a recent visit by The Associated Press – at the invitation of local leaders from the Maturuca and Waromada villages – found the illegal mining site back up and running just months after authorities shut it down.

FILE - Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro raises a "borduna," a traditional Indigenous weapon, outside Planalto presidential palace after receiving it as a gift from Indigenous people from various regions who support agro-business activities on Indigenous lands, in Brasilia, Brazil, Aug. 12, 2021. Bolsonaro has said that Indigenous people should be entitled to self-determination -- not just regarding possible mining, but all activities. (AP PhotoEraldo Peres, File)

That the miners have returned in droves underscores the insatiable lure of gold and the fact they are being encouraged to keep up their work – including by the nation’s president.

Such relentless pressure is rekindling long-standing divisions in local communities here on the Raposa Serra do Sol reserve about the best path forward for their collective well-being. Some local leaders see gold mining and other extractive activities as a potential boon for the area that could bring jobs and investments in one of Brazil’s poorest states. Others see the mining as defiling the land on the reserve by polluting the waters, stripping bare the land, as well as upending centuries-old cultural traditions.

An AP investigation found that illegal landing strips and unauthorized airplanes have helped miners carry out tons of gold mined on Indigenous lands. The gold ends up in the hands of brokers, some of whom are under investigation by authorities for receiving gold from illegal mining. The gold is refined in Sao Paulo before becoming part of the global supply chain where it is used in products such as smartphones and computers.

The Maturuca community where members of the Macuxi ethnic group live on the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous reserve in Roraima state, Brazil, Saturday, Nov. 6, 2021. Illegal gold mining on Indigenous territory like this one is rekindling long-standing divisions in local Indigenous communities about the best path forward for their collective well-being. (AP PhotoAndre Penner)

Last March, the Amazon military command, federal police and environmental agencies raided mining operations at Serra do Atola mountain and found 400 people, excavation pits, precision scales and mercury for gold processing. Tribal leaders had previously filed complaints to prosecutors of bars, drugs and prostitution at the sacred site’s base.

The mining site is just one of several. The number of wildcat miners at sites across the reserve has surged to some 2,000, according to Edinho Batista Macuxi, general coordinator of Roraima’s Indigenous Council, the state’s primary representative body that says it represents some 30,000 people.

Macuxi said that the illegal mining operations on the reserve were financed by local non-Indigenous business owners and politicians who were the owners of the equipment needed to extract the gold from the ore. A 2020 Federal Police raid on the reserve - in which four tribespeople were arrested – seems to support those allegations. The police found the gold illegally extracted would be split three ways: a quarter would be paid to the owners of equipment used to extract the gold, 4% to the local community where the mining operations were active, and the rest to the miners who had extracted the gold.

A girl from the Macuxi ethnic group plays with baby goats being raised for food for the Maturuca community on the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous reserve in Roraima state, Brazil, Sunday, Nov. 7, 2021. Bordering Venezuela and Guyana, the Indigenous territory is bigger than Connecticut and home to 26,000 people from five different ethnicities. (AP PhotoAndre Penner)

Macuxi attributes the resilience of the illegal activity to the fiery, pro-mining rhetoric of Brazil’s far-right President Jair Bolsonaro. The president has sought to legalize prospecting on reserves across the country, saying they are underutilized and should bring socioeconomic gains to the impoverished region.

“The president is most to blame,” Macuxi told the AP. “There is great incentive coming directly from the state.”

Bolsonaro’s endorsement of mining resonates with those locals who support greater economic development with the support from outsiders, Macuxi said. Some view gold prospecting as beneficial or are involved directly themselves.

Wildcat gold miners transport sacks of rocks out of the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous reserve where gold mining is illegal in Roraima state, Brazil, Saturday, Nov. 6, 2021. Prospectors hope the rocks contain granules of gold. (AP PhotoAndre Penner)

“They are a minority,” said Macuxi. “They are used as puppets to justify these types of projects.”

Bolsonaro has said that Indigenous people should be entitled to self-determination — not just regarding possible mining, but all activities. He publicly opposed Raposa Serra do Sol’s designation as a protected reserve in 2005 and often holds it up as an example of a large swath of land ripe for productive activities.

The president visited the reserve last October and, donning a traditional tribal headdress, shared with a cheering crowd of villagers his plans to present legislation that would allow mining, monoculture crop cultivation and infrastructure projects like dams on reserves.

Indigenous people from the Macuxi ethnic group prepare manioc flour in the Maturuca community on the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous reserve in Roraima state, Brazil, Saturday, Nov. 6, 2021. Indigenous activists argue large-scale farms on Indigenous lands stand to deepen a trend already taking place with illegal mining: meddlers reaping outsize benefits while local communities receive scraps, plus the environmental damages. (AP PhotoAndre Penner)

“This bill is not an imposition. It says if you want to plant, go plant. If you’re going to mine, you’re going to mine,” he told the Flechal community, where illegal mining is also present.

In the background, banners of the Defense Society of the United Indigenous People of Roraima, which supports mining on the reserve, hung on the wall. The group purports to represent 22,000 people across Roraima.

Unlike many reserves in the Brazilian Amazon featuring lush rainforest, Raposa Serra do Sol is mostly tropical savannah. Bordering Venezuela and Guyana, it is larger than the state of Connecticut and home to 26,000 people from five different ethnicities.

FILE - Munduruku Indigenous people from the Alto Tapajos in Para state hold the Portuguese sign "We do not accept entry of the Federal Police on our Alto Tapajos territory," referring the expelling of miners by the Federal Police from Indigenous lands in Para state, outside the Supreme Court to show support for Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro's proposals to allow mining on Indigenous lands in Brasilia, Brazil, April 19, 2021. Some Indigenous leaders see gold mining as a potential economic boon for the area that could bring jobs and investments, while others see it as defiling the land. (AP PhotoEraldo Peres, File)

Since the Brazilian government granted its protected status, it has been a stage for sporadic violence often driven by disagreements over whether non-Indigenous farmers could remain in the territory.

In November, state military police broke up checkpoints established by Macuxi people opposed to the illegal mining; six of them were injured with rubber bullets.

When AP reporters visited the reserve the same month, they still had to pass through checkpoints aimed at warding off invaders and stopping the spread of COVID-19. The rugged terrain is only passable in a four-wheel drive vehicle or motorcycle.

Indigenous from the Macuxi ethnic group play soccer in the Maturuca community on the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous reserve where mining is illegal in Roraima state, Brazil, Saturday, Nov. 6, 2021. President Jair Bolsonaro publicly opposed Raposa Serra do Sol's demarcation in 2005 and often holds it up as an example of a large swath of land ripe for productive activities. (AP PhotoAndre Penner)

The AP also witnessed illegal miners working in pits on the side of the sacred mountain, equipped with barrels of fuel and portable generators used to power jackhammers to break up the rocky surface.

From the encampment, trucks transported sacks of rocks that prospectors hope contain granules of gold to properties outside the mining site.

There, they are put through crushing machines in order to extract gold. In the vicinity, lookouts alert the presence of any unknown or suspicious vehicles.

Women and children from the Macuxi ethnic group watch their family members play soccer in the Maturuca community on the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous reserve in Roraima state, Brazil, Saturday, Nov. 6, 2021. Bordering Venezuela and Guyana, it is bigger than Connecticut and home to 26,000 people from five different ethnicities. (AP PhotoAndre Penner)

Elsewhere in the reserve, in the Mutum community along the Ireng River that forms part of Brazil's border with Guyana, two men sat aboard a mining barge. One held a pan for separating the gold from sediment using mercury. The process is ubiquitous across Brazil’s Amazon and it irreversibly poisons locals’ waterways and fisheries, according to federal prosecutors and decades of research in the region, including by the government’s Fiocruz health institute.

The president of the smaller pro-Bolsonaro Indigenous group, Irisnaide de Souza Silva, has met with the president personally, including in the capital, Brasilia.

She told the AP that her organization is trying to kick-start a project to plant 30,000 hectares (74,000 acres) of soybeans on the reserve.

A young member of the Macuxi ethnic group stand near a horse in the Maturuca community of the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous reserve in Roraima state, Brazil, Sunday, Nov. 7, 2021. Bordering Venezuela and Guyana, the Indigenous territory is bigger than Connecticut and home to 26,000 people from five different ethnicities. (AP PhotoAndre Penner)

“We’re very focused on this project, it’s innovative,” she said.

The farming initiative dovetails with a program that Brazil’s Indigenous agency created under Bolsonaro, dubbed “Indigenous Independence.” It enables rural producers and organizations to partner with Indigenous people within reserves to mass produce crops.

The program has been fiercely criticized by activists who say ancestral lands and traditions should be preserved, and who point out that the expertise and capital come from people outside the reserve.

Tarps set up by people illegally mining for gold dot the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous reserve in Roraima state, Brazil, Saturday, Nov. 6, 2021. The number of wildcat miners at sites across the reserve has surged to some 2,000, according to Edinho Batista Macuxi, general coordinator of Roraima's Indigenous Council. (AP PhotoAndre Penner)

They argue large-scale farms on reserves stand to deepen a trend already taking place with illegal mining: outsiders reaping outsize benefits while local communities receive scraps, plus the environmental damages.

The Indigenous agency's press office confirmed to the AP in an email that it was aware of the proposed soybean project, which isn't part of its “Indigenous Independence” initiative. The agency described its program as a means to help improve villages' living conditions and provide “dignity” to local people.

Critics say that couldn't be farther from the truth.

A man herds goats on the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous reserve in Roraima state, Brazil, Saturday, Nov. 6, 2021. Unlike most reserves in the Brazilian Amazon featuring lush rainforest, Raposa Serra do Sol is mostly tropical savannah. (AP PhotoAndre Penner)

“It’s a contemporary way of doing what the colonizers did in the 16th century and 17th century,” said Antenor Vaz, a former member of the agency, who is now retired and consulting on issues relating to isolated tribes. “What’s really happening is the appropriation of Indigenous lands by outsiders.”

Vaz said that Raposa Serra do Sol could represent the future for Brazil’s Indigenous lands far and wide if Bolsonaro’s development-oriented policies continue.

“Inside any community differences exist,” he added. “Bolsonaro is stoking these differences when he only visits communities inside the territory that are in favor of these projects.”

A Macuxi Indigenous family sits in front of their home in the Maturuca community on the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous reserve in Roraima state, Brazil, Sunday, Nov. 7, 2021. Bordering Venezuela and Guyana, the territory is bigger than Connecticut and home to 26,000 people from five different ethnicities. (AP PhotoAndre Penner)

Follow Cowie on Twitter at @SamCowie84

Contact AP’s global investigative team at Investigative@ap.org or https://www.ap.org/tips/

Wildcat miners work on the Ireng River on the border of Brazil with Guiana, on the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous reserve in Roraima state, Brazil, Sunday, Nov. 7, 2021. An illegal mining site is back up and running just months after authorities shut it down, underscoring the lure of gold and the fact they are being encouraged to keep up their work -- including by the nation's president. (AP PhotoAndre Penner)

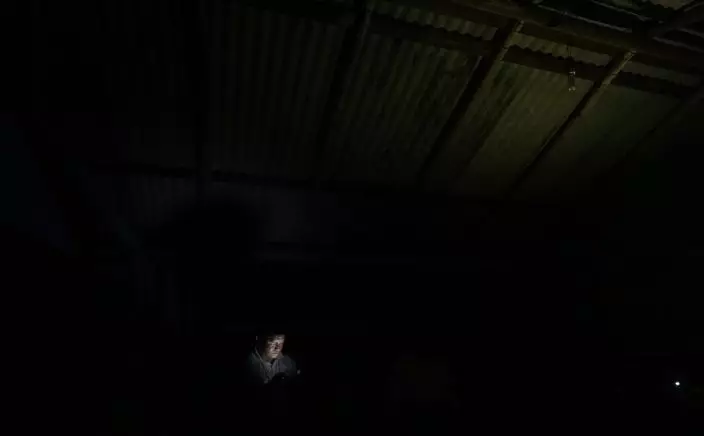

An Indigenous man from the Macuxi ethnic group checks his cell phone in a community building in the Maturuca community on the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous reserve in Roraima state, Brazil, Saturday, Nov. 6, 2021. Illegal gold mining on Indigenous territory like this one is rekindling long-standing divisions in local Indigenous communities about the best path forward for their collective well-being. (AP PhotoAndre Penner)