In Sainte-Anastasie-sur-Issole, a village that curls catlike in verdant Provence hillocks, voters are making an early start on France's presidential election.

From their ballot box this weekend and next will come the name of the candidate — picked from among dozens — that they want their mayor to endorse.

Normally, the choice would be Mayor Olivier Hoffmann's alone, under a right that, at election time, turns small-potato public office-holders into hot properties — wooed by would-be candidates who need 500 endorsements from elected officials to get onto the April ballot.

FILE - A protester places a sticker next to a graffiti that reads "corrupt" on the regional ministry of health, during a demonstration in Marseille, southern France, Saturday, Aug. 14, 2021. The run-up to the April election comes in a context of mounting violence targeting elected officials in France, with holders of public officers targeted for their politics and by opponents of COVID-19 vaccinations restrictions. (AP PhotoDaniel Cole, File)

But in an inflamed climate of election-time politics, and with fury among opponents of COVID-19 vaccinations increasingly bubbling over into violence directed at elected representatives, Sainte-Anastasie's staunchly apolitical mayor doesn't want to be seen taking sides.

Safer, he figures, to let the 2,000 villagers choose for him.

“I know lots and lots of people in the village, many are my friends, I don’t want to create tensions," Hoffmann said in a phone interview. “So no politics.”

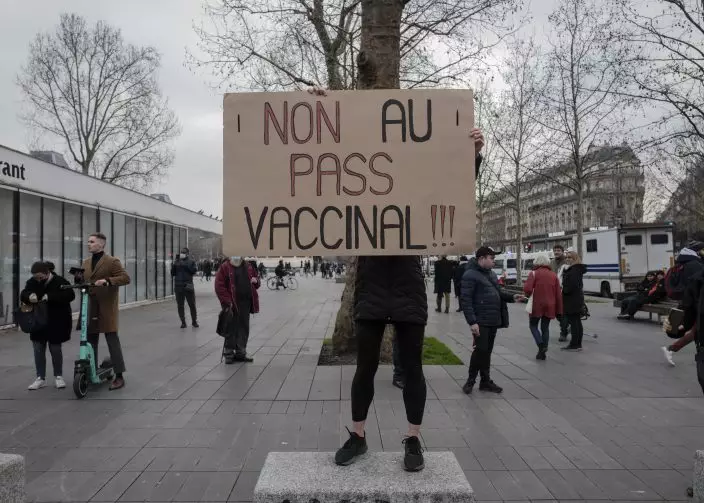

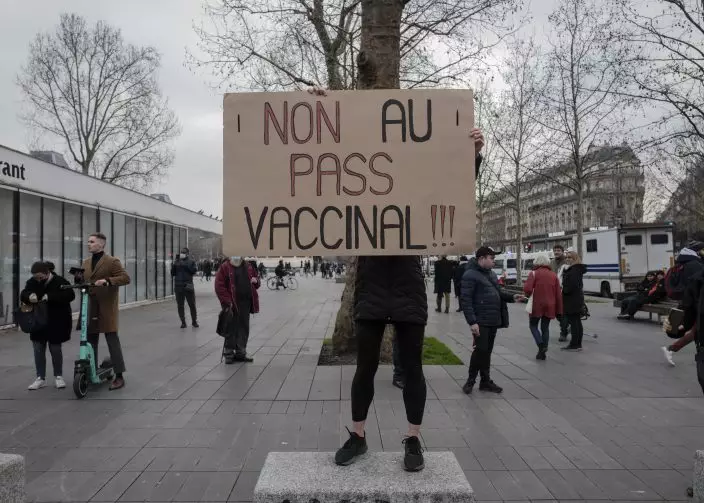

FILE - A demonstrator holds a placard that reads 'No to vaccine pass' in opposition to vaccine pass and vaccinations to protect against COVID-19 during a rally in Paris, France, Saturday, Jan. 22, 2022. The run-up to the April election comes in a context of mounting violence targeting elected officials in France, with holders of public officers targeted for their politics and by opponents of COVID-19 vaccinations restrictions. (AP PhotoRafael Yaghobzadeh, File)

“Politics,” the mayor added, “often do more harm than good."

Even in a country with ingrained traditions of violent contestation, where the revolutionaries of 1789 guillotined King Louis XVI and Queen Marie-Antoinette, an upsurge of physical and verbal attacks and online torrents of hatred directed at public officials — often, now, over COVID-19 policies — are ringing alarm bells.

Violence hasn't approached the level of the storming of the U.S. Capitol by Donald Trump supporters in 2021. Nor have French lawmakers been killed like their counterparts in Britain. There, the fatal stabbing of a Member of Parliament in October prompted renewed national soul-searching about the safety of elected officials with a proud tradition of readily meeting voters.

FILE Demonstrators march in opposition to vaccine pass and vaccinations to protect against COVID-19 in Paris, France, Saturday, Jan. 8, 2022. The run-up to the April election comes in a context of mounting violence targeting elected officials in France, with holders of public officers targeted for their politics and by opponents of COVID-19 vaccinations restrictions. (AP PhotoAdrienne Surprenant, File)

Still, there's mounting disquiet in France in the wake of apparent arson attacks in December that targeted a lawmaker and a mayor, both aligned with President Emmanuel Macron, and other violence targeting elected officials as the government steadily increased pressure on the non-vaccinated to get COVID-19 jabs to curb the surge of infections fueled by the omicron variant.

The Interior Ministry recorded a year-on-year increase of 47% in acts of violence directed at elected officials through the first 11 months of 2021, with 162 lawmakers and 605 mayors or their deputies reporting attacks. Lawmakers say death threats have become everyday occurrences. Titled “decapitation,” an email received by lawmaker Ludovic Mendes in November read: “That's how we dealt with tyrants during the French Revolution."

This month, during protests against France’s vaccine pass that bars the unvaccinated from cafés and other venues, about 30 angry people besieged the office of lawmaker Romain Grau, shoving him and yelling furiously.

“Death! We’ll get you all!!” shouted one man who launched a slap at the lawmaker's head. Grau later told broadcaster TF1 that he feared the confrontation would finish “in a blood bath and a lynching.”

When lawmaker Pascal Bois' garage went up in flames in December, the words, “Vote no” and “It's going to blow!” were spray-painted on an outside wall, which he took as an intimidation attempt before parliamentary passage of the vaccine pass this month.

The National Assembly president, Richard Ferrand, says more than 540 of the 577 lawmakers have reported threats or verbal and physical attacks.

“France isn't bathed in fire and blood. These are acts of brutal minorities," Ferrand told the parliamentary TV channel this week. “Still, it seems to me that we have ratcheted up a notch, expressing a rage that is new.”

Anti-vaccination sentiment is also dovetailing with residual anger among “yellow vest” protesters. Their frequently violent demonstrations against Macron rocked his government before the pandemic. Recent protests against COVID-19 measures have again seen some demonstrators wearing yellow vests.

When Bernard Denis was jolted awake by a loud boom in the middle of the night in December, the mayor of the Normandy village of Saint-Côme-du-Mont discovered his cars on fire and the words, “The mayor supports Macron," daubed in black on a wall.

Also written was “Zemour president” — a misspelt apparent reference to presidential candidate Eric Zemmour, a far-right rabble-rouser with repeated hate-speech convictions.

Around 42,000 elected officials are empowered to sponsor a candidate for the presidential race. The bar of 500 endorsements is intended to whittle down the field. Endorsing a candidate doesn't require agreeing with their politics. Some sponsors simply want a politically broad election choice. But because endorsements are public, they're also not without potential consequences.

In Sainte-Anastasie, Hoffmann is keen to participate. But the mayor wants to avoid any risk of villagers turning on him if he decides alone, of them saying: “'You endorsed him so you support him, you’re this and that, you’re red, yellow, green, blue, blue-white-and-red' or whatever."

Hoffmann is instead pledging to endorse their choice, even if the winner of the ad hoc vote he's organizing isn't aligned with his own politics, which he keeps to himself. In the 2017 presidential run-off that Macron won, the village voted by a large majority for the loser, far-right leader Marine Le Pen, who is running again.

Villagers will choose from around 45 would-be candidates, including Macron, who Hoffmann assumes will seek re-election even though the president hasn't yet said so.

And thus, Hoffmann hopes, harmony will reign in what he calls “the village of my heart."

“I want to give it, my village, everything I have," he said, "and I don’t want politics to encroach on that."

Follow all AP stories on the pandemic at https://apnews.com/hub/coronavirus-pandemic

President Emmanuel Macron is in the pole position to win reelection Sunday in France's presidential runoff, yet his lead over far-right rival Marine Le Pen depends on one major uncertainty: voters who decide to stay home.

A victory in Sunday's runoff vote would make Macron the first French president in 20 years to win a second term.

All opinion polls in recent days converge toward a victory for the 44-year-old pro-European centrist — yet the margin over his nationalist rival appears uncertain, varying from 6 to 15 percentage points, depending on the poll.

FILE - Centrist candidate and French President Emmanuel Macron shakes hands to residents after a campaign rally Friday, April 22, 2022 in Figeac, southwestern France. French President Emmanuel Macron is in pole position to win reelection Sunday, April 24, 2022 in France's presidential runoff. Yet his lead over far-right rival Marine Le Pen depends on one major uncertainty: voters who decide to stay home. A victory in Sunday’s runoff vote would make Macron the first French president in 20 years to win a second term. (AP PhotoChristophe Ena, File)

Polls also forecast a possibly record-high number of people who either vote blank or stay at home and don't vote at all in this second and final round.

The April 10 first-round vote eliminated 10 other presidential candidates. Who becomes France's next leader will largely depend on what people who backed those losing candidates do on Sunday.

The question is a hard one, especially for leftist voters who dislike Macron but don’t want to see Le Pen in power either. A second term for Macron relies in part on their mobilization, prompting the French leader to issue multiple appeals to leftist voters in recent days.

FILE - French far-right leader Marine Le Pen poses for a selfie with supporters during a campaign rally in Perpignan, southern France, Thursday, April 7, 2022. French President Emmanuel Macron is in pole position to win reelection Sunday, April 24, 2022 in France's presidential runoff. Yet his lead over far-right rival Marine Le Pen depends on one major uncertainty: voters who decide to stay home. A victory in Sunday’s runoff vote would make Macron the first French president in 20 years to win a second term. (AP PhotoJoan Mateu Parra, File)

"Think about what British citizens were saying a few hours before Brexit or (people) in the United States before Trump's election happened: ‘I’m not going, what’s the point?’ I can tell you that they regretted it the next day,” Macron warned this week on France 5 television.

“So if you want to avoid the unthinkable ... choose for yourself,” he urged hesitant French voters.

The two rivals both appeared combative in the final days before Sunday's election, including clashing Wednesday in a one-on-one televised debate.

FILE - Centrist presidential candidate and French President Emmanuel Macron holds hands to residents during a campaign stop Thursday, April 21, 2022 in Saint-Denis, outside Paris. French President Emmanuel Macron is in pole position to win reelection Sunday, April 24, 2022 in France's presidential runoff. Yet his lead over far-right rival Marine Le Pen depends on one major uncertainty: voters who decide to stay home. A victory in Sunday’s runoff vote would make Macron the first French president in 20 years to win a second term. (Ludovic Marin, Pool via AP, File)

Macron argued that the loan Le Pen’s party received in 2014 from a Czech-Russian bank made her unsuitable to deal with Moscow amid its invasion of Ukraine. He also said her plans to ban Muslim women in France from wearing headscarves in public would trigger “civil war” in the country that has the largest Muslim population in Western Europe.

“When someone explains to you that Islam equals Islamism equals terrorism equals a problem, that is clearly called the far-right,” Macron declared Friday on France Inter radio.

In his victory speech in 2017, Macron had promised to “do everything” during his five-year term so that the French “have no longer any reason to vote for the extremes.”

FILE - Centrist presidential candidate and French President Emmanuel Macron wears boxing gloves as he campaigns in the Auguste Delaune stadium Thursday, April 21, 2022 in Saint-Denis, outside Paris. French President Emmanuel Macron is in pole position to win reelection Sunday, April 24, 2022 in France's presidential runoff. Yet his lead over far-right rival Marine Le Pen depends on one major uncertainty: voters who decide to stay home. A victory in Sunday’s runoff vote would make Macron the first French president in 20 years to win a second term. (AP PhotoFrancois Mori, Pool, File)

Five years later, that challenge has not been met. Le Pen has consolidated her place on France's political scene, the result of a years-long effort to rebrand herself as less extreme.

Le Pen's campaign this time has sought to appeal to voters struggling with surging food and energy prices amid the fallout of Russia’s war in Ukraine. The 53-year-old candidate said bringing down the cost of living would be a top priority if she was elected as France’s first woman president.

She criticized Macron's “calamitous” presidency in her last rally in the northern town of Arras.

FILE - Emma Mino holds an electoral poster of French far-right presidential candidate Marine Le Pen, Tuesday, March 29, 2022 in Le Temple-De-Bretagne, western France. French President Emmanuel Macron is in pole position to win reelection Sunday, April 24, 2022 in France's presidential runoff. Yet his lead over far-right rival Marine Le Pen depends on one major uncertainty: voters who decide to stay home. A victory in Sunday’s runoff vote would make Macron the first French president in 20 years to win a second term. (AP PhotoJeremias Gonzalez, File)

“I'm not even mentioning immigration or security for which, I believe, every French person can only note the failure of the Macron’s policies ... his economic record is also catastrophic,” she declared.

Political analyst Marc Lazar, head of the History Center at Sciences Po, told the AP he thinks that Macron is going to win again. Le Pen "has this lack of credibility," he said.

But if Macron is re-elected, "there is a big problem," he added. “A great number of the people who are going to vote for Macron, they are not voting for this program, but because they reject Marine Le Pen.”

He said that means Macron will face a “big level of mistrust” in the country.

Macron has vowed to change the French economy to make it more independent while protecting social benefits at the same time. He said he will also keep pushing for a more powerful Europe.

His first term was rocked by the yellow vest protests against social injustice, the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine. It notably forced Macron to delay a key pension reform, which he said he would relaunch soon after reelection, to gradually raise France's minimum retirement age from 62 to 65. He says that's the only way to keep benefits flowing to retirees.

The French presidential election is also being closely watched abroad.

In an opinion piece Thursday in several European newspapers, the center-left leaders of Germany, Spain and Portugal urged French voters to choose him over his nationalist rival. They raised a warning about “populists and the extreme right” who hold Putin “as an ideological and political model, replicating his chauvinist ideas.”

A Le Pen victory would be a “traumatic moment, not only for France, but for European Union and for international relationships, especially with the USA," Lazar said, noting that Le Pen "wants a distant relationship between France and the USA.”

In any case, Sunday's winner will soon face another obstacle to be able to govern France: A legislative election in June will decide who controls a majority of seats in France's National Assembly.

Already, the battles promise to be hard-fought.

AP Journalists Catherine Gaschka and Jeffrey Schaeffer contributed to that story.

Follow AP’s coverage of the French election at https://apnews.com/hub/french-election-2022