KADUNA, Nigeria (AP) — His weak body stood in the doorway, exhausted and covered in dirt. For two years, the boy had been among Nigeria’s ghosts, one of at least 1,500 schoolchildren and others seized by armed groups and held for ransom.

But paying a ransom didn't work for 12-year-old Treasure, the only captive held back from the more than 100 schoolchildren kidnapped from their school in July 2021 in the northwestern Kaduna state. Instead, his captors hung on, and he had to escape the forests on his own in November.

Click to Gallery

FILE- Jummai Mutah, left, and Amina Ali, Chibok schoolgirls who were kidnapped in 2014 by Islamic extremists and later released, attend a 10th anniversary event of the abduction in Lagos, Nigeria, Thursday, April 4, 2024. Their experience represents a worrying new development in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country where the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region. (AP Photo/Mansur Ibrahim, File )

Mary Peter, mother of Jennifer Peter, who was kidnapped with others in her school by gunmen in March 2021, listens to a question during an interview with The Associated Press in Kaduna, Nigeria, Tuesday , March, 26, 2024. The gunmen who kidnapped Jennifer Peter and dozens of her peers from school in March 2021 returned months later to attack another school in her state in northwestern Nigeria. The second time, they seized over 100 children including Jennifer's 10-year-old cousin, Treasure, who was held captive for more than two years. (AP Photo/Chinedu Asadu)

Mary Peter, mother of Jennifer Peter, who was kidnapped with others in her school by gunmen in March 2021, sobs during an interview with The Associated Press in Kaduna, Nigeria, Tuesday, March, 26, 2024. The gunmen who kidnapped Jennifer Peter and dozens of her peers from school in March 2021 returned months later to attack another school in her state in northwestern Nigeria. The second time, they seized over 100 children including Jennifer's 10-year-old cousin, Treasure, who was held captive for more than two years. (AP Photo/Chinedu Asadu)

Jennifer Peter, who was kidnapped with others in her school by gunmen in March 2021, play with her mobile phone in Kaduna, Nigeria, Tuesday , March, 26, 2024. The gunmen who kidnapped Jennifer Peter and dozens of her peers from school in March 2021 returned months later to attack another school in her state in northwestern Nigeria. The second time, they seized over 100 children including Jennifer's 10-year-old cousin, Treasure, who was held captive for more than two years. (AP Photo/Chinedu Asadu)

Jennifer Peter, who was kidnapped with others in her school by gunmen in March 2021, speaks during an interview in Kaduna, Nigeria, Tuesday, March, 26, 2024. The gunmen who kidnapped Jennifer Peter and dozens of her peers from school in March 2021 returned months later to attack another school in her state in northwestern Nigeria. The second time, they seized over 100 children including Jennifer's 10-year-old cousin, Treasure, who was held captive for more than two years. (AP Photo/Chinedu Asadu)

KADUNA, Nigeria (AP) — His weak body stood in the doorway, exhausted and covered in dirt. For two years, the boy had been among Nigeria’s ghosts, one of at least 1,500 schoolchildren and others seized by armed groups and held for ransom.

FILE- People gather to welcome then-recently freed students of the LEA Primary and Secondary School Kuriga upon arrival to reunite with there parents in Kuriga, Nigeria, Thursday, March 28, 2024. Their experience represents a worrying new development in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country where the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region. (AP Photo/Olalekan Richard, File)

FILE - Security walk past the burned government secondary school Chibok where gunmen abducted more than 200 students in Chibok, Nigeria, Monday, April, 21. 2014. In Nigeria, Africa's most populous country, the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region. (AP Photo/ Haruna Umar, File)

FILE - Freed students of the LEA Primary and Secondary School Kuriga sit upon their arrival at the state government house in Kaduna, Nigeria, Monday, March 25, 2024. Their experience represents a worrying new development in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country where the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region. (AP Photo/Habila Darofai, File)

FILE- Then-recently freed Chibok schoolgirls sit with their children at the Army Maimalari Cantonment in Maiduguri, Nigeria, Thursday, May 4, 2023. Their experience represents a worrying new development in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country where the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region. (AP Photo/Jossy Ola, File)

FILE - Some of the escaped kidnapped girls of the government secondary school Chibok arrive for a meeting with Borno state governor, in Maiduguri, Nigeria, Monday June, 2. 2014. Their experience represents a worrying new development in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country where the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region. (AP Photo/Jossy Ola, File)

FILE - Freed students of the LEA Primary and Secondary School Kuriga leave a van upon arrival at the government house in Kaduna, Nigeria, Monday, March 25, 2024. Their experience represents a worrying new development in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country where the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region. (AP Photo/Chinedu Asadu, File)

FILE - Then-recently freed students of the LEA Primary and Secondary School Kuriga gather upon arrival to reunite with their parents after more than two weeks in captivity, in Kuriga, Nigeria, Thursday, March 28, 2024. Their experience represents a worrying new development in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country where the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region. (AP Photo/Olalekan Richard, File)

FILE - Chibok schoolgirls, freed some years ago from Nigeria extremist captivity, are seen in Abuja, Nigeria. Monday May 8, 2017. Their experience represents a worrying new development in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country where the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region. (AP Photo/Sunday Alamba, File)

FILE - Chibok schoolgirls freed from Boko Haram captivity are seen in Abuja, Nigeria, Sunday May 7, 2017. Seven years after Boko Haram extremists abducted more than 270 schoolgirls in northeast Nigeria, two of the more than 100 still being held by the rebels returned this month, renewing the hope of parents who have all but given up on the long wait for the return of their children. Some of the affected parents said they remain hopeful that they will reunite with their children in Borno State, where the Boko Haram insurgency has lasted for more than a decade. (AP Photo/ Olamikan Gbemiga, File)

FILE- Jummai Mutah, left, and Amina Ali, Chibok schoolgirls who were kidnapped in 2014 by Islamic extremists and later released, attend a 10th anniversary event of the abduction in Lagos, Nigeria, Thursday, April 4, 2024. Their experience represents a worrying new development in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country where the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region. (AP Photo/Mansur Ibrahim, File )

Mary Peter, mother of Jennifer Peter, who was kidnapped with others in her school by gunmen in March 2021, listens to a question during an interview with The Associated Press in Kaduna, Nigeria, Tuesday , March, 26, 2024. The gunmen who kidnapped Jennifer Peter and dozens of her peers from school in March 2021 returned months later to attack another school in her state in northwestern Nigeria. The second time, they seized over 100 children including Jennifer's 10-year-old cousin, Treasure, who was held captive for more than two years. (AP Photo/Chinedu Asadu)

Mary Peter, mother of Jennifer Peter, who was kidnapped with others in her school by gunmen in March 2021, sobs during an interview with The Associated Press in Kaduna, Nigeria, Tuesday, March, 26, 2024. The gunmen who kidnapped Jennifer Peter and dozens of her peers from school in March 2021 returned months later to attack another school in her state in northwestern Nigeria. The second time, they seized over 100 children including Jennifer's 10-year-old cousin, Treasure, who was held captive for more than two years. (AP Photo/Chinedu Asadu)

Jennifer Peter, who was kidnapped with others in her school by gunmen in March 2021, play with her mobile phone in Kaduna, Nigeria, Tuesday , March, 26, 2024. The gunmen who kidnapped Jennifer Peter and dozens of her peers from school in March 2021 returned months later to attack another school in her state in northwestern Nigeria. The second time, they seized over 100 children including Jennifer's 10-year-old cousin, Treasure, who was held captive for more than two years. (AP Photo/Chinedu Asadu)

Jennifer Peter, who was kidnapped with others in her school by gunmen in March 2021, speaks during an interview in Kaduna, Nigeria, Tuesday, March, 26, 2024. The gunmen who kidnapped Jennifer Peter and dozens of her peers from school in March 2021 returned months later to attack another school in her state in northwestern Nigeria. The second time, they seized over 100 children including Jennifer's 10-year-old cousin, Treasure, who was held captive for more than two years. (AP Photo/Chinedu Asadu)

Treasure's ordeal is part of a worrying new development in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country where the mass abduction of 276 Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear —with nearly 100 of the girls still in captivity. Since the Chibok abductions, at least 1,500 students have been kidnapped, as armed groups increasingly find in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly policed northwestern region.

The Associated Press spoke with five families whose children have been taken hostage in recent years and witnessed a pattern of trauma and struggle with education among the children. Parents are becoming more reluctant to send their children to school in parts of northern Nigeria, worsening the education crisis in a country of over 200 million where at least 10 million children are out of school — one of the world's highest rates.

The AP could not speak with Treasure, who is undergoing therapy after escaping captivity in November. His relatives, however, were interviewed at their home in Kaduna state, including Jennifer, his cousin, who was also kidnapped when her boarding school was attacked in March 2021.

“I have not recovered, my family has not recovered (and) Treasure barely talks about it,” said Jennifer, 26, as her mother sobbed beside her. “I don’t think life will ever be the same after all the experience,” she added.

Unlike the Islamic extremists that staged the Chibok kidnappings, the deadly criminal gangs terrorizing villages in northwestern Nigeria are mostly former herdsmen who were in conflict with farming host communities, according to authorities. Aided by arms smuggled through Nigeria’s porous borders, they operate with no centralized leadership structure and launch attacks driven mostly by economic motive.

Some analysts see school kidnappings as a symptom of Nigeria’s worsening security crisis.

According to Nigerian research firm SBM Intelligence, nearly 2,000 people have been abducted in exchange for ransoms this year. However, armed gangs find the kidnapping of schoolchildren a “more lucrative way of getting attention and collecting bigger ransoms,” said Rev. John Hayab, a former chairman of the local Christian association in Kaduna who has often helped to secure the release of abducted schoolchildren like Treasure.

The security lapses that resulted in the Chibok kidnappings 10 years ago remain in place in many schools, according to a recent survey by the United Nations children’s agency’s Nigeria office, which found that only 43% of minimum safety standards such as perimeter fencing and guards are met in over 6,000 surveyed schools.

Bola Tinubu, who was elected president in March 2023, had promised to end the kidnappings while on the campaign trail. Nearly a year into his tenure there is still “a lack of will and urgency and a failure to realize the gravity of the situation, or to respond to it,” said Nnamdi Obasi, senior adviser for Nigeria at the International Crisis Group.

“There is no focused attention or commitment of resources on this emergency,” he added.

Treasure was the youngest of more than 100 children seized from the Bethel Baptist High School in the Chikun area of Kaduna in 2021. After receiving ransoms and freeing the other children in batches, his captors vowed to keep him, said Rev. Hayab.

That didn't stop his family from clinging to hope that he would one day return home alive. His grandmother, Mary Peter, remembers the night he returned home, agitated and hungry.

"He told us he was hungry and wanted to eat,” she said of Treasure's first words that night after two years and three months in captivity.

“Treasure went through hell,” said Rev. Hayab with the Christian association. “We need to work hard to get him out of ... what he saw, whatever he experienced."

Nigerian lawmakers in 2022 outlawed ransom payments, but desperate families continue to pay, knowing kidnappers can be ruthless, sometimes killing their victims when their relatives delay ransom payments often delivered in cash at designated locations.

And sometimes, even paying a ransom does not guarantee freedom. Some victims have accused security forces of not doing anything to arrest the kidnappers even after providing information about their calls and where their hostages were held.

Such was the experience of Treasure's uncle Emmanuel Audu, who was seized and chained to a tree for more than a week after he had gone to deliver the ransom demanded for his nephew to be freed.

Audu and other hostages were held in Kaduna’s notorious Davin Rugu forest. Once a bustling forest reserve that was home to wild animals and tourists, it is now one of the bandit enclaves in the ungoverned and vast woodlands tucked between mountainous terrains and stretching across thousands of kilometers as they connect states in the troubled region.

“The whole forest is occupied by kidnappers and terrorists,” Audu said as he talked about his time in captivity. His account was corroborated by several other kidnap victims and analysts.

Some of his captors in the forest were boys as young as Treasure, a hint of what his nephew could have become, and a sign that a new generation of kidnappers is already emerging.

"They beat us mercilessly. When you faint, they will flog you till you wake up,” he said, raising his hand to show the scars that reminded him of life in captivity.

No one in the Peter family recovered after their experience with kidnapping.

Jennifer says she rarely sleeps well even though it's been almost three years since she was freed by her captors. Her mother, a food trader, is finding it hard to raise capital again for her business after using most of her savings and assets inherited from her late husband to pay for ransoms.

Therapy is so costly, that the church had to sponsor that of Treasure while other members of the family are left to endure and hope they eventually get over their experiences.

“Sometimes, when I think about what happened, I wish I did not go to school,” said Jennifer with a rueful grin. “I just feel sorry for the children that are still in boarding school because it is not safe. They are the main target.”

The Associated Press receives financial support for global health and development coverage in Africa from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Trust. The AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Find more of AP's Africa coverage at https://apnews.com/hub/africa

FILE - A group of men identified by Nigerian police as Boko Haram extremist fighters and leaders are shown to the media, in Maiduguri, Nigeria, Wednesday, July 18, 2018. His experience represents a worrying new development in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country where the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region.(AP Photo/Jossy Ola, File)

FILE- People gather to welcome then-recently freed students of the LEA Primary and Secondary School Kuriga upon arrival to reunite with there parents in Kuriga, Nigeria, Thursday, March 28, 2024. Their experience represents a worrying new development in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country where the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region. (AP Photo/Olalekan Richard, File)

FILE - Security walk past the burned government secondary school Chibok where gunmen abducted more than 200 students in Chibok, Nigeria, Monday, April, 21. 2014. In Nigeria, Africa's most populous country, the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region. (AP Photo/ Haruna Umar, File)

FILE - Freed students of the LEA Primary and Secondary School Kuriga sit upon their arrival at the state government house in Kaduna, Nigeria, Monday, March 25, 2024. Their experience represents a worrying new development in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country where the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region. (AP Photo/Habila Darofai, File)

FILE- Then-recently freed Chibok schoolgirls sit with their children at the Army Maimalari Cantonment in Maiduguri, Nigeria, Thursday, May 4, 2023. Their experience represents a worrying new development in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country where the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region. (AP Photo/Jossy Ola, File)

FILE - Some of the escaped kidnapped girls of the government secondary school Chibok arrive for a meeting with Borno state governor, in Maiduguri, Nigeria, Monday June, 2. 2014. Their experience represents a worrying new development in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country where the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region. (AP Photo/Jossy Ola, File)

FILE - Freed students of the LEA Primary and Secondary School Kuriga leave a van upon arrival at the government house in Kaduna, Nigeria, Monday, March 25, 2024. Their experience represents a worrying new development in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country where the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region. (AP Photo/Chinedu Asadu, File)

FILE - Then-recently freed students of the LEA Primary and Secondary School Kuriga gather upon arrival to reunite with their parents after more than two weeks in captivity, in Kuriga, Nigeria, Thursday, March 28, 2024. Their experience represents a worrying new development in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country where the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region. (AP Photo/Olalekan Richard, File)

FILE - Chibok schoolgirls, freed some years ago from Nigeria extremist captivity, are seen in Abuja, Nigeria. Monday May 8, 2017. Their experience represents a worrying new development in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country where the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region. (AP Photo/Sunday Alamba, File)

FILE - Chibok schoolgirls freed from Boko Haram captivity are seen in Abuja, Nigeria, Sunday May 7, 2017. Seven years after Boko Haram extremists abducted more than 270 schoolgirls in northeast Nigeria, two of the more than 100 still being held by the rebels returned this month, renewing the hope of parents who have all but given up on the long wait for the return of their children. Some of the affected parents said they remain hopeful that they will reunite with their children in Borno State, where the Boko Haram insurgency has lasted for more than a decade. (AP Photo/ Olamikan Gbemiga, File)

FILE- Jummai Mutah, left, and Amina Ali, Chibok schoolgirls who were kidnapped in 2014 by Islamic extremists and later released, attend a 10th anniversary event of the abduction in Lagos, Nigeria, Thursday, April 4, 2024. Their experience represents a worrying new development in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country where the mass abduction of Chibok schoolgirls a decade ago marked a new era of fear even as nearly 100 of the girls remain in captivity. An array of armed groups now focus on abducting schoolchildren, seeing in them a lucrative way to fund other crimes and control villages in the nation's mineral-rich but poorly-policed northwestern region. (AP Photo/Mansur Ibrahim, File )

Mary Peter, mother of Jennifer Peter, who was kidnapped with others in her school by gunmen in March 2021, listens to a question during an interview with The Associated Press in Kaduna, Nigeria, Tuesday , March, 26, 2024. The gunmen who kidnapped Jennifer Peter and dozens of her peers from school in March 2021 returned months later to attack another school in her state in northwestern Nigeria. The second time, they seized over 100 children including Jennifer's 10-year-old cousin, Treasure, who was held captive for more than two years. (AP Photo/Chinedu Asadu)

Mary Peter, mother of Jennifer Peter, who was kidnapped with others in her school by gunmen in March 2021, sobs during an interview with The Associated Press in Kaduna, Nigeria, Tuesday, March, 26, 2024. The gunmen who kidnapped Jennifer Peter and dozens of her peers from school in March 2021 returned months later to attack another school in her state in northwestern Nigeria. The second time, they seized over 100 children including Jennifer's 10-year-old cousin, Treasure, who was held captive for more than two years. (AP Photo/Chinedu Asadu)

Jennifer Peter, who was kidnapped with others in her school by gunmen in March 2021, play with her mobile phone in Kaduna, Nigeria, Tuesday , March, 26, 2024. The gunmen who kidnapped Jennifer Peter and dozens of her peers from school in March 2021 returned months later to attack another school in her state in northwestern Nigeria. The second time, they seized over 100 children including Jennifer's 10-year-old cousin, Treasure, who was held captive for more than two years. (AP Photo/Chinedu Asadu)

Jennifer Peter, who was kidnapped with others in her school by gunmen in March 2021, speaks during an interview in Kaduna, Nigeria, Tuesday, March, 26, 2024. The gunmen who kidnapped Jennifer Peter and dozens of her peers from school in March 2021 returned months later to attack another school in her state in northwestern Nigeria. The second time, they seized over 100 children including Jennifer's 10-year-old cousin, Treasure, who was held captive for more than two years. (AP Photo/Chinedu Asadu)

JERUSALEM (AP) — The chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court said Monday he is seeking arrest warrants for leaders of Israel and Hamas, including Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, over actions taken during their seven-month war.

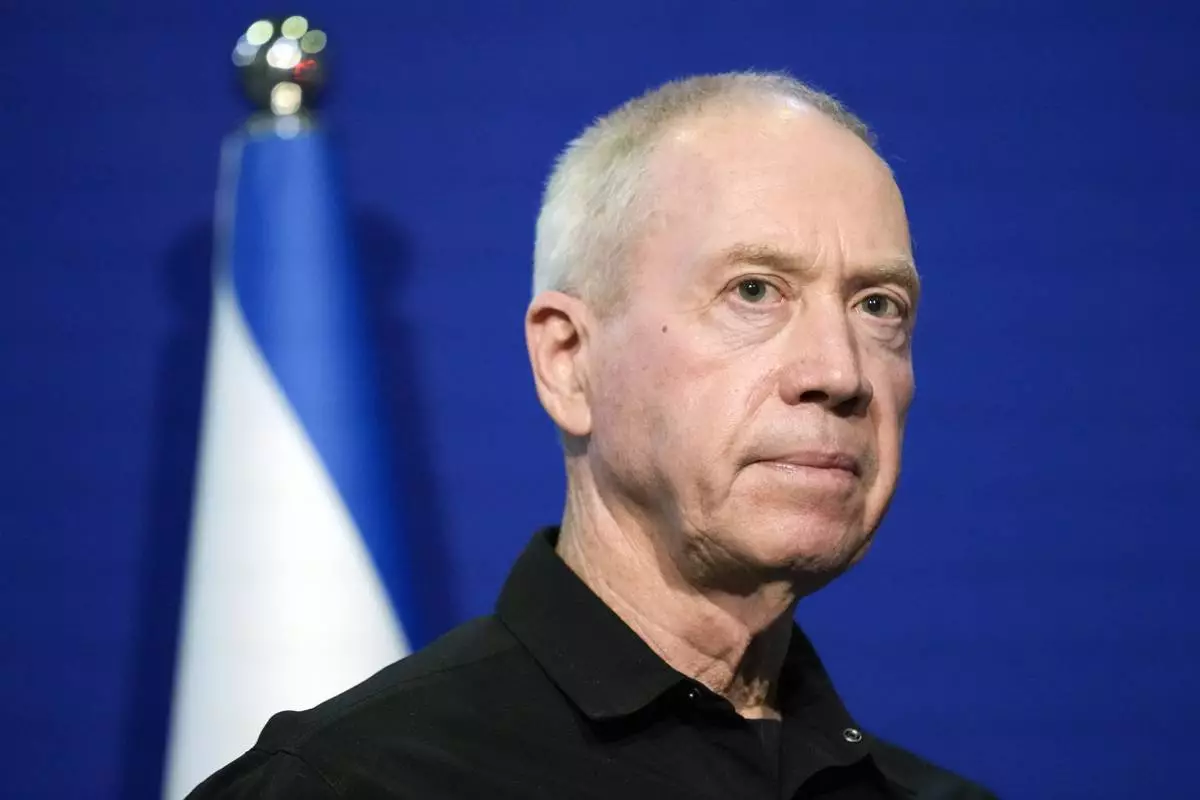

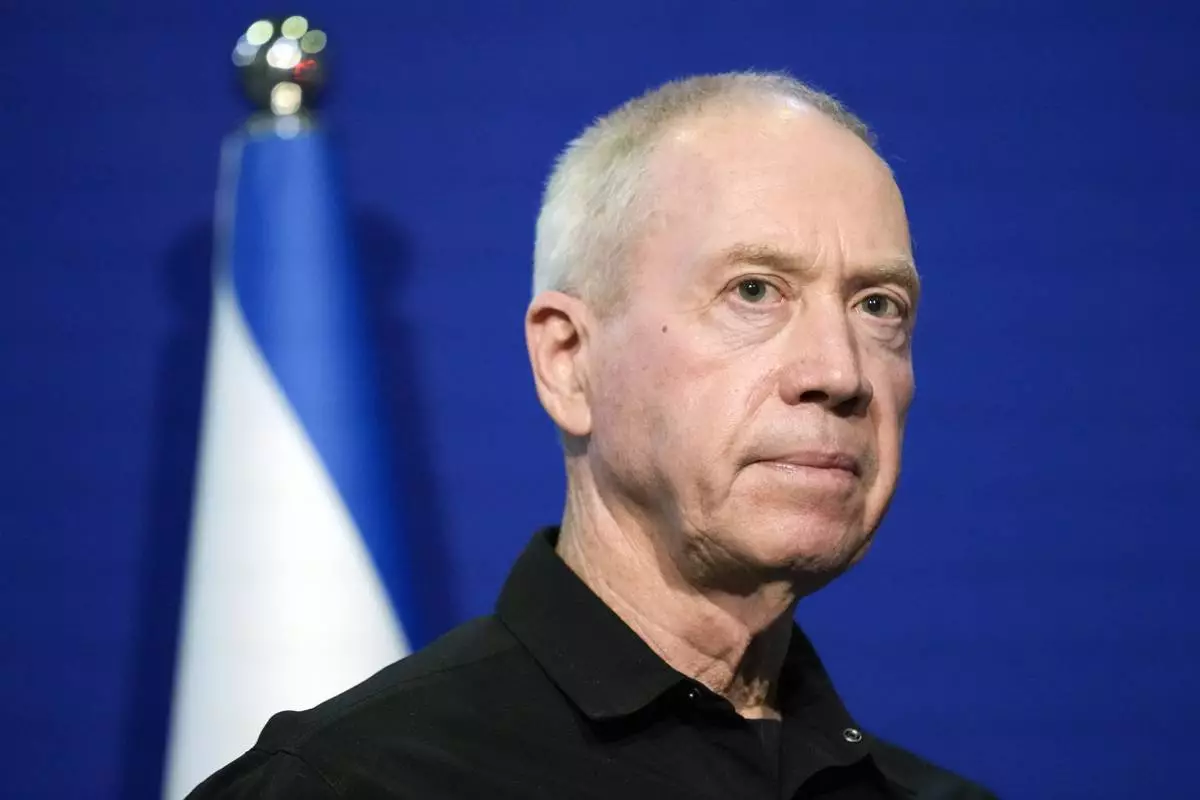

While Netanyahu and his defense minister, Yoav Gallant, do not face imminent arrest, the announcement by ICC Chief Prosecutor Karim Khan was a symbolic blow that deepened Israel’s isolation over the war in Gaza.

Khan accused Netanyahu, Gallant, and three Hamas leaders — Yehia Sinwar, Mohammed Deif and Ismail Haniyeh — of war crimes and crimes against humanity in the Gaza Strip and Israel.

A panel of three judges will consider the prosecutor's evidence and determine whether to issue the arrest warrants and allow a case to proceed. The judges typically take two months to make such decisions.

Israel is not a member of the court, so even if the arrest warrants are issued, Netanyahu and Gallant do not face any immediate risk of prosecution. But Khan's announcement deepens Israel's isolation as it presses ahead in Gaza, and the threat of arrest could make it difficult for the Israeli leaders to travel abroad.

Israeli Foreign Minister Israel Katz said the chief prosecutor's decision against its leaders is “a historic disgrace that will be remembered forever.” He said he would work with world leaders to ensure that any such warrants are not enforced on Israel's leaders.

Hamas, which is considered a terrorist group by the West, also denounced the ICC prosecutor’s request to arrests its leaders.

Benny Gantz, a former military chief and member of Israel’s War Cabinet with Netanyahu and Gallant, harshly criticized Khan’s announcement, saying Israel fights with “one of the strictest” moral codes, respects international law and has a robust judiciary capable of investigating itself.

“The State of Israel is waging one of the just wars fought in modern history following a reprehensible massacre perpetrated by terrorist Hamas on the 7th of October,” he said.

Still, Netanyahu has come under heavy pressure at home to end the war sooner than later. Thousands of Israelis have joined weekly demonstrations calling on the government to reach a deal to bring home Israeli hostages in Hamas captivity.

In recent days, the two other members of his war Cabinet, Gallant and Benny Gantz, have threatened to resign if Netanyahu does not spell out a clear postwar vision for Gaza.

But on Monday, Netanyahu received wall-to-wall support as politicians across the spectrum condemned the ICC prosecutor’s move, including opposition leader Yair Lapid.

In a statement, Hamas accused the prosecutor of trying to “equate the victim with the executioner.” It said it has the right to resist Israeli occupation, including “armed resistance.”

It also criticized the court for seeking the arrests of only two Israeli leaders and said it should seek warrants for other Israeli leaders.

Both Sinwar and Deif are believed to be hiding in Gaza as Israel tries to hunt them down. But Haniyeh, the supreme leader of the Islamic militant group, is based in Qatar and frequently travels across the region.

The latest war between Israel and Hamas began on Oct. 7, when militants from Gaza crossed into Israel and killed some 1,200 people, mostly civilians, and took 250 others hostage.

Since then, Israel has waged a brutal campaign to dismantle Hamas in Gaza. More than 35,000 Palestinians have been killed in the fighting, at least half of them women and children, according to the latest estimates by Gaza health officials.

The war has triggered a humanitarian crisis in Gaza, displacing roughly 80% of the population and leaving hundreds of thousands of people on the brink of starvation, according to U.N. officials.

Speaking of the Israeli actions, Khan said in a statement that “the effects of the use of starvation as a method of warfare, together with other attacks and collective punishment against the civilian population of Gaza are acute, visible and widely known. ... They include malnutrition, dehydration, profound suffering and an increasing number of deaths among the Palestinian population, including babies, other children, and women.”

The United Nations and other aid agencies have repeatedly accused Israel of hindering aid deliveries throughout the war. Israel denies this, saying there are no restrictions on aid entering Gaza and accusing the U.N. of failing to distribute aid.

The U.N. says aid workers have repeatedly come under Israeli fire, and also says ongoing fighting and a security vacuum have impeded deliveries.

Of the Hamas actions on Oct. 7, Khan, who visited the region in December, said that he saw for himself "the devastating scenes of these attacks and the profound impact of the unconscionable crimes charged in the applications filed today. Speaking with survivors, I heard how the love within a family, the deepest bonds between a parent and a child, were contorted to inflict unfathomable pain through calculated cruelty and extreme callousness. These acts demand accountability.”

After a brief period of international support, Israel has faced increasing criticism as the war has dragged on and the death toll has climbed.

Israel is also facing a South African case in the International Court of Justice, the U.N.'s top court, accusing Israel of genocide. Israel denies those charges.

The ICC was established in 2002 as the permanent court of last resort to prosecute individuals responsible for the world’s most heinous atrocities — war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide and the crime of aggression.

The U.N. General Assembly endorsed the ICC, but the court is independent.

Dozens of countries don’t accept the court’s jurisdiction over war crimes, genocide and other crimes. They include Israel, the United States, Russia and China.

The ICC becomes involved when nations are unable or unwilling to prosecute crimes on their territory. Israel argues it has a functioning court system.

The ICC accepted “The State of Palestine” as a member in 2015, a year after the Palestinians accepted the court’s jurisdiction.

The court’s chief prosecutor at the time announced in 2021 she was opening an investigation into possible crimes on Palestinian territory. Israel often levies accusations of bias at U.N. and international bodies, and Netanyahu condemned the decision as hypocritical and antisemitic.

In 2020, then U.S. President Donald Trump authorized economic and travel sanctions on the ICC prosecutor and another senior prosecutor. The ICC staff were looking into U.S. and allies’ troops for possible war crimes in Afghanistan.

U.S. President Joe Biden lifted the sanctions in 2021.

Last year, the court issued a warrant for Russian President Vladimir Putin on charges of responsibility for the abductions of children from Ukraine. Russia responded by issuing its own arrest warrants for Khan and ICC judges.

Other high-profile leaders charged by the court include ousted Sudanese strongman Omar al-Bashir on allegations that include genocide in his country’s Darfur region. Former Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi was captured and killed by rebels shortly after the ICC issued a warrant for his arrest on charges linked to the brutal suppression of anti-government protests in 2011.

Molly Quell in Delft, Netherlands, and Mike Corder in Ede, Netherlands, contributed.

Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant pauses while making a brief statement to the media with U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, not pictured, at The Kirya, Israel's Ministry of Defense, Monday, Oct. 16, 2023, in Tel Aviv. The chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court said Monday, May 20, 2024, he is seeking arrest warrants for Israeli and Hamas leaders, including Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, in connection with their actions during the seven-month war between Israel and Hamas. Netanyahu, his defense minister Gallant, and three Hamas leaders, are believed to be responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity in the Gaza Strip and Israel. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin, Pool, File)

Hamas chief Ismail Haniyeh speaks during a press briefing after his meeting with Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amirabdollahian in Tehran, Iran, Tuesday, March 26, 2024. The chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court said Monday he is seeking arrest warrants for Israeli and Hamas leaders, including Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, in connection with their actions during the seven-month war between Israel and Hamas. Haniyeh is one of the three Hamas leaders believed to be responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity in the Gaza Strip and Israel. (AP Photo/Vahid Salemi, File)

Yehia Sinwar, head of Hamas in Gaza, greets his supporters during a meeting with leaders of Palestinian factions at his office in Gaza City, Wednesday, April 13, 2022. The chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court said Monday he is seeking arrest warrants for Israeli and Hamas leaders, including Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, in connection with their actions during the seven-month war between Israel and Hamas. Yehia Sinwar is one of the three Hamas leaders believed to be responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity in the Gaza Strip and Israel. (AP Photo/Adel Hana)

FILE - Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu chairs a cabinet meeting at the Kirya military base, which houses the Israeli Ministry of Defense, in Tel Aviv, Israel, on Dec. 24, 2023. The chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court said Monday, May 20, 2024 he is seeking arrest warrants for Israeli and Hamas leaders, including Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, in connection with their actions during the seven-month war between Israel and Hamas. (AP Photo/Ohad Zwigenberg, Pool, File)