ASTANA, Kazakhstan (AP) — If the choice was death or a bullet to the leg, Yevgeny would take the bullet. A decorated hero of Russia’s war in Ukraine, Yevgeny told his friend and fellow soldier to please aim carefully and avoid bone. The tourniquets were ready.

The pain that followed was the price Yevgeny paid for a new chance at life. Like thousands of other Russian soldiers, he deserted.

“I joke that I gave birth to myself,” he said, declining to give his full name for fear of retribution. “When a woman gives birth to a child, she experiences very intense pain and gives new life. I gave myself life after going through very intense pain.”

Yevgeny made it out of the trenches. But the new life he found is not what he had hoped for.

The Associated Press spoke with five officers and one soldier who deserted the Russian military. All have criminal cases against them in Russia, where they face 10 years or more in prison. Each is waiting for a welcome from the West that has never arrived. Instead, all but one live in hiding.

For Western nations grappling with Russia’s vast and growing diaspora, Russian soldiers present particular concern: Are they spies? War criminals? Or heroes?

“I did the right thing,” said another deserter who goes by the nickname Sparrow, who is living in hiding in Kazakhstan while he waits for his asylum applications to be processed. After being forcibly conscripted, he ran away from his barracks because he didn't want to kill anyone. “I’d rather sit here and suffer and look for something than go there and kill a human being because of some unclear war, which is 100 percent Russia’s fault. I don’t regret it.”

Asylum claims from Russian citizens have surged since the full-scale invasion, but few are winning protection. Policymakers remain divided over whether to consider Russians in exile as potential assets or risks to national security.

Andrius Kubilius, a former prime minister of Lithuania now serving in the European Parliament, argues that cultivating Russians who oppose Vladimir Putin is in the strategic self-interest of the West. Fewer Russian soldiers at the front, he added, means a weaker army.

“Not to believe in Russian democracy is a mistake,” Kubilius said. “To say that all Russians are guilty is a mistake.”

Independent Russian media outlet Mediazona has documented more than 7,300 cases in Russian courts against AWOL soldiers since September 2022; cases of desertion, the harshest charge, leapt sixfold last year.

Record numbers of people seeking to desert — more than 500 in the first two months of this year — are contacting Idite Lesom, or “Get Lost,” a group run by Russian activists in the Republic of Georgia. Last spring, just 3% of requests for help came from soldiers seeking to leave; in January, more than a third did, according to the group’s head, Grigory Sverdlin.

Overall, Sverdlin’s group says it has supported more than 26,000 Russians seeking to avoid military service and helped more than 520 active-duty soldiers and officers flee — a drop in the bucket compared with Russia’s overall troop strength, but an indicator of morale in a country that has made it a crime to oppose the war.

“Obviously, Russian propaganda is trying to sell us a story that all Russia supports Putin and his war,” Sverdlin said. "But that’s not true.”

The question now is, where can they go?

Farhad Ziganshin, an officer who deserted shortly after Putin's September 2022 mobilization decree, was detained in Kazakhstan while trying to board a flight to Armenia because local authorities found his name on a Russian wanted list.

“It’s not safe to stay in Kazakhstan,” Ziganshin said. “I just try to lead a normal life, without violating the laws of Kazakhstan, without being too visible, without appearing anywhere. We have a proverb: Be quieter than water and lower than grass.”

He's still waiting on his asylum applications.

German officials have said that Russians fleeing military service can seek protection, and a French court last summer ruled that Russians who refuse to fight can claim refugee status. In practice, however, it’s proven difficult for deserters, most of whom have passports that only allow travel within a handful of former Soviet states, to get asylum, lawyers, activists and deserters say.

Fewer than 300 Russians got refugee status in the U.S. in fiscal year 2022. And less than 10% of the 5,246 people whose applications were processed last year got some sort of protection from German authorities.

But Russians continue to flee. Customs and Border Patrol officials encountered more than 57,000 Russians at U.S. borders in fiscal year 2023, up from around 13,000 in fiscal year 2021. Affirmative asylum requests nearly quadrupled, to almost 9,000, in the year ending September 2022, the latest data available.

In France, asylum requests rose more than 50% between 2022 and 2023, to a total of around 3,400 people, according to the French office that handles the requests. And last year, Germany got 7,663 first-time asylum applications from Russian citizens, up from 2,851 in 2022, Germany’s Interior Ministry told AP in an email. None of the data specifies how many were soldiers.

Another Russian officer, nicknamed Sportsmaster, made a video diary of his escape. As he was about to leave Russia, he did what he could to make a grand gesture to demonstrate his opposition to the war.

“They wanted to force me to go fight against the free people of Ukraine,” he said to his camera. “Putin wanted me to be in a bag, but it’s his uniform that will be in a bag.”

He shoved his military uniforms in two black trash bags and threw them in a dumpster.

“The worst thing that could have happened has happened,” he said after crossing out of Russia with the remnants of his former life stuffed in one small backpack. “Now only good things are coming.”

Sportsmaster is an optimist. In fact, deserters have been seized by Russian forces in Armenia, deported from Kazakhstan and turned up dead, riddled with bullets, in Spain.

“There is no mechanism for Russians who do not want to fight, deserters, to get to a safe place,” Yevgeny said. He urges Western policymakers to reconsider. “After all, it’s much cheaper economically to allow a person into your country — a healthy young man who can work — than to supply Ukraine with weapons.”

AP journalists Geir Moulson in Berlin, Lori Hinnant in Paris and Rebecca Santana in Washington contributed to this report.

In a joint production, The Associated Press and Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting broadcast the story of an underground network of Russian anti-war activists helping soldiers abandon Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine.

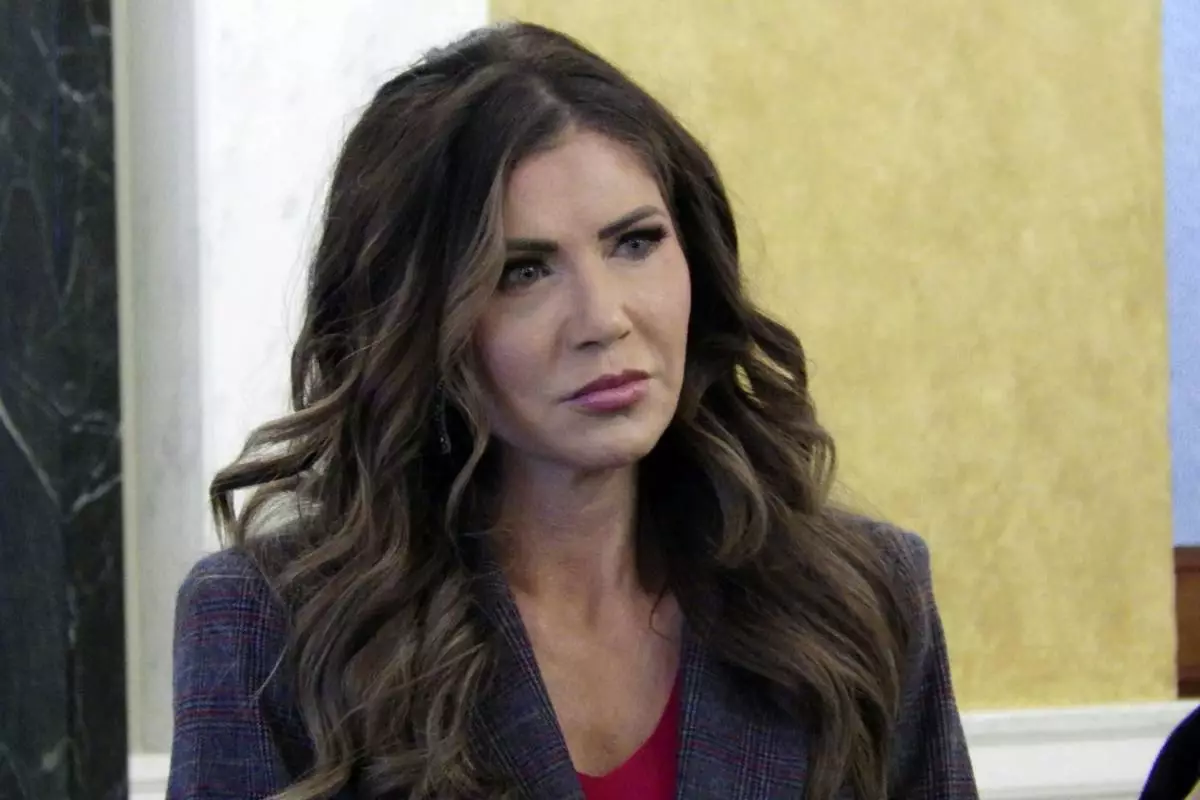

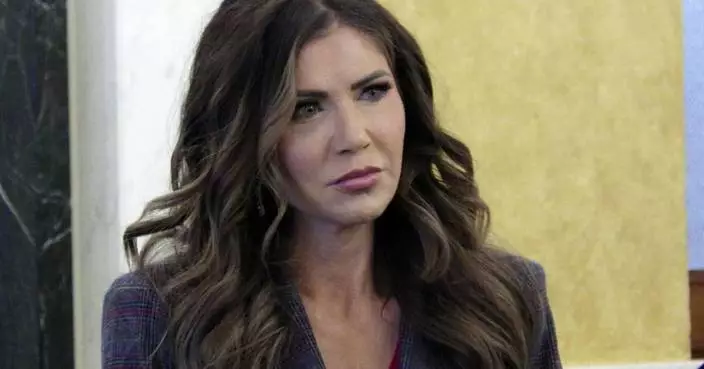

A Russian officer who goes by the nickname Sportsmaster speaks with reporters at his apartment in Astana, Kazakhstan, in late 2023. He faces criminal charges in Russia for refusing to go to war in Ukraine. "I immediately decided that I would not support it in any way, not even lift my little finger to support what had begun," he said. "I understood that this was a point of no return that would change the lives of the entire country, including mine." (AP Photo)

Farhad Ziganshin, a Russian officer who deserted in 2022, sits at a table after lunch at his temporary apartment in Astana, Kazakhstan, in late 2023. "I realized that I didn't want to serve in this kind of Russian army that destroys cities, kills civilians, and forcibly appropriates foreign land and territory," he said. (AP Photo)

A Russian soldier who goes by the nickname Sparrow sits at his kitchen table in his apartment in Astana, Kazakhstan, in late 2023. After being forcibly conscripted, he ran away from his barracks because he didn't want to kill anyone. "I don't want anything in life. I have no interest in my own affairs," he said. "I just sit all day on the Internet, on YouTube, and read news, news, news of what's going on in Ukraine, and that's it." (AP Photo)

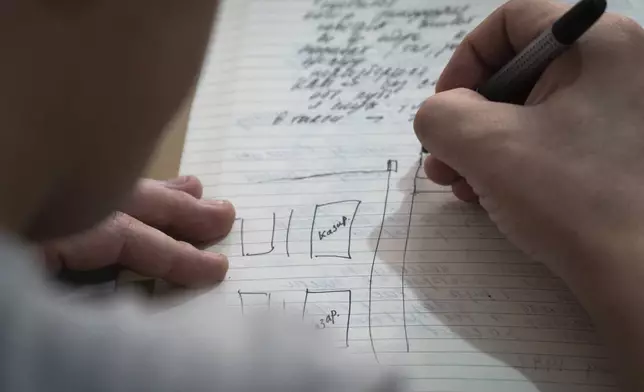

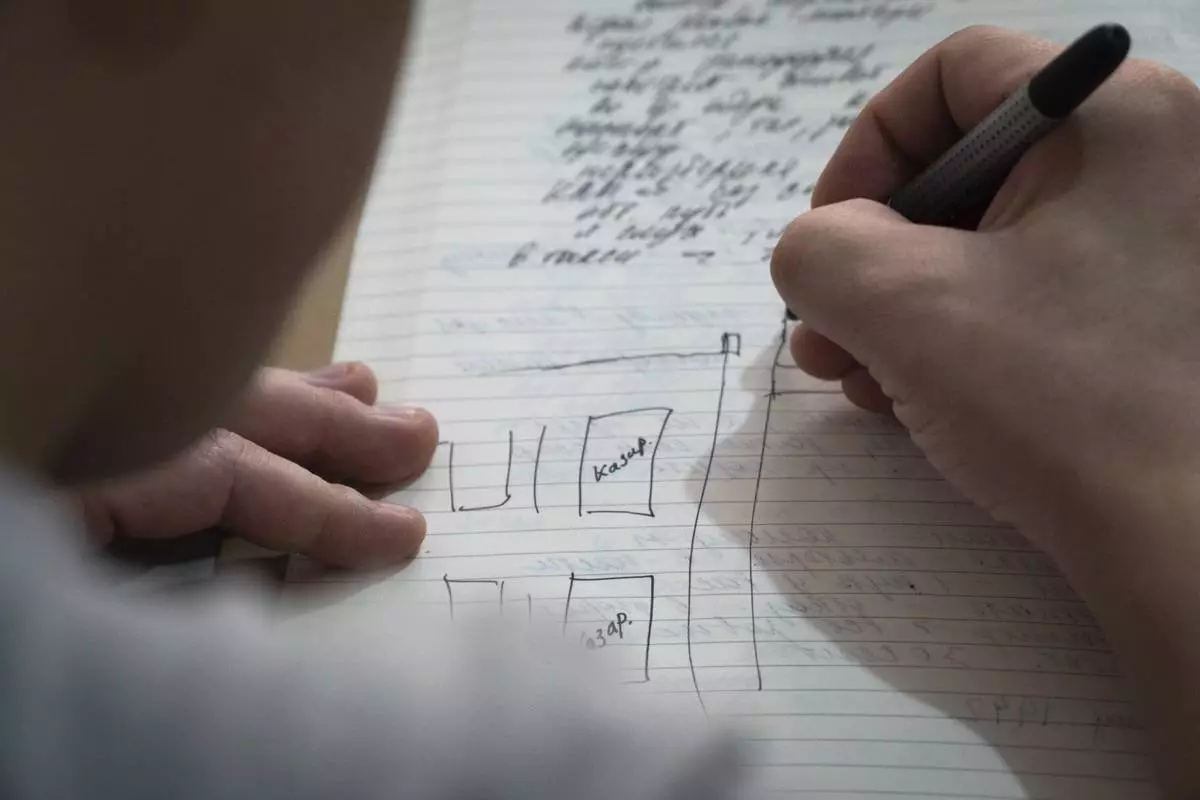

A Russian soldier in Astana, Kazakhstan who goes by the nickname Sparrow sketches the route he took to escape his military barracks in Russia in 2022, at his apartment in Astana, Kazakhstan, in late 2023. After being forcibly conscripted, he deserted because he didn't want to kill anyone. "I did the right thing," he said. "I'd rather sit here and suffer and look for something than go there and kill a human being because of some unclear war, which is 100 percent Russia's fault." (AP Photo)

A Russian soldier who goes by the nickname Sparrow prepares tea at his apartment in Astana, Kazakhstan, in late 2023. After being forcibly conscripted, he ran away from his barracks because he didn't want to kill anyone. Now he faces criminal charges in Russia. "I don't want anything in life. I have no interest in my own affairs," he said. "I just sit all day on the Internet, on YouTube, and read news, news, news of what's going on in Ukraine, and that's it." (AP Photo)

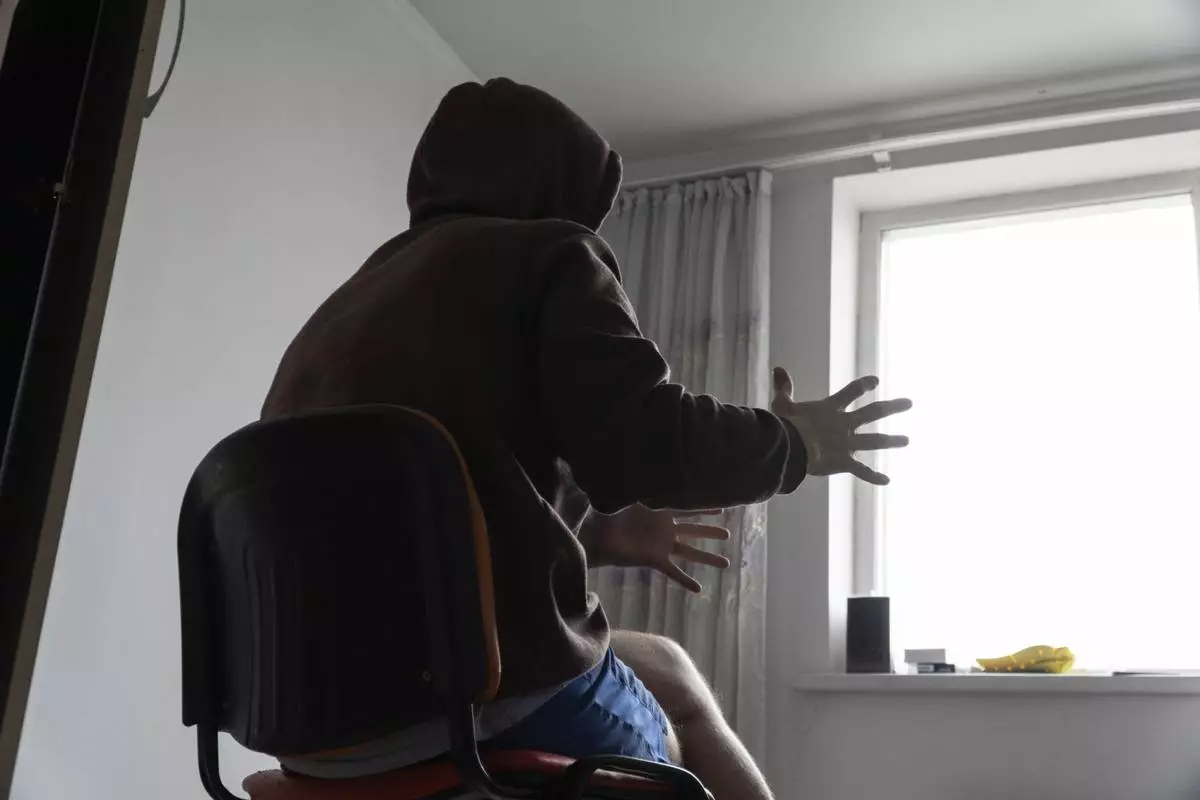

A Russian soldier who goes by the nickname Sparrow speaks with reporters at his apartment in Astana, Kazakhstan, in late 2023. After being forcibly conscripted, he ran away from his barracks because he didn't want to kill anyone. Now he faces criminal charges in Russia. "I did the right thing," he said. "I'd rather sit here and suffer and look for something than go there and kill a human being because of some unclear war, which is 100 percent Russia's fault." (AP Photo)

A Russian officer who goes by the nickname Sportsmaster speaks during an interview at his apartment in Astana, Kazakhstan, in late 2023. He faces criminal charges in Russia for refusing to go to war in Ukraine. "I immediately decided that I would not support it in any way, not even lift my little finger to support what had begun," he said. "I understood that this was a point of no return that would change the lives of the entire country, including mine." (AP Photo)

Farhad Ziganshin, a Russian officer who deserted in 2022, takes a walk after work in Astana, Kazakhstan, in late 2023. He dreams of starting a family but can't afford to take a woman out to the movies. "I can't fall in love with someone and have someone fall in love with me," he said. "So I just walk around and sing songs." (AP Photo)

Farhad Ziganshin, a Russian officer who deserted in 2022, speaks during an interview in Astana, Kazakhstan, in late 2023. He was detained for three days by Kazakh authorities when he tried to board a flight to Armenia. "It's not safe to stay in Kazakhstan," he said. (AP Photo)

Farhad Ziganshin, a Russian officer who deserted in 2022, stands at the door of his shared room in a temporary apartment in Astana, Kazakhstan, in late 2023. "Here I am living sleeping on coats, eating I don't know what. And without any money in my pocket. It's very depressing," he said. (AP Photo)

A Russian officer who goes by Yevgeny speaks during an interview at his apartment in Astana, Kazakhstan, in late 2023. He had a friend shoot him in the leg so he could get off the frontline in Ukraine. "There is no mechanism for Russians who do not want to fight, deserters, to get to a safe place," he said. (AP Photo)

Farhad Ziganshin, a Russian officer who deserted in 2022, pauses during an interview in Astana, Kazakhstan, in late 2023. He was detained for three days by Kazakh authorities when he tried to board a flight to Armenia. "It's not safe to stay in Kazakhstan," he said. (AP Photo)

This late 2023 photo shows downtown Astana, Kazakhstan, where some Russian soldiers who deserted the war in Ukraine live in hiding while they apply for asylum. Overall asylum claims from Russian citizens to the U.S., France and Germany have surged since Russia's full-scale invasion, but few are winning protection. Policymakers remain divided over whether to consider Russians in exile as potential assets or risks to national security. (AP Photo)

Thousands of Russian soldiers are fleeing the war in Ukraine but have nowhere to go

A Russian officer who goes by Yevgeny speaks during an interview at his apartment in Astana, Kazakhstan, in late 2023. He had a friend shoot him in the leg so he could get out off the frontline in Ukraine. "Many of my friends have died. And these were really good guys who didn't want to fight," he said. "But there was no way out for them." (AP Photo)

Thousands of Russian soldiers are fleeing the war in Ukraine but have nowhere to go