LONDON (AP) — A key plank in the British government’s plan to send some asylum-seekers on a one-way trip to Rwanda is expected to become law this week, but opponents plan new legal challenges that could keep deportation flights grounded.

A bill aimed at overcoming a U.K. Supreme Court block on sending migrants to Rwanda is due to pass Parliament after the government overcomes efforts to water it down in the House of Lords.

The Rwanda plan is key to Prime Minister Rishi Sunak ’s pledge to “stop the boats” bringing unauthorized migrants to the U.K., and Sunak has repeatedly said the long-delayed first flights will take off by June.

“This week Parliament has the opportunity to pass a bill that will save lives of those being exploited by people-smuggling gangs," Sunak's spokesman, Dave Pares, said Monday. “It is clear we cannot continue with the status quo … now is the time to change the equation.”

It has been two years since Britain and Rwanda signed a deal that would see migrants who cross the English Channel in small boats sent to the East African country, where they would remain permanently. The plan has been challenged in the courts, and no one has yet been sent to Rwanda under an agreement that has cost the U.K. at least 370 million pounds ($470 million).

In November, the U.K. Supreme Court ruled that the Rwanda plan was illegal because the nation wasn’t a safe destination for asylum-seekers. For decades, human rights groups and governments have documented alleged repression of dissent by Rwanda’s government both inside the country and abroad, as well as serious restrictions on internet freedom, assembly and expression.

In response to the ruling, Britain and Rwanda signed a treaty pledging to strengthen protections for migrants. Sunak’s government argues the treaty allows it to pass a law declaring Rwanda a safe destination.

The Safety of Rwanda Bill pronounces the country safe, making it harder for migrants to challenge deportation and allows the British government to ignore injunctions from the European Court of Human Rights that forbid removals.

Human rights groups, refugee charities, senior Church of England clerics and many legal experts have criticized the legislation. In February a parliamentary rights watchdog said the Rwanda plan is “ fundamentally incompatible ” with the U.K.’s human rights obligations.

The Safety of Rwanda Bill has been approved by the House of Commons, where Sunak’s Conservatives have a majority, only for members of Parliament’s unelected upper chamber, the House of Lords, to insert a series of amendments designed to water down the legislation and ensure it complies with international law.

The Commons rejected the changes last month, but the Lords refused to back down. The Commons is expected to send the unmodified bill back to the Lords late Monday in a process known as parliamentary ping pong. The back-and-forth could continue for several days, but ultimately, the elected Commons can overrule the unelected Lords.

“When a government devises and wants to implement a policy which is clear and precise in terms of its objectives, the Lords shouldn’t stand in its way,” Conservative lawmaker John Hayes told the BBC. “And I think in the end the Lords will give way on this because they recognize that balance.”

Once the bill becomes law, it could be weeks before any flights to Rwanda take off, as people chosen for deportation are likely to lodge legal appeals.

Just under 30,000 people arrived in Britain in small boats in 2023, and Sunak has made reducing that number a key issue ahead of an election due later this year. Some 6,000 people have made the journey so far in 2024, up from the same period last year, including 534 in 10 boats on Sunday.

The opposition Labour Party, which leads in opinion polls, opposes the Rwanda plan, arguing it won’t work, and says it would work with other European countries to tackle people-smuggling gangs.

The Times of London reported Monday that the U.K. government had approached other countries, including Costa Rica, Armenia, Ivory Coast and Botswana, about making similar deals if the Rwanda plan proves successful. The government said only that Britain is “continuing to work with a range of international partners to tackle global illegal migration challenges.”

Follow AP’s coverage of migration issues at https://apnews.com/hub/migration

Britain's Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, left, greets the President of Rwanda Paul Kagame on the doorstep of 10 Downing Street in London, Tuesday, April 9, 2024. (AP Photo/Alberto Pezzali)

BEIJING (AP) — The first scientist to publish a sequence of the COVID-19 virus in China said he was allowed back into his lab after he spent days locked outside, sitting in protest.

Zhang Yongzhen wrote in an online post on Wednesday, just past midnight, that the medical center that hosts his lab had “tentatively agreed” to allow him and his team to return and continue their research for the time being.

“Now, team members can enter and leave the laboratory freely,” Zhang wrote in a post on Weibo, a Chinese social media platform. He added that he is negotiating a plan to relocate the lab in a way that doesn’t disrupt his team’s work with the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center, which hosts Zhang’s lab.

Zhang and his team were suddenly told they had to leave their lab for renovations on Thursday, setting off the dispute, he said in an earlier post that was later deleted. On Sunday, Zhang began a sit-in protest outside his lab after he found he was locked out, a sign of continuing pressure on Chinese scientists conducting research on the coronavirus.

Zhang sat outside on flattened cardboard in drizzling rain, and members of his team unfurled a banner that read “Resume normal scientific research work," pictures posted online show. News of the protest spread widely on Chinese social media, putting pressure on local authorities.

In an online statement Monday, the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center said that Zhang’s lab was closed for “safety reasons” while being renovated. It added that it had provided Zhang’s team an alternative laboratory space.

But Zhang responded the same day his team wasn’t offered an alternative until after they were notified of their eviction, and the lab offered didn’t meet safety standards for conducting their research, leaving his team in limbo.

Zhang’s dispute with his host institution was the latest in a series of setbacks, demotions and ousters since the virologist published the sequence in January 2020 without state approval.

Beijing has sought to control information related to the virus since it first emerged. An Associated Press investigation found that the government froze domestic and international efforts to trace it from the first weeks of the outbreak. These days, labs are closed, collaborations shattered, foreign scientists forced out and some Chinese researchers barred from leaving the country.

Zhang’s ordeal started when he and his team decoded the virus on Jan. 5, 2020, and wrote an internal notice warning Chinese authorities of its potential to spread — but did not make the sequence public. The next day, Zhang’s lab was ordered to close temporarily by China’s top health official, and Zhang came under pressure from the authorities.

Foreign scientists soon learned that Zhang and other Chinese scientists had deciphered the virus and called on China to release the sequence. Zhang published it on Jan. 11, 2020, despite a lack of permission from Chinese health officials.

Sequencing a virus is key to the development of test kits, disease control measures and vaccinations. The virus eventually spread to every corner of the world, triggering a pandemic that disrupted lives and commerce, prompted widespread lockdowns and killed millions of people.

Zhang was awarded prizes overseas in recognition for his work. But health officials removed him from a post at the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention and barred him from collaborating with some of his former partners, hindering his research.

Still, Zhang retains support from some in the government. Though some of Zhang’s online posts were deleted, his sit-in protest was reported widely in China’s state-controlled media, indicating divisions within the Chinese government on how to deal with Zhang and his team.

“Thank you to my online followers and people from all walks of life for your concern and strong support over the past few days!” Zhang wrote in his post Wednesday.

Buildings in the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center stand near the entrance of the compound in Shanghai, China, Tuesday, April 30, 2024. Zhang Yongzhen, the first scientist to publish a sequence of the COVID-19 virus, staged a sit-in protest after authorities locked him out of his lab at the center. (AP Photo/Dake Kang)

Buildings in the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center stand near the entrance of the compound in Shanghai, China Tuesday, April 30, 2024. Zhang Yongzhen, the first scientist to publish a sequence of the COVID-19 virus, staged a sit-in protest after authorities locked him out of his lab at the center. (AP Photo/Dake Kang)

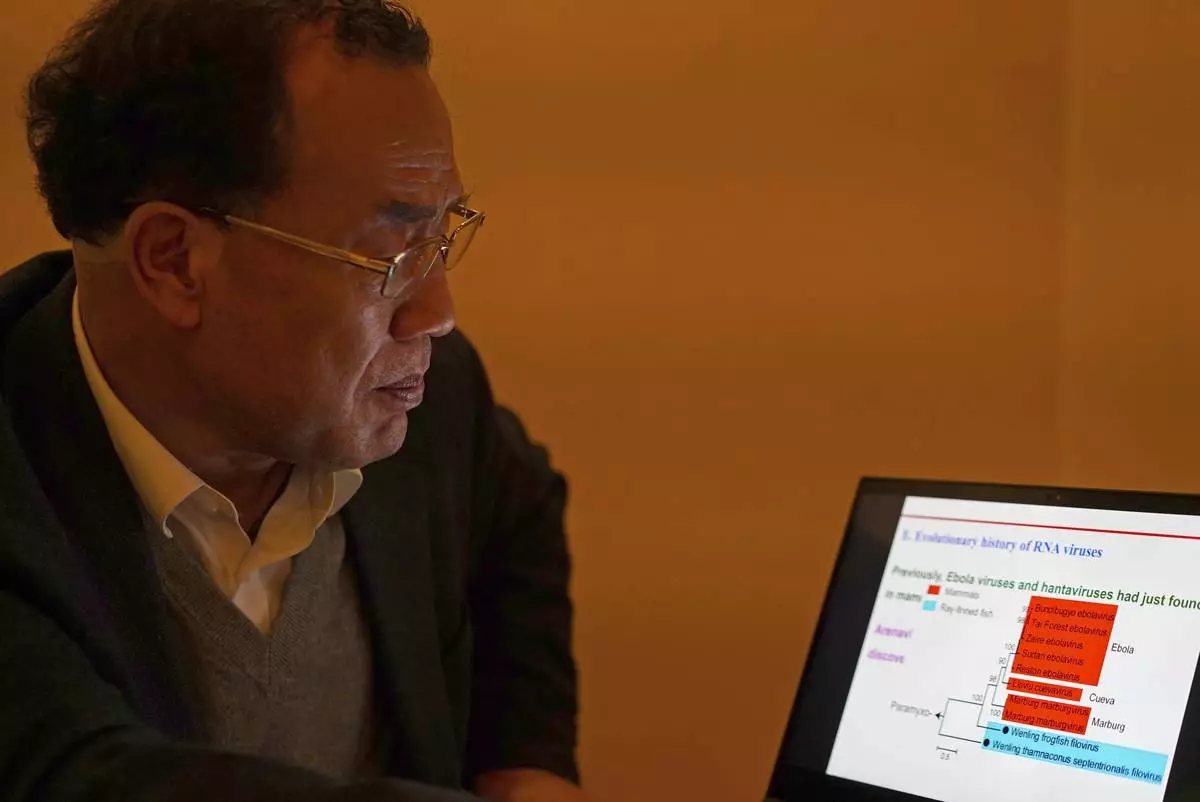

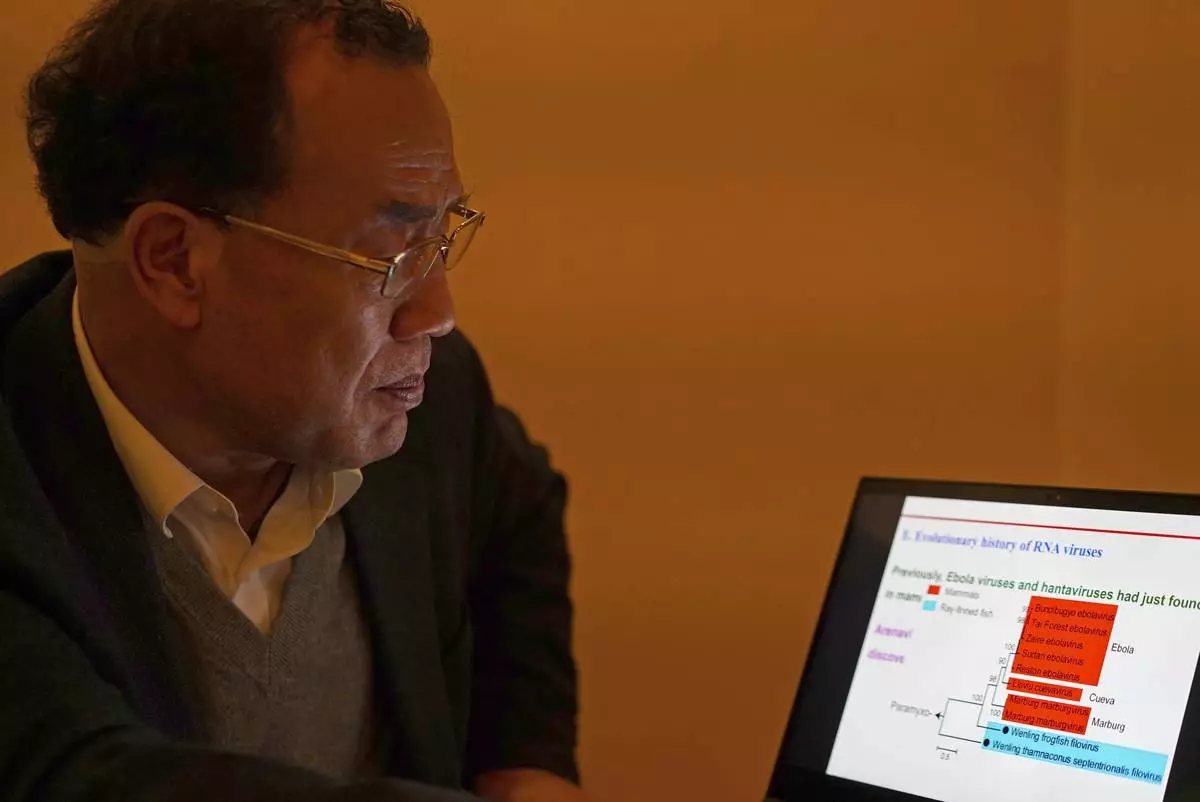

Zhang Yongzhen, the first scientist to publish a sequence of the COVID-19 virus, looks at a presentation on his laptop in a coffeeshop in Shanghai, China on Dec. 13, 2020. Zhang was staging a sit-in protest after authorities locked him out of his lab. Zhang wrote in an online post on Monday, April 29, 2024, that he and his team were suddenly notified they were being evicted from their lab, the latest in a series of setbacks, demotions and ousters since he first published the sequence in early January 2020.(AP Photo/Dake Kang)

Virologist Zhang Yongzhen, the first scientist to publish a sequence of the COVID-19 virus, walks down a street in Shanghai, China on Dec. 13, 2020. Zhang was staging a sit-in protest after authorities locked him out of his lab. Zhang wrote in an online post on Monday, April 29, 2024, that he and his team were suddenly notified they were being evicted from their lab, the latest in a series of setbacks, demotions and ousters since he first published the sequence in early January 2020.(AP Photo/Dake Kang)