NEW YORK (AP) — Nearly two years after the knife attack that nearly killed him, Salman Rushdie appears both changed and very much the same.

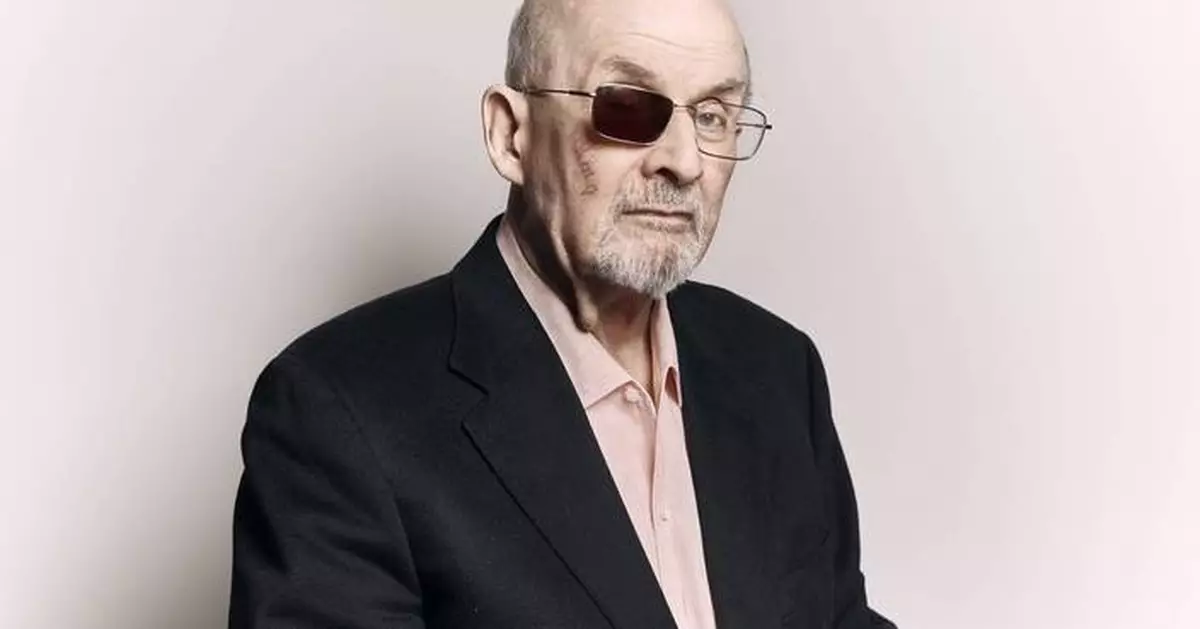

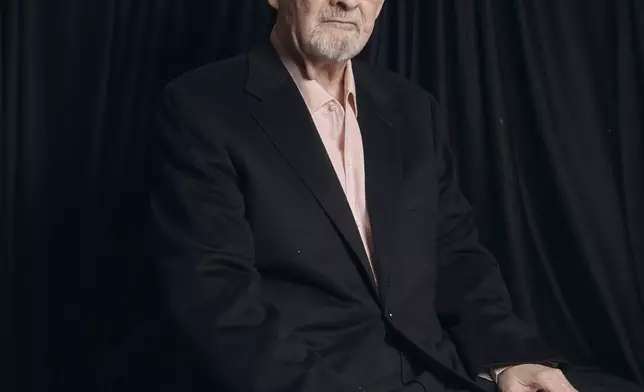

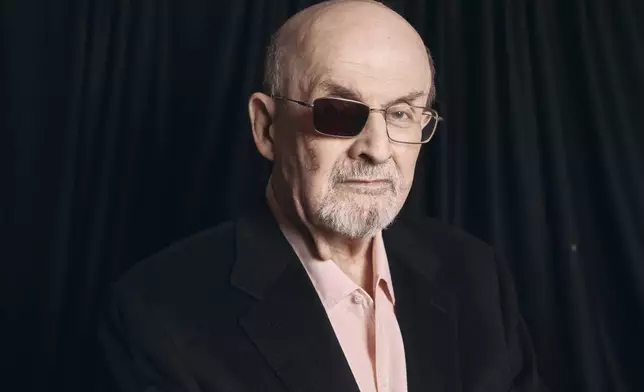

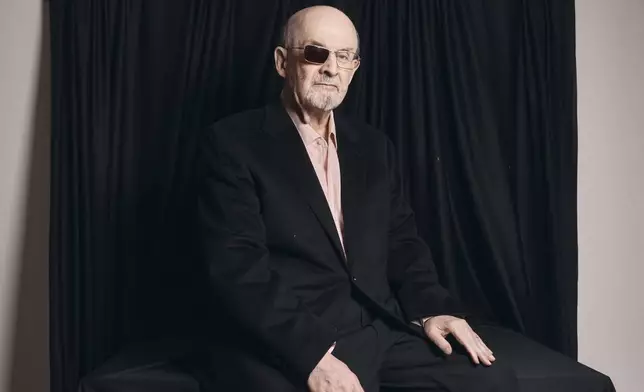

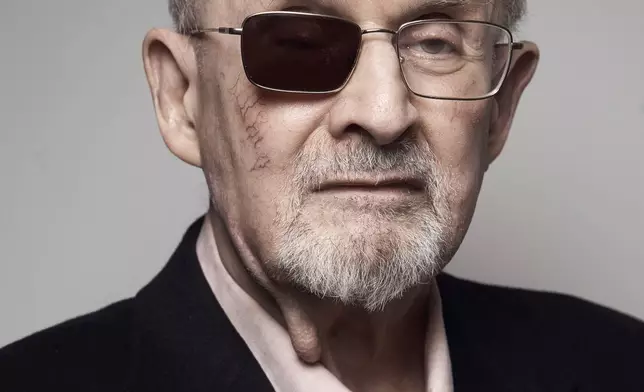

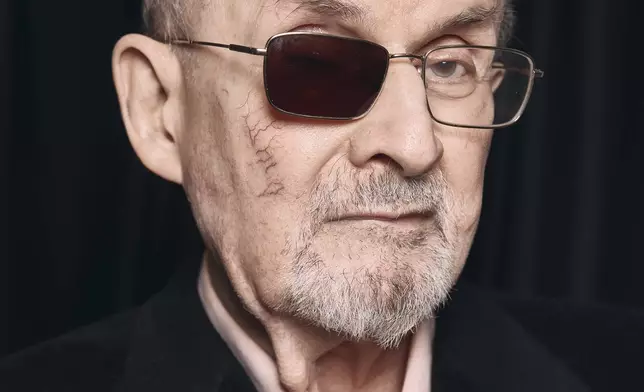

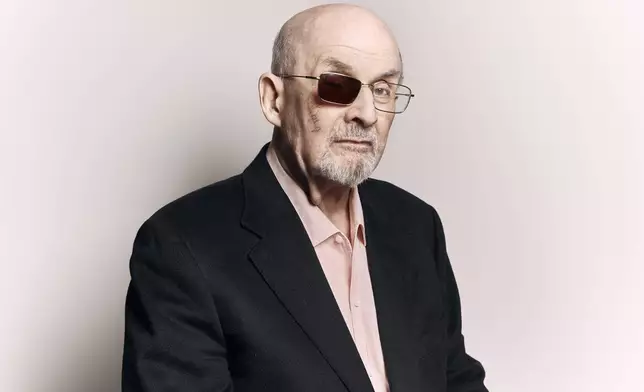

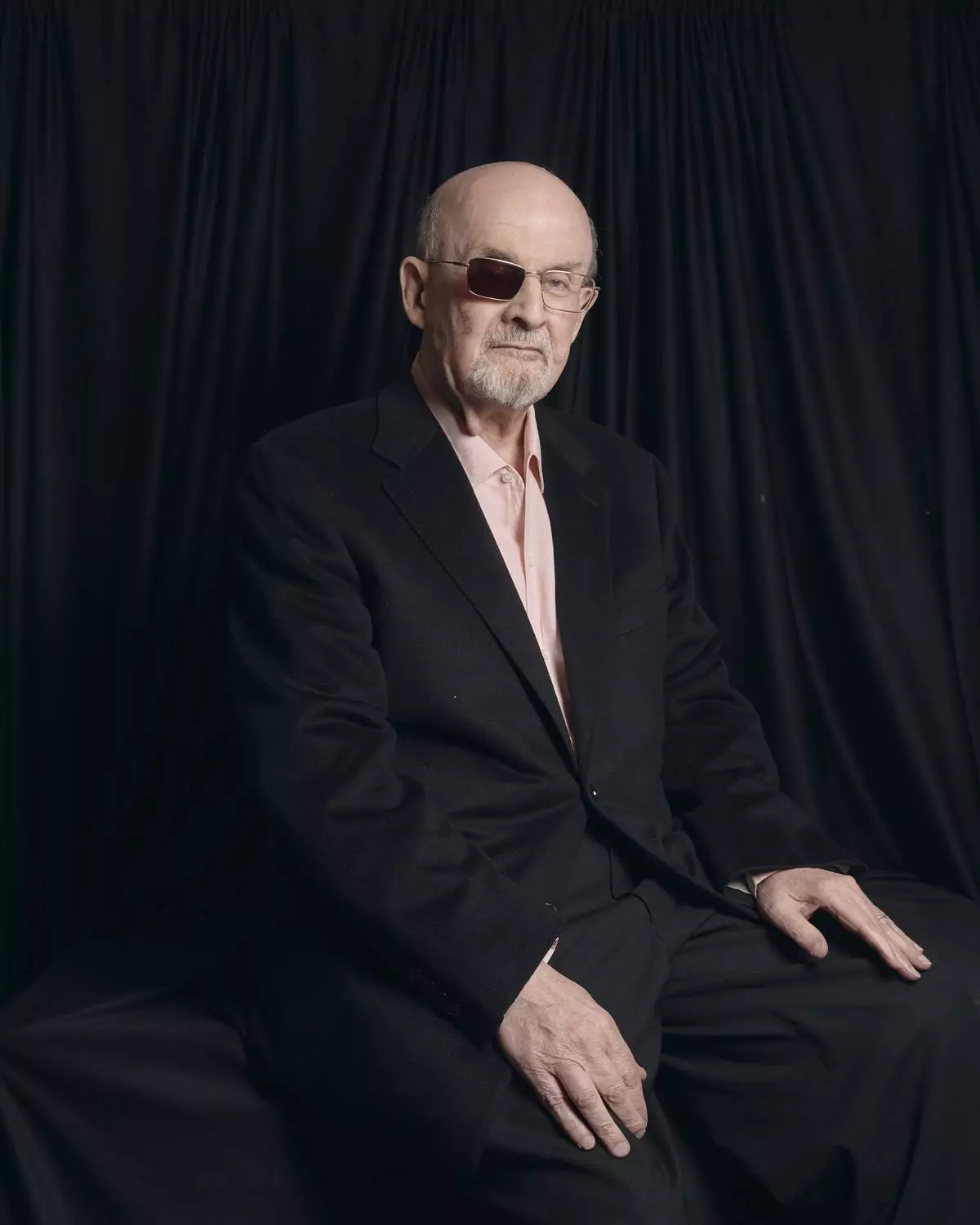

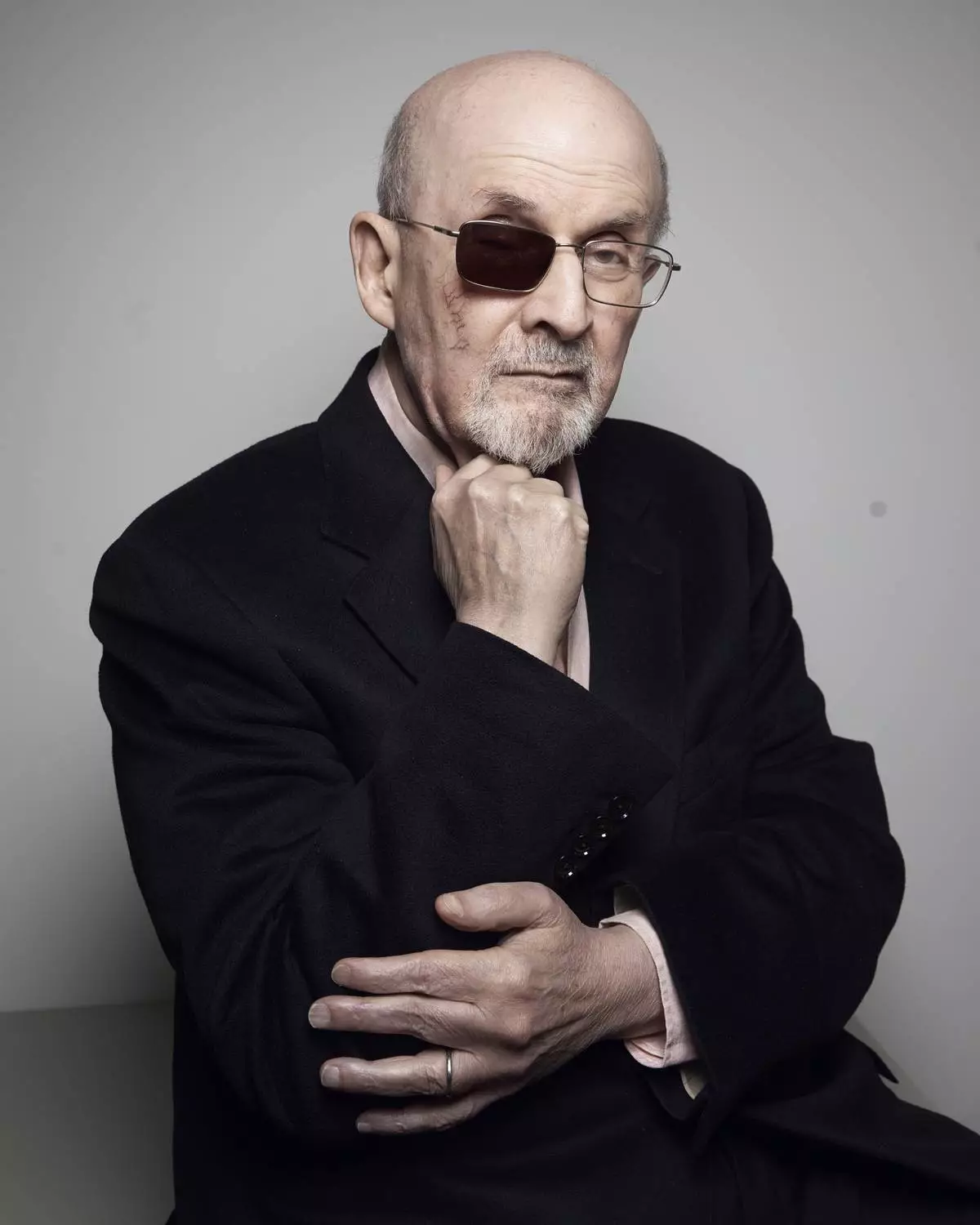

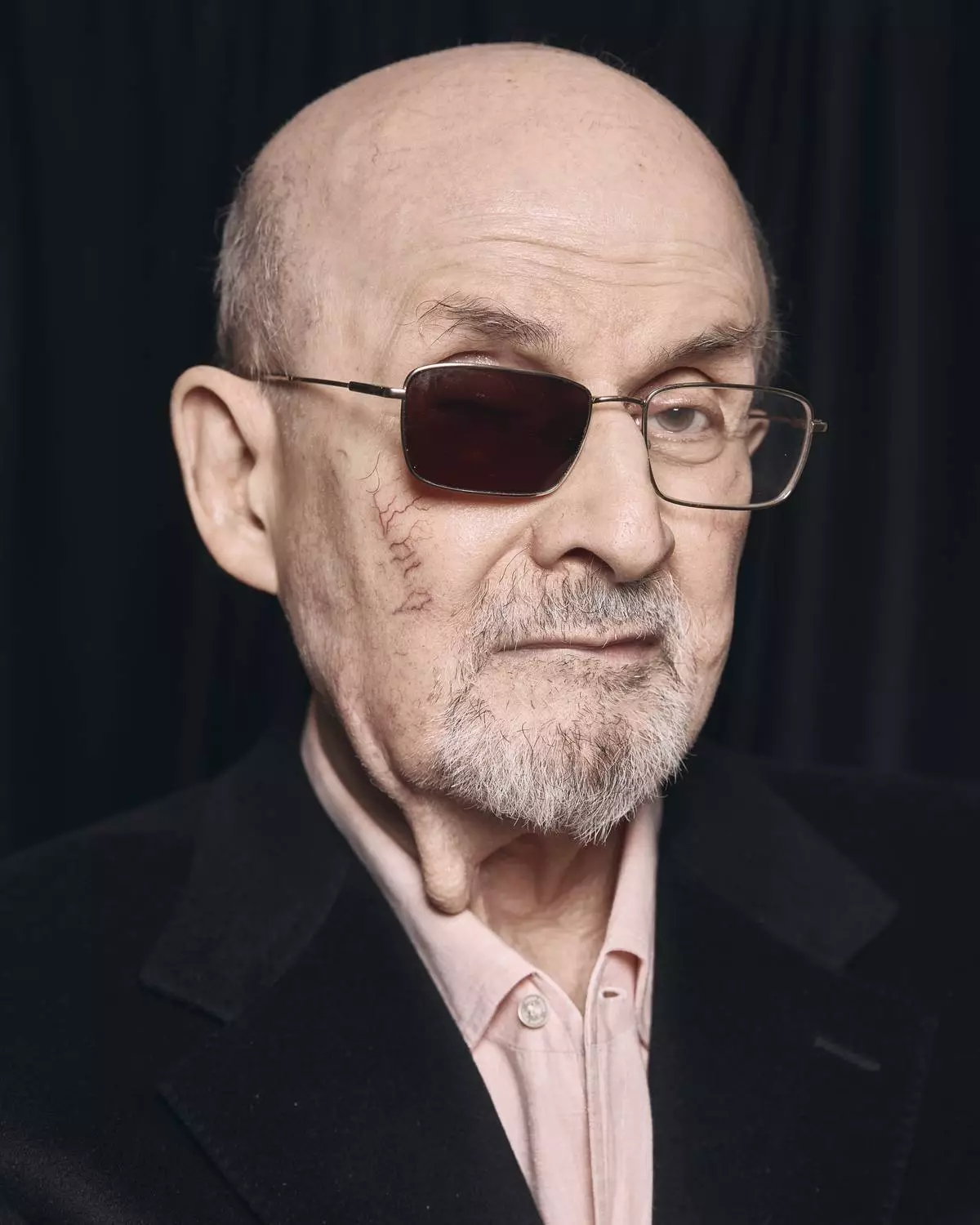

Interviewed this week at the Manhattan offices of his longtime publisher, Random House, he is thinner, paler, scarred and blind in his right eye. He speaks of “iron” in his soul and the struggle to write his next full-length work of fiction as he concentrates on promoting “Knife,” a memoir about his stabbing that he took on if only because he had no choice.

But he remains the engaging, articulate and uncensored champion of artistic freedom and the ingenious deviser of “Midnight’s Children” and other lauded works of fiction. He has been, and still is an optimist, helplessly so, he acknowledges. He also has the rare sense of confidence one can only attain through surviving one’s worst nightmare.

“In ‘Midnight’s Children’ I wrote about optimism as a disease. People get infected by it and I think I got a lifetime infection,” he says.

Chronologically, he is nearly 77, the age his father was when he died, an age he sees a kind of milestone in his own quest to beat expectations.

Internally, he feels about 25.

A self-described nice child, one who did not see himself as destined to get in trouble, Rushdie has had a life well beyond even his own boundless dreams. The 1981 Booker Prize win for “Midnight’s Children” established him as a dynamic voice of post-colonial literature. Nearly a decade later, he would reach a terrifying level of fame with “The Satanic Verses,” and the call for his death issued by Iran’s Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

Rushdie was driven into hiding. But by August 2022, he had thought himself safe enough to address a conference in western New York with minimal security: No one was on hand to stop a young assailant, Hadi Matar, from rushing the stage and stabbing him repeatedly. Matar, then 24, has been charged with attempted murder and assault.

Rushdie spoke to The Associated Press about why he wrote the explicit account of his attack, what he has learned about himself and what he might do next. This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

AP: When you started working on “Knife,” were you frightened at all?

RUSHDIE: I was worried about retraumatization, that was the worry. And the first chapter, in which the actual attack is described in great detail — that was very goddamn hard to write.

AP: You just got right to the point.

RUSHDIE: Yeah. You know, don’t beat about the bush. Because the reason this book exists is because that happened.

AP: Writers talk a lot about they don’t know how they really felt about something ...

RUSHDIE: ... Until you write it down.

AP: And is that how it was for you?

RUSHDIE: Yeah. Also, I have a very good therapist and actually this is a book written also with the help of a therapist. I was talking to him every week, and discussing what I was doing. And he was helpful, actually. Very clear thinking and helped me clear my thinking. So that was something I had not done before.

AP: You’ve discovered that you’re tougher than you thought you were.

RUSHDIE: If you had told me that this was going to happen and how would I deal with it, I would not have been very optimistic about my chances.

AP: Was there that fear in the back of your mind? You might not be able to handle this?

RUSHDIE: I’m not good with fear. I’m not good with pain. You know, I’m just an ordinary guy hoping those things don’t happen, that you don’t have to deal with fear and pain.

AP: I remember you writing about how, after the fatwa, there was a period where fiction was a struggle. Where are you in that place now?

RUSHDIE: I don’t have the next novel. I hope I will, but the only fiction I’ve written since finishing this book is a kind of story. It’s a thing I don’t know quite what to do with. It’s a story that’s about 60 pages, 65 pages long. And I’m not sure whether to think it’s like a novella or whether I want to add to it and make it more, or that I want to cut it in half and make it a story.

AP: So much of “Knife” is about reclaiming your life. Is one measure of being all the way back “I’ve got the next novel”?

RUSHDIE: That will feel good. I’m always happiest when I have a book to write.

AP: I would imagine there are a hundred different ways to look at the attack and the damage. But one way is, has it intruded upon your imagination?

RUSHDIE: Well, it did. For six months after the attack, I couldn’t even think about writing. I wasn’t physically strong enough. And when I did sit down to write, initially, I didn’t want to write this book. I actually wanted to get back to fiction, and I tried and it just seemed stupid. I just thought, “Look, something very big happened to you.” And to pretend that it didn’t and just go on telling fairy tales would seem like — I would have felt like I was avoiding the subject.

AP: Something that strikes me in this book is when the moment comes, there’s a voice inside you saying, “Well, here it is.” Even as you had gotten back to pretty much a normal life.

RUSHDIE: I did think about it in the early years, obviously, when the danger level was very high. I did think about how somebody could come out of a crowd, and, I had had dreams about it before.

AP: Was there ever that fear that maybe this was just your fate?

RUSHDIE: No, I don’t believe in fate.

AP: What do you believe in?

RUSHDIE: Well, anti-fate.

AP: Coincidence?

RUSHDIE: Taking charge of your life is what I believe in.

AP: One of the things I remember thinking when I first heard the news of the attacker was how young the attacker was. He wasn’t born when you wrote “Satanic Verses.”

RUSHDIE: No, not for 10 years or something.

AP: It’s as if you and that book are somehow fixed in the subconscious.

RUSHDIE: And it’s not even the book because nobody takes the trouble to read it. It’s just the name of that book associated with me, me demonized as a bad guy. But I don’t know this man, you know? I mean, I know the little bits that we have been told — that his mother said after he came back from visiting his father in Lebanon that he was very different, much more religion oriented, critical of her for not having taught him properly about religion. And then for four years, in a basement.

AP: It’s like you’re some kind of abstraction out there.

RUSHDIE: I don’t know why it became me that after all this very long time in the basement, playing computer games and watching videos. Why it became me that he fixated on.

AP: When you were growing up, did you imagine yourself as the type of person who would get in trouble?

RUSHDIE: Not at all. I was a very quiet kid. I was really well behaved. My sister, who’s one year younger than me, she was the naughty one. She would beat people up for me and I would get her out of trouble.

AP: You talk about you happy childhood, you’re a nice boy. But “Midnight’s Children,” so much of your work, you’re trying to get some kind of reaction.

RUSHDIE: You’re trying to write a big book, you know?

AP: And a book you probably knew might make somebody unhappy.

RUSHDIE: Oh, yeah, but who cares, you know?

AP: Where does that comes from?

RUSHDIE: I had it as a child. I had the confidence of being loved and supported by my parents. And I’ve always been kind of academically excellent. So you grow up in that way. You give yourself permission to do things. Because you’ve been treated in that way. And also, of course, remember, I was 21 in 1968. I’m a child of the '60s.

AP: How changed, if at all, do you think you are compared to two years ago?

RUSHDIE: I’m still myself, you know, and I don’t feel other than myself. But there’s a little iron in the soul, I think. And I also think the thing that happens when you get really a close up look at death — that’s as close as you can get without actually doing the dance of death and heading off to nowhere — it stays with you.

AP: What does that mean?

RUSHDIE: It means there’s a shadow. It means the presence of the ending.

AP: How old do you feel? Internally.

RUSHDIE: (laughing) About 25.

AP: You do?

RUSHDIE: I think one of the great things about writing — you need a kind of youthfulness to do it, because it requires energy, imagination, dreaming. It’s a young man’s game. I’ve said somewhere that when you’re young and you’re writing, you have to fake wisdom. When you’re older and you’re writing, you have to fake energy.

AP: Can you fake energy?

RUSHDIE: Well, I’ve tried.

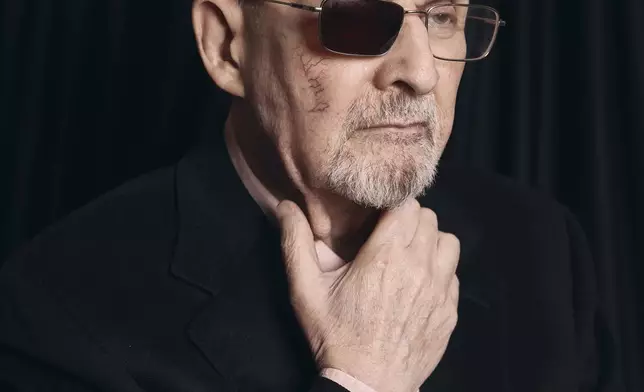

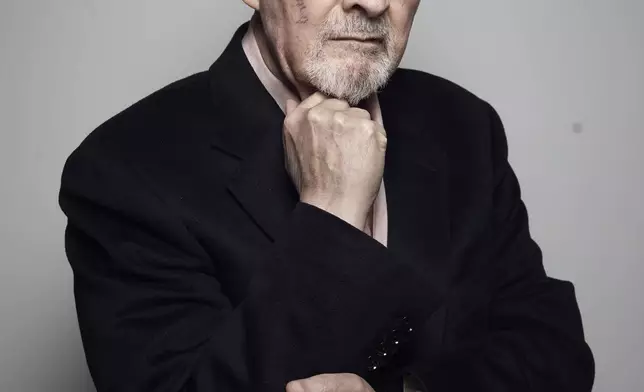

Salman Rushdie poses for a portrait to promote his book "Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder" on Thursday, April 18, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Andres Kudacki)

Salman Rushdie poses for a portrait to promote his book "Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder" on Thursday, April 18, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Andres Kudacki)

Salman Rushdie poses for a portrait to promote his book "Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder" on Thursday, April 18, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Andres Kudacki)

Salman Rushdie poses for a portrait to promote his book "Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder" on Thursday, April 18, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Andres Kudacki)

Salman Rushdie poses for a portrait to promote his book "Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder" on Thursday, April 18, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Andres Kudacki)

Salman Rushdie poses for a portrait to promote his book "Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder" on Thursday, April 18, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Andres Kudacki)

Salman Rushdie poses for a portrait to promote his book "Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder" on Thursday, April 18, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Andres Kudacki)

Salman Rushdie poses for a portrait to promote his book "Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder" on Thursday, April 18, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Andres Kudacki)