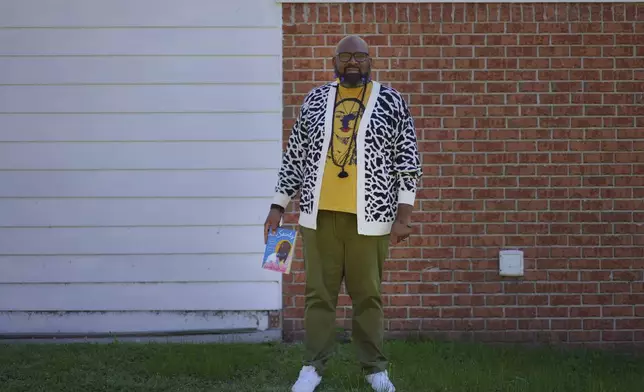

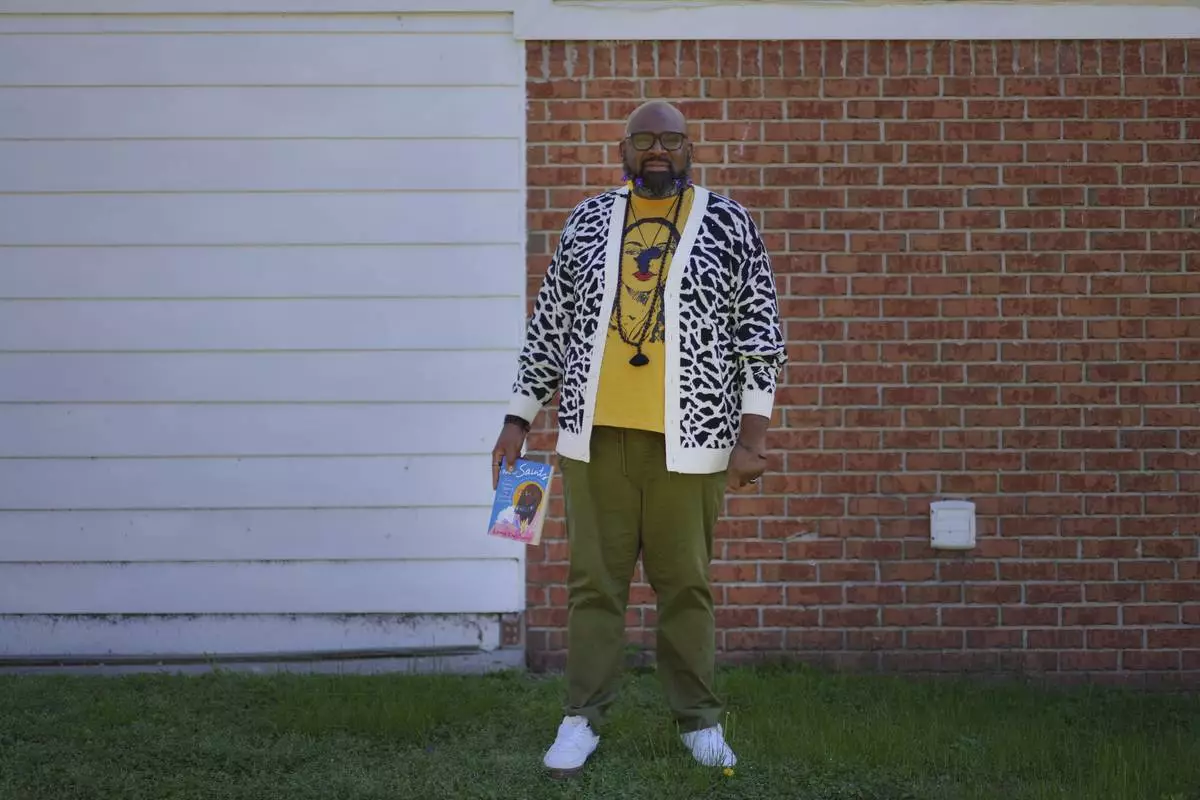

ROME, Ga (AP) — Instead of traditional maroon and gold Tibetan Buddhist robes, Lama Rod Owens wore a white animal print cardigan over a bright yellow T-shirt with an image of singer Sade, an Africa-shaped medallion and mala beads — the most recognizable sign of his Buddhism.

"Being a Buddhist or a spiritual leader, I got rid of trying to wear the part because it just wasn’t authentic to me,” said Owens, 44, who describes himself as a Black Buddhist Southern Queen.

“For me, it’s not about looking like a Buddhist. It’s about being myself,” he said at his mother’s home in Rome, Georgia. "And I like color.”

The Harvard Divinity School -educated lama and yoga teacher blends his training in the Kagyu School of Tibetan Buddhism with pop culture references and experiences from his life as a Black, queer man, raised in the South by his mother, a pastor at a Christian church.

Today, he is an influential voice in a new generation of Buddhist teachers, respected for his work focused on social change, identity and spiritual wellness.

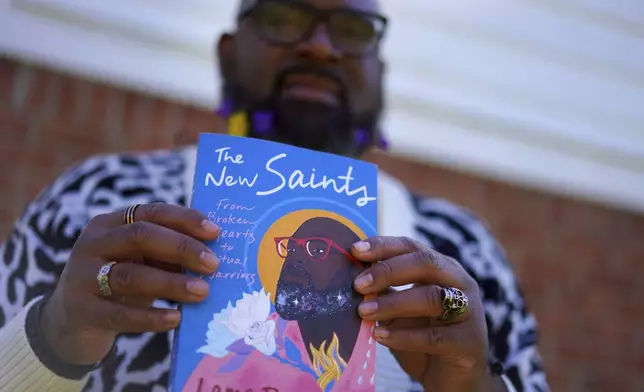

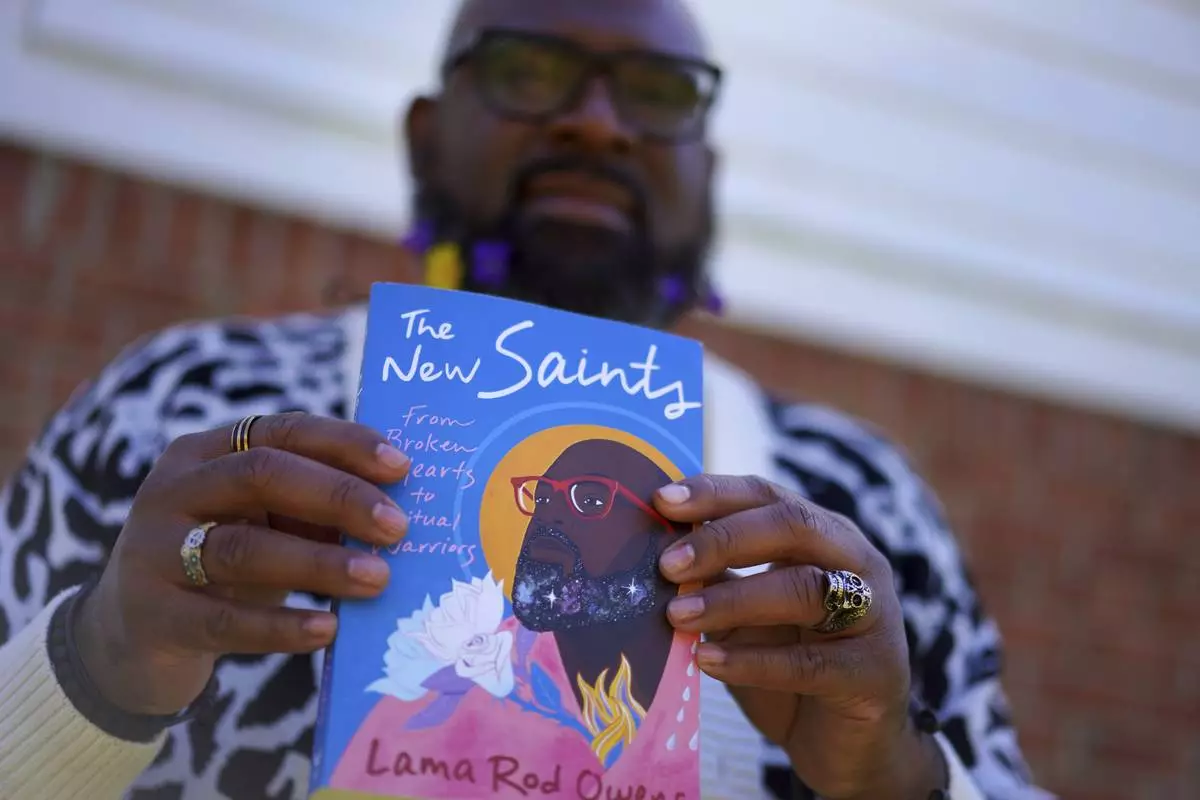

On the popular mindfulness app Calm, his wide-ranging courses include “Coming Out,” “Caring for your Grief,” and “ Radical Self-Care ” (sometimes telling listeners to “shake it off” like Mariah Carey). In his latest book, “ The New Saints,” he highlights Christian saints and spiritual warriors, Buddhist bodhisattvas and Jewish tzaddikim among those who have sought to free people from suffering.

“Saints are ordinary and human, doing things any person can learn to do,” Owen writes in his book, where he combines personal stories, traditional teachings and instructions for meditations.

“Our era calls for saints who are from this time and place, speak the language of this moment, and integrate both social and spiritual liberation,” he writes.“ I believe we all can and must become New Saints.”

But how? “It’s not about becoming a superhero,” he said, stressing the need to care for others.

And it’s not reserved for the canonized. “Harriet Tubman is a saint for me,” he said about the 19th century Black abolitionist known for helping enslaved people escape to freedom on the Underground Railroad. “She came to this world and said, ‘I want people to be free.’”

Owens grew up in a devout Baptist and Methodist family. His life revolved around his local church.

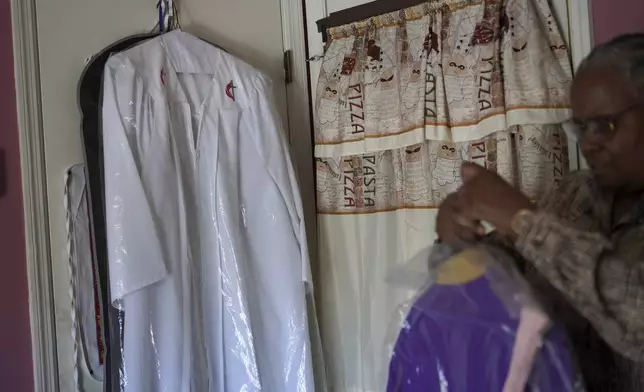

When he was 13, his mother, who owns a baseball cap that reads: “God’s Girl,” became a United Methodist minister. He calls her the single greatest impact in his life.

“Like a lot of Black women, she embodied wisdom and resiliency and vision. She taught me how to work. And she taught me how to change because I saw her changing.”

He was inspired by her commitment to a spiritual path, especially when she went against the wishes of some in her family, who — like in many patriarchal religions — believed a woman should not lead a congregation.

“I’m very proud of him,” said the Rev. Wendy Owens, who sat near her son in her living room, decorated with their photographs and painted portraits.

“He made his path. He walked his path, or he might have even ran his path,” she said. “Don’t know how he got there, but he got there.”

A life devoted to spirituality seemed unlikely for her son after he entered Berry College, a nondenominational Christian school. It didn’t deepen his relationship with Christianity. Instead, he stopped attending church. He wanted to “develop a healthy sense of self-worth” about his queerness, and was dismayed by conservative religious views on gender and sexuality. He felt the way that God had been presented to him was too rigid, even vengeful. So, in his words, he “broke up with God.”

His new religion, he said, became service. He trained as an advocate for sexual assault survivors, and volunteered for projects on HIV/AIDS education, homelessness, teen pregnancy and substance abuse.

“Even though I wasn’t doing this theology anymore, what I was definitely doing was following the path of Jesus: feeding people, sheltering people.”

After college, he moved to Boston and joined Haley House, a nonprofit partly inspired by the Catholic Worker Movement that runs a soup kitchen and affordable housing programs.

There, he said, he met people across a range of religious traditions — “from Hinduism to Christian Science to all the denominations of Christianity, Buddhists, Wiccans, Muslims. Monastics from different traditions, everyone.”

A Buddhist friend gave him a book that helped him find his spiritual path: “Cave in the Snow,” by Tibetan Buddhist nun Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo.

The British-born nun spent years isolated in a cave in the Himalayas to follow the rigorous path of the most devoted yogis. She later founded a nunnery in India focused on giving women in Tibetan Buddhism some of the opportunities reserved for monks.

“When I started exploring Buddhism, I never thought, ’Oh, Black people don’t do this, or maybe this is in conflict with my Christian upbringing,’” Owens said.“ What I thought was: ’Here’s something that can help me to suffer less. ... I was only interested in how to reduce harm against myself and others.”

At Harvard Divinity School, he was again immersed in religious diversity — even a Satanist was there.

“What I love about Rod is that he’s deeply himself no matter who he’s with,” said Cheryl Giles, a Harvard Divinity professor who mentored him and who now considers him one of her own teachers.

“When I think of him, I think of this concept of Boddhisatva in Buddhism, the deeply compassionate being who is on the path to awakening and sees the suffering of the world and makes a commitment to help liberate others,” said Giles.

“And I love,” she said, "that he’s Black and Buddhist.”

Through Buddhism, mindfulness and long periods of silent retreats, Owens eventually reconciled with God.

“God isn’t some old man sitting on a throne in the clouds, who’s, like, very temperamental,” he said. “God is space and emptiness and energy. God is always this experience, inviting us back through our most divine, sacred souls. God is love.”

His schedule keeps him busy these days — appearing in podcasts and social media, speaking to college students and leading meditations, yoga and spiritual retreats across the world.

So much inspires him. He wrote his latest book listening to Beyonce and thinking about the work of choreographer Alvin Ailey. There’s Toni Morrison and James Baldwin. He loves Tony Kushner’s “Angels in America.” And pioneering fashion journalist Andre Leon Talley of Vogue magazine, who he says taught him to appreciate beauty.

“I want people to feel the same way when they experience something that I talk about or write about,” Owens said. “That’s part of the work of the artist — to help us to feel and to not be afraid to feel. To help us dream differently, inspire us and shake us out of our rigidity to get more fluid.”

__

Associated Press journalist Jessie Wardarski contributed to this report.

__

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

Lama Rod Owens holds his Buddhist mala beads made of lava rock used for prayer and meditation while at his childhood home in Rome, Georgia on Saturday, March 30, 2024. Owens, a self-proclaimed Black Buddhist Southern Queen, grew up Christian and was raised by his Methodist minister mother. Today, he is an influential voice in a new generation of Buddhist teachers, respected for his work focused on social change, identity and spiritual wellness. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Lama Rod Owens stands for a portrait outside of his childhood church, The Metropolitan United Methodist Church in Rome, Georgia, on Saturday, March 30, 2024. Today Owens is an influential voice in a new generation of Buddhist teachers. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

The sun sits behind the Metropolitan United Methodist Church in Rome, Georgia on Sunday, March 31, 2024. This was the local parish Lama Rod Owens attended as a child. Today, he is an influential voice in a new generation of Buddhist teachers. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Lama Rod Owens sits in the yard of his childhood home in Rome, Georgia, on Saturday, March 30, 2024. Owens is an influential voice in a new generation of Buddhist teachers, respected for his work focused on social change, identity and spiritual wellness. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Lama Rod Owens holds his latest book, "The New Saints," which highlights Christian saints and spiritual warriors, Buddhist bodhisattvas and Jewish tzaddikim among those who have sought to free people from suffering on Saturday, March 30, 2024, in Rome, Georgia. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Lama Rod Owens poses for a portrait with his beard covered in flowers in the yard of his childhood home in Rome, Georgia on Saturday, March 30, 2024. Owens is an influential voice in a new generation of Buddhist teachers, respected for his work focused on social change, identity and spiritual wellness. His latest book is entitled "The New Saints," which highlights Christian saints and spiritual warriors, Buddhist bodhisattvas and Jewish tzaddikim among those who have sought to free people from suffering. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Wendy Owens, a United Methodist Minister and mother of Lama Rod Owens, shows her robes hanging in her home on Saturday, March 30, 2024, in Rome Georgia. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Wendy Owens, a United Methodist Minister, listens to her son, Lama Rod Owens, at her home in Rome, Georgia on Saturday, March 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Lama Rod Owens holds his latest book, "The New Saints," which highlights Christian saints and spiritual warriors, Buddhist bodhisattvas and Jewish tzaddikim among those who have sought to free people from suffering on Saturday, March 30, 2024, in Rome, Georgia. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Lama Rod Owens lies in the yard of his childhood home while he poses for a portrait in Rome, Georgia,on Saturday, March 30, 2024. Owens, a self-proclaimed Black Buddhist Southern Queen, grew up Christian and was raised by his Methodist minister mother. Today, he is an influential voice in a new generation of Buddhist teachers, respected for his work focused on social change, identity and spiritual wellness. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)