PANAMA CITY (AP) — President Donald Trump’s insistence Monday that he wants the Panama Canal back under U.S. control fed nationalist sentiment and worry in Panama, home to the critical trade route and a country familiar with U.S. military intervention.

“American ships are being severely overcharged and not treated fairly in any way, shape or form, and that includes the United States Navy. And above all, China is operating the Panama Canal,” Trump said Monday.

Click to Gallery

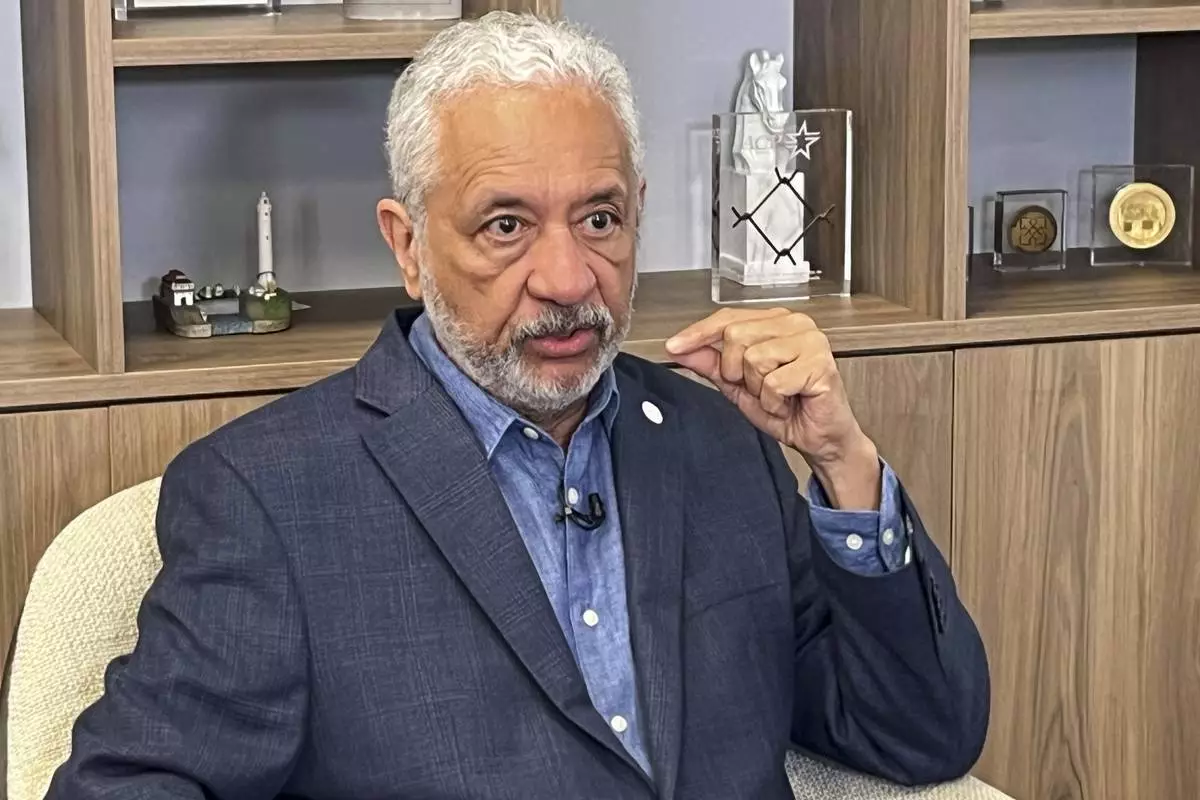

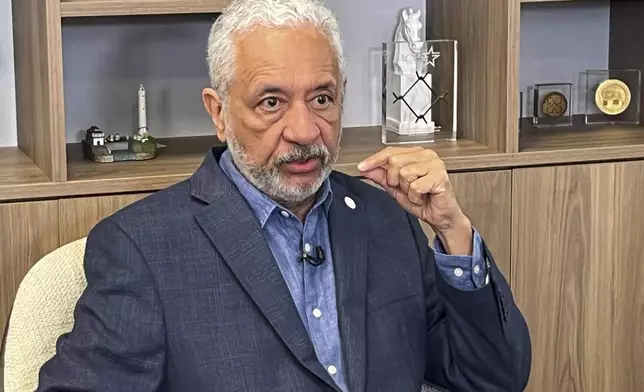

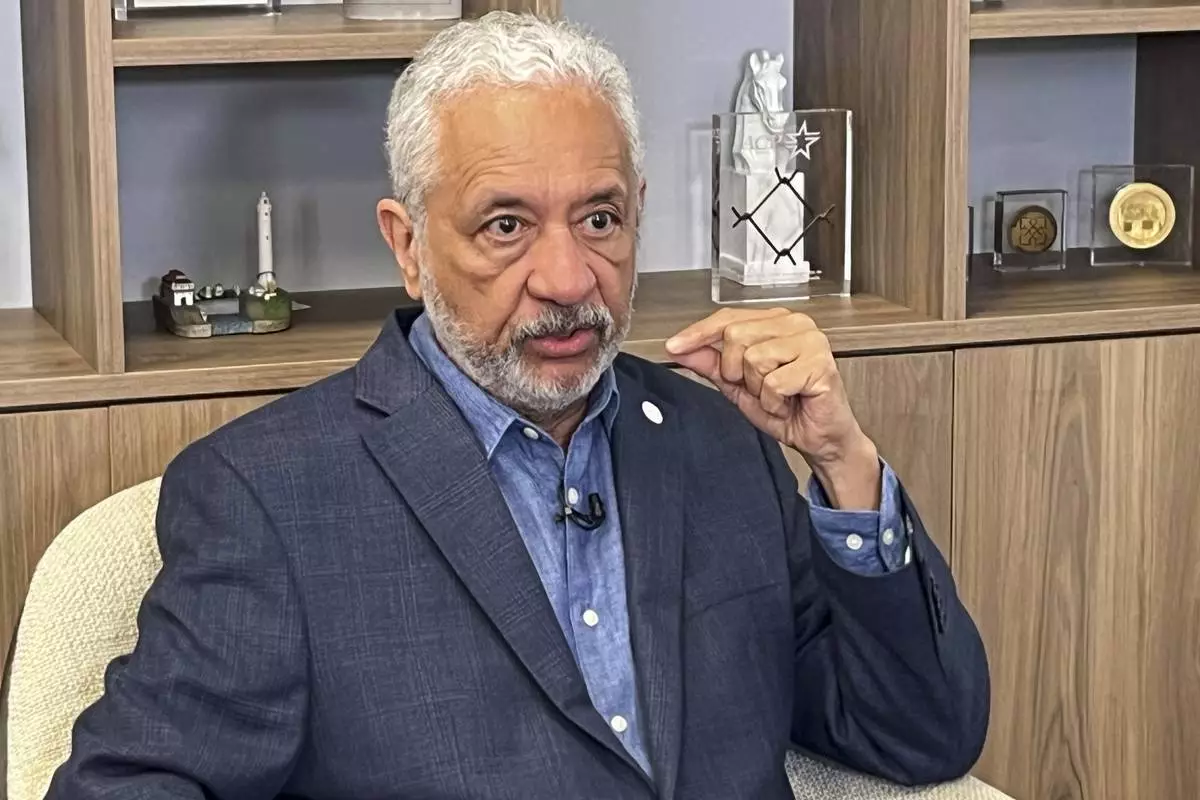

Panama Canal Administrator Ricaurte Vásquez addresses President-elect Donald Trump's suggestion that the U.S. should retake control of the Panama Canal during an interview with Associated Press in his office Friday, Jan. 10, 2025, in Panama City, Panama. (AP Photo/Abraham Terán)

President Donald Trump signs an executive order on TikTok in the Oval Office of the White House, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

FILE - Looking north from the lighthouse on the west wall is the Gatun middle locks of the Panama Canal in the final stages of construction on June 25, 1913. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - A cargo ship sails through the Miraflores locks of the Panama Canal, in Panama City, on Sept. 9, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix, File)

FILE - President Jimmy Carter applauds and General Omar Torrijos waves after the signing and exchange of treaties in Panama City on June 16, 1978, giving control of the Panama Canal to Panama in 2000. At far right is Zbigniew Brzezinski, Carterís National Security Advisor. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - A cargo ship traverses the Agua Clara Locks of the Panama Canal in Colon, Panama, Sept. 2, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix, File)

In the capital, some Panamanians saw Trump’s remarks as a way of applying pressure on Panama for something else he wants: better control of migration through the Darien Gap. Others recalled the 1989 U.S. invasion of Panama with concern.

Panama President José Raúl Mulino responded forcefully, as he did after Trump’s initial statement last month that the U.S. should consider repossessing the canal, saying the canal belongs to his country of 4 million and will remain Panama’s territory.

Panama's U.N. Mission sent Mulino's statement to the U.N. Security Council. The statement rejected “in its entirety" Trump's comments on the canal and said: “There is no presence of any nation in the world that interferes with our administration.”

Luis Barrera, a 52-year-old cab driver, said Panama had fought hard to get the canal back and has expanded it since taking control.

“I really feel uncomfortable because it’s like when you’re big and you take a candy from a little kid,” Barrera said.

At a rally in Phoenix in December, Trump said he might try to get the canal back after it was “foolishly” ceded to Panama. He complained that shippers were overcharged and that China had taken control of the key shortcut between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.

Earlier this month, Trump wouldn’t rule out using military force to take it back.

The United States built the canal in the early 1900s as it looked for ways to facilitate the transit of commercial and military vessels between its coasts. Washington relinquished control of the waterway to Panama on Dec. 31, 1999, under a treaty signed in 1977 by President Jimmy Carter.

The canal is a point of pride for Panamanians. On Dec. 31, they celebrated the 25th anniversary of the handover, and days later they commemorated the deaths of 21 Panamanians who died at the hands of the U.S. military decades earlier.

On Jan. 9, 1964, students protested in the then-U.S. controlled canal zone over not being allowed to fly Panama’s flag at a secondary school there. The protests expanded to general opposition to the U.S. presence in Panama and U.S. troops got involved. A group of protesters this year burned an effigy of Trump.

The canal’s administrator, Ricaurte Vásquez, said this month that China is not in control of the canal and that all nations are treated equally under a neutrality treaty.

He said Chinese companies operating in the ports on either end of the canal were part of a Hong Kong consortium that won a bidding process in 1997. He added that U.S. and Taiwanese companies operate other ports along the canal as well.

Omayra Avendaño, who works in real estate, said Trump’s threat should be taken seriously.

“We should be worried,” she said. “We don’t have an army and he’s said he would use force.”

On Dec. 20, 1989, the U.S. military invaded Panama to remove dictator Manuel Noriega. Some 27,000 troops were tasked by then-President George H.W. Bush with capturing Noriega, protecting the lives of Americans living in Panama and restoring democracy to the country that a decade later would take over control of the Panama Canal.

Avendaño said she was 11 years old the last time the U.S. invaded her country and hoped Panama’s current government would seek international support to head off Trump’s designs on the canal.

“I remember the disaster that it was,” she said.

Panama Canal Administrator Ricaurte Vásquez addresses President-elect Donald Trump's suggestion that the U.S. should retake control of the Panama Canal during an interview with Associated Press in his office Friday, Jan. 10, 2025, in Panama City, Panama. (AP Photo/Abraham Terán)

President Donald Trump signs an executive order on TikTok in the Oval Office of the White House, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

FILE - Looking north from the lighthouse on the west wall is the Gatun middle locks of the Panama Canal in the final stages of construction on June 25, 1913. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - A cargo ship sails through the Miraflores locks of the Panama Canal, in Panama City, on Sept. 9, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix, File)

FILE - President Jimmy Carter applauds and General Omar Torrijos waves after the signing and exchange of treaties in Panama City on June 16, 1978, giving control of the Panama Canal to Panama in 2000. At far right is Zbigniew Brzezinski, Carterís National Security Advisor. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - A cargo ship traverses the Agua Clara Locks of the Panama Canal in Colon, Panama, Sept. 2, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix, File)

NEW YORK (AP) — Less than 24 hours after throngs of ecstatic supporters poured into Manhattan for his history-making inauguration, Zohran Mamdani began his first full day of work with a routine familiar to many New Yorkers: trudging to the subway from a cramped apartment.

Bundled against the frigid temperature and seemingly fighting off a cold, he set out Friday morning from the one-bedroom apartment in Queens that he shares with his wife. But unlike most commuters, Mamdani's trip was documented by a photo and video crew, and periodically interrupted by neighbors wishing him luck.

The 34-year-old democratic socialist, whose victory was hailed as a watershed moment for the progressive movement, has now begun the task of running the nation’s largest city: signing orders, announcing appointments, facing questions from the press — and answering for some of the actions he took in his first hours.

But first, the symbolism-laden day one commute.

Flanked by security guards and a small clutch of aides on a Manhattan-bound train, he agreed to several selfies with wide-eyed riders, then moved to a corner seat of the train to review his briefing materials.

When a pair of French tourists, confused by the hubbub, approached Mamdani, he introduced himself as “the new mayor of New York.” They seemed doubtful. He held up the morning’s copy of the New York Daily News, featuring his smiling face, as proof.

Mamdani, a Democrat, is hardly alone among city mayors in using the transit system to communicate relatability. His predecessor, Eric Adams, also rode the subway on his first day, and both Bill de Blasio and Michael Bloomberg made a habit out of it, particularly when seeking to make a political point.

Within minutes of Mamdani entering City Hall, the images of him riding public transit had lit up social media.

If the ride served as a well-timed photo-op, it also seemed to reflect Mamdani's pledge, made in his inaugural speech, to ensure his “government looks and lives like the people it represents.”

His other early actions have also seemed to underscore that priority.

After centering much of his campaign on making rent cheaper for New Yorkers, Mamdani raced from his inauguration ceremony Thursday to a Brooklyn apartment building lobby, drawing boisterous cheers from the tenants union as he pledged that the city would ramp up an ongoing legal fight against the allegedly negligent landlord.

Mamdani’s next action, meanwhile, showed the unusual scrutiny faced by his nascent administration, particularly around his criticism of Israel and outspoken support for the Palestinian cause.

In an effort to give his government a “clean slate,” he revoked a slate of executive orders issued by Adams late in his term, including two related to Israel: one that officially adopted a contentious definition of antisemitism that includes certain criticism of Israel, and another barring city agencies and employees from boycotting or divesting from the country.

The move drew swift backlash from some Jewish groups, including allegations from the Israeli government posted to social media that Mamdani had poured “antisemitic gasoline on an open fire.”

When a journalist on Friday asked about the revoked orders, Mamdani read from prepared remarks, promising his administration would be “relentless in its effort to combat hate and division.” He noted that he had left in place the Mayor’s Office to Combat Antisemitism.

Mamdani also announced the creation of a “mass engagement” office, which he said would continue the work his campaign’s field operation did to bring more New Yorkers into the political fold.

Ringed by supporters and passersby who stood several rows deep, phones in the air, to catch a glimpse of the new mayor, Mamdani then acknowledged the weight of the current moment.

“We have an opportunity where New Yorkers are allowing themselves to believe in the possibility of city government once again,” he said. “That is not a belief that will sustain itself in the absence of action.”

Also on Mamdani’s to-do list: Moving to the mayor’s official residence, a stately mansion in the Upper East Side neighborhood of Manhattan, before the lease on his Queens apartment ends later this month.

Associated Press writer Jennifer Peltz contributed to this report.

New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani attends a press conference in the Brooklyn borough of New York, Friday, Jan. 2, 2026. (AP Photo/Eduardo Munoz Alvarez)

New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani reads a newspaper on the subway on his way to City Hall in New York, Friday, Jan. 2, 2026. (AP Photo/Eduardo Munoz Alvarez)

New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani arrives at the City Hall subway station in New York, Friday, Jan. 2, 2026. (AP Photo/Eduardo Munoz Alvarez)

New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani greets passengers on a subway to City Hall in New York, Friday, Jan. 2, 2026. (AP Photo/Eduardo Munoz Alvarez)

New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani checks his agenda on the subway on his way to City Hall in New York, Friday, Jan. 2, 2026. (AP Photo/Eduardo Munoz Alvarez)