CAPE TOWN, South Africa (AP) — The names are carved on poles of African hardwood that are set upright as if reaching for the sun. No one knows where the men they represent were buried.

But their names, forgotten for more than a century, have been revived and are now written in the records of history.

Click to Gallery

Britain's Princess Anne, the President of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, centre, in conversation with official during the opening of a memorial dedicated to more than 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

A Royal Marine officer attends the opening of a memorial dedicated to more than 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

Egyptian geese with goslings are seen next to an African "iroko" hardwood post bearing names and the date of death of 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

Britain's Princess Anne, the President of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, walks in between an African "iroko" hardwood post bearing names and the date of death of 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

Lwanda Sindaphi, a praise poet performs a cultural tribute at the opening of a memorial dedicated to more than 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

Britain's Princess Anne, the President of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, attends the opening of a memorial dedicated to more than 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

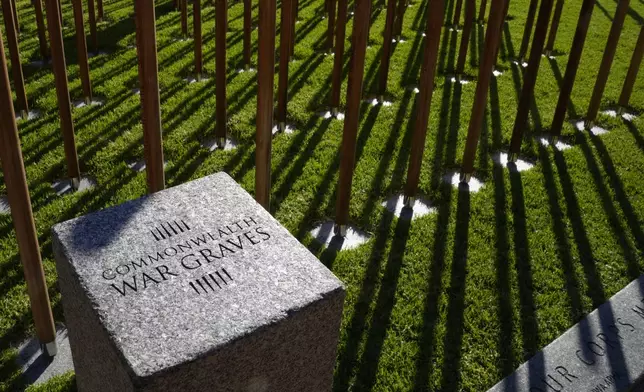

A memorials plaque dedicated to more than 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

Britain's Princess Anne, the President of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, attends the opening of a memorial dedicated to more than 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

Britain's Princess Anne, the President of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, walks in between an African "iroko" hardwood post bearing names and the date of death of 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

A memorials plaque dedicated to more than 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

A praise poet performs a cultural tribute at the opening of a memorial dedicated to more than 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

African "iroko" hardwood posts bear the names and the date of death of 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

Black South African servicemen who died in non-combat roles on the Allied side during World War I and have no known grave have been recognized with a memorial featuring 1,772 names.

An inscription on a granite block at the memorial in Cape Town says: “Your legacies are preserved here.”

Because they were Black, they were not allowed to carry arms. They were members of the Cape Town Labor Corps, transporting food, ammunition and other supplies and building roads and bridges during the Great War.

They didn't serve in Europe but in the fringe battles in Africa, where Allied forces fought in the then-German colonies of German South West Africa (now Namibia) and German East Africa (now Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi).

The men made the same ultimate sacrifice as around 10 million others who died serving in armies in the 1914-1918 war.

After the war, they were not recognized because of the racial policies of British colonialism and then South Africa's apartheid regime.

The memorial finally rights a historical wrong, said the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, the British organization that looks after war graves and built the new memorial in Cape Town's oldest public garden.

The memorial was opened Wednesday by Britain's Princess Anne, the commission's president.

“It ensures the names and stories of those who died will echo in history for future generations,” Princess Anne said. "It is important to recognize that those we have come to pay tribute to have gone unacknowledged for too long. We will remember them.”

When her speech ended, a lone soldier played “The Last Post” on his bugle to commemorate the Black servicemen as war dead, 106 years, two months and 11 days after the end of World War I.

While South Africa has several memorials dedicated to its white soldiers who died in both world wars, the Black servicemen's contribution was ignored for decades.

It was in danger of being lost forever until a researcher found evidence of their service in South African army documents around 10 years ago, said Commonwealth War Graves Commission operational manager David McDonald, who oversaw the South African project.

Researchers discovered the more than 1,700 Black servicemen and the war graves commission traced the families of six of the dead, most of them from deeply rural South African regions.

Four of those families were represented at Wednesday's ceremony. They laid wreaths at the foot of the memorial and were able to touch the individual poles dedicated to their lost relatives and where their names are inscribed.

“It made us very proud. It made us very happy,” said Elliot Malunga Delihlazo, whose great-grandfather, Bhesengile, was among those honored.

Delihlazo said his family only knew that Bhesengile went to war and never came back.

“Although it pains us ... that we can’t find the remains, at last we know that he died in 1917,” Delihlazo said. “Now the family knows. Now, at last, we know.”

AP Africa news: https://apnews.com/hub/africa

Britain's Princess Anne, the President of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, centre, in conversation with official during the opening of a memorial dedicated to more than 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

A Royal Marine officer attends the opening of a memorial dedicated to more than 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

Egyptian geese with goslings are seen next to an African "iroko" hardwood post bearing names and the date of death of 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

Britain's Princess Anne, the President of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, walks in between an African "iroko" hardwood post bearing names and the date of death of 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

Lwanda Sindaphi, a praise poet performs a cultural tribute at the opening of a memorial dedicated to more than 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

Britain's Princess Anne, the President of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, attends the opening of a memorial dedicated to more than 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

A memorials plaque dedicated to more than 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

Britain's Princess Anne, the President of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, attends the opening of a memorial dedicated to more than 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

Britain's Princess Anne, the President of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, walks in between an African "iroko" hardwood post bearing names and the date of death of 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

A memorials plaque dedicated to more than 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

A praise poet performs a cultural tribute at the opening of a memorial dedicated to more than 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

African "iroko" hardwood posts bear the names and the date of death of 1,700 Black South African servicemen who died in non-combatant roles in World War I and have no known grave, in Cape Town, South Africa, Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Nardus Engelbrecht)

DUBAI, United Arab Emirates (AP) — U.S. President Donald Trump said Iran wants to negotiate with Washington after his threat to strike the Islamic Republic over its bloody crackdown on protesters, a move coming as activists said Monday the death toll in the nationwide demonstrations rose to at least 544.

Iran had no immediate reaction to the news, which came after the foreign minister of Oman — long an interlocutor between Washington and Tehran — traveled to Iran this weekend. It also remains unclear just what Iran could promise, particularly as Trump has set strict demands over its nuclear program and its ballistic missile arsenal, which Tehran insists is crucial for its national defense.

Meanwhile Monday, Iran called for pro-government demonstrators to head to the streets in support of the theocracy, a show of force after days of protests directly challenging the rule of 86-year-old Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Iranian state television aired chants from the crowd, who shouted “Death to America!” and “Death to Israel!”

Trump and his national security team have been weighing a range of potential responses against Iran including cyberattacks and direct strikes by the U.S. or Israel, according to two people familiar with internal White House discussions who were not authorized to comment publicly and spoke on condition of anonymity.

“The military is looking at it, and we’re looking at some very strong options,” Trump told reporters on Air Force One on Sunday night. Asked about Iran’s threats of retaliation, he said: “If they do that, we will hit them at levels that they’ve never been hit before.”

Trump said that his administration was in talks to set up a meeting with Tehran, but cautioned that he may have to act first as reports of the death toll in Iran mount and the government continues to arrest protesters.

“I think they’re tired of being beat up by the United States,” Trump said. “Iran wants to negotiate.”

He added: “The meeting is being set up, but we may have to act because of what’s happening before the meeting. But a meeting is being set up. Iran called, they want to negotiate.”

Iran through country's parliamentary speaker warned Sunday that the U.S. military and Israel would be “legitimate targets” if America uses force to protect demonstrators.

More than 10,600 people also have been detained over the two weeks of protests, said the U.S.-based Human Rights Activists News Agency, which has been accurate in previous unrest in recent years and gave the death toll. It relies on supporters in Iran crosschecking information. It said 496 of the dead were protesters and 48 were with security forces.

With the internet down in Iran and phone lines cut off, gauging the demonstrations from abroad has grown more difficult. The Associated Press has been unable to independently assess the toll. Iran’s government has not offered overall casualty figures.

Those abroad fear the information blackout is emboldening hard-liners within Iran’s security services to launch a bloody crackdown. Protesters flooded the streets in the country’s capital and its second-largest city on Saturday night into Sunday morning. Online videos purported to show more demonstrations Sunday night into Monday, with a Tehran official acknowledging them in state media.

In Tehran, a witness told the AP that the streets of the capital empty at the sunset call to prayers each night. By the Isha, or nighttime prayer, the streets are deserted.

Part of that stems from the fear of getting caught in the crackdown. Police sent the public a text message that warned: “Given the presence of terrorist groups and armed individuals in some gatherings last night and their plans to cause death, and the firm decision to not tolerate any appeasement and to deal decisively with the rioters, families are strongly advised to take care of their youth and teenagers.”

Another text, which claimed to come from the intelligence arm of the paramilitary Revolutionary Guard, also directly warned people not to take part in demonstrations.

“Dear parents, in view of the enemy’s plan to increase the level of naked violence and the decision to kill people, ... refrain from being on the streets and gathering in places involved in violence, and inform your children about the consequences of cooperating with terrorist mercenaries, which is an example of treason against the country,” the text warned.

The witness spoke to the AP on condition of anonymity due to the ongoing crackdown.

The demonstrations began Dec. 28 over the collapse of the Iranian rial currency, which trades at over 1.4 million to $1, as the country’s economy is squeezed by international sanctions in part levied over its nuclear program. The protests intensified and grew into calls directly challenging Iran’s theocracy.

Nikhinson reported from aboard Air Force One.

In this frame grab from video obtained by the AP outside Iran, a masked demonstrator holds a picture of Iran's Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi during a protest in Tehran, Iran, Friday, January. 9, 2026. (UGC via AP)

In this frame grab from footage circulating on social media from Iran shows protesters taking to the streets despite an intensifying crackdown as the Islamic Republic remains cut off from the rest of the world in Tehran, Iran, Friday, Jan. 9, 2026.(UGC via AP)

In this frame grab from footage circulating on social media from Iran showed protesters once again taking to the streets of Tehran despite an intensifying crackdown as the Islamic Republic remains cut off from the rest of the world in Tehran, Iran, Saturday Jan. 10, 2026. (UGC via AP)