MADRID (AP) — While Europe’s military heavyweights have already said that meeting President Donald Trump’s potential challenge to spend up to 5% of their economic output on security won't be easy, it would be an especially tall order for Spain.

The eurozone’s fourth-largest economy, Spain ranked last in the 32-nation military alliance last year for the share of its GDP that it contributed to the military, estimated to be 1.28%. That’s after NATO members pledged in 2014 to spend at least 2% of GDP on defense — a target that 23 countries were belatedly expected to meet last year amid concerns about the war in Ukraine.

When pressed, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez and others in his government have emphasized Spain’s commitment to European security and to NATO. Since 2018, Spain has increased its defense spending by about 50% from 8.5 billion euros ($8.9 billion) to 12.8 billion euros ($13.3 billion) in 2023. Following years of underinvestment, the Sánchez government says the spending increase is proof of the commitment Spain made to hit NATO’s 2% target by 2029.

But for Spain to spend even more — and faster — would be tough, defense analysts and former officials say, largely because of the unpopular politics of militarism in the Southern European nation. The country’s history of dictatorship and its distance from Europe’s eastern flank also play a role.

“The truth is defense spending is not popular in European countries, whether it’s Spain or another European country,” said Nicolás Pascual de la Parte, a former Spanish ambassador to NATO who is currently a member of European Parliament from Spain’s conservative Popular Party. “We grew accustomed after the Second World War to delegate our ultimate defense to the United States of America through its military umbrella, and specifically its nuclear umbrella."

“It's true that we need to spend more,” Pascual de la Parte said of Spain.

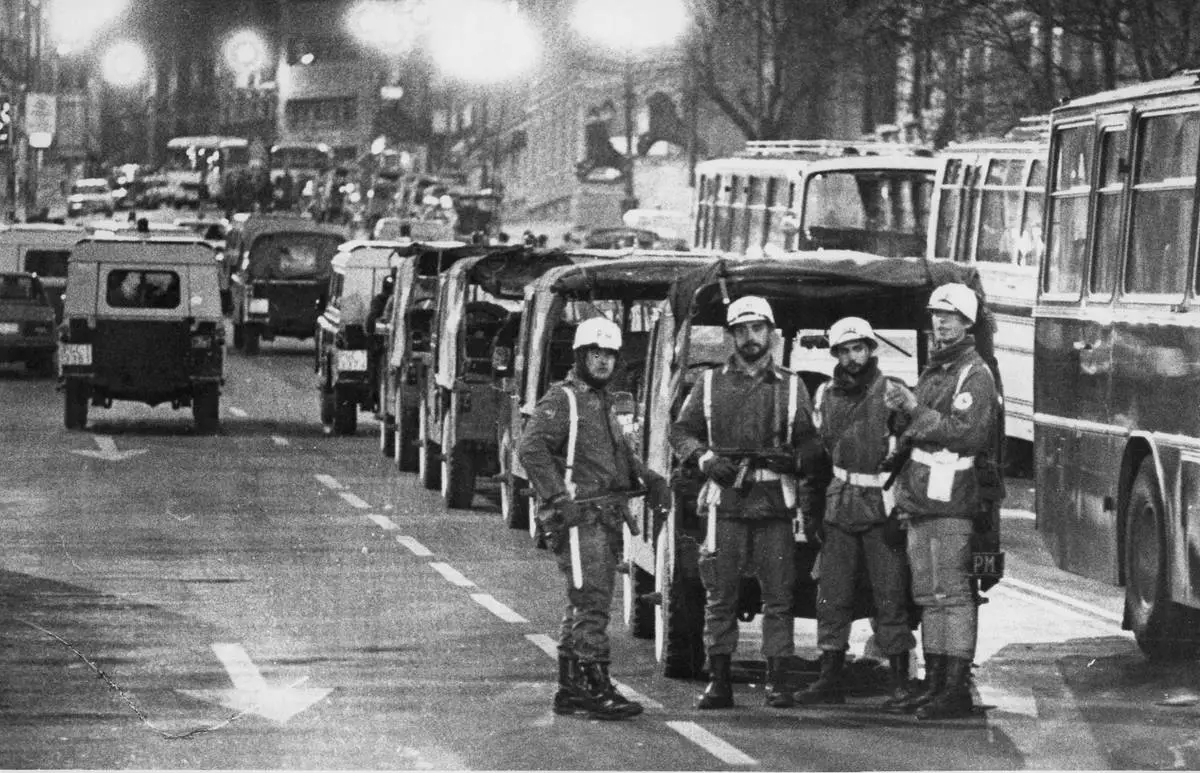

Spain joined NATO in 1982, a year after the young, isolated democracy survived a coup attempt by its armed forces and seven years after the end of the 40-year military dictatorship led by Gen. Francisco Franco. Under a 1986 referendum, a narrow majority of Spaniards voted to stay in the alliance, but it wasn’t until 1999 that the country that is now Europe’s fourth-largest by population joined NATO’s military structure.

In that sense, “we are a very young member of NATO,” said Carlota Encina, a defense and security analyst at the Elcano Royal Institute think tank in Madrid.

Opinion polls generally show military engagement as unpopular among Spanish voters. An overwhelming majority of Spaniards were opposed to their country’s involvement in the 2003 Iraq war, polls showed at the time, but support for NATO in recent years has grown.

About 70% of Spaniards were in favor of NATO sending military equipment, weapons and ammunition to Ukraine soon after Russia began its full-scale invasion of the country, according to a March 2022 poll conducted by the state-owned Centre for Sociological Studies, or CIS. But only about half were in favor of Spain increasing its own defense budget, according to another survey CIS conducted that month.

Across the spectrum, political analysts and former Spanish politicians say militarism just isn’t great politics. Madrid is nearly 3,000 kilometers (roughly 1,800 miles) west of Kiev, unlike the capitals of Poland, Estonia or Latvia, which are closer and have exceeded the alliance's 2% target based on last year’s estimates.

Ignasi Guardans, a Spanish former member of the European Union’s parliament, said many Spaniards value their army for humanitarian efforts and aid work, like the help thousands of soldiers provided after the destructive Valencia flash floods last year.

“Now the army has returned to have some respect,” Guardans said, “but that’s not NATO.”

Encina said Spanish politicians generally feel much more pressure to spend publicly on other issues. “This is something that politicians here always feel and fear,” she said. The thinking goes, “why do we need to invest in defense and not in social issues?”

Spain’s leaders point out that while they have yet to meet NATO’s budget floor, it’s unfair to only consider the country’s NATO contributions as a percentage of GDP to measure of its commitments to Europe and its own security.

Officials often point to the country’s various EU and U.N. missions and deployments, arguing that through them, the country contributes in good form.

“Spain, as a member of NATO, is a serious, trustworthy, responsible and committed ally,” Defense Minister Margarita Robles told reporters this week following comments made by Trump to a journalist who asked the U.S. president about NATO’s low spenders. “And at this moment, we have more than 3,800 men and women in peace missions, many of them with NATO,” Robles said.

Spain’s armed forces are deployed in 16 overseas missions, according to the defense ministry, with ground forces taking part in NATO missions in Latvia, Slovakia and Romania and close to 700 soldiers in Lebanon as part of the country’s largest U.N. mission.

Spain also shares the Morón and Rota naval bases in the south of the country with the U.S. Navy, which stations six AEGIS destroyers at the Rota base in Cádiz.

Analysts also point to the fact that Spain’s government routinely spends more on defense than what is budgeted, through extraordinary contributions that can exceed the official budget during some years by 20% to 30%.

“The reality is, the whole thing is not very transparent,” Guardans said.

Pascual de la Parte, who was Spain’s NATO ambassador from 2017 to 2018, said the 2% metric shouldn’t be the only measure since not every NATO member accounts for their defense budgets in the same way.

“There is no agreement between allies in choosing which criteria decide the real spending effort,” he said, adding that, for example, while some countries include things like soldiers’ pensions in their accounting, others don’t. “Ultimately, they can involve very disparate realities.”

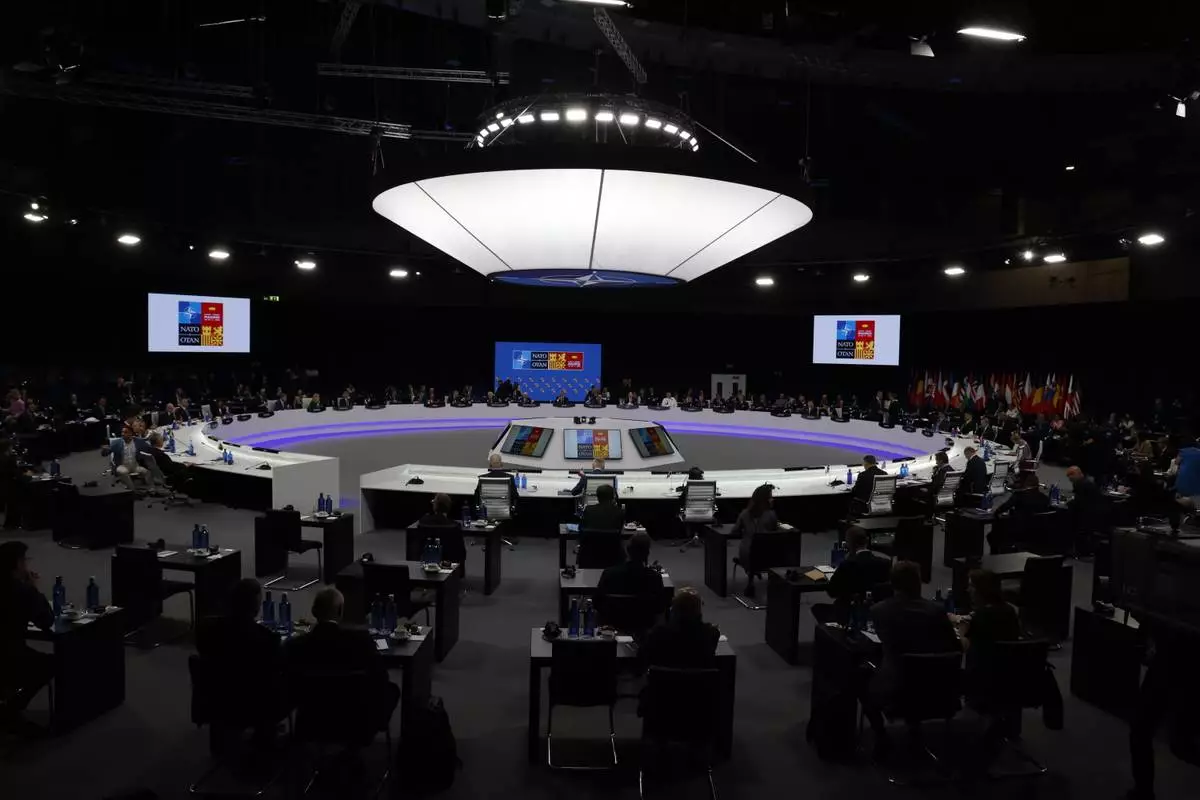

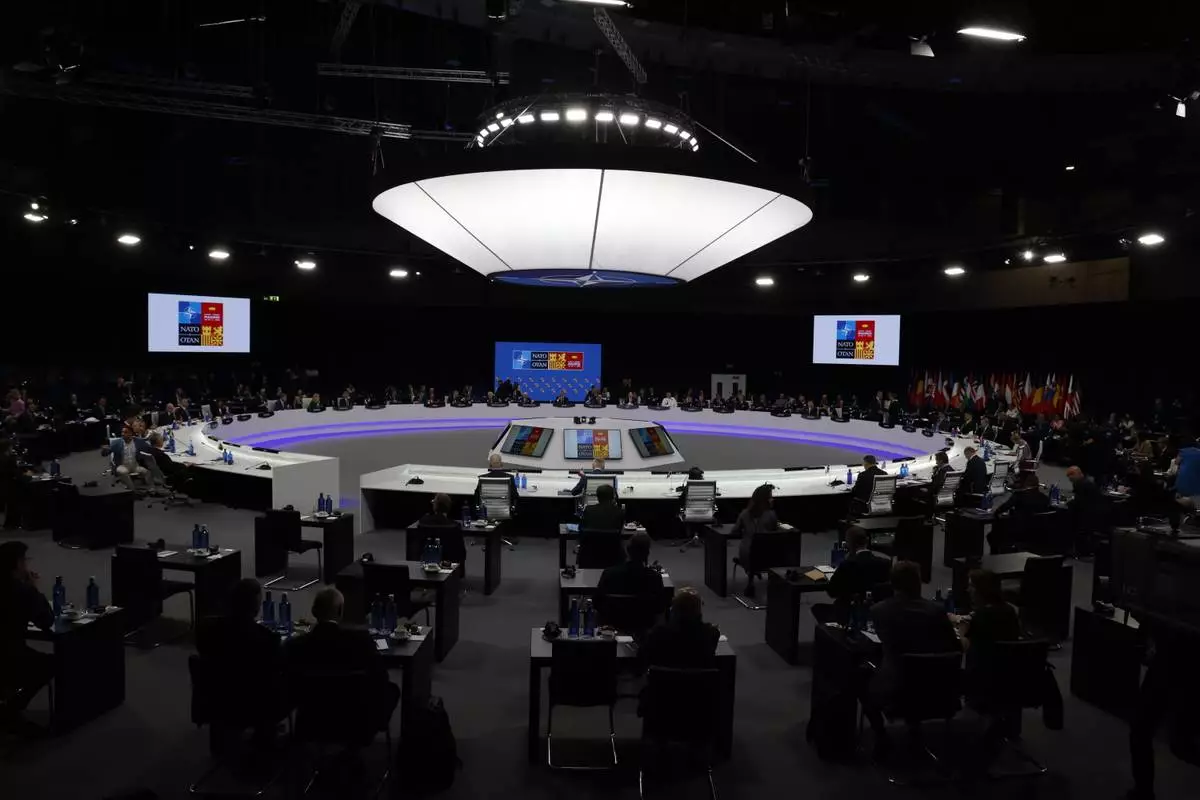

FILE - A general view of the Meeting of the North Atlantic Council Session with fellow heads of state at the NATO summit at the IFEMA arena in Madrid, on June 30, 2022. (Jonathan Ernst/Pool Photo via AP, File)

FILE - Bulgarian and Spanish Air Forces'personnel pose in front of Eurofighter EF-2000 Typhoon II aircraft and MiG-29, in Graf Ignatievo, Feb. 17, 2022. (AP Photo/Valentina Petrova, file)

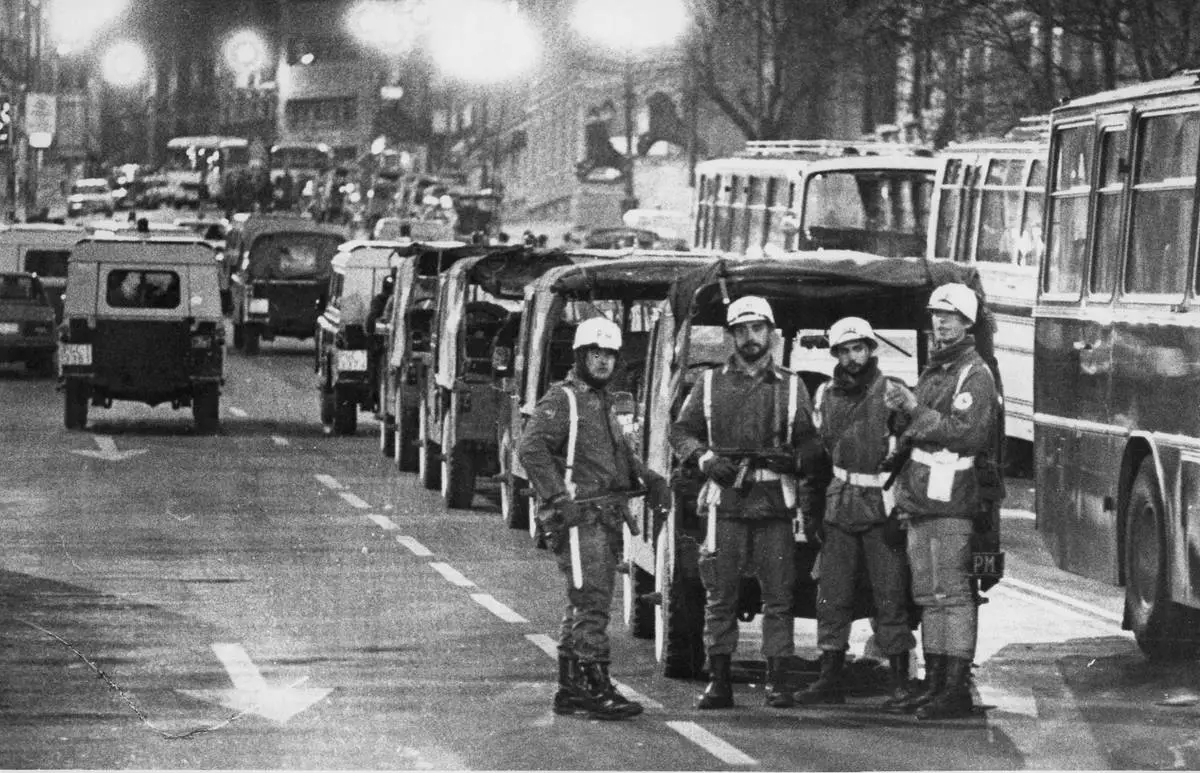

FILE - Armed Spanish military police are seen on duty at the square in front of the Spanish Cortes (Parliament) seen in the background, in Madrid, Feb. 24, 1981 while inside the lower house about 150 armed Civil Guards still hold the deputies hostage. (AP Photo)

A group of Buddhist monks and their rescue dog are striding single file down country roads and highways across the South, captivating Americans nationwide and inspiring droves of locals to greet them along their route.

In their flowing saffron and ocher robes, the men are walking for peace. It's a meditative tradition more common in South Asian countries, and it's resonating now in the U.S., seemingly as a welcome respite from the conflict, trauma and politics dividing the nation.

Their journey began Oct. 26, 2025, at a Vietnamese Buddhist temple in Texas, and is scheduled to end in mid-February in Washington, D.C., where they will ask Congress to recognize Buddha’s day of birth and enlightenment as a federal holiday. Beyond promoting peace, their highest priority is connecting with people along the way.

“My hope is, when this walk ends, the people we met will continue practicing mindfulness and find peace,” said the Venerable Bhikkhu Pannakara, the group’s soft-spoken leader who is making the trek barefoot. He teaches about mindfulness, forgiveness and healing at every stop.

Preferring to sleep each night in tents pitched outdoors, the monks have been surprised to see their message transcend ideologies, drawing huge crowds into churchyards, city halls and town squares across six states. Documenting their journey on social media, they — and their dog, Aloka — have racked up millions of followers online. On Saturday, thousands thronged in Columbia, South Carolina, where the monks chanted on the steps of the State House and received a proclamation from the city's mayor, Daniel Rickenmann.

At their stop Thursday in Saluda, South Carolina, Audrie Pearce joined the crowd lining Main Street. She had driven four hours from her village of Little River, and teared up as Pannakara handed her a flower.

“There’s something traumatic and heart-wrenching happening in our country every day,” said Pearce, who describes herself as spiritual, but not religious. “I looked into their eyes and I saw peace. They’re putting their bodies through such physical torture and yet they radiate peace.”

Hailing from Theravada Buddhist monasteries across the globe, the 19 monks began their 2,300 mile (3,700 kilometer) trek at the Huong Dao Vipassana Bhavana Center in Fort Worth.

Their journey has not been without peril. On Nov. 19, as the monks were walking along U.S. Highway 90 near Dayton, Texas, their escort vehicle was hit by a distracted truck driver, injuring two monks. One of them lost his leg, reducing the group to 18.

This is Pannakara's first trek in the U.S., but he's walked across several South Asian countries, including a 112-day journey across India in 2022 where he first encountered Aloka, an Indian Pariah dog whose name means divine light in Sanskrit.

Then a stray, the dog followed him and other monks from Kolkata in eastern India all the way to the Nepal border. At one point, he fell critically ill and Pannakara scooped him up in his arms and cared for him until he recovered. Now, Aloka inspires him to keep going when he feels like giving up.

“I named him light because I want him to find the light of wisdom,” Pannakara said.

The monk's feet are now heavily bandaged because he's stepped on rocks, nails and glass along the way. His practice of mindfulness keeps him joyful despite the pain from these injuries, he said.

Still, traversing the southeast United States has presented unique challenges, and pounding pavement day after day has been brutal.

“In India, we can do shortcuts through paddy fields and farms, but we can’t do that here because there are a lot of private properties,” Pannakara said. “But what’s made it beautiful is how people have welcomed and hosted us in spite of not knowing who we are and what we believe.”

In Opelika, Alabama, the Rev. Patrick Hitchman-Craig hosted the monks on Christmas night at his United Methodist congregation.

He expected to see a small crowd, but about 1,000 people showed up, creating the feel of a block party. The monks seemed like the Magi, he said, appearing on Christ’s birthday.

“Anyone who is working for peace in the world in a way that is public and sacrificial is standing close to the heart of Jesus, whether or not they share our tradition,” said Hitchman-Craig. “I was blown away by the number of people and the diversity of who showed up.”

After their night on the church lawn, the monks arrived the next afternoon at the Collins Farm in Cusseta, Alabama. Judy Collins Allen, whose father and brother run the farm, said about 200 people came to meet the monks — the biggest gathering she’s ever witnessed there.

“There was a calm, warmth and sense of community among people who had not met each other before and that was so special,” she said.

Long Si Dong, a spokesperson for the Fort Worth temple, said the monks, when they arrive in Washington, plan to seek recognition of Vesak, the day which marks the birth and enlightenment of the Buddha, as a national holiday.

“Doing so would acknowledge Vesak as a day of reflection, compassion and unity for all people regardless of faith,” he said.

But Pannakara emphasized that their main goal is to help people achieve peace in their lives. The trek is also a separate endeavor from a $200 million campaign to build towering monuments on the temple’s 14-acre property to house the Buddha’s teachings engraved in stone, according to Dong.

The monks practice and teach Vipassana meditation, an ancient Indian technique taught by the Buddha himself as core for attaining enlightenment. It focuses on the mind-body connection — observing breath and physical sensations to understand reality, impermanence and suffering. Some of the monks, including Pannakara, walk barefoot to feel the ground directly and be present in the moment.

Pannakara has told the gathered crowds that they don't aim to convert people to Buddhism.

Brooke Schedneck, professor of religion at Rhodes College in Memphis, Tennessee, said the tradition of a peace walk in Theravada Buddhism began in the 1990s when the Venerable Maha Ghosananda, a Cambodian monk, led marches across war-torn areas riddled with landmines to foster national healing after civil war and genocide in his country.

“These walks really inspire people and inspire faith,” Schedneck said. “The core intention is to have others watch and be inspired, not so much through words, but through how they are willing to make this sacrifice by walking and being visible.”

On Thursday, Becki Gable drove nearly 400 miles (about 640 kilometers) from Cullman, Alabama, to catch up with them in Saluda. Raised Methodist, Gable said she wanted some release from the pain of losing her daughter and parents.

“I just felt in my heart that this would help me have peace,” she said. “Maybe I could move a little bit forward in my life.”

Gable says she has already taken one of Pannakara’s teachings to heart. She’s promised herself that each morning, as soon as she awakes, she’d take a piece of paper and write five words on it, just as the monk prescribed.

“Today is my peaceful day.”

Freelance photojournalist Allison Joyce contributed to this report.

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

Buddhist monks who are participating in the, "Walk For Peace," get lunch Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Aloka rests with Buddhist monks who are participating in the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

A sign is seen greeting the Buddhist monks who are participating in the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Supporters pray with Buddhist monks who are participating in the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Supporters watch Buddhist monks who are participating in the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

A Buddhist monk ties a prayer bracelet around the wrist of Josey Lee, 2-months-old, during the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Bhikkhu Pannakara, a spiritual leader, speaks to supporters during the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Buddhist monks participate in the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Buddhist monks participate in the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Bhikkhu Pannakara leads other buddhist monks in the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Audrie Pearce greets Buddhist monks who are participating in the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Bhikkhu Pannakara, a spiritual leader, speaks to supporters during the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Buddhist monks who are participating in the, "Walk For Peace," arrive in Saluda, Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Buddhist monks who are participating in the, "Walk For Peace," are seen with their dog, Aloka, Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)