MILWAUKEE (AP) — As the candidates for a Wisconsin Supreme Court seat squared off in a recent debate before early voting, one issue came up first and dominated at the start.

“Let’s talk about abortion rights,” the moderator said.

The winner of the April 1 election could hold the power to determine the fate of any future litigation over abortion because the outcome of the race for a vacancy on the state's highest court will decide whether liberals or conservatives hold a majority.

Abortion has become a central plank of the platform for the Democratic-backed candidate, Dane County Judge Susan Crawford, in part because of its effect on voter turnout, although to a lesser extent than during a heated 2023 state Supreme Court race that flipped the court to a liberal majority. Brad Schimel, a former state attorney general, is the Republican-supported candidate.

“Abortion of course remains a top issue,” said Charles Franklin, a Marquette University political scientist. “But we haven’t seen either candidate be as outspoken on hot-button issues as we saw in 2023.”

Democrats are hoping voters will be motivated by the potential revival of an abortion ban from 1849, which criminalizes “the willful killing of an unborn quick child.” The Wisconsin Supreme Court is currently deciding whether to reactivate the 175-year-old ban.

Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin filed a separate lawsuit in February asking the court to rule on whether a constitutional right to abortion exists in the state.

The 19th century law was enacted just a year after Wisconsin became a state, when lead mining and the lumber industry formed the bedrock of the state’s economy as white settlers rushed into areas left vacant by forced removals of Native American tribes.

It also was a time when combinations of herbs stimulating uterine contractions were the most common abortion method, said Kimberly Reilly, a history and gender studies professor at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay.

“During this time, there were no women in statehouses,” Reilly said. “When a woman got married, she lost her legal identity. Her husband became her legal representative. She couldn’t own property in her name. She couldn’t make a contract.”

This is the latest instance of long-dormant restrictions influencing current abortion policies after the U.S. Supreme Court in 2022 overturned Roe v. Wade, which had granted a federal right to abortion.

The revival of an 1864 Arizona abortion law, enacted when Arizona was a territory, sparked a national outcry last year. Century-old abortion restrictions passed by all-male legislatures during periods when women could not vote — and scientific knowledge of pregnancy and abortion were limited — have also influenced post-Roe abortion policies in Alabama, Arkansas, Michigan, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Texas and West Virginia.

Those laws tend to be more severe. They often do not include exceptions for rape and incest, call for the imprisonment of providers and ban the procedure in the first few weeks of pregnancy. Some have since been repealed, while others are being challenged in court.

During the state Supreme Court debate March 12, Crawford declined to weigh in directly on the 1849 abortion case but promoted her experience representing Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin and “making sure that women could make their own choices about their bodies and their health care.” In an ad released Wednesday, she accused Schimel of not trusting “women to make their own healthcare decisions.”

Schimel calls himself “pro-life” and has previously supported leaving Wisconsin’s 1849 abortion ban on the books. He dodged questions about abortion during the debate, saying he believes the issue should be left up to voters, although Wisconsin does not have a citizen-led ballot initiative process, which voters in several other states have used to protect abortion rights.

Anthony Chergosky, a University of Wisconsin-La Crosse political scientist, said Schimel has been “borrowing from the Republican playbook of avoiding the issue of abortion” by leaving the question to voters in individual states.

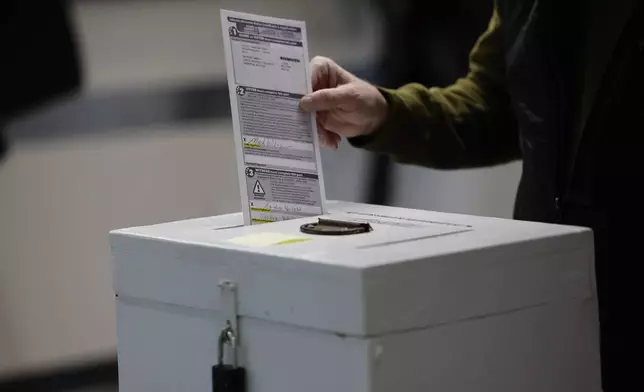

The message has still gotten across to many Democratic voters, who cited abortion as a top issue while waiting in line for early voting this past week.

Jane Delzer, a 75-year-old liberal voter in Waukesha, said “a woman’s right to choose is my biggest motivator. I’m deeply worried about what Schimel may do on abortion.”

June Behrens, a 79-year-old retired teacher, spoke about a loved one’s abortion experience: “Everyone makes their own choice and has their own journey in life, and they deserve that right.”

Republican voters primarily cited immigration and the economy as their top issues, essentially the same ones that helped propel Republican Donald Trump's win over Democratic Vice President Kamala Harris last November in the presidential election. But others said they also wanted conservative social views reflected on the court.

Lewis Titus, a 72-year-old volunteer for the city of Eau Claire, said restricting abortion was his top issue in the Supreme Court race: "I believe that Brad Schimel is the one to carry that on.”

While it's one of the key issues this year, abortion played a much larger role two years ago, when a race for Wisconsin’s highest court demonstrated how expensive and nationalized state Supreme Court races have become.

This year’s campaigns have focused primarily on “criminal sentencing and attempting to paint one another as soft on crime,” said Howard Schweber, a University of Wisconsin-Madison political science professor emeritus.

Crawford also has tried to make the race a referendum on Trump after his first months in office and tech billionaire Elon Musk, who is running Trump’s massive federal cost-cutting initiative and has funded two groups that have together spent more than $10 million to promote Schimel.

“Two years ago, abortion was a hugely mobilizing issue, and we saw that clearly in the lead-up to the election,” Schweber said. “We’re seeing some of this but not to the same extent, which really makes no sense. The issues and stakes are exactly the same.”

The decision to elevate other issues might be the result of anxiety among Democrats that abortion may not resonate as deeply as they once believed after significant election losses in November, despite Harris using abortion as a pillar of her campaign, several Wisconsin politics experts said.

Franklin, the political scientist, said he believes abortion will motivate Democrats, but the issue may not rank high in the priorities of independent voters, who he says will be central to the race's outcome.

“In the early days after Roe v. Wade was overturned, it was still a very hot issue for voters,” he said. “But as states have codified their abortion laws, the issue doesn’t seem to motivate voters to the same extent. In the fall, many Democrats believed abortion was still this magic silver bullet and would win them the presidential and Senate races. But the outcomes didn’t seem to support that.”

Associated Press video journalist Mark Vancleave in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, contributed to this report.

The Associated Press receives support from several private foundations to enhance its explanatory coverage of elections and democracy. See more about AP’s democracy initiative here. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Wisconsin Supreme Court candidates Brad Schimel and Susan Crawford are seen before a debate Wednesday, March 12, 2025, in Milwaukee. (AP Photo/Morry Gash)

A voter casts a ballot during early voting in Waukesha, Wis., Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeffrey Phelps)

People cast their ballots during early voting in Waukesha, Wis., Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeffrey Phelps)

A voter casts a ballot during early voting in Waukesha, Wis., Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeffrey Phelps)

A sign along a street in Milwaukee, Wis., Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeffrey Phelps)

Wisconsin Supreme Court candidates Brad Schimel and Susan Crawford participate in a debate Wednesday, March 12, 2025, in Milwaukee. (AP Photo/Morry Gash)

A man places his ballot in a box during early voting in Waukesha, Wis Tuesday, March 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Jeffrey Phelps)

Wisconsin Supreme Court candidates Brad Schimel and Susan Crawford participate in a debate Wednesday, March 12, 2025, in Milwaukee. (AP Photo/Morry Gash)

Wisconsin Supreme Court candidates Brad Schimel and Susan Crawford participate in a debate Wednesday, March 12, 2025, in Milwaukee. (AP Photo/Morry Gash)