BUENOS AIRES, Argentina (AP) — President Javier Milei on Friday announced that he would lift most of the country’s strict capital and currency controls next week, a high-stakes gamble made possible by a new loan from the International Monetary Fund. It marked a major step forward in the libertarian's program to normalize Argentina's economy after decades of unbridled spending.

The IMF’s executive board late Friday green-lit the $20 billion bailout package, which offers a lifeline to Argentina’s dangerously depleting foreign currency reserves over the next four years. The fund praised President Milei's tough austerity program and zero-deficit fiscal policy, saying the program sought to “consolidate impressive initial gains” and address "remaining macroeconomic vulnerabilities.”

“Against this backdrop, the authorities are embarking on a new phase of their stabilization plan,” said IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva, adding that Argentina has committed to doubling down on spending cuts and economic deregulation and transitioning toward a new foreign currency exchange regime.

Shortly afterward, Milei, flanked by his ministers, addressed his nation on television.

“Today we are breaking the cycle of disillusionment and disenchantment and are beginning to move forward for the first time,” he said. “We have eliminated the exchange rate controls on the Argentine economy for good.”

The capital controls, known here as “el cepo,” or “the clamp, ” are a tangle of regulations that help to stabilize the peso at an official rate and prevent capital flight from Argentina.

Imposed by a previous administration in 2019, the restrictions clamp down on individuals’ and companies’ access to dollars, discouraging the foreign investment that Milei needs to achieve his goal of transforming heavily regulated Argentina into a free economy.

The restrictions made it almost impossible for ordinary Argentines to purchase dollars, giving rise to a black market that is technically illegal but that almost every Argentine uses to sell their depreciating pesos anyway. Their removal takes effect on Monday.

The bank said it would receive the first $12 billion from the IMF Tuesday — a bigger-than-expected upfront sum that gives Argentina's reserves breathing room to make the major change and reflects the fund's confidence in Milei's radical reforms.

“The program is unprecedented in supporting an economic plan that has already yielded results,” Milei said.

The new policy also involves cutting the Argentine peso free from its peg to the dollar. But instead of a risky free float, Argentina is allowing the peso to trade within a so-called currency band that ranges from 1,000 to 1,400 pesos per dollar. The band will expand 1% each month, the bank said.

This breaks from Milei's current policy of letting the peso weaken at a pace of 1% against the dollar each month.

That crawling peg had drawn backlash from investors worried about the central bank burning through its reserves to prop up the peso. It was forced to spend $2.5 billion to defend the official exchange rate in just the past few weeks.

When announcing the removal of exchange controls Economy Minister Luis Caputo insisted it was “not a devaluation.”

"The truth is, we don’t know where the dollar will end up,” he said.

Milei’s team has sought to fend off a politically costly official devaluation of the peso that could push inflation much higher. Keeping a lid on rising prices — a flagship campaign promise — has helped the political outsider hold up approval ratings despite his brutal cuts to state spending that might otherwise trigger social unrest.

But it was clear that the peso would have to depreciate to some extent, with economists guessing that it would fall to close to its black-market rate. On Friday, that rate was 1,375 pesos to the dollar, compared with the official exchange rate of 1,097 pesos.

Marcelo J. García, director for the Americas at New York-based geopolitical risk consultancy Horizon Engage, said he expected an initial devaluation of around 20-25%.

“A big question mark is inflation in the second quarter of the year. It’s very likely there will be a shock,” said Leonardo Piazza, chief economist at Argentine consulting firm LP Consulting.

Before Milei took office in December 2023, the previous left-wing Peronist administration ran up massive budget deficits, leading to sky-high inflation and a chronically weakening peso.

By scrapping subsidies and price controls, firing tens of thousands of state workers and halting the central bank's overreliance on printing pesos to pay the government’s bills, Milei has delivered Argentina's first fiscal surplus in almost two decades and largely stabilized its macroeconomic imbalances, thrilling markets even as his overhaul hits the population hard.

Yet for all the changes and the financial pain, there have been scant signs of a sustainable recovery. Analysts say that a long-term economic revival involves the removal of capital controls, the amassing of currency reserves and access to international capital markets.

As a result, foreign investors have waited on the sidelines, wary of pouring their cash into a country infamous for defaulting on its debt.

The South American nation is already the IMF’s biggest debtor, owing some $43 billion. This new $20 billion loan represents the 23rd rescue package in the nation’s long and tumultuous history.

Milei has rejected pressure from investors over the past year to lift the capital controls, insisting that the economic conditions needed to be right. Now, he said, it was finally time.

After the first $12 billion disbursement from the IMF, another $2 billion will hit Argentina’s central bank in the next two months, the fund said.

International organizations will also pitch in, with the Inter-American Development Bank announcing later Friday $10 billion disbursed over the next three years.

“With this level of reserves, we can back up all the existing pesos in our economy, providing monetary security to our citizens,” Milei said. “These are the foundations for sustained, long-term growth.”

It's a high-risk mission, as scrapping the “cepo” could unleash years of pent-up demand for U.S. dollars and spark a currency run as companies try to send their long-trapped profits home.

“It could be a tsunami of money out,” said Christopher Ecclestone, a strategist with investment bank Hallgarten & Company. “It’s a total guessing game as to what people will do.”

The central bank said that while it was lifting restrictions for the public, it would retain taxes on card purchases abroad and some regulations on companies. For instance, from 2025 on, multinational firms will be able to repatriate their earnings. But to get their already trapped holdings out of the country, they'll need to exchange the debt for dollar-denominated security bonds.

It's an effort to insure against capital flight, which would imperil Milei's primary accomplishment of lowering inflation ahead of midterm elections in October that are crucial for his libertarian party to expand its small congressional minority.

“The announcement is more audacious than expected. The government is making a bit of a leap of faith by lifting the cepo,” said García.

It's also bold timing, analysts say, considering the local market turmoil sparked by U.S. President Donald Trump’s tariffs. In recent days, Argentine stocks and bonds have plunged.

Meanwhile, with traders nervous about a possible peso devaluation under Argentina's IMF deal, the closely watched gap between Argentina's currency exchange rates has grown by over 20% in recent weeks. The gap is a key indicator of confidence in the government and can fuel inflation, which already accelerated in March to its fastest pace in seven months.

On Friday, Argentina’s National Statistics Institute reported that consumer prices ticked up 3.7% last month compared to 2.4% in February, mainly as a result of rising food prices.

Mieli was unruffled. “Inflation will disappear,” he promised.

Associated Press writer Almudena Calatrava contributed to this report.

A television screen in a car garage displays a national address by President Javier Milei, accompanied by Cabinet members, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Friday, April 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

A television airs a national message by President Javier Milei, accompanied by members of his Cabinet, at a restaurant in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Friday, April 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

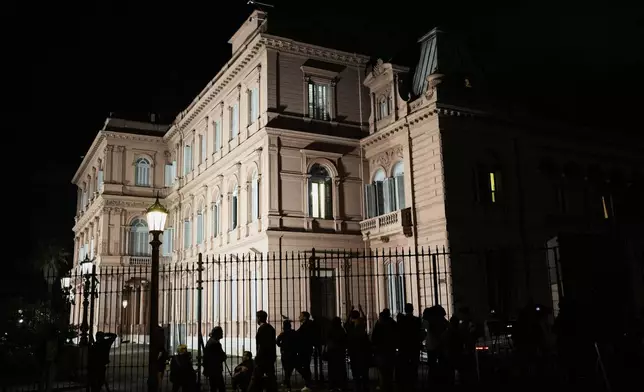

Journalists wait outside Government House where Economy Minister Luis Caputo is holding a conference, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Friday, April 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

FILE - Argentina's President Javier Milei, left, and Economy Minister Luis Caputo attend the Mercosur Summit in Montevideo, Uruguay, Dec. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Matilde Campodonico, File)

A worker pushes a dolly at a butcher in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Monday, March 31, 2025. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)