KUALA LUMPUR, Malaysia (AP) — Former Malaysian Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, a moderate who extended the country’s political freedoms but was criticized for lackluster leadership, has died of heart disease. He was 85.

Affectionately known as “Pak Lah,” or uncle Lah, Abdullah was admitted to Kuala Lumpur’s State Institute of Heart on Sunday after experiencing breathing difficulties. He was closely monitored by a cardiac specialists team, but passed away on Monday at 7:10 p.m. despite all medical efforts, the hospital said in a statement.

Abdullah was first admitted to the hospital in April 2024, after being diagnosed with spontaneous pneumothorax, a collapsed lung that occurs without any apparent cause. In 2022, his son-in-law, Khairy Jamaluddin, disclosed that Abdullah had dementia that was progressively worsening. He said Abdullah had trouble speaking and could not recognize his family.

Abdullah, Malaysia’s fifth leader, served from 2003 to 2009, when he was pressured to resign to take responsibility for the governing coalition’s dismal results in national elections. He kept a low profile after leaving politics.

Abdullah took office in October 2003, riding a wave of popularity after replacing Mahathir Mohamad, a domineering, sharp-tongued leader known for his semi-authoritarian rule during 22 years in office.

A seasoned politician who held many Cabinet positions, Abdullah was handpicked by Mahathir, who believed a soft-spoken, unambitious leader would maintain his policies.

Initially, Abdullah won support with promises of institutional reforms and his brand of moderate Islam. He pledged greater political freedoms with more space for critics, and vowed to end corruption after a government minister was hauled to court on graft allegations.

“During his rule, the country transitioned from a very authoritarian rule under Mahathir to a more multifaceted regime. It provided some breathing space for many Malaysians after more than two decades of very suffocating rule,” said Oh Ei Sun from Singapore’s Institute of International Affairs.

Months after taking office, Abdullah led his National Front governing coalition to a landslide victory in a 2004 general election seen as a stamp of approval of his leadership. That helped him partially step out of Mahathir’s shadow, but the euphoria didn’t last.

In the following years, Abdullah faced criticism inside and outside his party for generally lackluster and ineffectual leadership. He didn’t follow through on promises to eradicate corruption, reform the judiciary and strengthen institutions such as the police and the civil service.

Critics slammed Abdullah for concurrently taking on the finance minister and internal security minister posts. He was often criticized for dozing off during meetings or at public events, which he blamed on a sleep disorder. Khairy, his son-in-law, led a team of advisers in the Prime Minister’s Office whom critics said influenced Abdullah’s decisions and controlled access to him.

Abdullah also fell out with Mahathir after he axed some of the former leader’s projects, including a proposed bridge to Singapore. Mahathir turned into one of his fiercest critics and accused Abdullah of nepotism and inefficiency..

While Abdullah was viewed as a weak leader, he ushered in limited freedom of speech and allowing a more critical media. Conservatives in his party said that was his undoing as it bolstered a newly resurgent opposition led by reformist Anwar Ibrahim. Anwar, Malaysia’s current leader, became prime minister after 2022 elections.

In late 2007, Abdullah faced a series of massive street protests on issues including fuel hikes, demands for electoral reforms and fairer treatment for ethnic minorities. The protests shook his administration. Police cracked down on the rallies and Abdullah warned he would sacrifice public freedoms for stability.

In the March 2008 general election, his National Front suffered one of its worst results in a huge blow to Abdullah. It failed to secure a two-thirds legislative majority for the first time in 40 years, yielding 82 seats to the opposition in the 222-member Parliament. It also lost an unprecedented five states.

Abdullah initially refused to step down, but pressure grew. Mahathir quit the United Malays National Organization, the linchpin of the governing coalition, to protest Abdullah’s leadership. Dissidents within UMNO openly called on him to resign to take responsibility for the dismal election performance.

Abdullah caved in and handed over power to his deputy, Najib Razak, in April 2009.

Born in the northern state of Penang on Nov. 26, 1939, Abdullah came from a religious family. His grandfather was the first mufti, or Islamic jurist, of Penang. Abdullah received a bachelor’s degree in Islamic Studies from the University of Malaya.

After graduating, he entered the civil service for 14 years before resigning in 1978 to become a member of parliament. During a bitter dispute within UMNO in the 1980s, Abdullah sided with a group that opposed Mahathir. After Mahathir prevailed, Abdullah was sacked as defense minister but was later brought back into the Cabinet as foreign minister in 1991.

In January 1999, Abdullah was appointed deputy prime minister and home affairs minister before succeeding Mahathir as prime minister in 2003.

Abdullah’s first wife, Endon Mahmood, died in 2005 after a battle with breast cancer. They have two children and seven grandchildren. He remarried two years later to Jeanne Abdullah, who was earlier married to the brother of Abdullah’s first wife. She has two children from her previous marriage.

FILE - Malaysia's Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, right, delivers his keynote address United Malays National Organization (UMNO) annual general assembly in Kuala Lumpur, Thursday, March 26, 2009. (AP Photo/Vincent Thian, File)

FILE - Malaysia's Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, right, inspects the members of youth wing of United Malays National Organization during the UMNO general meeting in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Thursday, Sept. 23, 2004. (AP Photo/Vincent Thian, File)

FILE - Malaysian Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, left, gestures as his wife Endon Mahmood looks on after casting their votes during the general election at a polling center in Kepala Batas, northern Malaysia, March 21, 2004. (AP Photo/Andy Wong, File)

FILE - Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao, left, sits next to Malaysia's Prime Minister Adbullah Ahmad Badawi during the Kuala Lumpur Declaration on the ASEAN+3 Summit at the Kuala Lumpur Convention Center in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Monday, Dec. 12, 2005. (AP Photo/Vincent Thian, File)

FILE - Malaysian outgoing Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, also Defence Minister, center, looks on during a farewell ceremony organised by the Defence Ministry in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Thursday, April 2, 2009. (AP Photo/Lai Seng Sin, File)

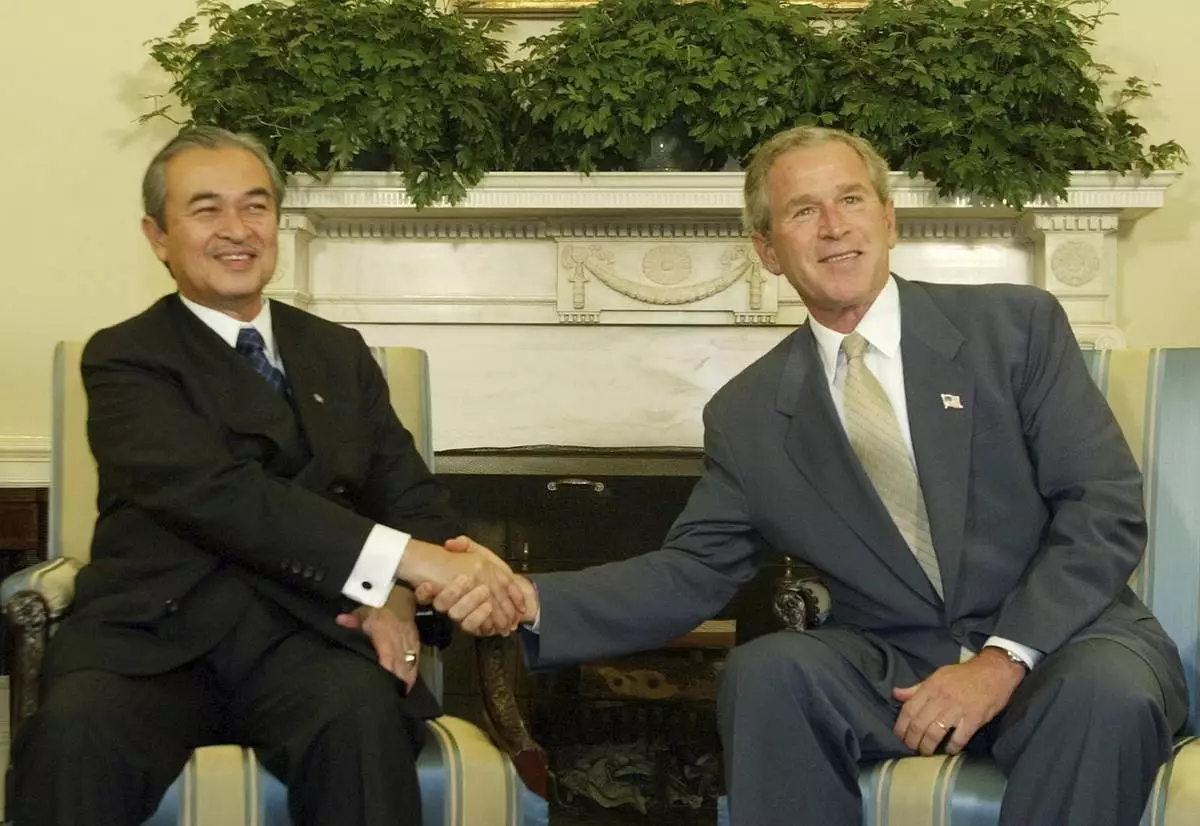

FILE - President George W. Bush, right, greets Malaysian Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi in the Oval Office of the White House, Monday, July 19, 2004, in Washington. (AP Photo/Pablo Martinez Monsivais, File)

FILE - Malaysia's former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, center, raises hands with then Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, right, and then Deputy Prime Minister Najib Razak at the United Malays National Organization (UMNO) general assembly in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, March 28, 2009. (AP Photo/Lai Seng Sin, File)

FILE - Malaysia's former Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, left, waves as new Prime Minister Najib Razak smile behind at Prime Minister office in Putrajaya, April 3, 2009. (AP Photo/Vincent Thian, File)

FILE - Malaysian former Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, center, waves as he leaves prime minister's office in Putrajaya, outside Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Friday, April 3, 2009. (AP Photo/Lai Seng Sin, File)

FILE - Malaysian outgoing Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, also Defense Minister, waves during a farewell ceremony in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Thursday, April 2, 2009. (AP Photo/Lai Seng Sin, File)