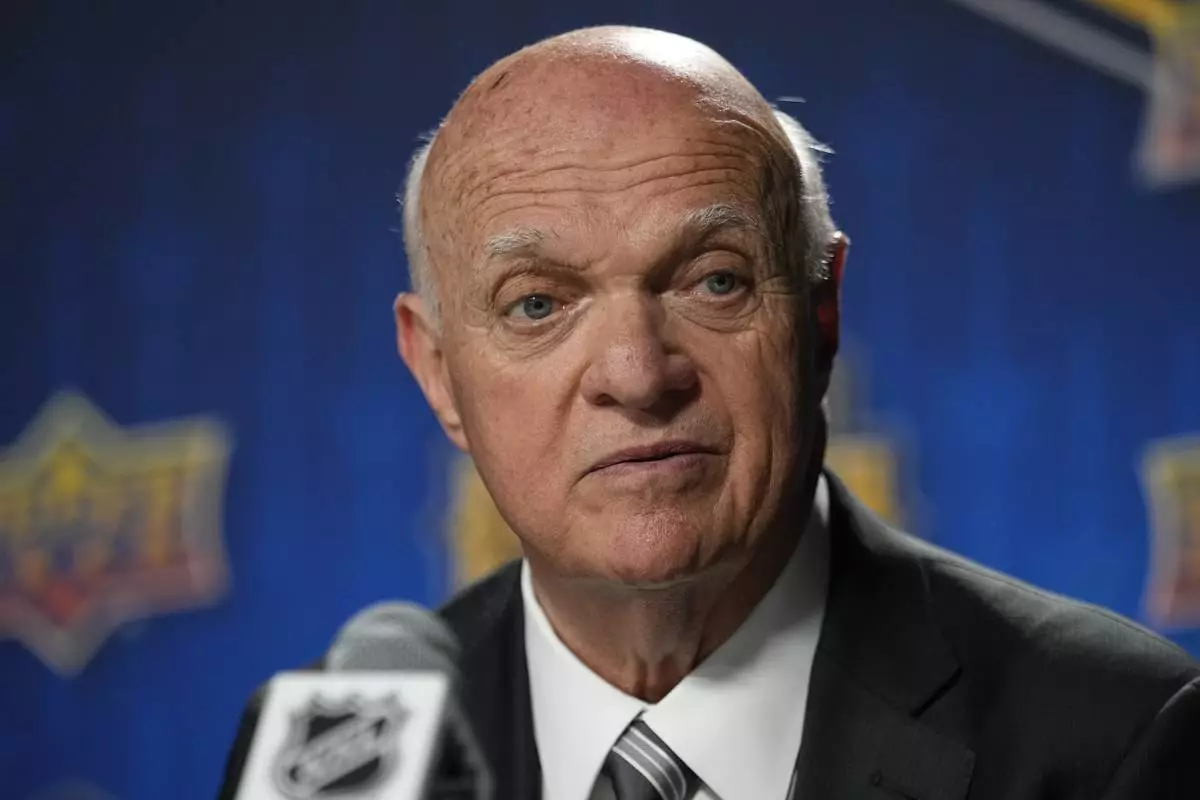

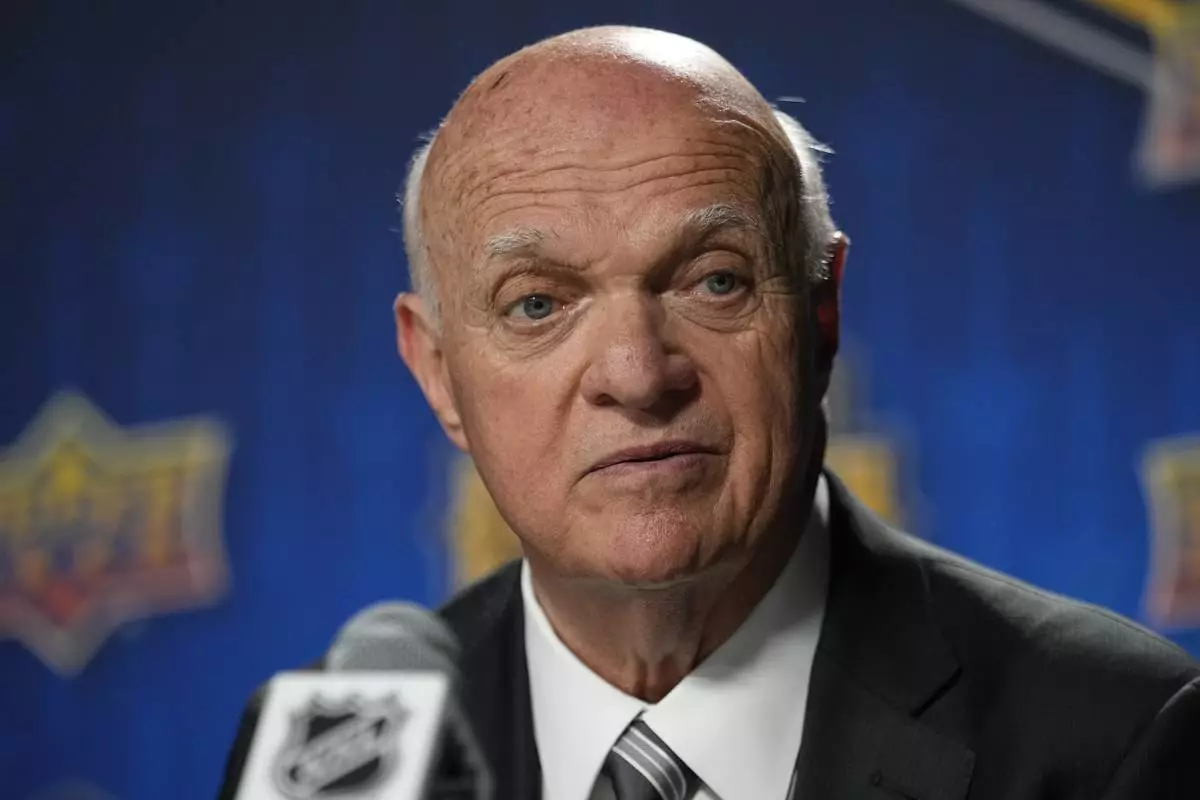

Lou Lamoriello is out as president and general manager of the New York Islanders, after the team said Tuesday the longtime NHL executive’s contract was not being renewed.

Managing partner John Collins will lead a search to find the Islanders’ next GM.

“The Islanders extend a heartfelt thank you to Lou Lamoriello for his extraordinary commitment over the past seven years,” the team said in a statement. “His dedication to the team is in line with his Hall of Fame career.”

Lamoriello, 82, spent the past seven years running the Islanders' hockey operations with a close connection to ownership. They missed the playoffs this season but qualified five times under Lamoriello's watch, including a trip to the Eastern Conference final in the 2020 “bubble” during the coronavirus pandemic.

For the bulk of his time in the league, Lamoriello worked as president and GM of the New Jersey Devils from 1987-2015, a stretch during which they won the Stanley Cup three times. He served as GM of the Toronto Maple Leafs from 2015 until he joined the Islanders in 2018.

A Hall of Famer in the builders category, Lamoriello’s old-school approach with everything from not sharing information to banning facial hair for players and coaches made him a rarity in modern hockey and arguably played a part in stagnating the once widely successful franchise. It is now more than four decades removed from the dynasty days when the Islanders won the Cup four years in a row from 1980-83.

Moving on from Lamoriello puts the entire organization in flux, including the future of the rest of the front office and coaching staff. Lamoriello hired Patrick Roy as coach in January 2024 to replace Lane Lambert.

Son Chris Lamoriello has worked for the Islanders since 2016, originally as director of player personnel, and was promoted to assistant GM to work for his father in 2018.

Agent Dan Milstein called Lou Lamoriello “one of the greatest minds and most respected leaders our sport has ever known."

“It’s been an absolute privilege to work with him over the years,” Milstein wrote in a social media post. “His impact on the game — and on all of us who’ve had the honor to work with and sometimes against him — goes far beyond wins and losses. He brought professionalism, discipline and integrity to everything he touched. (He is) a true legend whose legacy will stand the test of time.”

AP NHL: https://apnews.com/hub/nhl

FILE - In this Sept. 22, 2016, file photo, Lou Lamoriello leaves an NHL hockey news conference in Toronto. (Chris Young/The Canadian Press via AP, File)

FILE - New York Islanders president and general manager Lou Lamoriello responds to questions after the second day of the NHL hockey draft, June 29, 2023, in Nashville, Tenn. (AP Photo/George Walker IV, file)

COLUMBUS, Ohio (AP) — Whether it’s stand-up comedy specials or a dramedy series, when Muslim American Mo Amer sets out to create, he writes what he knows.

The comedian, writer and actor of Palestinian descent has received critical acclaim for it, too. The second season of Amer's “Mo” documents Mo Najjar and his family’s tumultuous journey reaching asylum in the United States as Palestinian refugees.

Amer's show is part of an ongoing wave of television from Arab American and Muslim American creators who are telling nuanced, complicated stories about identity without falling into stereotypes that Western media has historically portrayed.

“Whenever you want to make a grounded show that feels very real and authentic to the story and their cultural background, you write to that,” Amer told The Associated Press. “And once you do that, it just feels very natural, and when you accomplish that, other people can see themselves very easily.”

At the start of its second season, viewers find Najjar running a falafel taco stand in Mexico after he was locked in a van transporting stolen olive trees across the U.S.-Mexico border. Najjar was trying to retrieve the olive trees and return them to the farm where he, his mother and brother are attempting to build an olive oil business.

Both seasons of “Mo” were smash hits on Netflix. The first season was awarded a Peabody. His third comedy special on Netflix, “Mo Amer: Wild World,” premiered in October.

Narratively, the second season ends before the Hamas attack in Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, but the series itself doesn't shy away from addressing Israeli-Palestinian relations, the ongoing conflict in Gaza or what it's like for asylum seekers detained in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention centers.

In addition to “Mo,” shows like “Muslim Matchmaker,” hosted by matchmakers Hoda Abrahim and Yasmin Elhady, connect Muslim Americans from around the country with the goal of finding a spouse.

The animated series, “#1 Happy Family USA,” created by Ramy Youssef, who worked with Amer to create “Mo,” and Pam Brady, follows an Egyptian American Muslim family navigating life in New Jersey after the 9/11 terrorists attack in New York.

The key to understanding the ways in which Arab or Muslim Americans have been represented on screen is to be aware of the “historical, political, cultural and social contexts” in which the content was created, said Sahar Mohamed Khamis, a University of Maryland professor who studies Arab and Muslim representation in media.

After the 9/11 attacks, Arabs and Muslims became the villains in many American films and TV shows. The ethnic background of Arabs and the religion of Islam were portrayed as synonymous, too, Khamis said. The villain, Khamis said, is often a man with brown skin with an Arab-sounding name.

A show like “Muslim Matchmaker” flips this narrative on its head, Elhady said, by showing the ethnic diversity of Muslim Americans.

“It’s really important to have shows that show us as everyday Americans," said Elhady, who is Egyptian and Libyan American, "but also as people that live in different places and have kind of sometimes dual realities and a foot in the East and a foot in the West and the reality of really negotiating that context."

Before 9/11, people living in the Middle East were often portrayed to Western audiences as exotic beings, living in tents in the desert and riding camels. Women often had little to no agency in these media depictions and were “confined to the harem” — a secluded location for women in a traditional Muslim home.

This idea, Khamis said, harkens back to the term “orientalism,” which Palestinian American academic, political activist and literary critic Edward Said coined in his 1978 book of the same name.

Khamis said, pointing to countries like Britain and France, the portrayal in media of people from the region was "created and manufactured, not by the people themselves, but through the gaze of an outsider. The outsiders in this case, he said, were the colonial/imperialist powers that were actually controlling these lands for long periods of time.”

Among those who study the ways Arabs have been depicted on Western television, a common critique is that the characters are “bombers, billionaires or belly dancers,” she said.

Sanaz Alesafar, executive director of Storyline Partners and an Iranian American, said she has seen some “wins” with regard to Arab representation in Hollywood, noting the success of “Mo,” “Muslim Matchmaker” and “#1 Happy Family USA.” Storyline Partners helps writers, showrunners, executives and creators check the historical and cultural backgrounds of their characters and narratives to assure they’re represented fairly and that one creator’s ideas don't infringe upon another's.

Alesafar argues there is still a need for diverse stories told about people living in the Middle East and the English-speaking diaspora, written and produced by people from those backgrounds.

“In the popular imagination and popular culture, we’re still siloed in really harmful ways,” she said. “Yes, we’re having these wins and these are incredible, but that decision-making and centers of power still are relegating us to these tropes and these stereotypes.”

Deana Nassar, an Egyptian American who is head of creative talent at film production company Alamiya Filmed Entertainment, said it's important for her children to see themselves reflected on screen “for their own self image.” Nassar said she would like to see a diverse group of people in decision-making roles in Hollywood. Without that, it's “a clear indication that representation is just not going to get us all the way there,” she said.

Representation can impact audiences’ opinions on public policy, too, according to a recent study by the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding. Results showed that the participants who witnessed positive representation of Muslims were less likely to support anti-democratic and anti-Muslim policies compared to those who viewed negative representations.

For Amer, limitations to representation come from the decision-makers who greenlight projects, not from creators. He said the success of shows like his and others are a “start,” but he wants to see more industry recognition for his work and the work of others like him.

“That's the thing, like just keep writing, that's all it's about," he said. "Just keep creating and keep making and thankfully I have a really deep well for that, so I’m very excited about the next things,” he said.

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

FILE - Mohammed Amer attends the Gotham Independent Film Awards at Cipriani Wall Street on Nov. 28, 2022, in New York. (Photo by Evan Agostini/Invision/AP, File)

FILE - Yasmin Elhady, a matchmaker featured on the series, "Muslim Matchmaker," on Hulu, poses in Falls Church, Va, on Aug. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Mariam Zuhaib, File)

FILE - Actor Ramy Youssef attends the, "#1 Happy Family USA," premiere at Metrograph on April 16, 2025, in New York. (Photo by Andy Kropa/Invision/AP, File)

FILE - Hoda Abrahim, founder and CEO of, "Love, Inshallah," a matchmaker featured on the series, "Muslim Matchmaker," on Hulu, appears in her home on Aug. 11, 2025, in Conroe, Texas. (AP Photo/Ashley Landis, File)