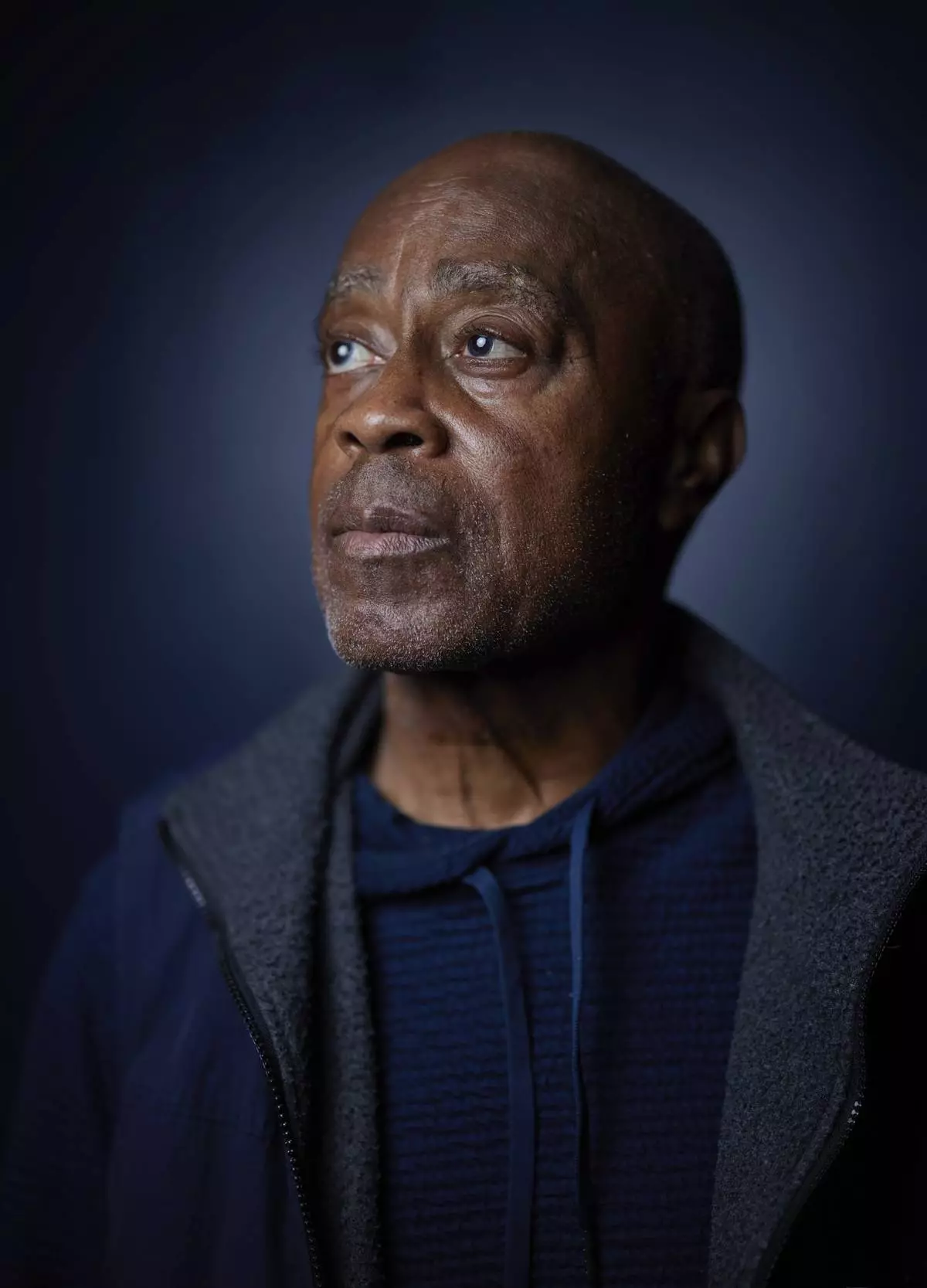

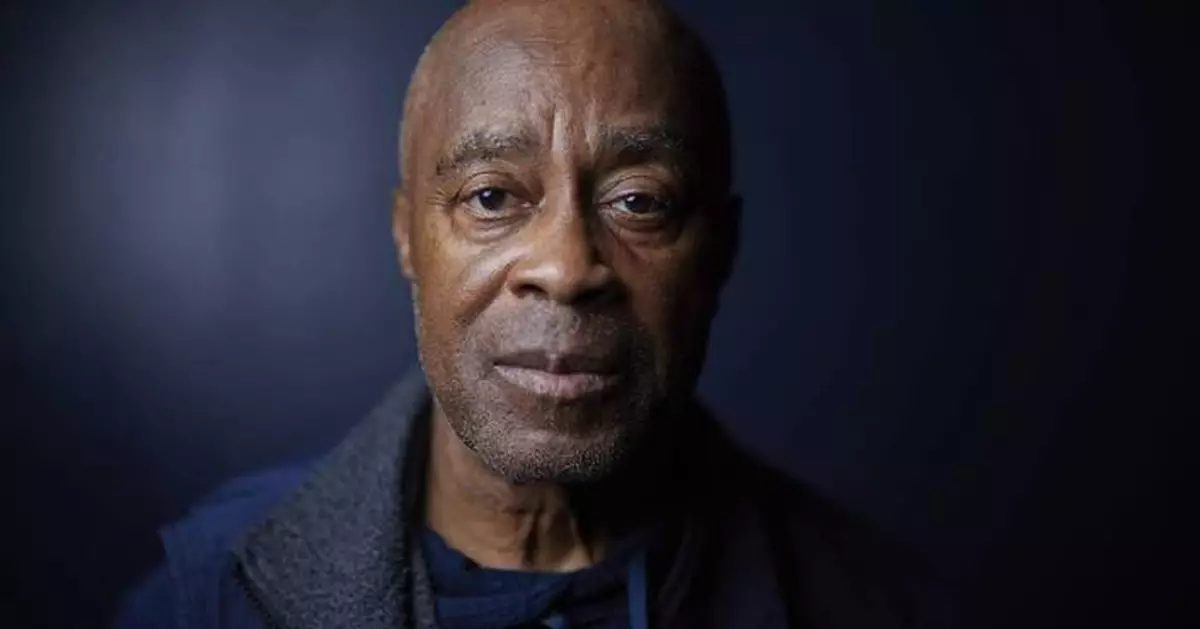

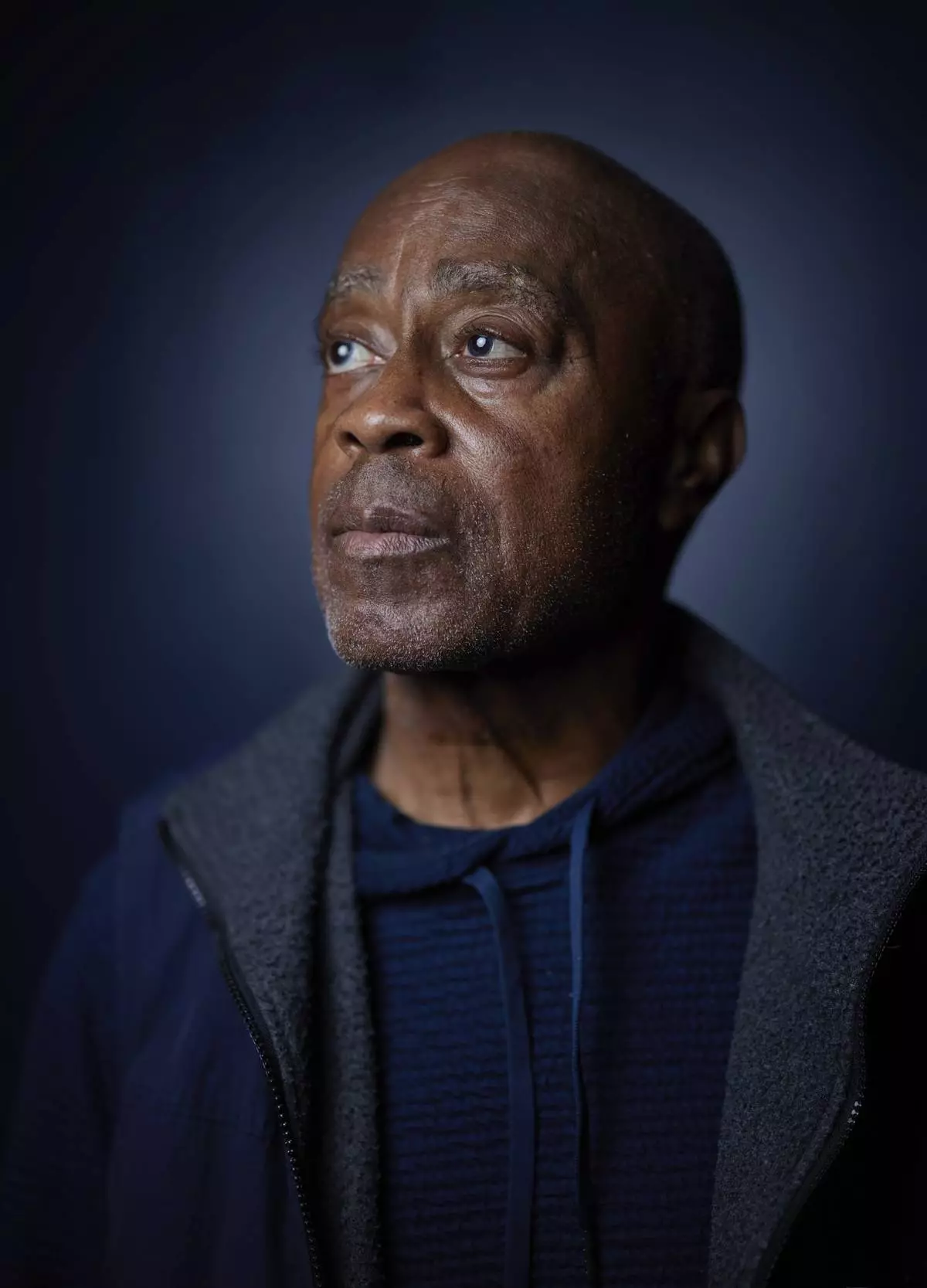

NEW YORK (AP) — Charles Burnett has been living with “Killer of Sheep” for more than half a century.

Burnett, 81, shot “Killer of Sheep” on black-and-white 16mm in the early 1970s for less than $10,000. Originally Burnett’s thesis film at UCLA, it was completed in 1978. In the coming years, “Killer of Sheep” would be hailed as a masterpiece of Black independent cinema and one of the finest film debuts, ever. Though it didn’t receive a widespread theatrical release until 2007, the blues of “Killer of Sheep” have sounded across generations of American movies.

And time has only deepened the gentle soulfulness of Burnett’s film, a portrait of the slaughterhouse worker Stan (Henry G. Sanders) and his young family in Los Angeles’ Watts neighborhood. “Killer of Sheep” was then, and remains, a rare chronicle of working-class Black life, radiant in lyrical poetry — a couple slow dancing to Dinah Washington’s “This Bitter Earth,” boys leaping between rooftops — and hard-worn with daily struggle.

A new 4K restoration — complete with the film’s full original score — is now playing in theaters, an occasion that recently brought Burnett from his home in Los Angeles to New York, where he met The Associated Press shortly after arriving.

Burnett’s career has been marked by revival and rediscovery (he received an honorary Oscar in 2017), but this latest renaissance has been an especially vibrant one. In February, Kino Lorber released Burnett’s “The Annihilation of Fish,” a 1999 film starring James Earl Jones and Lynn Redgrave that had never been commercially distributed. It was widely hailed as a quirky lost gem about a pair of lost souls.

On Friday, Lincoln Center launches “L.A. Rebellion: Then and Now,” a film series about the movement of 1970s UCLA filmmakers, including Burnett, Julie Dash and Billy Woodberry, who remade Black cinema.

The Mississippi-born, Watts-raised Burnett is soft-spoken but has much to say — only some of which has filtered into his seven features (among them 1990’s “To Sleep With Anger”) and numerous short films (some of the best are “When It Rains” and “The Horse”). The New Yorker’s Richard Brody once called the unmade films of Burnett and his L.A. Rebellion contemporaries “modern cinema’s holy spectres.”

But on a recent spring day, Burnett’s mind was more on Stan of “Killer of Sheep.” Burnett sees his protagonist's pain and endurance less as a thing of the past than as a frustratingly eternal plight. If “Killer of Sheep” was made to capture the humanity of a Black family and give his community a dignity that had been denied them, Burnett sees the same need today. The conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

BURNETT: I grew up in a neighborhood (Watts) where everyone was from the South. There was a lot of tradition. It was a different culture, a different group of people living there — people who had experienced a great deal and kept their humanity. And they had a work ethic. It was a nice atmosphere. People looked after you. I grew up with people who were very gentle. There were the Watts riots when you couldn't walk down the street without police harassing you. Police would stop me and do this forensic search and call you all kind of names while doing it. But in the riots, it wasn't that people got braver. They just got tired. When people got together, they always had the perspective of: Let the kids eat first.

BURNETT: In “Killer of Sheep,” kids were learning how to be men or women. The changing point was when Emmett Till and his picture was being shown everywhere in Jet magazine. All of a sudden, it was no longer this fantasy. You were now aware of the cruelty of the world. I remember a kid who had come home abused, who supposedly fell down the stairs. You learned this dual reality to life.

BURNETT: Life going by. A life that should have been totally different. In high school, I had a teacher who would go walking down the aisle pointing at students saying, “You’re not going to be anything, you’re not going to be anything.” He got to me and said, “You’re not going to be anything.” Now, (Florida Gov. Ron) DeSantis wants to destroy Black history. It’s always a battle.

BURNETT: Young kids were capable of so much more. We were all looking for a place where you felt like you belonged. America could have been so much greater. The whole world could have been better.

BURNETT: You do the best you can with what you have. There are so many things you want to say. What you find is that sometimes you work with people that don’t see eye to eye. Even though I didn’t do more, it’s still more than what some people made, by far. I’m very happy about that. On the flip side, a lot of times you hear, “Your films changed my life.” And if you can get that, then you’re doing good. One of the things that I found is that people will take advantage of you and make you make the film that they want to make. You need to be somehow independent where you can tell them, “No, I’m not doing this.” I had to do that a number of times. So you don’t work that often.

BURNETT: One of the reasons I did “Killer of Sheep” the way I did, with kids in the community working in all areas of the production, was to show them that they could do it. I made the film to restore our history, so young people could grow from it and know: I can do this. Even when I was in film school, there was a film production going on in my neighborhood. I was on my bike and I rolled over to see. I asked a guy, “What set is this?” and he acted like I wouldn’t understand. It’s changed a bit but there’s still this attitude. You look at what Trump and these guys are doing with DEI. It’s this constant battle. It can never end. You have to constantly prove yourself. It’s a battle, ongoing, ongoing, ongoing.

This story has been corrected to report that Burnett received his honorary Oscar in 2017, not 2007, and that he's 81, not 82.

Filmmaker Charles Burnett poses for a portrait on Saturday, April 19, 2025, in New York. (Photo by Matt Licari/Invision/AP)

Filmmaker Charles Burnett poses for a portrait on Saturday, April 19, 2025, in New York. (Photo by Matt Licari/Invision/AP)

Filmmaker Charles Burnett poses for a portrait on Saturday, April 19, 2025, in New York. (Photo by Matt Licari/Invision/AP)

ORCHARD PARK, N.Y. (AP) — Buffalo Bills fans arrived early and lingered long after the game ended to bid what could be farewell to their long-time home stadium filled with 53 years of memories — and often piles of snow.

After singing along together to The Killers' “Mr. Brightside” in the closing minutes of a 35-8 victory against the New York Jets, most everyone in the crowd of 70,944 remained in their seats to bask in the glow of fireworks as Louis Armstrong's "What A Wonderful World” played over the stadium speakers.

Several players stopped in the end zone to watch a retrospective video, with the Buffalo-based Goo Goo Dolls’ “Iris” as the soundtrack while fans recorded selfie videos of the celebratory scene. Offensive lineman Alec Anderson even jumped into the crowd to pose for pictures before leaving the field.

With the Bills (12-5), the AFC's 6th seed, opening the playoffs at Jacksonville in the wild-card round next week, there's but a slim chance they'll play at their old home again. Next season, Buffalo is set to move into its new $1.2 billion facility being built across the street.

The farewell game evoked “a lifetime of memories,” said Therese Forton-Barnes, selected the team’s Fan of the Year, before the Bills kicked of their regular-season finale. “In our culture that we know and love, we can bond together from that experience. Our love for this team, our love for this city, have branched from those roots.”

Forton-Barnes, a past president of the Greater Buffalo Sports Hall of Fame, attended Bills games as a child at the old War Memorial Stadium in downtown Buffalo, colloquially known as “The Rockpile.” She has been a season ticket holder since Jim Kelly joined the Bills in 1986 at what was then Rich Stadium, later renamed for the team’s founding owner Ralph Wilson, and then corporate sponsors New Era and Highmark.

“I’ve been to over 350 games,” she said. “Today we’re here to cherish and celebrate the past, present and future. We have so many memories that you can’t erase at Rich Stadium, The Ralph, and now Highmark. Forever we will hold these memories when we move across the street.”

There was a celebratory mood to the day, with fans arriving early. Cars lined Abbott Road some 90 minutes before the stadium lots opened for a game the Bills rested most of their starters, with a brisk wind blowing in off of nearby Lake Erie and with temperatures dipping into the low 20s.

And most were in their seats when Bills owner Terry Pegula thanked fans and stadium workers in a pregame address.

With Buffalo leading 21-0 at halftime, many fans stayed in their seats as Kelly and fellow Pro Football Hall of Famer Andre Reed addressed them from the field, and the team played a video message from 100-year-old Hall of Fame coach Marv Levy.

“The fans have been unbelievable,” said Jack Hofstetter, a ticket-taker since the stadium opened in 1973 who was presented with Super Bowl tickets before Sunday’s game by Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield. “I was a kid making 8 bucks a game back in those days. I got to see all the sports, ushering in the stadium and taking tickets later on. All the memories, it’s been fantastic.”

Bud Light commemorated the stadium finale and Bills fan culture with the release of a special-edition beer brewed with melted snow shoveled out of the stadium earlier this season.

In what has become a winter tradition at the stadium, fans were hired to clear the stands after a lake-effect storm dropped more than a foot of snow on the region this week.

The few remaining shovelers were still present clearing the pathways and end zone stands of snow some five hours before kickoff. The new stadium won’t require as many shovelers, with the field heated and with more than two-thirds of the 60,000-plus seats covered by a curved roof overhang.

Fears of fans rushing the field were abated with large contingent of security personnel and backed by New York State troopers began lining the field during the final 2-minute warning.

Fans stayed in the stands, singing along to the music, with many lingering to take one last glimpse inside the stadium where the scoreboard broadcast one last message:

“Thank You, Bills Mafia.”

AP Sports Writer John Wawrow contributed.

AP NFL: https://apnews.com/hub/nfl

Fans watch a ceremony after the Buffalo Bills beat the New York Jets in the Bills' final regular-season NFL football home game in Highmark Stadium Sunday, Jan. 4, 2026, in Orchard Park, N.Y. (AP Photo/Adrian Kraus)

Buffalo Bills cornerback Tre'Davious White (27) remains on the field to watch a tribute video after the Bills beat the New York Jets in the Bills' final regular-season NFL football home game in Highmark Stadium Sunday, Jan. 4, 2026, in Orchard Park, N.Y.(AP Photo/Adrian Kraus)

Fans watch a ceremony after the Buffalo Bills beat the New York Jets in the Bills' final regular-season NFL football home game in Highmark Stadium Sunday, Jan. 4, 2026, in Orchard Park, N.Y. (AP Photo/Adrian Kraus)

Fans celebrate after the Buffalo Bills scored a touchdown during the first half of an NFL football game against the New York Jets, Sunday, Jan. 4, 2026, in Orchard Park, N.Y. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Fans celebrate and throw snow in the stands after an NFL football game between the Buffalo Bills and the New York Jets, Sunday, Jan. 4, 2026, in Orchard Park, N.Y. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Aga Deters, right, and her husband Fred Deters, walk near Highmark Stadium before an NFL football game between the Buffalo Bills and the New York Jets, Sunday, Jan. 4, 2026, in Orchard Park, N.Y. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Michael Wygant shoves snow from a tunnel before an NFL football game between the Buffalo Bills and the New York Jets at Highmark Stadium, Sunday, Jan. 4, 2026, in Orchard Park, N.Y. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Buffalo Bills offensive tackle Alec Anderson (70) spikes the ball after running back Ty Johnson scored a touchdown against the New York Jets in the first half of an NFL football game Sunday, Jan. 4, 2026, in Orchard Park, N.Y. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

FILE - The existing Highmark Stadium, foreground, frames the construction on the new Highmark Stadium, upper right, which is scheduled to open with the 2026 season, shown before an NFL football game between the Buffalo Bills and the New England Patriots, Oct. 5, 2025, in Orchard Park, N.Y. (AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar, File)

Salt crew member Jim Earl sprinkles salt in the upper deck before an NFL football game between the Buffalo Bills and the New York Jets at Highmark Stadium, Sunday, Jan. 4, 2026, in Orchard Park, N.Y. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)