PENN YAN, N.Y. (AP) — A decade ago, Scott Osborn would have eagerly told prospective vineyard owners looking to join the wine industry to “jump into it.”

Now, his message is different.

“You’re crazy,” said Osborn, who owns Fox Run Vineyards, a sprawling 50-acre (20-hectare) farm on Seneca Lake, the largest of New York’s Finger Lakes.

It’s becoming riskier to grow grapes in the state’s prominent winemaking region. Harvests like Osborn’s are increasingly endangered by unpredictable weather from climate change. Attitudes on wine are shifting. Political tensions, such as tariffs amid President Donald Trump’s trade wars and the administration’s rollback of environmental policies, are also looming problems.

Despite the challenges, however, many winegrowers are embracing sustainable practices, wanting to be part of the solution to global warming while hoping they can adapt to changing times.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story is a collaboration between Rochester Institute of Technology and The Associated Press.

The Finger Lakes, which span a large area of western New York, have water that can sparkle and give off a sapphire hue on sunny days. More than 130 wineries dot the shorelines and offer some of America’s most famous white wines.

At Fox Run, visitors step inside to sip wines and bring a bottle — or two — home. Many are longtime customers, like Michele Magda and her husband, who have frequently made the trip from Pennsylvania.

“This is like a little escape, a little getaway,” she said.

Traditionally, the plants’ buds break out in spring, emerging with colorful grapes that range from the cabernet franc’s deep blues to the soft greens of the region’s most popular grape, riesling. However, a warming world is making that happen earlier, adding to uncertainty and potential risks for farmers. If a frost comes after the buds have broken, growers can lose much of the harvest.

Year-round rain and warmer night temperatures differentiate the Finger Lakes from its West Coast competitors, said Paul Brock, a viticulture and wine technology professor at Finger Lakes Community College. Learning to adapt to those fluctuations has given local winemakers a competitive advantage, he said.

Globally, vineyards are grappling with the impacts of increasingly unpredictable weather. In France, record rainfall and harsh weather have spelled trouble for winegrowers trying their best to adapt. Along the West Coast, destructive wildfires are worsening wine quality.

Many winegrowers say they are working to make their operations more sustainable, wanting to help solve climate change caused by the burning of fuels like gasoline, coal and natural gas.

Farms can become certified under initiatives such as the New York Sustainable Winegrowing program. Fox Run and more than 50 others are certified, which requires that growers improve practices like bettering soil health and protecting water quality of nearby lakes.

Beyond the rustic metal gate featuring the titular foxes, some of Osborn’s sustainability initiatives come into view.

Hundreds of solar panels powering 90% of the farm’s electricity are the most obvious feature. Other initiatives are more subtle, like underground webs of fungi used to insulate crops from drought and disease.

“We all have to do something,” Osborn said.

For Suzanne Hunt and her family’s 7th-generation vineyard, doing something about climate change means devoting much of their efforts to sustainability.

Hunt Country Vineyards, along Keuka Lake, took on initiatives like using underground geothermal pipelines for heating and cooling, along with composting. Despite the forward-looking actions, climate change is one of the factors forcing the family to make tough decisions about their future.

Devastating frosts in recent years have caused “catastrophic” crop loss. They’ve also had to reconcile with changing consumer attitudes, as U.S. consumption of wine fell over the past few years, according to wine industry advocacy group Wine Institute.

By this year’s end, the vineyard will stop producing wine and instead will hold community workshops and sell certain grape varieties.

“The farm and the vineyard, you know, it’s part of me,” Hunt said, adding that she wanted to be able to spend all of her time helping other farms and businesses implement sustainable practices. “I’ll let the people whose dream and life is to make wine do that part, and I’ll happily support them.”

Vinny Aliperti, owner of Billsboro Winery along Seneca Lake, is working to improve the wine industry’s environmental footprint. In the past year, he’s helped establish communal wine bottle dumpsters that divert the glass from entering landfills and reuse it for construction materials.

But Aliperti said he’d like to see more nearby wineries and vineyards in sustainability efforts. The wine industry’s longevity depends on it, especially under a presidential administration that doesn’t seem to have sustainability at top of mind, he said.

“I think we’re all a bit scared, frankly, a bit, I mean, depressed,” he said. “I don’t see very good things coming out of the next four years in terms of the environment.”

Osborn is bracing for sweeping cuts to federal environmental policies that previously made it easier to fund sustainability initiatives. Tax credits for Osborn’s solar panels made up about half of over $400,000 in upfront costs, in addition to some state and federal grants. Osborn wants to increase his solar production, but he said he won’t have enough money without those programs.

Fox Run could also lose thousands of dollars from retaliatory tariffs and boycotts of American wine from his Canadian customers. In March, Canada introduced 25% tariffs on $30 billion worth of U.S. goods — including wine.

Osborn fears he can’t compete with larger wine-growing states like California, which may flood the American market to make up for lost customers abroad. Smaller vineyards in the Finger Lakes might not survive these economic pressures, he said.

Back at Fox Run's barrel room, Aric Bryant, a decade-long patron, says all the challenges make him even more supportive of New York wines.

“I have this, like, fierce loyalty,” he said. "I go to restaurants around here and if they don’t have Finger Lakes wines on their menu, I’m like, ‘What are you even doing serving wine?’”

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

This story was first published on April 23, 2025. It was updated on April 28, 2025, to add context about the decision to close Hunt Country Vineyards by the end of the year.

Solar panels operate at Fox Run Vineyards and Seneca Lake, Friday, March 21, 2025, in Penn Yan, N.Y. (Natasha Kaiser via AP)

Roark Castner works at Anthony Road Winery, Saturday, March 22, 2025, in Penn Yan, N.Y. (Natasha Kaiser via AP)

A sign that reads, "What happens at the winery stays at the winery," sits on a shelf in the head winemaker's office at Fox Run Vineyards, Friday, March 21, 2025, in Penn Yan, N.Y. (Natasha Kaiser via AP)

Rose and Paul Wells taste wine at Fox Run Vineyards, Saturday, March 22, 2025, in Penn Yan, N.Y. (Natasha Kaiser via AP)

Scott Osborn, owner of Fox Run Vineyards, chats with customers Friday, March 21, 2025, in Penn Yan, N.Y. (Natasha Kaiser via AP)

Solar panels operate at Fox Run Vineyards and Seneca Lake, Friday, March 21, 2025, in Penn Yan, N.Y. (Natasha Kaiser via AP)

A tractor moves along rows between dormant grapevines at Fox Run Vineyards, Friday, March 21, 2025, in Penn Yan, N.Y. (Natasha Kaiser via AP)

Scott Osborn, owner of Fox Run Vineyards, walks past wine barrels, Friday, March 21, 2025, in Penn Yan, N.Y. (Natasha Kaiser via AP)

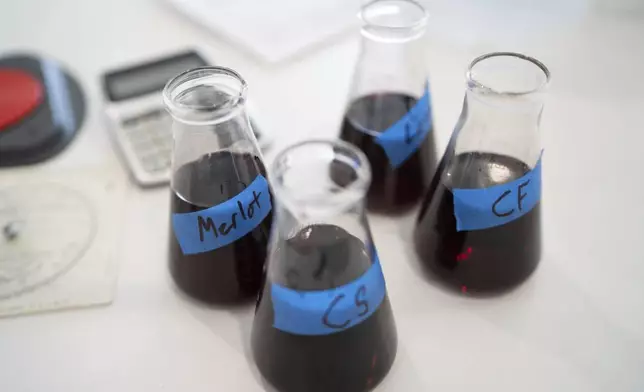

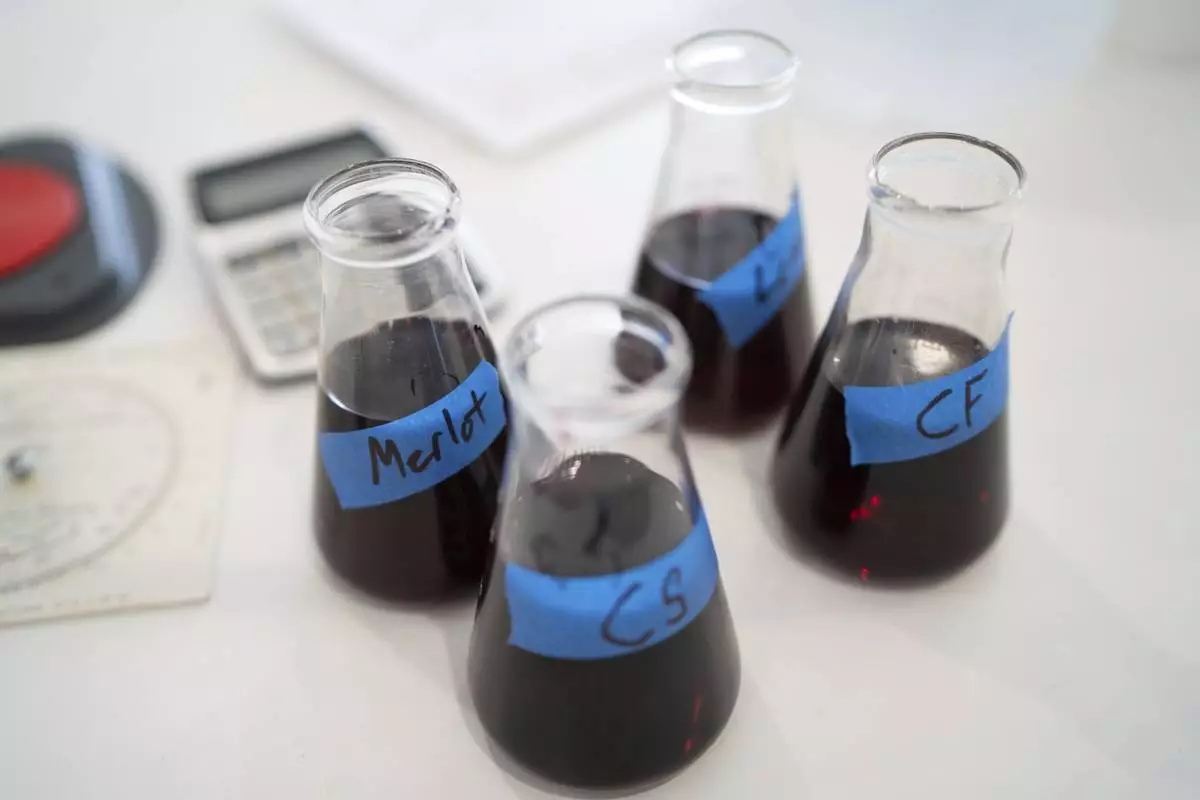

Samples of red wine sit on a table in the head winemaker's office at Fox Run Vineyards, Friday, March 21, 2025, in Penn Yan, N.Y. (Natasha Kaiser via AP)

Head winemaker Craig Hosbach walks past rows of wine tanks at Fox Run Vineyards on Friday, March 21, 2025, in Penn Yan, N.Y. (Natasha Kaiser via AP)

Scott Osborn, owner of Fox Run Vineyards, enters a wine production building Friday, March 21, 2025, in Penn Yan, N.Y. (Natasha Kaiser via AP)

Scott Osborn, owner of Fox Run Vineyards, walks through the vineyards past solar panels Friday, March 21, 2025, in Penn Yan, N.Y. (Natasha Kaiser via AP)

Scott Osborn, owner of Fox Run Vineyards, stands for a photo, Friday, March 21, 2025, in Penn Yan, N.Y. (Natasha Kaiser via AP)

Scott Osborn, owner of Fox Run Vineyards, walks past dormant grapevines, Friday, March 21, 2025, in Penn Yan, N.Y. (Natasha Kaiser via AP)