SANTIAGO, Chile (AP) — As a child, Susana Moreira didn’t have the same energy as her siblings. Over time, her legs stopped walking and she lost the ability to bathe and take care of herself. Over the last two decades, the 41-year-old Chilean has spent her days bedridden, suffering from degenerative muscular dystrophy. When she finally loses her ability to speak or her lungs fail, she wants to be able to opt for euthanasia — which is currently prohibited in Chile.

Moreira has become the public face of Chile’s decade-long debate over euthanasia and assisted dying, a bill that the left-wing government of President Gabriel Boric has pledged to address in his last year in power, a critical period for its approval ahead of November’s presidential election.

“This disease will progress, and I will reach a point where I won’t be able to communicate,” Moreira told The Associated Press from the house where she lives with her husband in southern Santiago. “When the time comes, I need the euthanasia bill to be a law.”

In April 2021, Chile’s Chamber of Deputies approved a bill to allow euthanasia and assisted suicide for those over 18 who suffer from a terminal or “serious and incurable” illness. But it has since been stalled in the Senate.

The initiative seeks to regulate euthanasia, in which a doctor administers a drug that causes death, and assisted suicide, in which a doctor provides a lethal substance that the patients take themselves.

If the bill passes, Chile will join a select group of countries that allow both euthanasia and assisted suicide, including the Netherlands, Belgium, Canada, Spain and Australia.

It would also make Chile the third Latin American country to rule on the matter, following Colombia’s established regulations and Ecuador’s recent decriminalization, which remains unimplemented due to a lack of regulation.

When she was 8 years old, Moreira was diagnosed with shoulder-girdle muscular dystrophy, a progressive genetic disease that affects all her muscles and causes difficulty breathing, swallowing and extreme weakness.

Confined to bed, she spends her days playing video games, reading and watching Harry Potter movies. Outings are rare and require preparation, as the intense pain only allows her three or four hours in the wheelchair. As the disease progressed, she said she felt the “urgency” to speak out in order to advance the discussion in Congress.

“I don’t want to live plugged into machines, I don’t want a tracheostomy, I don’t want a feeding tube, I don’t want a ventilator to breathe. I want to live as long as my body allows me,” she said.

In a letter to President Boric last year, Moreira revealed her condition, detailed her daily struggles and asked him to authorize her euthanasia.

Boric made Moreira’s letter public to Congress in June and announced that passing the euthanasia bill would be a priority in his final year in office. “Passing this law is an act of empathy, responsibility and respect,” he said.

But hope soon gave way to uncertainty.

Almost a year after that announcement, multiple political upheavals have relegated Boric’s promised social agenda to the background.

Chile, a country of roughly 19 million inhabitants at the southern tip of the southern hemisphere, began to debate euthanasia more than ten years ago. Despite a predominantly Catholic population and the strong influence of the Church at the time, Representative Vlado Mirosevic, from Chile's Liberal Party, first presented a bill for euthanasia and assisted dying in 2014.

The proposal was met with skepticism and strong resistance. Over the years, the bill underwent numerous modifications with little significant progress until 2021. “Chile was then one of the most conservative countries in Latin America,” Mirosevic told the AP.

More recently, however, public opinion has shifted, showing greater openness to debating thorny issues. “There was a change in the mood," Mirosevic said, citing the rising support for the euthanasia bill among Chileans.

Indeed, recent surveys show strong public support for euthanasia and assisted dying in Chile.

According to a 2024 survey by Chilean public opinion pollster Cadem, 75% of those interviewed said they supported euthanasia, while a study by the Center for Public Studies from October found that 89% of Chileans believe euthanasia should “always be allowed” or “allowed in special cases,” compared to 11% who believed the procedure "should never be allowed.”

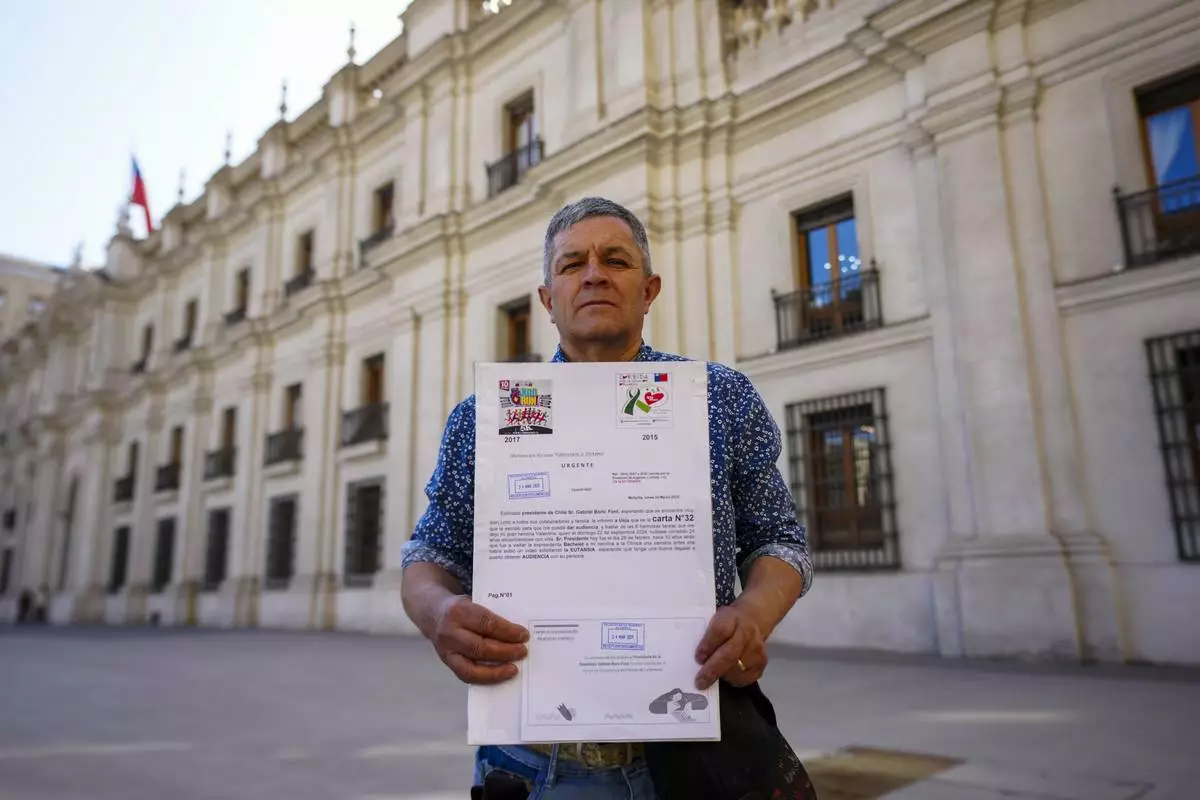

Boric’s commitment to the euthanasia bill has been welcomed by patients and families of those lost to terminal illnesses, including Fredy Maureira, a decade-long advocate for the right of choosing when to die.

His 14-year-old daughter Valentina went viral in 2015, after posting a video appealing to then-President Michelle Bachelet for euthanasia. Her request was denied, and she died less than two months later from complications of cystic fibrosis.

The commotion generated both inside and outside Chile by her story allowed the debate on assisted death to penetrate also into the social sphere.

“I addressed Congress several times, asking lawmakers to put themselves in the shoes of someone whose child or sibling is pleading to die, and there’s no law to allow it," said Maureira.

Despite growing public support, euthanasia and assisted death remains a contentious issue in Chile, including among health professionals.

“Only when all palliative care coverage is available and accessible, will it be time to sit down and discuss the euthanasia law,” Irene Muñoz Pino, a nurse, academic and advisor to the Chilean Scientific Society of Palliative Nursing, said. She was referring to a recent law, enacted in 2022, that ensures palliative care and protects the rights of terminally ill individuals.

Others argue that the absence of a legal medical option for assisted dying could lead patients to seek other riskier, unsupervised alternatives.

“Unfortunately, I keep hearing about suicides that could have been instances of medically assisted death or euthanasia,” said Colombian psychologist Monica Giraldo.

With only a few months remaining, Chile’s leftist government faces a narrow window to pass the euthanasia bill before the November presidential elections dominate the political agenda.

“A sick person isn’t certain of anything; the only certainty they have is that they will suffer,” Moreira said. “Knowing that I have the opportunity to choose, gives me peace of mind."

Follow AP’s coverage of Latin America and the Caribbean at https://apnews.com/hub/latin-america

Fredy Maureira, the father of Valentina, who suffered from cystic fibrosis and died at the age of 14, holds a copy of a letter he left at the presidential palace requesting a meeting with President Gabriel Boric, in Santiago, Chile, Monday, March 24, 2025. (AP Photo/Esteban Felix)

Susana Moreira, 41, a degenerative muscular dystrophy patient, gives an interview in her bedroom in Santiago, Chile, Monday, April 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Esteban Felix)

Susana Moreira, 41, a degenerative muscular dystrophy patient, looks at her husband in her bedroom in Santiago, Chile, Thursday, April 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Esteban Felix)