TEL AVIV, Israel (AP) — Israel has blocked aid from entering Gaza for two months and says it won’t allow food, fuel, water or medicine into the besieged territory until it puts in place a system giving it control over the distribution.

But officials from the U.N. and aid groups say proposals Israel has floated to use its military to distribute vital supplies are untenable. These officials say they would allow military and political objectives to impede humanitarian goals, put restrictions on who is eligible to give and receive aid, and could force large numbers of Palestinians to move — which would violate international law.

Israel has not detailed any of its proposals publicly or put them down in writing. But aid groups have been documenting their conversations with Israeli officials, and The Associated Press obtained more than 40 pages of notes summarizing Israel’s proposals and aid groups’ concerns about them.

Aid groups say Israel shouldn’t have any direct role in distributing aid once it arrives in Gaza, and most are saying they will refuse to be part of any such system.

“Israel has the responsibility to facilitate our work, not weaponize it,” said Jens Laerke, a spokesperson for the U.N. agency that oversees the coordination of aid Gaza.

“The humanitarian community is ready to deliver, and either our work is enabled ... or Israel will have the responsibility to find another way to meet the needs of 2.1 million people and bear the moral and legal consequences if they fail to do so,” he said.

None of the ideas Israel has proposed are set in stone, aid workers say, but the conversations have come to a standstill as groups push back.

The Israeli military agency in charge of coordinating aid to Gaza, known as COGAT, did not respond to a request for comment and referred AP to the prime minister’s office. The prime minister's office did not respond either.

Since the beginning of March, Israel has cut off Gaza from all imports, leading to what is believed to be the most severe shortage of food, medicine and other supplies in nearly 19 months of war with Hamas. Israel says the goal of its blockade is to pressure Hamas to free the remaining 59 hostages taken during its October 2023 attack on Israel that launched the war.

Israel says it must take control of aid distribution, arguing without providing evidence that Hamas and other militants siphon off supplies. Aid workers deny there is a significant diversion of aid to militants, saying the U.N. strictly monitors distribution.

One of Israel's core proposals is a more centralized system — made up of five food distribution hubs — that would give it greater oversight, aid groups say.

Israel has proposed having all aid sent through a single crossing in southern Gaza and using the military or private security contractors to deliver it to these hubs, according to the documents shared with AP and aid workers familiar with the discussions. The distribution hubs would all be south of the Netzarim Corridor that isolates northern Gaza from the rest of the territory, the documents say.

One of the aid groups' greatest fears is that requiring Palestinians to retrieve aid from a small number of sites — instead of making it available closer to where they live — would force families to move to get assistance. International humanitarian law forbids the forcible transfer of people.

Aid officials also worry that Palestinians could end up permanently displaced, living in “de facto internment conditions,” according to a document signed by 20 aid groups operating in Gaza.

The hubs also raise safety fears. With so few of them, huge crowds of desperate Palestinians will need to gather in locations that are presumably close to Israeli troops.

“I am very scared about that,” said Claire Nicolet, emergency coordinator for Doctors Without Borders.

There have been several occasions during the war when Israeli forces opened fire after feeling threatened as hungry Palestinians crowded around aid trucks. Israel has said that during those incidents, in which dozens died, many were trampled to death.

Given Gaza's population of more than 2 million people, global standards for humanitarian aid would typically suggest setting up about 100 distribution sites — or 20 times as many as Israel is currently proposing — aid groups said.

Aside from the impractical nature of Israel's proposals for distributing food, aid groups say Israel has yet to address how its new system would account for other needs, including health care and the repair of basic infrastructure, including water delivery.

“Humanitarian aid is more complex than food rations in a box that you pick up once a month,” said Gavin Kelleher, who worked in Gaza for the Norwegian Refugee Council. Aid boxes can weigh more than 100 pounds, and transportation within Gaza is limited, in part because of shortages of fuel.

Experts say Israel is concerned that if Hamas seizes aid, it will then make the population dependent on the armed group in order to access critical food supplies. It could use income from selling the aid to recruit more fighters, said Kobi Michael, a senior researcher at two Israeli think tanks, the Institute for National Security Studies and the Misgav Institute.

As aid groups push back against the idea of Israel playing a direct distribution role within Gaza, Israel has responded by exploring the possibility of outsourcing certain roles to private security contractors.

The aid groups say they are opposed to any armed or uniformed personnel that could potentially intimidate Palestinians or put them at risk.

In the notes seen by AP, aid groups said a U.S.-based security firm, Safe Reach Solutions, had reached out seeking partners to test an aid distribution system around the Netzarim military corridor, just south of Gaza City, the territory’s largest.

Aid groups urged each other not to participate in the pilot program, saying it could set a damaging precedent that could be repeated in other countries facing crises.

Safe Reach Solutions did not respond to requests for a comment.

Whether Israel distributes the aid or employs private contractors to it, aid groups say that would infringe on humanitarian principles, including impartiality and independence.

A spokesperson for the EU Commission said private companies aren’t considered eligible humanitarian aid partners for its grants. The EU opposes any changes that would lead to Israel seizing full control of aid in Gaza, the spokesperson said.

The U.S. State Department declined to comment on ongoing negotiations.

Another concern is an Israeli proposal that would allow authorities to determine if Palestinians were eligible for assistance based on “opaque procedures,” according to aid groups' notes.

Aid groups, meanwhile, have been told by Israel that they will need to re-register with the government and provide personal information about their staffers. They say Israel has told them that, going forward, it could bar organizations for various reasons, including criticism of Israel, or any activities it says promote the “delegitimization” of Israel.

Arwa Damon, founder of the International Network for Aid, Relief and Assistance, says Israel has increasingly barred aid workers from Gaza who had previously been allowed in. In February, Damon was denied access to Gaza, despite having entered four times previously since the war began. Israel gave no reason for barring her, she said.

Aid groups are trying to stay united on a range of issues, including not allowing Israel to vet staff or people receiving aid. But they say they’re being backed into a corner.

“For us to work directly with the military in the delivery of aid is terrifying,” said Bushra Khalidi, Oxfam’s policy lead for Israel and the occupied Palestinian territory. “That should worry every single Palestinian in Gaza, but also every humanitarian worker.”

Associated Press writer Sarah El Deeb in Beirut contributed to this report.

Palestinians struggle in a crowd as they try to receive donated food at a distribution center in Nuseirat, central Gaza Strip, Wednesday, April 30, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

Mira Abu Shaar, 5, right, and her older sister, Raghad, 15, hold pots next to their family tent, as they wait for food to be prepared, in Muwasi, on the outskirts of Khan Younis in the southern Gaza Strip, Thursday, April 24, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

Palestinian children wait to receive donated food at a distribution center in Muwasi, on the outskirts of Khan Younis in the southern Gaza Strip, Thursday, April 24, 2025. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

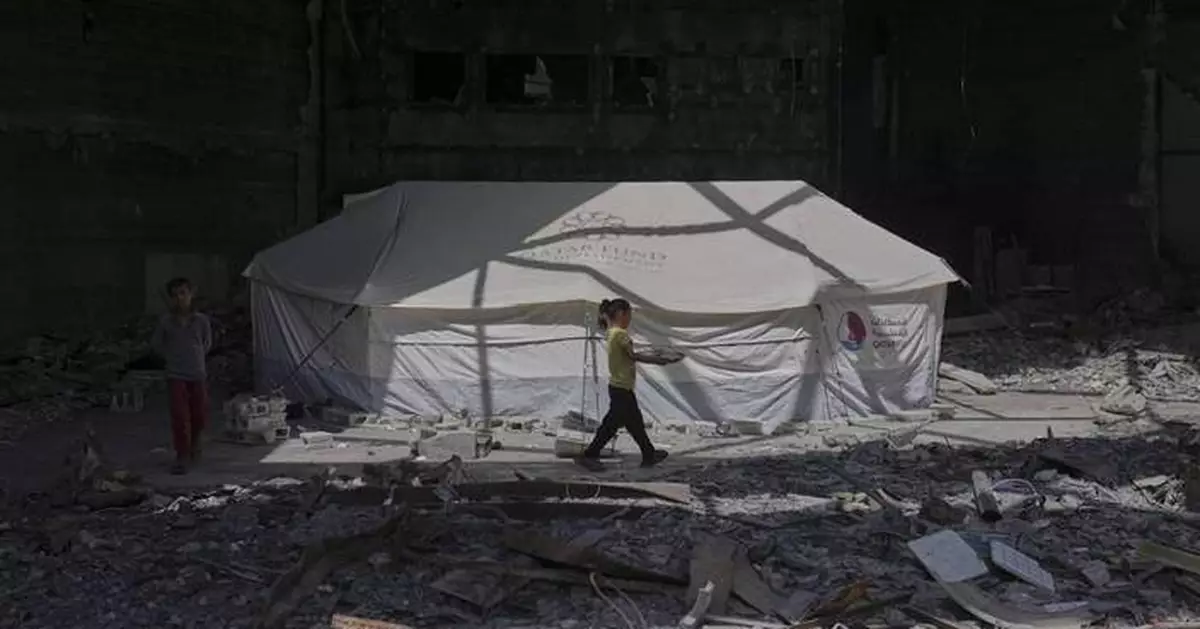

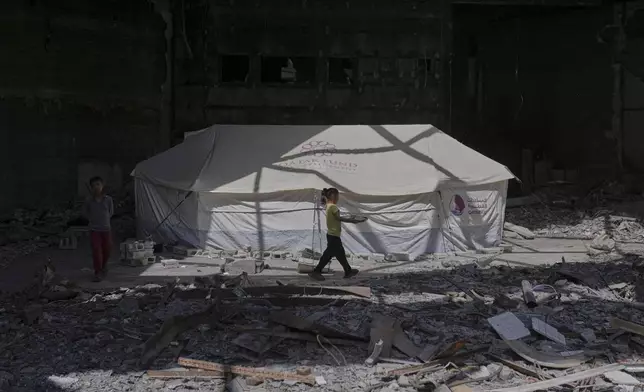

A child carries a tray of food past a tent sheltering displaced Palestinians inside the destroyed Rashad Al-Shawa Cultural Center in Gaza City, Monday, April 21, 2025. (AP Photo/Jehad Alshrafi)