NEW YORK (AP) — U.S. stocks ticked higher Wednesday after the Federal Reserve left its main interest alone, as was widely expected, but also warned about rising risks for the U.S. economy.

The S&P 500 gained 0.4%, coming off a two-day losing streak that had snapped its nine-day winning run. The Dow Jones Industrial Average added 284 points, or 0.7%, and the Nasdaq composite rose 0.3%.

Click to Gallery

Trader Edward Curran works on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, Wednesday, May 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

Trader Dylan Halvorsan works on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, Wednesday, May 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

Specialist Gregg Maloney, left, works on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, Wednesday, May 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

Specialist Anthony Matesic works at his post on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, Wednesday, May 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

Trader Edward McCarthy on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, Tuesday, May 6, 2025. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

A board above the floor of the New York Stock Exchange displays the closing number for the Dow Jones industrial average, Tuesday, May 6, 2025. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

A dealer watches computer monitors near the screen showing the foreign exchange rates at a dealing room of Hana Bank in Seoul, South Korea, Wednesday, May 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

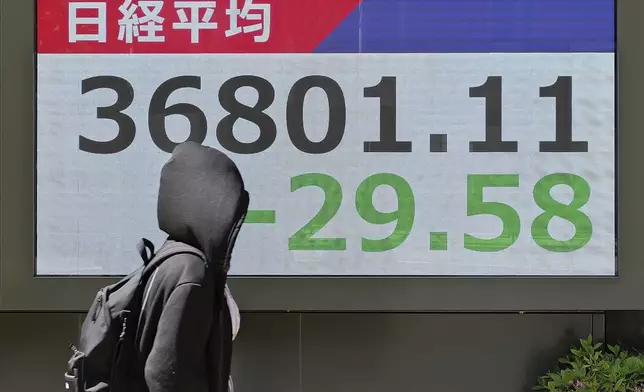

A person walks in front of an electronic stock board showing Japan's Nikkei index at a securities firm Wednesday, May 7, 2025, in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

People pass by an electronic stock board showing Japan's Nikkei index at a securities firm Wednesday, May 7, 2025, in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

A dealer watches computer monitors at a dealing room of Hana Bank in Seoul, South Korea, Wednesday, May 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

A person walks in front of an electronic stock board showing Japan's Nikkei index at a securities firm Wednesday, May 7, 2025, in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Indexes swiveled repeatedly through the day, and the Dow briefly climbed as many as 400 points on hopes that the United States and China may be making the first moves toward a trade deal that could protect the global economy. The world’s two largest economies have been placing ever-increasing tariffs on products coming from each other in an escalating trade war, and the fear is that they could cause a recession unless they allow trade to move more freely.

The announcement for high-level talks between U.S. and Chinese officials this weekend in Switzerland helped raise optimism, but some of that washed away after President Donald Trump said he would not reduce his 145% tariffs on Chinese goods as a condition for negotiations. China has made the de-escalation of the tariffs a requirement for trade negotiations, which the meetings are supposed to help establish.

Such on-and-off uncertainty surrounding tariffs has helped create sharp swings within the U.S. economy, including a rush of imports in the hopes of beating tariffs. Underneath those swings, as well as surveys showing U.S. households are growing much more pessimistic about the future, the Fed said it continues to see the economy running “at a solid pace” at the moment.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell said that gives the central bank time to wait before making any potential moves on interest rates, even if Trump has been lobbying for quicker cuts to juice the economy.

“There’s so much that we don’t know,” Powell said. So like the rest of Wall Street and the world, the Fed is waiting to see what will actually end up happening in Trump’s trade war and whether his tariffs, which were much stiffer than expected, will hit as proposed.

That’s particularly the case after the trade war seems to be entering “a new phase,” Powell said, where the United States is conducting more talks on trade with other countries.

To be sure, the Fed also said it appreciates that risks to the economy are rising because of tariffs, which could both weaken the job market and push inflation higher.

“If the large increases in tariffs that have been announced are sustained, they are likely to generate a rise in inflation, a slowdown in economic growth and an increase in unemployment,” Powell said.

That could ultimately put the Fed in a worst-case scenario called “stagflation,” where the economy is stagnating while inflation remains high. Such a combination is hated because the Fed has no good tools to fix it. If the Fed were to try to cut interest rates to bolster the economy and job market, for example, it could raise inflation further. Raising rates would have the opposite effect.

In the meantime, big U.S. companies continue to produce fatter profits for the start of 2025 than analysts expected.

The Walt Disney Co. jumped 10.8% after easily beating analysts’ profit targets, raising its profit forecast and adding more than a million streaming subscribers.

Companies, though, are also continuing to warn about how uncertainty in the economy is making it more difficult for them to forecast their own finances.

Chipmaker Marvell Technology slumped 8% after it postponed its investor day from June to an undetermined date because of uncertainty over the economy.

All told, the S&P 500 rose 24.37 points to 5,631.28. The Dow Jones Industrial Average added 284.97 points to 41,113.97, and the Nasdaq composite gained 48.50 to 17,738.16.

In the bond market, Treasury yields fell following the Fed’s announcement. The yield on the 10-year Treasury eased to 4.27% from 4.30% late Tuesday.

Markets in Europe mostly lost ground, while markets in Asia rose. Indexes rose 0.1% in Hong Kong and 0.8% in Shanghai after Beijing rolled out interest rate cuts and other moves to help support the Chinese economy and markets as higher tariffs ordered by Trump hit the country’s exports.

AP business writers Elaine Kurtenbach and Matt Ott contributed to this report.

Trader Edward Curran works on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, Wednesday, May 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

Trader Dylan Halvorsan works on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, Wednesday, May 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

Specialist Gregg Maloney, left, works on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, Wednesday, May 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

Specialist Anthony Matesic works at his post on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, Wednesday, May 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

Trader Edward McCarthy on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, Tuesday, May 6, 2025. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

A board above the floor of the New York Stock Exchange displays the closing number for the Dow Jones industrial average, Tuesday, May 6, 2025. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

A dealer watches computer monitors near the screen showing the foreign exchange rates at a dealing room of Hana Bank in Seoul, South Korea, Wednesday, May 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

A person walks in front of an electronic stock board showing Japan's Nikkei index at a securities firm Wednesday, May 7, 2025, in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

People pass by an electronic stock board showing Japan's Nikkei index at a securities firm Wednesday, May 7, 2025, in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

A dealer watches computer monitors at a dealing room of Hana Bank in Seoul, South Korea, Wednesday, May 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

A person walks in front of an electronic stock board showing Japan's Nikkei index at a securities firm Wednesday, May 7, 2025, in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

NEW YORK (AP) — Reviving a campaign pledge, President Donald Trump wants a one-year, 10% cap on credit card interest rates, a move that could save Americans tens of billions of dollars but drew immediate opposition from an industry that has been in his corner.

Trump was not clear in his social media post Friday night whether a cap might take effect through executive action or legislation, though one Republican senator said he had spoken with the president and would work on a bill with his “full support.” Trump said he hoped it would be in place Jan. 20, one year after he took office.

Strong opposition is certain from Wall Street in addition to the credit card companies, which donated heavily to his 2024 campaign and have supported Trump's second-term agenda. Banks are making the argument that such a plan would most hurt poor people, at a time of economic concern, by curtailing or eliminating credit lines, driving them to high-cost alternatives like payday loans or pawnshops.

“We will no longer let the American Public be ripped off by Credit Card Companies that are charging Interest Rates of 20 to 30%,” Trump wrote on his Truth Social platform.

Researchers who studied Trump’s campaign pledge after it was first announced found that Americans would save roughly $100 billion in interest a year if credit card rates were capped at 10%. The same researchers found that while the credit card industry would take a major hit, it would still be profitable, although credit card rewards and other perks might be scaled back.

About 195 million people in the United States had credit cards in 2024 and were assessed $160 billion in interest charges, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau says. Americans are now carrying more credit card debt than ever, to the tune of about $1.23 trillion, according to figures from the New York Federal Reserve for the third quarter last year.

Further, Americans are paying, on average, between 19.65% and 21.5% in interest on credit cards according to the Federal Reserve and other industry tracking sources. That has come down in the past year as the central bank lowered benchmark rates, but is near the highs since federal regulators started tracking credit card rates in the mid-1990s. That’s significantly higher than a decade ago, when the average credit card interest rate was roughly 12%.

The Republican administration has proved particularly friendly until now to the credit card industry.

Capital One got little resistance from the White House when it finalized its purchase and merger with Discover Financial in early 2025, a deal that created the nation’s largest credit card company. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which is largely tasked with going after credit card companies for alleged wrongdoing, has been largely nonfunctional since Trump took office.

In a joint statement, the banking industry was opposed to Trump's proposal.

“If enacted, this cap would only drive consumers toward less regulated, more costly alternatives," the American Bankers Association and allied groups said.

Bank lobbyists have long argued that lowering interest rates on their credit card products would require the banks to lend less to high-risk borrowers. When Congress enacted a cap on the fee that stores pay large banks when customers use a debit card, banks responded by removing all rewards and perks from those cards. Debit card rewards only recently have trickled back into consumers' hands. For example, United Airlines now has a debit card that gives miles with purchases.

The U.S. already places interest rate caps on some financial products and for some demographics. The Military Lending Act makes it illegal to charge active-duty service members more than 36% for any financial product. The national regulator for credit unions has capped interest rates on credit union credit cards at 18%.

Credit card companies earn three streams of revenue from their products: fees charged to merchants, fees charged to customers and the interest charged on balances. The argument from some researchers and left-leaning policymakers is that the banks earn enough revenue from merchants to keep them profitable if interest rates were capped.

"A 10% credit card interest cap would save Americans $100 billion a year without causing massive account closures, as banks claim. That’s because the few large banks that dominate the credit card market are making absolutely massive profits on customers at all income levels," said Brian Shearer, director of competition and regulatory policy at the Vanderbilt Policy Accelerator, who wrote the research on the industry's impact of Trump's proposal last year.

There are some historic examples that interest rate caps do cut off the less creditworthy to financial products because banks are not able to price risk correctly. Arkansas has a strictly enforced interest rate cap of 17% and evidence points to the poor and less creditworthy being cut out of consumer credit markets in the state. Shearer's research showed that an interest rate cap of 10% would likely result in banks lending less to those with credit scores below 600.

The White House did not respond to questions about how the president seeks to cap the rate or whether he has spoken with credit card companies about the idea.

Sen. Roger Marshall, R-Kan., who said he talked with Trump on Friday night, said the effort is meant to “lower costs for American families and to reign in greedy credit card companies who have been ripping off hardworking Americans for too long."

Legislation in both the House and the Senate would do what Trump is seeking.

Sens. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., and Josh Hawley, R-Mo., released a plan in February that would immediately cap interest rates at 10% for five years, hoping to use Trump’s campaign promise to build momentum for their measure.

Hours before Trump's post, Sanders said that the president, rather than working to cap interest rates, had taken steps to deregulate big banks that allowed them to charge much higher credit card fees.

Reps. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., and Anna Paulina Luna, R-Fla., have proposed similar legislation. Ocasio-Cortez is a frequent political target of Trump, while Luna is a close ally of the president.

Seung Min Kim reported from West Palm Beach, Fla.

President Donald Trump arrives on Air Force One at Palm Beach International Airport, Friday, Jan. 9, 2025, in West Palm Beach, Fla. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

FILE - Visa and Mastercard credit cards are shown in Buffalo Grove, Ill., Feb. 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Nam Y. Huh, File)