LAGOS, Nigeria (AP) — About 20 children in shorts and vests gather at a swimming pool on a sweltering afternoon in Nigeria's economic hub of Lagos. A coach holds the hand of a boy who is blind as he demonstrates swimming motions and guides him through the pool while others take note.

It was one of the sessions with students of the Pacelli School for the Blind and Partially Sighted, where Emeka Chuks Nnadi, the swimming coach, uses his Swim in 1 Day, or SID, nonprofit to teach swimming to disabled children.

Click to Gallery

Swimming coach Emeka Chuks Nnadi teaches young, disabled students to swim as part of his Swim in 1 Day, or SID, nonprofit, in a pool at the Pacelli School for the Blind and Partially Sighted in Lagos, Nigeria, Wednesday, March 26, 2025. (AP Photo/Sunday Alamba)

Swimming coach Emeka Chuks Nnadi teaches disabled students to swim as part of his Swim in 1 Day, or SID, nonprofit program at a pool on the campus of the Pacelli School for the Blind and Partially Sighted in Lagos, Nigeria, Wednesday, March 26, 2025. (AP Photo/Sunday Alamba)

Swimming coach Emeka Chuks Nnadi teaches young, disabled students to swim as part of his Swim in 1 Day, or SID, nonprofit, in a pool at the Pacelli School for the Blind and Partially Sighted in Lagos, Nigeria, Wednesday, March 26, 2025. (AP Photo/Sunday Alamba)

Students of the Pacelli School for the Blind and Partially Sighted wait for the start of their swimming lesson at their schools' pool by swimming coach Emeka Chuks Nnadi as part of his Swim in 1 Day, or SID, nonprofit, in Lagos, Nigeria, Wednesday, March 26, 2025. (AP Photo/Sunday Alamba)

Swimming coach Emeka Chuks Nnadi teaches a disabled student to swim as part of his Swim in 1 Day, or SID, nonprofit, in a pool at the Pacelli School for the Blind and Partially Sighted in Lagos, Nigeria, Wednesday, March 26, 2025. (AP Photo/Sunday Alamba)

In a country where hundreds drown every year, often because of boat mishaps but sometimes as a result of domestic accidents, the initiative has so far taught at least 400 disabled people how to swim. It has also aided their personal development.

“It (has) helped me a lot, especially in class,” said 14-year-old Fikayo Adodo, one of Nnadi's trainees who is blind. “I am very confident now to speak with a crowd, with people. My brain is sharper, like very great."

The World Health Organization considers drowning as one of the leading causes of death through unintentional injury globally, with at least 300,000 people dying from drowning every year. The most at risk are young children.

Many of the deaths occur in African countries like Nigeria, with limited resources and training to avert such deaths.

In Nigeria — a country of more than 200 million people, 35 million of whom the government says are disabled — the challenge is far worse for disabled people who have less access to limited opportunities and resources in addition to societal stigma.

While the initiative is raising awareness among the children about drowning, it benefits wider society in different ways, Nnadi said, especially “if you want to have disabled people that are contributing to the economy and not just dependent on us as a society to take care of them.”

Nnadi recalled setting up the nonprofit after moving back to Nigeria from Spain in 2022 and seeing how disabled people are treated compared to others. It was a wide gap, he said, and thought that teaching them how to swim at a young age would be a great way to improve their lives.

“There is a thing in Africa where parents are ashamed of their (disabled) kids,” he said. “So (I am) trying to make people understand that your child that is blind could actually become a swimming superstar or a lawyer or doctor.”

“I find it rewarding (watching) them transform right under my eyes,” Nnadi said of the results of such lessons.

Watching them take their lessons, some struggle to stay calm in the water and stroke their way through it, but Nnadi and the two volunteers working with him patiently guide them through the water, often leaving them excited to quickly try again.

Some of them said that it gives them pleasure, while it is a lifesaving skill for some and it's therapy for others. Experts have also said that swimming can improve mental well-being, in addition to the physical benefits from exercising.

“Swimming (has) taught me to face my fears, it has (given) me boldness, it has given me courage, it has made me overcome my fears,” said 13-year-old Ikenna Goodluck, who is blind and among Nnadi’s trainees.

Ejiro Justina Obinwanne said that the initiative has helped her son Chinedu become more determined in life.

“He is selfless and determined to make something out of the lives of children that the world has written off in a lot of ways,” she said of Nnadi.

Swimming coach Emeka Chuks Nnadi teaches young, disabled students to swim as part of his Swim in 1 Day, or SID, nonprofit, in a pool at the Pacelli School for the Blind and Partially Sighted in Lagos, Nigeria, Wednesday, March 26, 2025. (AP Photo/Sunday Alamba)

Swimming coach Emeka Chuks Nnadi teaches disabled students to swim as part of his Swim in 1 Day, or SID, nonprofit program at a pool on the campus of the Pacelli School for the Blind and Partially Sighted in Lagos, Nigeria, Wednesday, March 26, 2025. (AP Photo/Sunday Alamba)

Swimming coach Emeka Chuks Nnadi teaches young, disabled students to swim as part of his Swim in 1 Day, or SID, nonprofit, in a pool at the Pacelli School for the Blind and Partially Sighted in Lagos, Nigeria, Wednesday, March 26, 2025. (AP Photo/Sunday Alamba)

Students of the Pacelli School for the Blind and Partially Sighted wait for the start of their swimming lesson at their schools' pool by swimming coach Emeka Chuks Nnadi as part of his Swim in 1 Day, or SID, nonprofit, in Lagos, Nigeria, Wednesday, March 26, 2025. (AP Photo/Sunday Alamba)

Swimming coach Emeka Chuks Nnadi teaches a disabled student to swim as part of his Swim in 1 Day, or SID, nonprofit, in a pool at the Pacelli School for the Blind and Partially Sighted in Lagos, Nigeria, Wednesday, March 26, 2025. (AP Photo/Sunday Alamba)

U.S. President Donald Trump says Iran has proposed negotiations after his threat to strike the Islamic Republic as an ongoing crackdown on demonstrators has led to hundreds of deaths.

Trump said late Sunday that his administration was in talks to set up a meeting with Tehran, but cautioned that he may have to act first as reports mount of increasing deaths and the government continues to arrest protesters.

“The meeting is being set up, but we may have to act because of what’s happening before the meeting. But a meeting is being set up. Iran called, they want to negotiate,” Trump told reporters on Air Force One on Sunday night.

Iran did not acknowledge Trump’s comments immediately. It has previously warned the U.S. military and Israel would be “legitimate targets” if America uses force to protect demonstrators.

The U.S.-based Human Rights Activists News Agency, which has accurately reported on past unrest in Iran, gave the death toll. It relies on supporters in Iran cross checking information. It said at least 544 people have been killed so far, including 496 protesters and 48 people from the security forces. It said more than 10,600 people also have been detained over the two weeks of protests.

With the internet down in Iran and phone lines cut off, gauging the demonstrations from abroad has grown more difficult. Iran’s government has not offered overall casualty figures.

The Latest:

A witness told the AP that the streets of Tehran empty at the sunset call to prayers each night.

Part of that stems from the fear of getting caught in the crackdown. Police sent the public a text message that warned: “Given the presence of terrorist groups and armed individuals in some gatherings last night and their plans to cause death, and the firm decision to not tolerate any appeasement and to deal decisively with the rioters, families are strongly advised to take care of their youth and teenagers.”

Another text, addressed “Dear parents,” which claimed to come from the intelligence arm of the paramilitary Revolutionary Guard, also directly warned people not to take part in demonstrations.

The witness spoke to the AP on condition of anonymity due to the ongoing crackdown.

—- By Jon Gambrell in Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Iran drew tens of thousands of pro-government demonstrators to the streets Monday in a show of power after nationwide protests challenging the country’s theocracy.

Iranian state television showed images of demonstrators thronging Tehran toward Enghelab Square in the capital.

It called the demonstration an “Iranian uprising against American-Zionist terrorism,” without addressing the underlying anger in the country over the nation’s ailing economy. That sparked the protests over two weeks ago.

State television aired images of such demonstrations around the country, trying to signal it had overcome the protests, as claimed by Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi earlier in the day.

China says it opposes the use of force in international relations and expressed hope the Iranian government and people are “able to overcome the current difficulties and maintain national stability.”

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning said Monday that Beijing “always opposes interference in other countries’ internal affairs, maintains that the sovereignty and security of all countries should be fully protected under international law, and opposes the use or threat of use of force in international relations.”

German Chancellor Friedrich Merz condemned “in the strongest terms the violence that the leadership in Iran is directing against its own people.”

He said it was a sign of weakness rather than strength, adding that “this violence must end.”

Merz said during a visit to India that the demonstrators deserve “the greatest respect” for the courage with which “they are resisting the disproportional, brutal violence of Iranian security forces.”

He said: “I call on the Iranian leadership to protect its population rather than threatening it.”

Iran’s Foreign Ministry spokesman on Monday suggested that a channel remained open with the United States.

Esmail Baghaei made the comment during a news conference in Tehran.

“It is open and whenever needed, through that channel, the necessary messages are exchanged,” he said.

However, Baghaei said such talks needed to be “based on the acceptance of mutual interests and concerns, not a negotiation that is one-sided, unilateral and based on dictation.”

The semiofficial Fars news agency in Iran, which is close to the paramilitary Revolutionary Guard, on Monday began calling out Iranian celebrities and leaders on social media who have expressed support for the protests over the past two weeks, especially before the internet was shut down.

The threat comes as writers and other cultural leaders were targeted even before protests. The news agency highlighted specific celebrities who posted in solidarity with the protesters and scolded them for not condemning vandalism and destruction to public property or the deaths of security forces killed during clashes. The news agency accused those celebrities and leaders of inciting riots by expressing their support.

Canada said it “stands with the brave people of Iran” in a statement on social media that strongly condemned the killing of protesters during widespread protests that have rocked the country over the past two weeks.

“The Iranian regime must halt its horrific repression and intimidation and respect the human rights of its citizens,” Canada’s government said on Monday.

Iran’s foreign minister claimed Monday that “the situation has come under total control” after a bloody crackdown on nationwide protests in the country.

Abbas Araghchi offered no evidence for his claim.

Araghchi spoke to foreign diplomats in Tehran. The Qatar-funded Al Jazeera satellite news network, which has been allowed to work despite the internet being cut off in the country, carried his remarks.

Iran’s foreign minister alleged Monday that nationwide protests in his nation “turned violent and bloody to give an excuse” for U.S. President Donald Trump to intervene.

Abbas Araghchi offered no evidence for his claim, which comes after over 500 have been reported killed by activists -- the vast majority coming from demonstrators.

Araghchi spoke to foreign diplomats in Tehran. The Qatar-funded Al Jazeera satellite news network, which has been allowed to work despite the internet being cut off in the country, carried his remarks.

Iran has summoned the British ambassador over protesters twice taking down the Iranian flag at their embassy in London.

Iranian state television also said Monday that it complained about “certain terrorist organization that, under the guise of media, spread lies and promote violence and terrorism.” The United Kingdom is home to offices of the BBC’s Persian service and Iran International, both which long have been targeted by Iran.

A huge crowd of demonstrators, some waving the flag of Iran, gathered Sunday afternoon along Veteran Avenue in LA’s Westwood neighborhood to protest against the Iranian government. Police eventually issued a dispersal order, and by early evening only about a hundred protesters were still in the area, ABC7 reported.

Los Angeles is home to the largest Iranian community outside of Iran.

Los Angeles police responded Sunday after somebody drove a U-Haul box truck down a street crowded with the the demonstrators, causing protesters to scramble out of the way and then run after the speeding vehicle to try to attack the driver. A police statement said one person was hit by the truck but nobody was seriously hurt.

The driver, a man who was not identified, was detained “pending further investigation,” police said in a statement Sunday evening.

Shiite Muslims hold placards and chant slogans during a protest against the U.S. and show solidarity with Iran in Lahore, Pakistan, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/K.M. Chaudary)

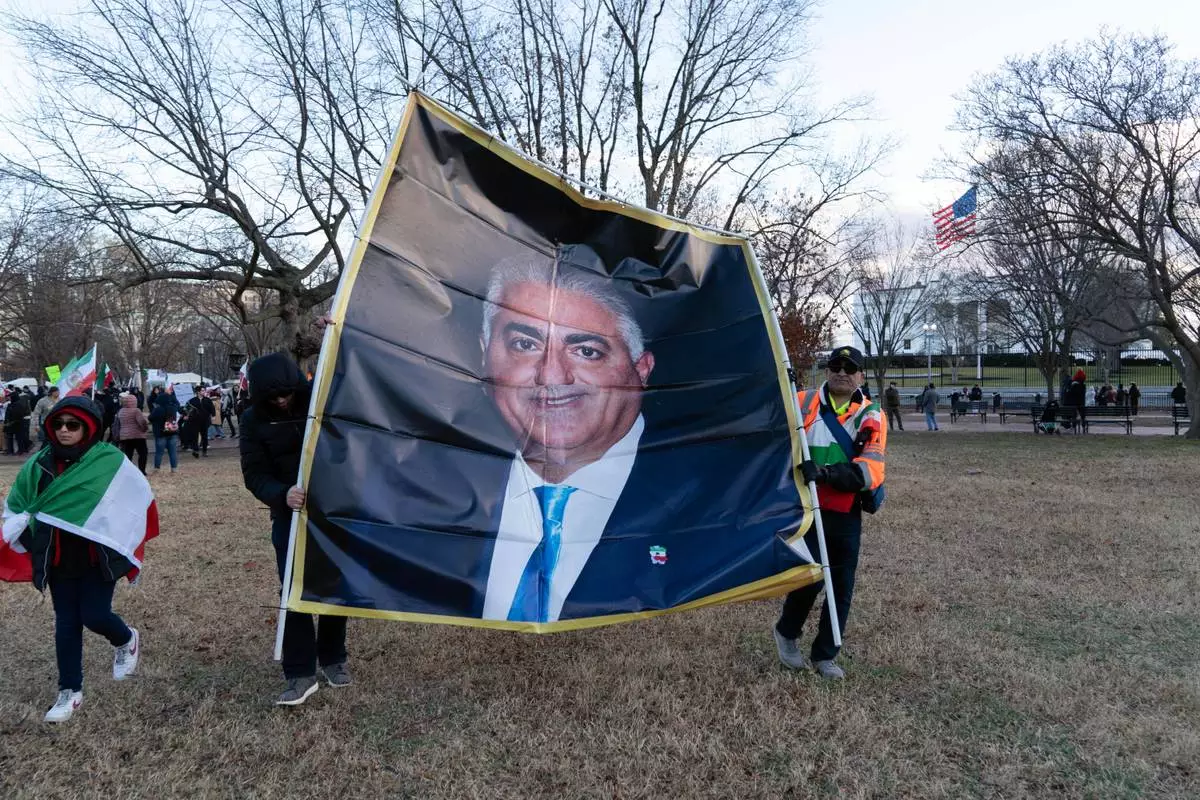

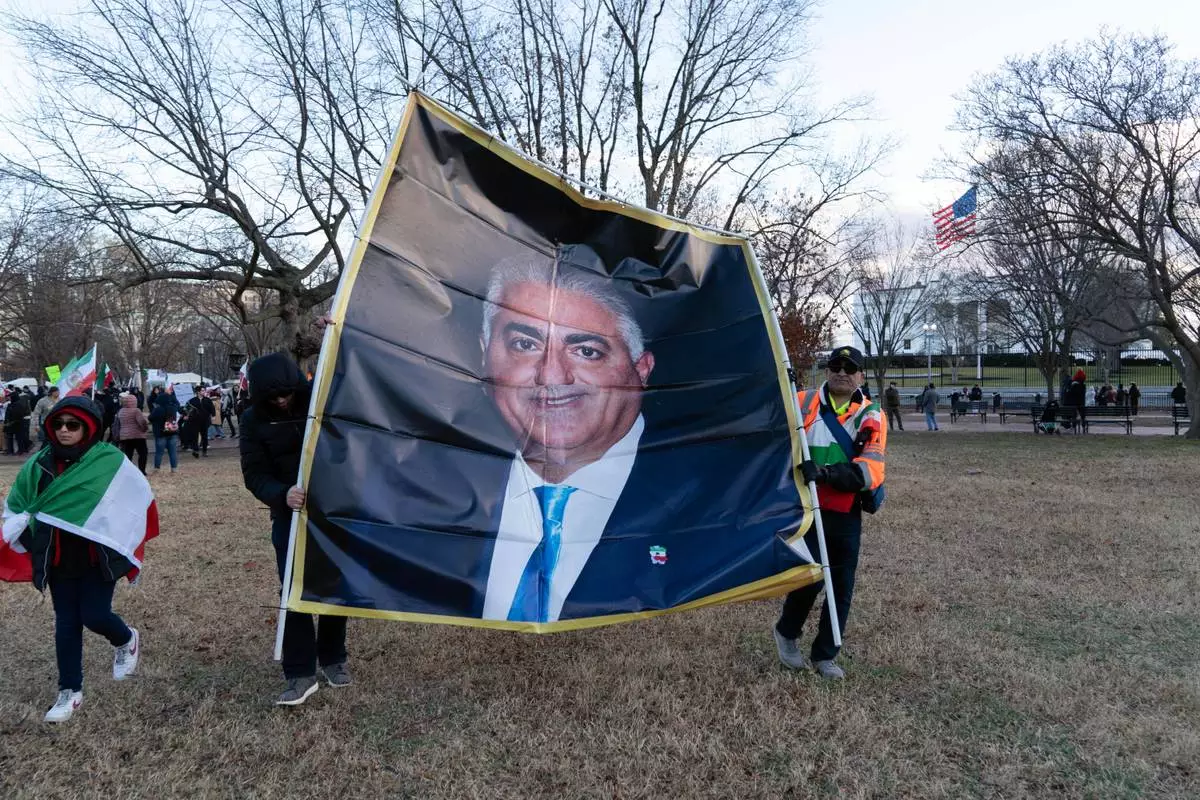

Activists carrying a photograph of Reza Pahlavi take part in a rally supporting protesters in Iran at Lafayette Park, across from the White House, in Washington, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

Activists take part in a rally supporting protesters in Iran at Lafayette Park, across from the White House in Washington, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

Protesters burn the Iranian national flag during a rally in support of the nationwide mass demonstrations in Iran against the government in Paris, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Michel Euler)