SOCOTRA, Yemen (AP) — On a windswept plateau high above the Arabian Sea, Sena Keybani cradles a sapling that barely reaches her ankle. The young plant, protected by a makeshift fence of wood and wire, is a kind of dragon’s blood tree — a species found only on the Yemeni island of Socotra that is now struggling to survive intensifying threats from climate change.

“Seeing the trees die, it’s like losing one of your babies,” said Keybani, whose family runs a nursery dedicated to preserving the species.

Click to Gallery

Ghost crab nests line the beach on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 22, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Socotra's Firmihin plateau, home to the largest remaining dragon's blood forest, is visible on Sept. 18, 2024, on the Yemeni island of Socotra. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

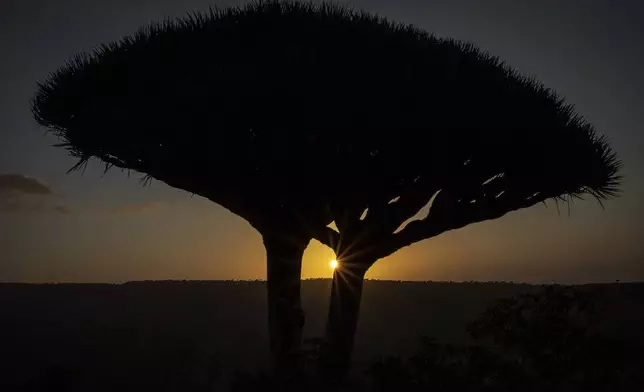

The sunrise appears between the branches of a dragon's blood tree on the Yemeni island of Socotra, on Sept. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Children play in the waves on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 22, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Sand dunes plunge into the sea on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

A fisherman drags a shark to shore on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Ecotourism guide Sami Mubarak poses for a portrait beneath an ailing dragon's blood tree on the Yemeni island of Socotra, Sept. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

A bottle tree grows from a cliff face on the Yemeni island of Socotra, Sept. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Achatinelloides mollusks gather on a tree's bark on the Yemeni island of Socotra, Sept. 22, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Mohammed Abdullah tends to dragon's blood tree saplings at the Keybani family nursery on the Yemeni island of Socotra, Sept. 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Goats roam amidst dragon's blood trees on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 18, 2024.(AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

A network of caves stretches for kilometers on the Yemeni island of Socotra, on Sept. 22, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Begonia socotrana grows on a rock on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

An Egyptian vulture soars above Socotra's Firmihin plateau on Sept. 18, 2024, on the Yemeni island of Socotra. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Toppled dragon's blood trees are strewn on the ground on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

A camel herder crosses the road on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 23, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

A dragon blood's tree sits above a canyon on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Frankincense and bottle trees grow on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Flowers blossom on a bottle tree on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Dragon's blood trees are seen from the highest peak on the Yemeni island of Socotra, Sept. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

A dragon blood's tree overlooks a natural infinity pool within Homhil Protected Area on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Known for their mushroom-shaped canopies and the blood-red sap that courses through their wood, the trees once stood in great numbers. But increasingly severe cyclones, grazing by invasive goats, and persistent turmoil in Yemen — which is one of the world’s poorest countries and beset by a decade-long civil war — have pushed the species, and the unique ecosystem it supports, toward collapse.

Often compared to the Galapagos Islands, Socotra floats in splendid isolation some 240 kilometers (150 miles) off the Horn of Africa. Its biological riches — including 825 plant species, of which more than a third exist nowhere else on Earth — have earned it UNESCO World Heritage status. Among them are bottle trees, whose swollen trunks jut from rock like sculptures, and frankincense, their gnarled limbs twisting skywards.

But it’s the dragon’s blood tree that has long captured imaginations, its otherworldly form seeming to belong more to the pages of Dr. Seuss than to any terrestrial forest. The island receives about 5,000 tourists annually, many drawn by the surreal sight of the dragon’s blood forests.

Visitors are required to hire local guides and stay in campsites run by Socotran families to ensure tourist dollars are distributed locally. If the trees were to disappear, the industry that sustains many islanders could vanish with them.

“With the income we receive from tourism, we live better than those on the mainland,” said Mubarak Kopi, Socotra’s head of tourism.

But the tree is more than a botanical curiosity: It’s a pillar of Socotra’s ecosystem. The umbrella-like canopies capture fog and rain, which they channel into the soil below, allowing neighboring plants to thrive in the arid climate.

“When you lose the trees, you lose everything — the soil, the water, the entire ecosystem,” said Kay Van Damme, a Belgian conservation biologist who has worked on Socotra since 1999.

Without intervention, scientists like Van Damme warn these trees could disappear within a few centuries — and with them many other species.

“We’ve succeeded, as humans, to destroy huge amounts of nature on most of the world’s islands,” he said. “Socotra is a place where we can actually really do something. But if we don’t, this one is on us.”

Across the rugged expanse of Socotra’s Firmihin plateau, the largest remaining dragon’s blood forest unfolds against the backdrop of jagged mountains. Thousands of wide canopies balance atop slender trunks. Socotra starlings dart among the dense crowns while Egyptian vultures bank against the relentless gusts. Below, goats weave through the rocky undergrowth.

The frequency of severe cyclones has increased dramatically across the Arabian Sea in recent decades, according to a 2017 study in the journal Nature Climate Change, and Socotra’s dragon’s blood trees are paying the price.

In 2015, a devastating one-two punch of cyclones — unprecedented in their intensity — tore across the island. Centuries-old specimens, some over 500 years old, which had weathered countless previous storms, were uprooted by the thousands. The destruction continued in 2018 with yet another cyclone.

As greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, so too will the intensity of the storms, warned Hiroyuki Murakami, a climate scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the study’s lead author. “Climate models all over the world robustly project more favorable conditions for tropical cyclones.”

But storms aren’t the only threat. Unlike pine or oak trees, which grow 60 to 90 centimeters (25 to 35 inches) per year, dragon’s blood trees creep along at just 2 to 3 centimeters (about 1 inch) annually. By the time they reach maturity, many have already succumbed to an insidious danger: goats.

An invasive species on Socotra, free-roaming goats devour saplings before they have a chance to grow. Outside of hard-to-reach cliffs, the only place young dragon’s blood trees can survive is within protected nurseries.

“The majority of forests that have been surveyed are what we call over-mature — there are no young trees, there are no seedlings,” said Alan Forrest, a biodiversity scientist at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh’s Centre for Middle Eastern Plants. “So you’ve got old trees coming down and dying, and there’s not a lot of regeneration going on.”

Keybani’s family's nursery is one of several critical enclosures that keep out goats and allow saplings to grow undisturbed.

“Within those nurseries and enclosures, the reproduction and age structure of the vegetation is much better,” Forrest said. “And therefore, it will be more resilient to climate change.”

But such conservation efforts are complicated by Yemen’s stalemated civil war. As the Saudi Arabia-backed, internationally recognized government battles Houthi rebels — a Shiite group backed by Iran — the conflict has spilled beyond the country’s borders. Houthi attacks on Israel and commercial shipping in the Red Sea have drawn retaliation from Israeli and Western forces, further destabilizing the region.

“The Yemeni government has 99 problems right now,” said Abdulrahman Al-Eryani, an advisor with Gulf State Analytics, a Washington-based risk consulting firm. “Policymakers are focused on stabilizing the country and ensuring essential services like electricity and water remain functional. Addressing climate issues would be a luxury.”

With little national support, conservation efforts are left largely up to Socotrans. But local resources are scarce, said Sami Mubarak, an ecotourism guide on the island.

Mubarak gestures toward the Keybani family nursery's slanting fence posts, strung together with flimsy wire. The enclosures only last a few years before the wind and rain break them down. Funding for sturdier nurseries with cement fence posts would go a long way, he said.

“Right now, there are only a few small environmental projects — it’s not enough,” he said. “We need the local authority and national government of Yemen to make conservation a priority.”

Follow Annika Hammerschlag on Instagram @ahammergram.

The Associated Press receives support from the Walton Family Foundation for coverage of water and environmental policy. The AP is solely responsible for all content. For all of AP’s environmental coverage, visit https://apnews.com/hub/climate-and-environment

Ghost crab nests line the beach on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 22, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Socotra's Firmihin plateau, home to the largest remaining dragon's blood forest, is visible on Sept. 18, 2024, on the Yemeni island of Socotra. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

The sunrise appears between the branches of a dragon's blood tree on the Yemeni island of Socotra, on Sept. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Children play in the waves on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 22, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Sand dunes plunge into the sea on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

A fisherman drags a shark to shore on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Ecotourism guide Sami Mubarak poses for a portrait beneath an ailing dragon's blood tree on the Yemeni island of Socotra, Sept. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

A bottle tree grows from a cliff face on the Yemeni island of Socotra, Sept. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Achatinelloides mollusks gather on a tree's bark on the Yemeni island of Socotra, Sept. 22, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Mohammed Abdullah tends to dragon's blood tree saplings at the Keybani family nursery on the Yemeni island of Socotra, Sept. 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Goats roam amidst dragon's blood trees on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 18, 2024.(AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

A network of caves stretches for kilometers on the Yemeni island of Socotra, on Sept. 22, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Begonia socotrana grows on a rock on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

An Egyptian vulture soars above Socotra's Firmihin plateau on Sept. 18, 2024, on the Yemeni island of Socotra. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Toppled dragon's blood trees are strewn on the ground on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

A camel herder crosses the road on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 23, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

A dragon blood's tree sits above a canyon on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Frankincense and bottle trees grow on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Flowers blossom on a bottle tree on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

Dragon's blood trees are seen from the highest peak on the Yemeni island of Socotra, Sept. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

A dragon blood's tree overlooks a natural infinity pool within Homhil Protected Area on the Yemeni island of Socotra on Sept. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Annika Hammerschlag)

A group of Buddhist monks and their rescue dog are striding single file down country roads and highways across the South, captivating Americans nationwide and inspiring droves of locals to greet them along their route.

In their flowing saffron and ocher robes, the men are walking for peace. It's a meditative tradition more common in South Asian countries, and it's resonating now in the U.S., seemingly as a welcome respite from the conflict, trauma and politics dividing the nation.

Their journey began Oct. 26, 2025, at a Vietnamese Buddhist temple in Texas, and is scheduled to end in mid-February in Washington, D.C., where they will ask Congress to recognize Buddha’s day of birth and enlightenment as a federal holiday. Beyond promoting peace, their highest priority is connecting with people along the way.

“My hope is, when this walk ends, the people we met will continue practicing mindfulness and find peace,” said the Venerable Bhikkhu Pannakara, the group’s soft-spoken leader who is making the trek barefoot. He teaches about mindfulness, forgiveness and healing at every stop.

Preferring to sleep each night in tents pitched outdoors, the monks have been surprised to see their message transcend ideologies, drawing huge crowds into churchyards, city halls and town squares across six states. Documenting their journey on social media, they — and their dog, Aloka — have racked up millions of followers online. On Saturday, thousands thronged in Columbia, South Carolina, where the monks chanted on the steps of the State House and received a proclamation from the city's mayor, Daniel Rickenmann.

At their stop Thursday in Saluda, South Carolina, Audrie Pearce joined the crowd lining Main Street. She had driven four hours from her village of Little River, and teared up as Pannakara handed her a flower.

“There’s something traumatic and heart-wrenching happening in our country every day,” said Pearce, who describes herself as spiritual, but not religious. “I looked into their eyes and I saw peace. They’re putting their bodies through such physical torture and yet they radiate peace.”

Hailing from Theravada Buddhist monasteries across the globe, the 19 monks began their 2,300 mile (3,700 kilometer) trek at the Huong Dao Vipassana Bhavana Center in Fort Worth.

Their journey has not been without peril. On Nov. 19, as the monks were walking along U.S. Highway 90 near Dayton, Texas, their escort vehicle was hit by a distracted truck driver, injuring two monks. One of them lost his leg, reducing the group to 18.

This is Pannakara's first trek in the U.S., but he's walked across several South Asian countries, including a 112-day journey across India in 2022 where he first encountered Aloka, an Indian Pariah dog whose name means divine light in Sanskrit.

Then a stray, the dog followed him and other monks from Kolkata in eastern India all the way to the Nepal border. At one point, he fell critically ill and Pannakara scooped him up in his arms and cared for him until he recovered. Now, Aloka inspires him to keep going when he feels like giving up.

“I named him light because I want him to find the light of wisdom,” Pannakara said.

The monk's feet are now heavily bandaged because he's stepped on rocks, nails and glass along the way. His practice of mindfulness keeps him joyful despite the pain from these injuries, he said.

Still, traversing the southeast United States has presented unique challenges, and pounding pavement day after day has been brutal.

“In India, we can do shortcuts through paddy fields and farms, but we can’t do that here because there are a lot of private properties,” Pannakara said. “But what’s made it beautiful is how people have welcomed and hosted us in spite of not knowing who we are and what we believe.”

In Opelika, Alabama, the Rev. Patrick Hitchman-Craig hosted the monks on Christmas night at his United Methodist congregation.

He expected to see a small crowd, but about 1,000 people showed up, creating the feel of a block party. The monks seemed like the Magi, he said, appearing on Christ’s birthday.

“Anyone who is working for peace in the world in a way that is public and sacrificial is standing close to the heart of Jesus, whether or not they share our tradition,” said Hitchman-Craig. “I was blown away by the number of people and the diversity of who showed up.”

After their night on the church lawn, the monks arrived the next afternoon at the Collins Farm in Cusseta, Alabama. Judy Collins Allen, whose father and brother run the farm, said about 200 people came to meet the monks — the biggest gathering she’s ever witnessed there.

“There was a calm, warmth and sense of community among people who had not met each other before and that was so special,” she said.

Long Si Dong, a spokesperson for the Fort Worth temple, said the monks, when they arrive in Washington, plan to seek recognition of Vesak, the day which marks the birth and enlightenment of the Buddha, as a national holiday.

“Doing so would acknowledge Vesak as a day of reflection, compassion and unity for all people regardless of faith,” he said.

But Pannakara emphasized that their main goal is to help people achieve peace in their lives. The trek is also a separate endeavor from a $200 million campaign to build towering monuments on the temple’s 14-acre property to house the Buddha’s teachings engraved in stone, according to Dong.

The monks practice and teach Vipassana meditation, an ancient Indian technique taught by the Buddha himself as core for attaining enlightenment. It focuses on the mind-body connection — observing breath and physical sensations to understand reality, impermanence and suffering. Some of the monks, including Pannakara, walk barefoot to feel the ground directly and be present in the moment.

Pannakara has told the gathered crowds that they don't aim to convert people to Buddhism.

Brooke Schedneck, professor of religion at Rhodes College in Memphis, Tennessee, said the tradition of a peace walk in Theravada Buddhism began in the 1990s when the Venerable Maha Ghosananda, a Cambodian monk, led marches across war-torn areas riddled with landmines to foster national healing after civil war and genocide in his country.

“These walks really inspire people and inspire faith,” Schedneck said. “The core intention is to have others watch and be inspired, not so much through words, but through how they are willing to make this sacrifice by walking and being visible.”

On Thursday, Becki Gable drove nearly 400 miles (about 640 kilometers) from Cullman, Alabama, to catch up with them in Saluda. Raised Methodist, Gable said she wanted some release from the pain of losing her daughter and parents.

“I just felt in my heart that this would help me have peace,” she said. “Maybe I could move a little bit forward in my life.”

Gable says she has already taken one of Pannakara’s teachings to heart. She’s promised herself that each morning, as soon as she awakes, she’d take a piece of paper and write five words on it, just as the monk prescribed.

“Today is my peaceful day.”

Freelance photojournalist Allison Joyce contributed to this report.

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

Buddhist monks who are participating in the, "Walk For Peace," get lunch Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Aloka rests with Buddhist monks who are participating in the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

A sign is seen greeting the Buddhist monks who are participating in the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Supporters pray with Buddhist monks who are participating in the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Supporters watch Buddhist monks who are participating in the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

A Buddhist monk ties a prayer bracelet around the wrist of Josey Lee, 2-months-old, during the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Bhikkhu Pannakara, a spiritual leader, speaks to supporters during the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Buddhist monks participate in the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Buddhist monks participate in the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Bhikkhu Pannakara leads other buddhist monks in the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Audrie Pearce greets Buddhist monks who are participating in the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Bhikkhu Pannakara, a spiritual leader, speaks to supporters during the, "Walk For Peace," Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Buddhist monks who are participating in the, "Walk For Peace," arrive in Saluda, Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)

Buddhist monks who are participating in the, "Walk For Peace," are seen with their dog, Aloka, Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026, in Saluda, S.C. (AP Photo/Allison Joyce)