SAYYIDA ZEINAB, Syria (AP) — At the Sayyida Zeinab shrine, rituals of faith unfold: worshippers kneel in prayer, visitors raise their palms skyward or fervently murmur invocations as they press their faces against an ornate structure enclosing where they believe the granddaughter of Prophet Muhammad is entombed.

But it’s more than just religious devotion that the golden-domed shrine became known for during Syria’s prolonged civil war.

At the time, the shrine's protection from Sunni extremists became a rallying cry for some Shiite fighters and Iran-backed groups from beyond Syria’s borders who backed the former government of Bashar Assad. The shrine and the surrounding area, which bears the same name, thus emerged as examples of how the religious and political increasingly intertwined during the conflict.

With such a legacy, local Shiite community leaders and members are now navigating a dramatically altered political landscape around Sayyida Zeinab and beyond, after Assad’s December ouster by armed insurgents led by the Sunni Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). The complex transition that is underway has left some in Syria’s small Shiite minority feeling vulnerable.

“For Shiites around the world, there’s huge sensitivity surrounding the Sayyida Zeinab Shrine,” said Hussein al-Khatib. “It carries a lot of symbolism.”

After Assad’s ouster, al-Khatib joined other Syrian Shiite community members to protect the shrine from the inside. The new security forces guard it from the outside.

“We don’t want any sedition among Muslims,” he said. “This is the most important message, especially in this period that Syria is going through.”

Zeinab is a daughter of the first Shiite imam, Ali, cousin and son-in-law of Prophet Muhammad; she's especially revered among Shiites as a symbol of steadfastness, patience and courage.

She has several titles, such as the “mother of misfortunes” for enduring tragedies, including the 7th-century killing of her brother, Hussein. His death exacerbated the schism between Islam’s two main sects, Sunni and Shiite, and is mourned annually by Shiites.

Zeinab's burial place is disputed; some Muslims believe it’s elsewhere. The Syria shrine has drawn pilgrims, including from Iran, Iraq and Lebanon. Since Assad’s ouster, however, fewer foreign visitors have come, an economic blow to those catering to them in the area.

Over the years, the Sayyida Zeinab area has suffered deadly attacks by militants.

In January, state media reported that intelligence officials in Syria’s post-Assad government thwarted a plan by the Islamic State group to set off a bomb at the shrine. The announcement appeared to be an attempt by Syria’s new leaders to reassure religious minorities, including those seen as having supported Assad’s former government.

Al-Khatib, who moved his family from Aleppo province to the Sayyida Zeinab area shortly before Assad’s fall, said Assad had branded himself as a protector of minorities. “When killings, mobilization ... and sectarian polarization began," the narrative "of the regime and its allies was that ‘you, as a Shiite, you as a minority member, will be killed if I fall.’”

The involvement of Sunni jihadis and some hardline foreign Shiite fighters fanned sectarian flames, he said.

The Syria conflict began as one of several uprisings against Arab dictators before Assad brutally crushed what started as largely peaceful protests and a civil war erupted. It became increasingly fought along sectarian lines, drew in foreign fighters and became a proxy battlefield for regional and international powers on different sides.

Recently, a red flag reading “Oh, Zeinab" that had fluttered from its dome was removed after some disparaged it as a sectarian symbol.

Sheikh Adham al-Khatib, a representative of followers of the Twelver branch of Shiism in Syria, said such flags “are not directed against anyone,” but that it was agreed to remove it for now to keep the peace.

“We don’t want a clash to happen. We see that ... there’s sectarian incitement, here and there," he said.

Earlier, Shiite leaders had wrangled with some endowments ministry officials over whether the running of the shrine would stay with the Shiite endowment trustee as it’s been, he said, adding “we've rejected" changing the status quo. No response was received before publication to questions sent to a Ministry of Endowments media official.

Adham al-Khatib and other Shiite leaders recently met with Syrian President Ahmad al-Sharaa.

“We’ve talked transparently about some of the transgressions,” he said. “He promised that such matters would be handled but that they require some patience because of the negative feelings that many harbor for Shiites as a result of the war.”

Many, the sheikh said, “are holding the Shiites responsible for prolonging the regime’s life.” This “is blamed on Iran, on Hezbollah and on Shiites domestically," he said, adding that he believes the conflict was political rather than religious.

Early in the conflict, he said, “our internal Shiite decision was to be neutral for long months.” But, he said, there was sectarian incitement against Shiites by some and argued that “when weapons, kidnappings and killing of civilians started, Shiites were forced to defend themselves.”

Regionally, Assad was backed by Iran and the Shiite militant Lebanese group Hezbollah, whose intervention helped prop up his rule. Most rebels against him were Sunni, as were their patrons in the region.

Besides the shrine's protection argument, geopolitical interests and alliances were at play as Syria was a key part of Iran’s network of deterrence against Israel.

Today, rumors and some social media posts can threaten to inflame emotions.

Shrine director Jaaffar Kassem said he received a false video purporting to show the shrine on fire and was flooded with calls about it.

At the shrine, Zaher Hamza said he prays “for safety and security” and the rebuilding of “a modern Syria, where there’s harmony among all and there are no grudges or injustice.”

Is he worried about the shrine? “We’re the ones who are in the protection of Sayyida Zeinab — not the ones who will protect the Sayyida Zeinab," he replied.

While some Shiites have fled Syria after Assad’s fall, Hamza said he wouldn’t.

“Syria is my country,” he said. “If I went to Lebanon, Iraq or to European countries, I’d be displaced. I’ll die in my country.”

Some are less at ease.

Small groups of women gathered recently at the Sayyida Zeinab courtyard, chatting among themselves in what appeared to be a quiet atmosphere. Among them was Kamla Mohamed.

Early in the war, Mohamed said, her son was kidnapped more than a decade ago by anti-government rebels for serving in the military. The last time she saw him, she added, was on a video where he appeared with a bruised face.

When Assad fell, Mohamed feared for her family.

Those fears were fueled by the later eruption of violence in Syria’s coastal region, where a counteroffensive killed many Alawite civilians — members of the minority sect from which Assad hails and drew support as he ruled over a Sunni majority. Human rights groups reported revenge killings against Alawites; the new authorities said they were investigating.

“We were scared that people would come to us and kill us,” Mohamed said, clutching a prayer bead. “Our life has become full of fear.”

Another Syrian Shiite shrine visitor said she's been feeling on edge. She spoke on condition she only be identified as Umm Ahmed, or mother of Ahmed, as is traditional, for fear of reprisals against her or her family.

She said, speaking shortly after the coastal violence in March, that she’s thought of leaving the country, but added that there isn’t enough money and she worries that her home would be stolen if she did. Still, “one’s life is the most precious,” she said.

She hopes it won’t come to that.

“Our hope in God is big,” she said. “God is the one protecting this area, protecting the shrine and protecting us.”

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

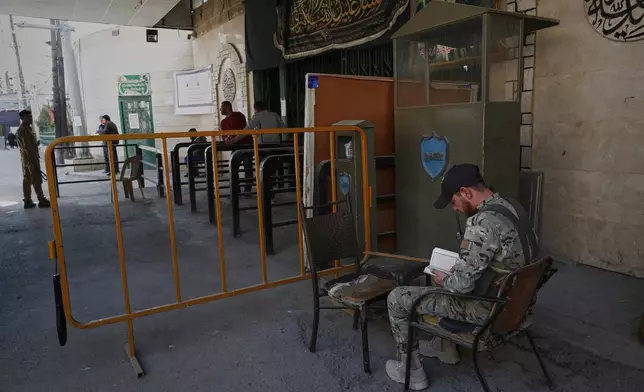

A soldier from the Syrian government army reads the Quran, the Muslim holy book, at a checkpoint near the Sayyida Zeinab Shrine, where many Shiite Muslims believe Zeinab, the granddaughter of the Prophet Muhammad, is buried, in Sayyida Zeinab, south of Damascus, Syria, Saturday, March 15, 2025. (AP Photo/Omar Sanadiki)

Shiite worshipers arrive at the Sayyida Zeinab Shrine, where they believe Zeinab, the granddaughter of Prophet Muhammad, is entombed, in Sayyida Zeinab, south of Damascus, Syria, Saturday, March 15, 2025. (AP Photo/Omar Sanadiki)

A man sits next to a copy of the Quran at the Sayyida Zeinab Shrine, where many Shiite Muslims believe Zeinab, the granddaughter of Prophet Muhammad, is entombed, in Sayyida Zeinab, south of Damascus, Syria, Saturday, March 15, 2025. (AP Photo/Omar Sanadiki)

Shiite clergy speak at the Sayyida Zeinab Shrine, where many Shiite Muslims believe Zeinab, the granddaughter of Prophet Muhammad, is entombed, in Sayyida Zeinab, south of Damascus, Syria, Saturday, March 15, 2025. (AP Photo/Omar Sanadiki)

Shiite worshippers pray at the Sayyida Zeinab shrine where many Shiite Muslims believe Zeinab, the granddaughter of Prophet Muhammad is entombed, in Sayyida Zeinab, south of Damascus, Syria, Saturday March 15, 2025.(AP Photo/Omar Sanadiki)

Worshippers pray at the Sayyida Zeinab shrine where many Shiite believe Zeinab, the granddaughter of Prophet Muhammad is entombed, in Sayyida Zeinab, south of Damascus, Syria, Saturday March 15, 2025.(AP Photo/Omar Sanadiki