SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — A 72-year-old mother has filed a lawsuit against South Korea’s government and its largest adoption agency, alleging systematic failures in her forced separation from her toddler son who was sent to Norway without her consent.

Choi Young-ja searched desperately for her son for nearly five decades before their emotional reunion in 2023.

The damage claim by Choi, whose story was part of an Associated Press investigation also documented by Frontline (PBS), comes as South Korea faces growing pressure to address the extensive fraud and abuse that tainted its historic foreign adoption program.

In a landmark report in March, South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission concluded that the government bears responsibility for facilitating an aggressive and loosely regulated foreign adoption program that carelessly or unnecessarily separated thousands of children from their families for multiple generations.

It found that the country’s past military governments were driven by efforts to reduce welfare costs and empowered private agencies to speed up adoptions, while turning a blind eye to widespread practices that often manipulated children’s backgrounds and origins, leading to an explosion in adoptions that peaked in the 1970s and 1980s.

Children who had living parents, including those who were simply missing or kidnapped, were often falsely documented as abandoned orphans to increase their chances of being adopted in Western countries, which have taken in around 200,000 Korean children over the past seven decades.

Choi’s lawsuit follows a similar case filed in October by another woman in her 70s, Han Tae-soon, who also sued the government and Holt Children’s Services over the adoption of her daughter who was sent to the United States in 1976, months after she was kidnapped at age 4.

Choi says her son, who was 3 years old at the time, ran out of their home in Seoul in July 1975 to chase a cloud of insecticide sprayed by a fumigation truck while playing with friends — and never came back. She and her late husband spent years searching for him, scouring police stations in and around Seoul, and regularly bringing posters with his name and photo to Holt, South Korea’s largest adoption agency. They were repeatedly told there was no information.

After decades of searching in vain, Choi made a final effort by submitting her DNA to a police unit that helps reunite adoptees with birth families. In 2023, she discovered through 325Kamra, a volunteer group helping adoptees find birth families using DNA, that her son had been adopted to Norway in December 1975, only five months after he went missing. The adoption had been handled by Holt, the very agency she had visited countless times, under a different name and photograph.

Enraged, Choi confronted Holt and has since worked with lawyers to prepare a lawsuit against the agency, the South Korean government, and an orphanage in the city of Suwon where her son stayed before being transferred to Holt. Her now 52-year-old son, who traveled to South Korea in 2023 to meet her, has declined to comment on the story.

The 550 million won ($403,000) civil suit recently filed with the Seoul Central District Court alleges that the government failed in its legal duty to identify Choi’s son after he arrived at an orphanage — despite her immediate police report — and to verify his guardianship as he was processed through a state-controlled foreign adoption system.

The orphanage and Holt failed to verify the child’s status or notify his parents, even though Choi’s son was old enough to speak and showed obvious signs of having a family. In particular, Holt falsified records to describe him as an abandoned orphan — even though Choi had visited the agency looking for him while he was in its custody, before the flight to Norway, according to Jeon Min Kyeong, one of Choi’s lawyers.

Holt hasn't responded to AP’s repeated requests to comment on Choi’s case. South Korea’s Justice Ministry, which represents the government in lawsuits, said it cannot comment on an ongoing case.

Choi and Han are the first known birth parents to sue the South Korean government and an adoption agency over the allegedly illegal adoptions of their children.

In 2019, Adam Crapser became the first Korean adoptee to sue the Korean government and an adoption agency — Holt — accusing them of mishandling his adoption to the United States, where he endured an abusive childhood, faced legal troubles, and was eventually deported in 2016. But the Seoul High Court in January cleared both the government and Holt of all liability, overturning a lower court ruling that had ordered the agency to pay damages for failing to inform his adoptive parents of the need to take additional steps to secure his U.S. citizenship.

The truth commission’s findings, released in March, could possibly inspire more adoptees or birth parents to seek damages against the government and adoption agencies. However, some adoptees criticized the cautiously worded report, arguing that it should have more forcefully acknowledged the government’s complicity and offered more concrete recommendations for reparations for victims of illegal adoption.

During the March news conference, the commission’s chairperson, Park Sun Young, responded to a plea by Yooree Kim, who was sent to a couple in France at age 11 by Holt without her biological parents’ consent, by vowing to strengthen the recommendations. However, the commission didn't follow up before the final version of the report was delivered to adoptees last week.

The commission’s investigation deadline expired Monday, after it confirmed human rights violations in just 56 of the 367 complaints filed by adoptees since 2022. It had suspended its adoption investigation in April following internal disputes among progressive- and conservative-leaning commissioners over which cases warranted recognition as problematic.

The fate of the remaining 311 cases, either deferred or incompletely reviewed, now hinges on whether lawmakers will establish a new truth commission through legislation during Seoul’s next government, which takes office after the presidential election on June 3.

The government has so far ignored the commission’s recommendation to issue an official apology to adoptees.

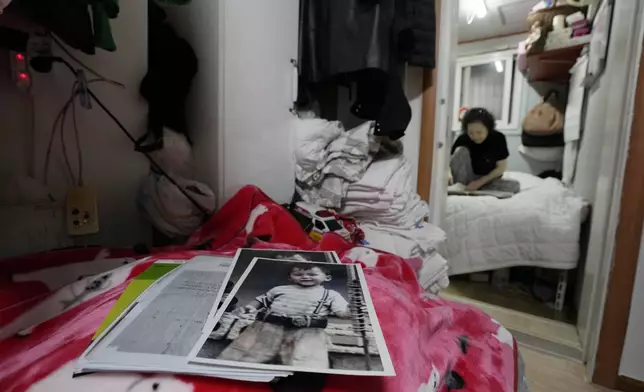

FILE - Photos of Choi Young-ja's son, Paik Sang-yeol, who went missing in 1975, sit on a bed in her motel room in Seoul, South Korea, Tuesday, March 5, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon, File)

FILE - Yooree Kim, who was 11 when she was sent by an adoption agency to a couple in France, sits for a portrait as tears well up in her eyes in her apartment in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, May 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong, File)

FILE - Truth and Reconciliation Commission Chairperson Park Sun Young, right, comforts adoptee Yooree Kim during a press conference in Seoul, South Korea, March 26, 2025. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon, File)

FILE - Choi Young-ja holds a smartphone displaying a photo of her son, who went missing in 1975, as she sits in her motel room in Seoul, South Korea, Tuesday, March 5, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon, File)

FILE - Choi Young-ja holds a photo of her son, who went missing in 1975, in her motel room in Seoul, South Korea, March 5, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon, File)