NEW YORK (AP) — Former U.S. Rep. Charles Rangel of New York, an outspoken, gravel-voiced Harlem Democrat who spent nearly five decades on Capitol Hill and was a founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus, died Monday at age 94.

His family confirmed the death in a statement provided by City College of New York spokesperson Michelle Stent. He died at a hospital in New York, Stent said.

Click to Gallery

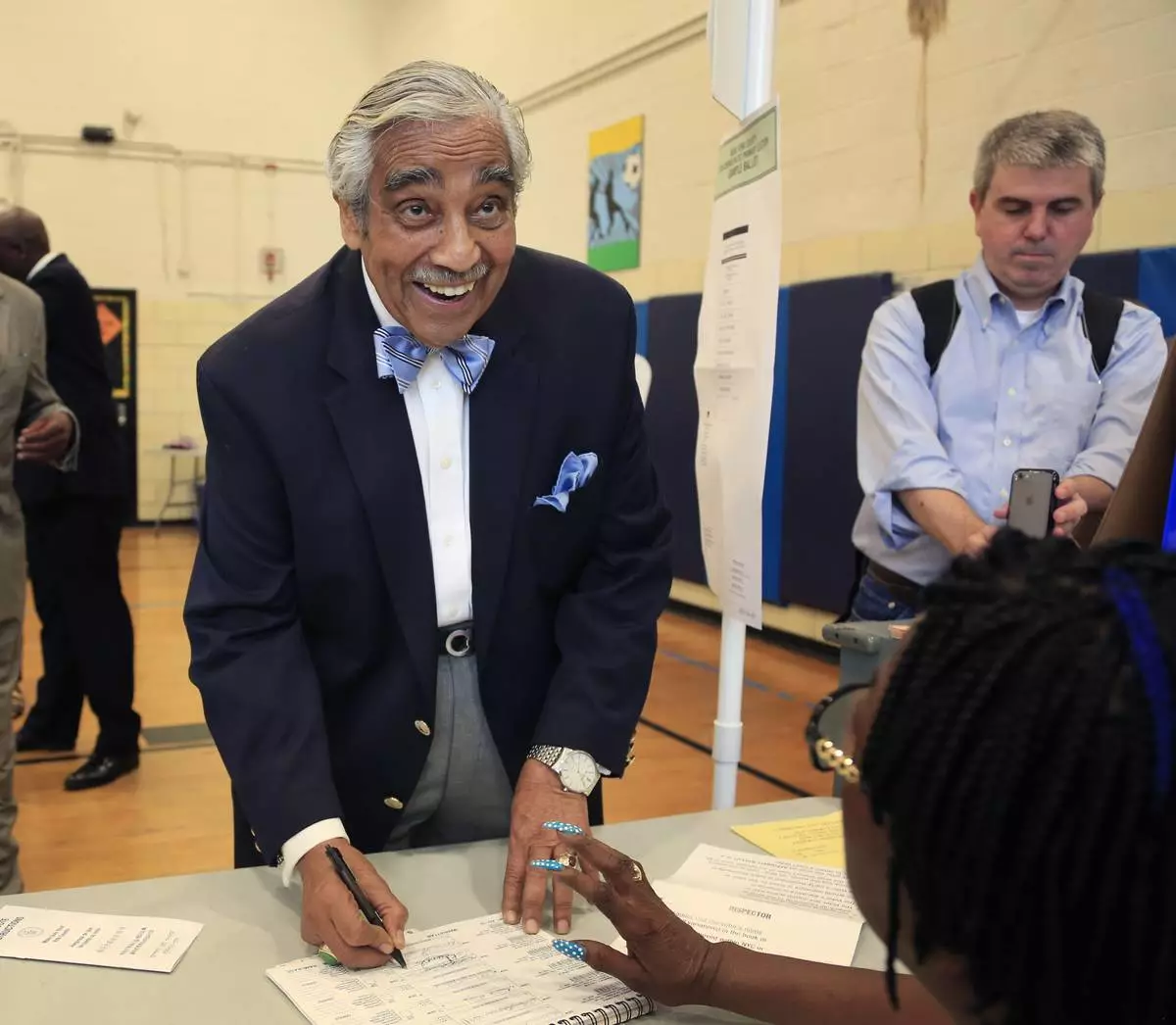

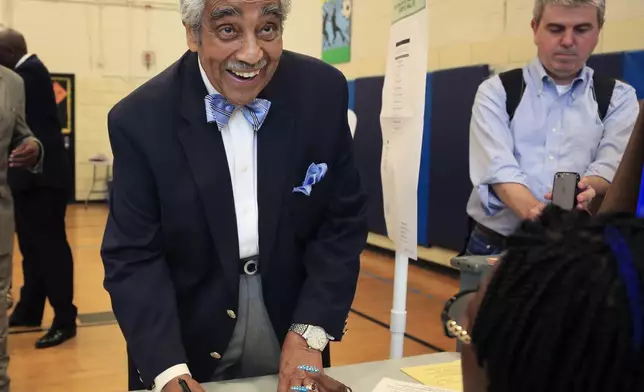

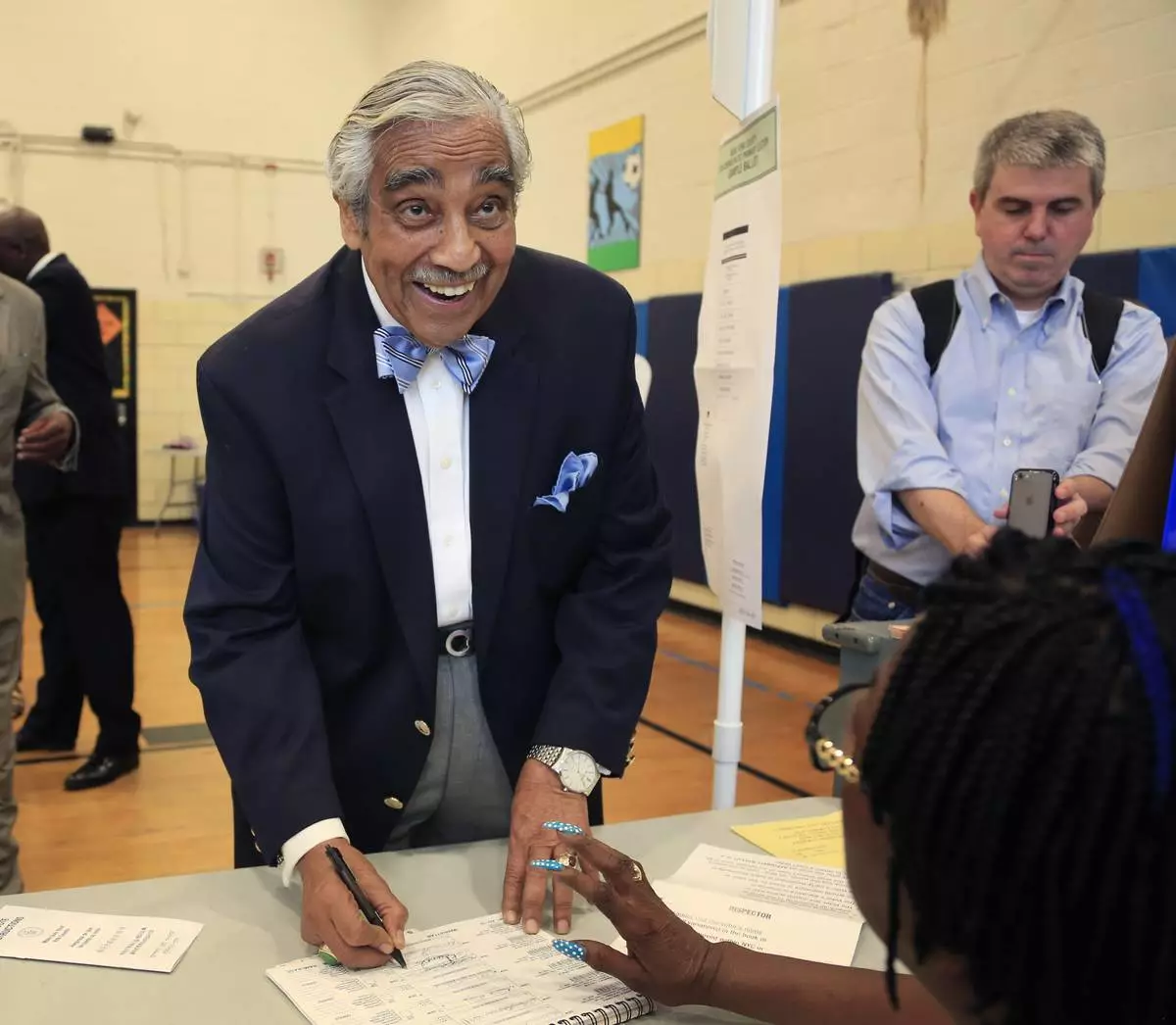

FILE - Harlem Rep. Charles Rangel looks up at reporters while voting in New York, June 28, 2016. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig, File)

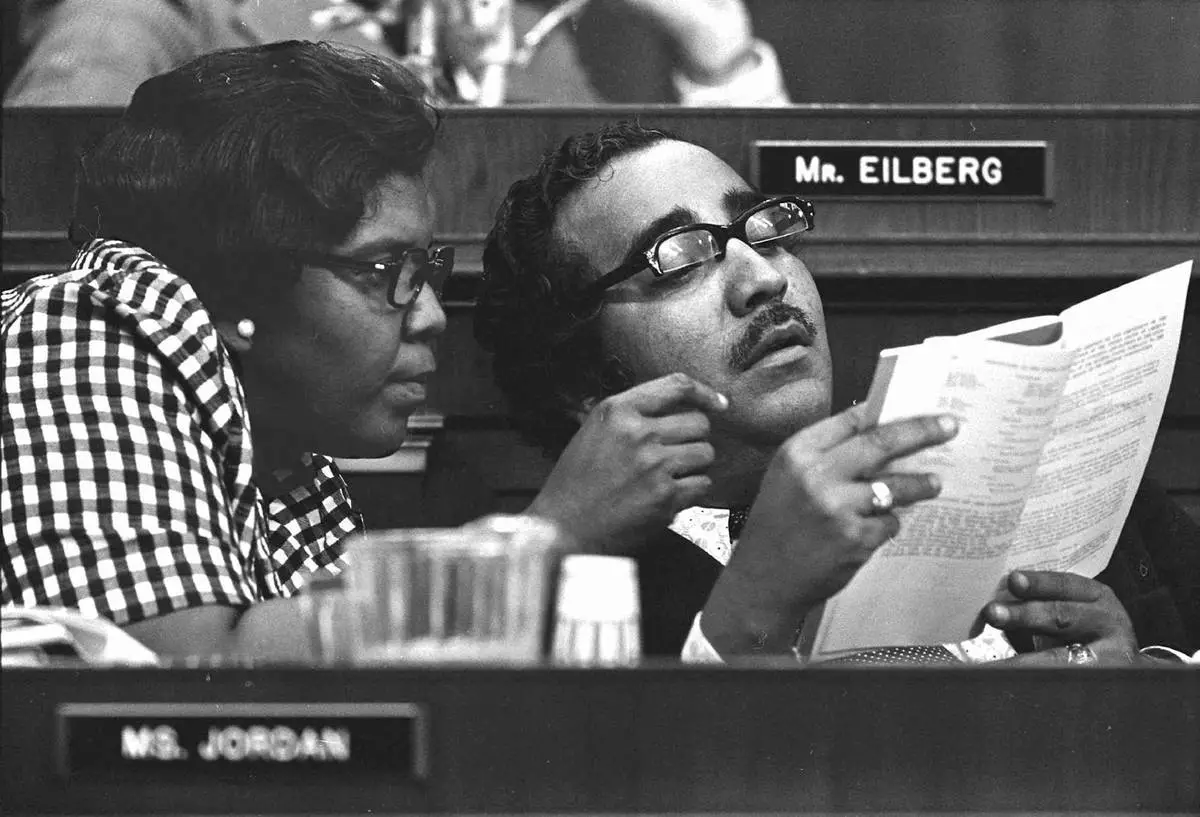

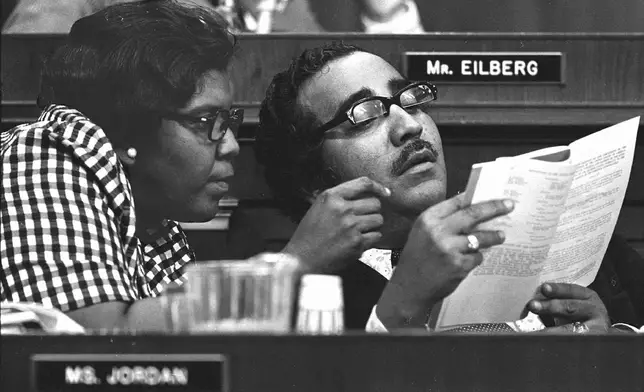

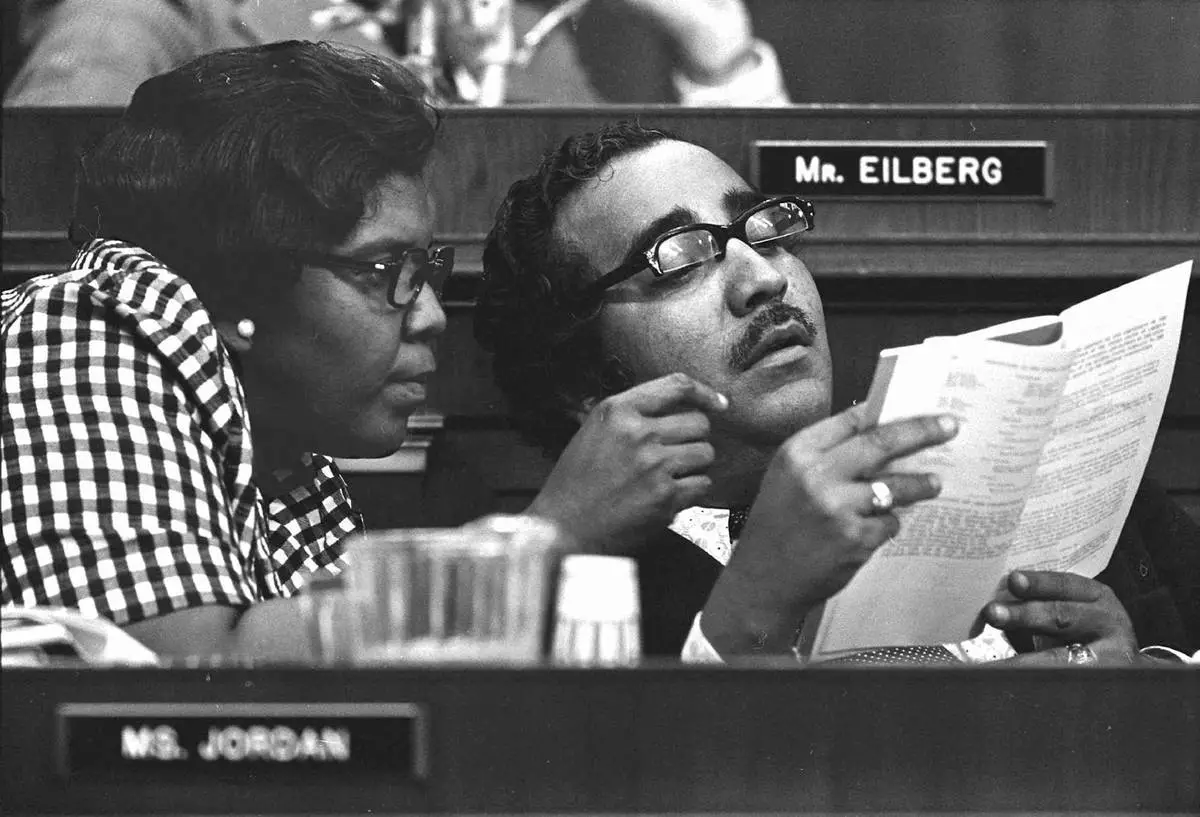

FILE - In this July 26, 1974 file photo, Reps. Charles Rangel, D-N.Y., and Barbara Jordan, D-Tex., left, look over a copy of the Constitution during a House Judiciary Committee debate on articles of impeachment for President Richard Nixon in Washington, D.C. (AP Photo/File)

FILE - Congressman Charles Rangel leaves a rally for airport workers at LaGuardia Airport in the Queens borough of New York, June 26, 2014. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig, File)

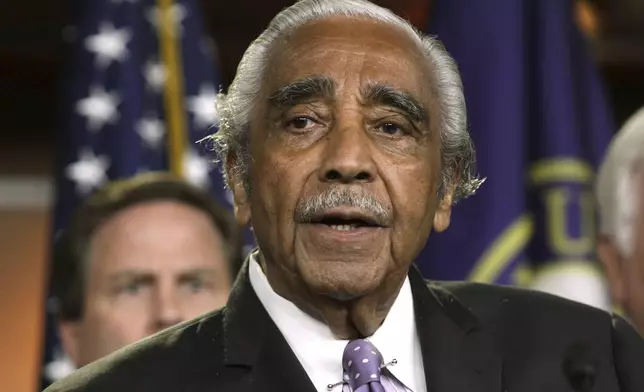

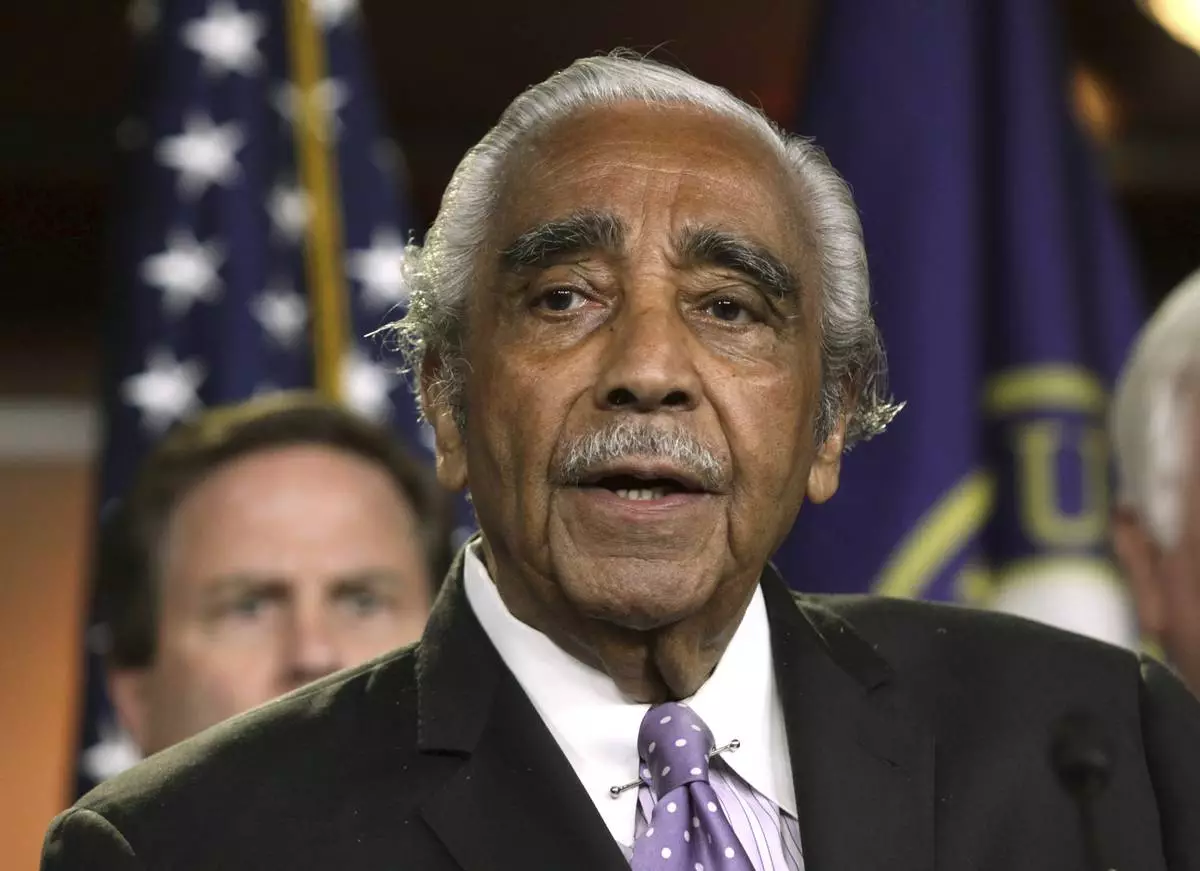

FILE - In this June 16, 2016 file photo, Rep. Charles Rangel, D-N.Y., speaks at a news conference on Capitol Hill in Washington. Rangel retires after more than four decades in office. (AP Photo/Lauren Victoria Burke, File)

A veteran of the Korean War, he defeated legendary Harlem politician Adam Clayton Powell in 1970 to start his congressional career. During the next 40-plus years, he became a legend himself as dean of the New York congressional delegation and, in 2007, the first African American to chair the powerful Ways and Means Committee.

He stepped down from that committee amid an ethics cloud, and the House censured him in 2010. But he continued to serve in Congress until his retirement in 2017.

Rangel was the last surviving member of the Gang of Four — African American political figures who wielded great power in New York City and state politics. The others were David Dinkins, New York City’s first Black mayor; Percy Sutton, who was Manhattan Borough president; and Basil Paterson, a deputy mayor and New York secretary of state.

“Charlie was a true activist — we’ve marched together, been arrested together and painted crack houses together,” the Rev. Al Sharpton, leader of the National Action Network, said in a statement, noting that he met Rangel as a teenager.

House Democratic Leader Hakeem Jeffries of New York issued a statement calling Rangel “a patriot, hero, statesman, leader, trailblazer, change agent and champion for justice who made his beloved Harlem, the City of New York and the United States of America a better place for all."

Few could forget Rangel after hearing him talk. His distinctive gravel-toned voice and wry sense of humor were a memorable mix.

That voice — one of the most liberal in the House — was loudest in opposition to the Iraq War, which he branded a “death tax” on poor people and minorities. In 2004, he tried to end the war by offering a bill to restart the military service draft. Republicans called his bluff and brought the bill to a vote. Even Rangel voted against it.

A year later, Rangel’s fight over the war became bitterly personal with then-Vice President Dick Cheney.

Rangel said Cheney, who has a history of heart trouble, might be too sick to perform his job.

“I would like to believe he’s sick rather than just mean and evil,” Rangel said. After several such verbal jabs, Cheney hit back, saying Rangel was “losing it.”

The charismatic Harlem lawmaker rarely backed down from a fight after he first entered the House in 1971 as a dragon slayer of sorts, having unseated Powell in the Democratic congressional primary in 1970. The flamboyant elder Powell, a city political icon first elected to the House in 1944, was ill and haunted by scandal at the time.

In 1987, Congress approved what was known as the “Rangel amendment," which denied foreign tax credits to U.S. companies investing in apartheid-era South Africa.

Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton noted that he urged her to run for the Senate in 2000. Former President Bill Clinton recalled working with Rangel in the 1990s to extend tax credits for businesses that invest in economically distressed areas.

Rangel became leader of the main tax-writing committee of the House, which has jurisdiction over programs including Social Security and Medicare, after the 2006 midterm elections when Democrats ended 12 years of Republican control of the chamber. But in 2010, a House ethics committee conducted a hearing on 13 counts of alleged financial and fundraising misconduct over issues surrounding financial disclosures and use of congressional resources.

He was convicted of 11 ethics violations. The House found he had failed to pay taxes on a vacation villa, filed misleading financial disclosure forms and improperly solicited donations for a college center from corporations with business before his committee.

The House followed the ethics committee’s recommendation that he be censured, the most serious punishment short of expulsion.

Rangel looked after his constituents, sponsoring empowerment zones with tax credits for businesses moving into economically depressed areas and developers of low income housing.

“I have always been committed to fighting for the little guy,” Rangel said in 2012.

Rangel was born June 11, 1930. During the Korean War, he earned a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star. He would always say that he measured his days, even the troubled ones around the ethics scandal, against the time in 1950 when he survived being wounded as other soldiers didn’t make it.

It became the title of his autobiography: “And I Haven’t Had A Bad Day Since.”

A high school dropout, he went to college on the G.I. Bill, getting degrees from New York University and St. John’s University Law School.

FILE - Harlem Rep. Charles Rangel looks up at reporters while voting in New York, June 28, 2016. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig, File)

FILE - In this July 26, 1974 file photo, Reps. Charles Rangel, D-N.Y., and Barbara Jordan, D-Tex., left, look over a copy of the Constitution during a House Judiciary Committee debate on articles of impeachment for President Richard Nixon in Washington, D.C. (AP Photo/File)

FILE - Congressman Charles Rangel leaves a rally for airport workers at LaGuardia Airport in the Queens borough of New York, June 26, 2014. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig, File)

FILE - In this June 16, 2016 file photo, Rep. Charles Rangel, D-N.Y., speaks at a news conference on Capitol Hill in Washington. Rangel retires after more than four decades in office. (AP Photo/Lauren Victoria Burke, File)

NEW YORK (AP) — Reviving a campaign pledge, President Donald Trump wants a one-year, 10% cap on credit card interest rates, a move that could save Americans tens of billions of dollars but drew immediate opposition from an industry that has been in his corner.

Trump was not clear in his social media post Friday night whether a cap might take effect through executive action or legislation, though one Republican senator said he had spoken with the president and would work on a bill with his “full support.” Trump said he hoped it would be in place Jan. 20, one year after he took office.

Strong opposition is certain from Wall Street in addition to the credit card companies, which donated heavily to his 2024 campaign and have supported Trump's second-term agenda. Banks are making the argument that such a plan would most hurt poor people, at a time of economic concern, by curtailing or eliminating credit lines, driving them to high-cost alternatives like payday loans or pawnshops.

“We will no longer let the American Public be ripped off by Credit Card Companies that are charging Interest Rates of 20 to 30%,” Trump wrote on his Truth Social platform.

Researchers who studied Trump’s campaign pledge after it was first announced found that Americans would save roughly $100 billion in interest a year if credit card rates were capped at 10%. The same researchers found that while the credit card industry would take a major hit, it would still be profitable, although credit card rewards and other perks might be scaled back.

About 195 million people in the United States had credit cards in 2024 and were assessed $160 billion in interest charges, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau says. Americans are now carrying more credit card debt than ever, to the tune of about $1.23 trillion, according to figures from the New York Federal Reserve for the third quarter last year.

Further, Americans are paying, on average, between 19.65% and 21.5% in interest on credit cards according to the Federal Reserve and other industry tracking sources. That has come down in the past year as the central bank lowered benchmark rates, but is near the highs since federal regulators started tracking credit card rates in the mid-1990s. That’s significantly higher than a decade ago, when the average credit card interest rate was roughly 12%.

The Republican administration has proved particularly friendly until now to the credit card industry.

Capital One got little resistance from the White House when it finalized its purchase and merger with Discover Financial in early 2025, a deal that created the nation’s largest credit card company. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which is largely tasked with going after credit card companies for alleged wrongdoing, has been largely nonfunctional since Trump took office.

In a joint statement, the banking industry was opposed to Trump's proposal.

“If enacted, this cap would only drive consumers toward less regulated, more costly alternatives," the American Bankers Association and allied groups said.

Bank lobbyists have long argued that lowering interest rates on their credit card products would require the banks to lend less to high-risk borrowers. When Congress enacted a cap on the fee that stores pay large banks when customers use a debit card, banks responded by removing all rewards and perks from those cards. Debit card rewards only recently have trickled back into consumers' hands. For example, United Airlines now has a debit card that gives miles with purchases.

The U.S. already places interest rate caps on some financial products and for some demographics. The Military Lending Act makes it illegal to charge active-duty service members more than 36% for any financial product. The national regulator for credit unions has capped interest rates on credit union credit cards at 18%.

Credit card companies earn three streams of revenue from their products: fees charged to merchants, fees charged to customers and the interest charged on balances. The argument from some researchers and left-leaning policymakers is that the banks earn enough revenue from merchants to keep them profitable if interest rates were capped.

"A 10% credit card interest cap would save Americans $100 billion a year without causing massive account closures, as banks claim. That’s because the few large banks that dominate the credit card market are making absolutely massive profits on customers at all income levels," said Brian Shearer, director of competition and regulatory policy at the Vanderbilt Policy Accelerator, who wrote the research on the industry's impact of Trump's proposal last year.

There are some historic examples that interest rate caps do cut off the less creditworthy to financial products because banks are not able to price risk correctly. Arkansas has a strictly enforced interest rate cap of 17% and evidence points to the poor and less creditworthy being cut out of consumer credit markets in the state. Shearer's research showed that an interest rate cap of 10% would likely result in banks lending less to those with credit scores below 600.

The White House did not respond to questions about how the president seeks to cap the rate or whether he has spoken with credit card companies about the idea.

Sen. Roger Marshall, R-Kan., who said he talked with Trump on Friday night, said the effort is meant to “lower costs for American families and to reign in greedy credit card companies who have been ripping off hardworking Americans for too long."

Legislation in both the House and the Senate would do what Trump is seeking.

Sens. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., and Josh Hawley, R-Mo., released a plan in February that would immediately cap interest rates at 10% for five years, hoping to use Trump’s campaign promise to build momentum for their measure.

Hours before Trump's post, Sanders said that the president, rather than working to cap interest rates, had taken steps to deregulate big banks that allowed them to charge much higher credit card fees.

Reps. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., and Anna Paulina Luna, R-Fla., have proposed similar legislation. Ocasio-Cortez is a frequent political target of Trump, while Luna is a close ally of the president.

Seung Min Kim reported from West Palm Beach, Fla.

President Donald Trump arrives on Air Force One at Palm Beach International Airport, Friday, Jan. 9, 2025, in West Palm Beach, Fla. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

FILE - Visa and Mastercard credit cards are shown in Buffalo Grove, Ill., Feb. 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Nam Y. Huh, File)