The attorneys who shepherded the blockbuster antitrust lawsuit to fruition for hundreds of thousands of college athletes will share in just over $475 million in fees, and the figure could rise to more than $725 million over the next 10 years.

The request for plaintiff legal fees in the House vs. NCAA case, outlined in a December court filing and approved Friday night, struck experts in class-action litigation as reasonable.

Co-lead counsels Steve Berman and Jeffrey Kessler asked for $475.2 million, or 18.3% of the cash common funds of $2.596 billion.

They also asked for an additional $250 million, for a total of $725.2 million, based on a widely accepted estimate of an additional $20 billion in direct benefits to athletes over the 10-year settlement term. That would be 3.2% of what would then be a $22.596 billion settlement.

“Class Counsel have represented classes of student-athletes in multiple litigations challenging NCAA restraints on student-athlete compensation, and they have achieved extraordinary results. Class Counsel’s representation of the settlement class members here is no exception,” U.S. District Judge Claudia Wilken wrote.

University of Buffalo law professor Christine Bartholomew, who researched about 1,300 antitrust class-action settlements from 2005-22 for a book she authored, told The Associated Press the request for attorneys' fees could have been considered a bit low given the difficulty of the case, which dates back five years.

She said it is not uncommon for plaintiffs’ attorneys to be granted as much as 30% of the common funds.

Attorneys’ fees generally are calculated by multiplying an hourly rate by the number of hours spent working on a case. In class-action lawsuits, though, plaintiffs’ attorneys work on a contingency basis, meaning they get paid at the end of the case only if the class wins a financial settlement.

“Initially, you look at it and think this is a big number,” Bartholomew said. “When you look at how contingency litigation works generally, and then you think about how this fits into the class-action landscape, this is not a particularly unusual request.”

The original lawsuit was filed in June 2020 and it took until November 2023 for Wilken to grant class certification, meaning she thought the case had enough merit to proceed. Elon University law professor Catherine Dunham said gaining class certification is challenging in any case, but especially a complicated one like this.

“If a law firm takes on a case like this where you have thousands of plaintiffs and how many depositions and documents, what that means is the law firm can’t do other work while they’re working on the case and they are taking on the risk they won’t get paid,” Dunham said. “If the case doesn’t certify as a class, they won’t get paid.”

In the request for fees, the firm of Hagens Berman said it had dedicated 33,952 staff hours to the case through mid-December 2024. Berman, whose rate is $1,350 per hour, tallied 1,116.5 hours. Kessler, of Winston & Strawn, said he worked 1,624 hours on the case at a rate of $1,980 per hour.

The case was exhaustive. Hundreds of thousands of documents totaling millions of pages were produced by the defendants — the NCAA, ACC, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-12 and SEC — as part of the discovery process.

Berman and Kessler wrote the “plaintiffs had to litigate against six well-resourced defendants and their high-powered law firms who fought every battle tooth and nail. To fend off these efforts, counsel conducted extensive written discovery and depositions, and submitted voluminous expert submissions and lengthy briefing. In addition, class counsel also had to bear the risk of perpetual legislative efforts to kill these cases.”

Antitrust class-action cases are handled by the federal court system and have been harder to win since 2005, when the U.S. Class Action Fairness Act was passed, according to Bartholomew.

“Defendants bring motion after motion and there’s more of a pro-defendant viewpoint in federal court than there had been in state court,” she said. “As a result, you would not be surprised that courts, when cases do get through to fruition, are pretty supportive of applications for attorneys’ fees because there’s great risk that comes from bringing these cases fiscally for the firms who, if the case gets tossed early, never gets compensated for the work they’ve done.”

AP college sports: https://apnews.com/hub/college-sports

FILE - Attorney Jeffrey Kessler arrives at federal court on Monday, April 7, 2025, in Oakland, Calif. (AP Photo/Noah Berger, File)

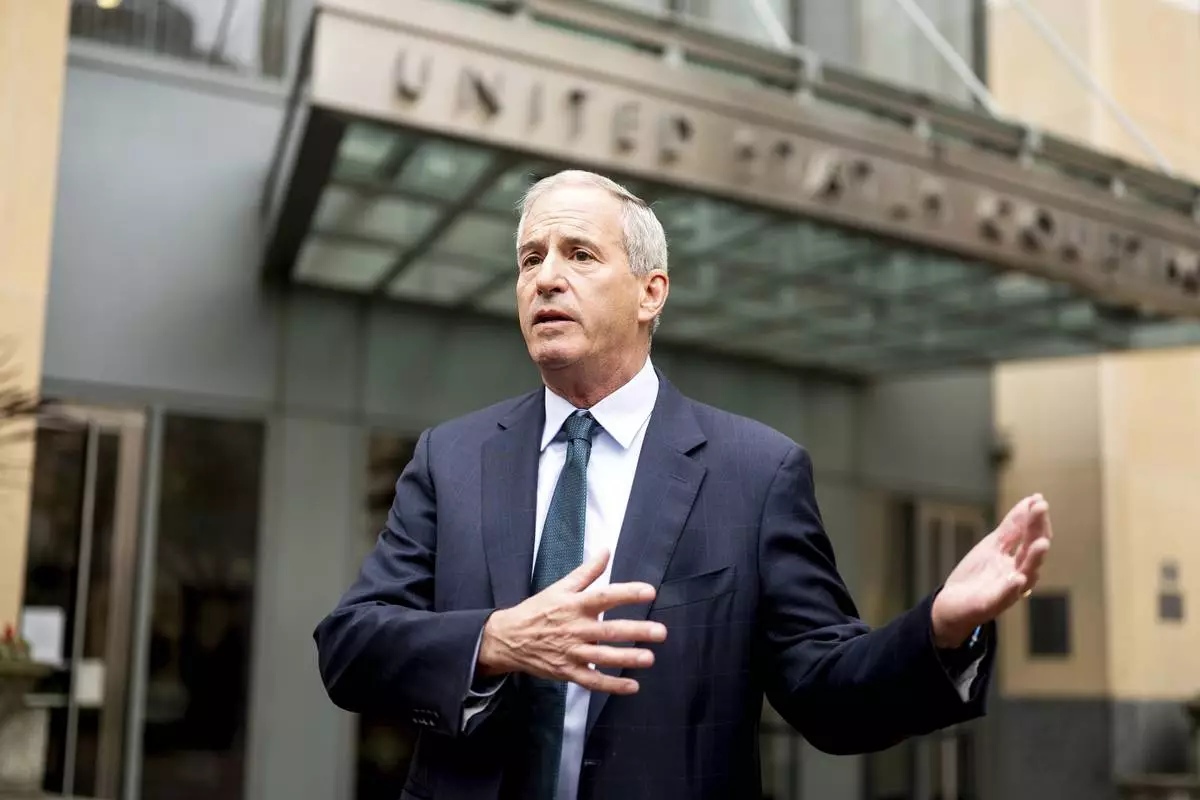

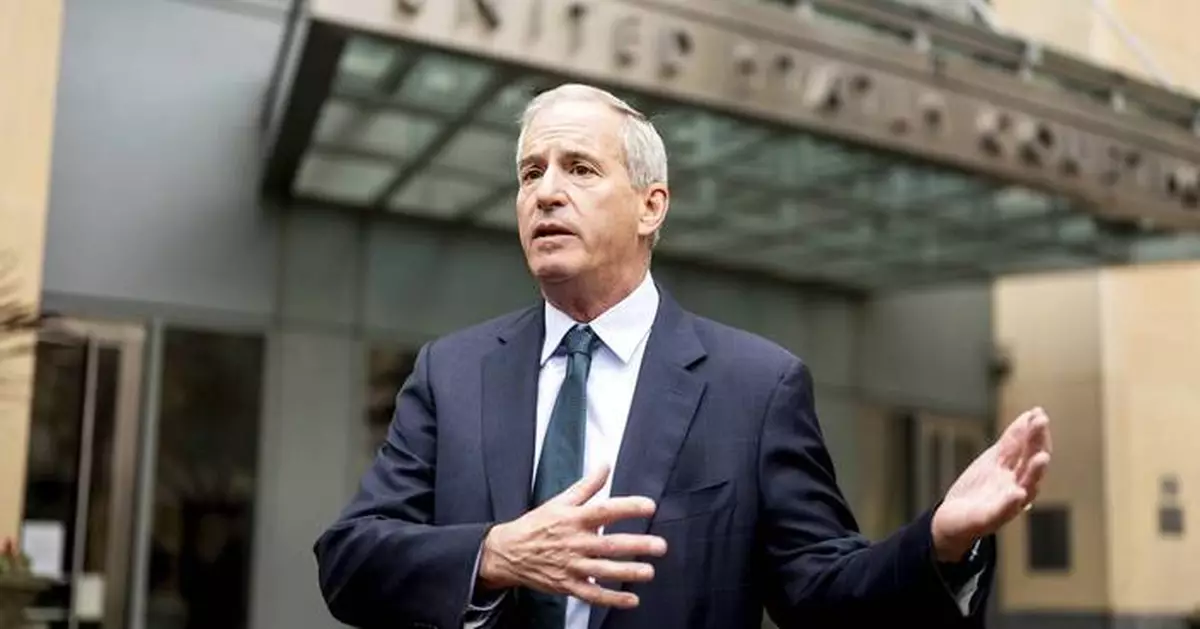

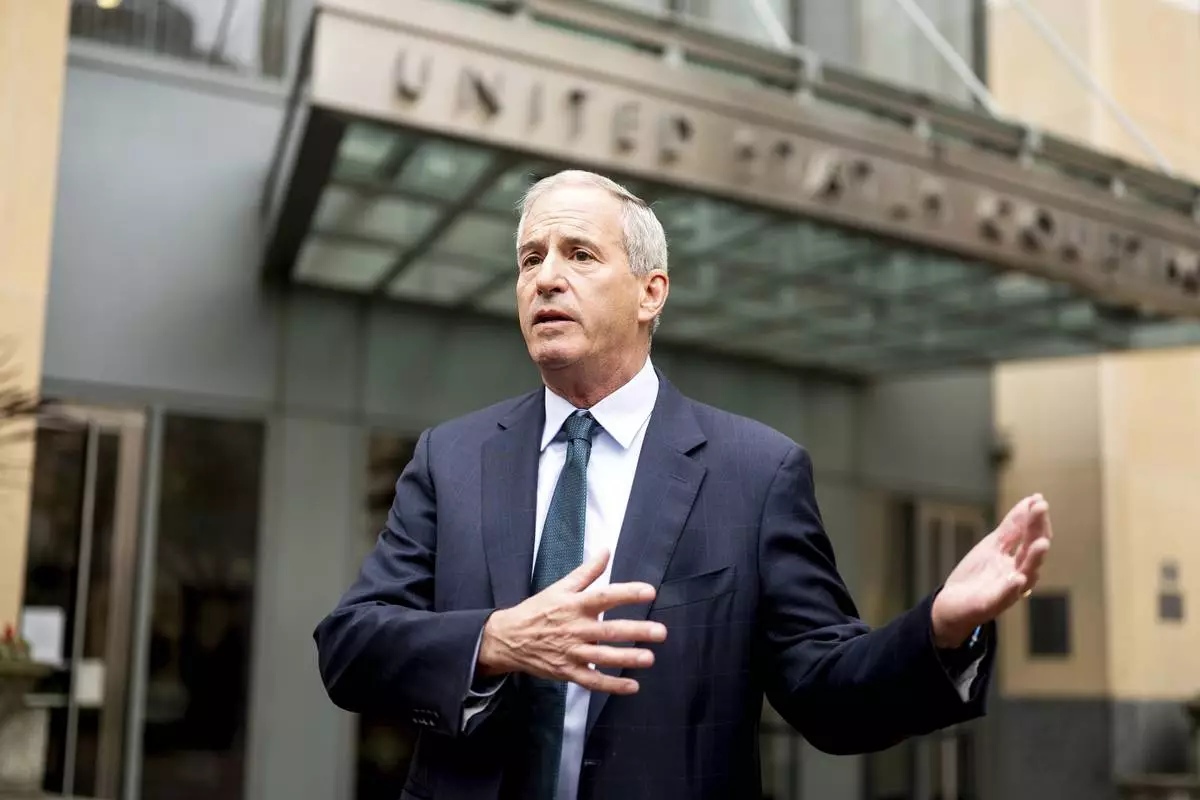

FILE - Attorney Steve Berman arrives at federal court on Monday, April 7, 2025, in Oakland, Calif. (AP Photo/Noah Berger, File)

BRUSSELS (AP) — European Union leaders stalled early Friday in talks to provide a massive loan to Ukraine using frozen Russian assets, officials said, as Belgium sought ironclad guarantees from its partners that they would protect the country from any retaliation by Russia.

The leaders want to use the Russian assets for a “reparation loan” to fund Ukraine's military and economic needs for the next two years. Kyiv would only pay back the money once Russia ends the war, now in its fourth year, and pays hundreds of billions for the destruction it has caused.

But the bulk of the assets — some 193 billion euros ($226 billion) as of September — are held in the Brussels-based financial clearing house Euroclear and Belgium wants to protect its interests. Russia’s Central Bank has launched a lawsuit against Euroclear and Belgium has doubts that the loan is legally sturdy.

“After lengthy discussions, it is clear that the reparations loans will require more work as leaders need more time to go through the details,” said an EU official, who was permitted to brief reporters on developments in the sensitive talks on condition that they not be named.

Talks on a plan B of raising the funds on international markets continued, even though there appeared to be no easy way to secure the unanimous support of all 27 member countries for it to pass.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy meanwhile pleaded for a quick decision to keep Ukraine afloat in the new year.

Belgium fears that Russia will strike back and prefers the plan B. It says frozen assets held in other European countries should be thrown into the pot as well, and that its partners should guarantee that Euroclear will have the funds it needs should it come under legal attack.

An estimated 25 billion euros ($29 billion) in Russian assets are frozen in banks and financial institutions in other EU countries, including France, Germany and Luxembourg.

“Give me a parachute and we’ll all jump together,” Belgian Prime Minister Bart De Wever told lawmakers ahead of the summit in reference to the reparation loan plan. “If we have confidence in the parachute that shouldn’t be a problem.”

The Russian Central Bank's lawsuit ramped up pressure on Belgium and its EU partners ahead of the summit.

The loan plan would see the EU lend 90 billion euros ($106 billion) to Ukraine. Countries like the United Kingdom, which said Thursday it is prepared to share the risk, as well as Canada and Norway would help make up any shortfall.

Russia's claim to the assets would still stand, but the assets would remain locked away at least until the Kremlin ends its war on Ukraine and pays for the massive damage it caused.

In mapping out the loan plan, the European Commission set up safeguards to protect Belgium, but De Wever has remained unconvinced.

Soon after arriving at EU headquarters Thursday morning, the Ukrainian president sat down with the Belgian prime minister to make his case for freeing up the frozen funds. The war-ravaged country is at risk of bankruptcy and needs new money by spring.

“Ukraine has the right to this money because Russia is destroying us, and to use these assets against these attacks is absolutely just,'' Zelenskyy told a news conference.

In an appeal to Belgian citizens who share their leader's worries about retaliation, Zelenskyy said: “One can fear certain legal steps in courts from the Russian Federation, but it’s not as scary as when Russia is at your borders.''

“So while Ukraine is defending Europe, you must help Ukraine,” he said.

Whatever method they use, the leaders have pledged to meet most of Ukraine's needs in 2026 and 2027. The International Monetary Fund estimates that would amount to 137 billion euros ($160 billion).

EU Council President António Costa, who is chairing the meeting, vowed to keep leaders negotiating until an agreement is reached, even if it takes days.

Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk said it was a case of sending "either money today or blood tomorrow" to help Ukraine.

German Chancellor Friedrich Merz said that he hopes Belgium's concerns can be addressed.

"The reactions of the Russian president in recent hours show how necessary this is. In my view, this is indeed the only option. We are basically faced with the choice of using European debt or Russian assets for Ukraine, and my opinion is clear: We must use the Russian assets.”

Hungary and Slovakia oppose a reparations loan. Apart from Belgium, Bulgaria, Italy and Malta are also undecided, but as many as nine countries might be required to block the move.

“I would not like a European Union in war," said Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, who sees himself as a peacemaker. He’s also Russian President Vladimir Putin’s closest ally in Europe. “To give money means war.”

Orbán described the loan plan as a “dead end.''

The outcome of the summit has significant ramifications for Europe's place in negotiations to end the war. The United States wants assurances that the Europeans are intent on supporting Ukraine financially and backing it militarily — even as negotiations to end the war drag on without substantial results.

The loan plan poses important challenges to the way the bloc goes about its business. Should a two-thirds majority of EU leaders decide to impose the scheme on Belgium, which has most to lose, the impact on decision-making in Europe would be profound.

The EU depends on consensus, and finding voting majorities and avoiding vetoes in the future could become infinitely more complex if one of the EU's founding members is forced to weather an attack on its interests by its very own partners.

De Wever too must weigh whether the cost of holding out against a majority is worth the hit his government's credibility would take in Europe.

Associated Press writers Kirsten Grieshaber in Berlin and Illia Novikov in Kyiv, Ukraine, contributed to this report.

From left, Portugal's Prime Minister Luis Montenegro, European Council President Antonio Costa, French President Emmanuel Macron and Hungary's Prime Minister Viktor Orban during a round table meeting at the EU Summit in Brussels, Thursday, Dec. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Geert Vanden Wijngaert)

European Council President Antonio Costa, center right, speaks with Denmark's Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen, center left, during a round table meeting at the EU Summit in Brussels, Thursday, Dec. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Geert Vanden Wijngaert)

Belgium's Prime Minister Bart De Wever, center, speaks with from left, Cypriot President Nikos Christodoulides, Netherland's Prime Minister Dick Schoof, Luxembourg's Prime Minister Luc Frieden and Poland's Prime Minister Donald Tusk during a round table meeting at the EU Summit in Brussels, Thursday, Dec. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Geert Vanden Wijngaert)

Hungary's Prime Minister Viktor Orban speaks with the media as he arrives for the EU Summit in Brussels, Thursday, Dec. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Geert Vanden Wijngaert)

Hungary's Prime Minister Viktor Orban, right, arrives for the EU Summit in Brussels, Thursday, Dec. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Omar Havana)

Italy's Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, center, is greeted as she arrives for a round table meeting on migration at the EU Summit in Brussels, Thursday, Dec. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Olivier Hoslet, Pool Photo via AP)

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, right, and Germany's Chancellor Friedrich Merz, left, attend a round table meeting on migration at the EU Summit in Brussels, Thursday, Dec. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Olivier Hoslet, Pool Photo via AP)

FILE - A view of the headquarters of Euroclear in Brussels, on Oct. 23, 2025. (AP Photo/Geert Vanden Wijngaert, File)