Randy Hopkins, a consultant to the Portland State University History Department, says the Japanese government was behind a smear campaign against Iris Chang, the late Chinese-American writer who exposed horrific details about the Nanjing Massacre perpetrated by Japanese soldiers in the 1930s.

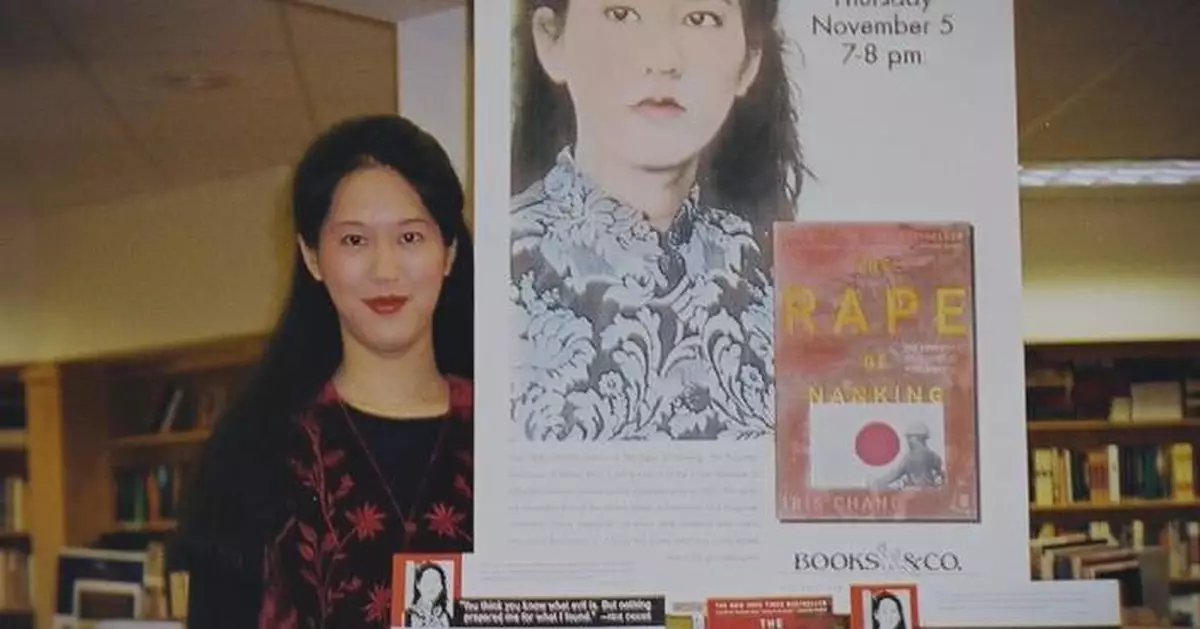

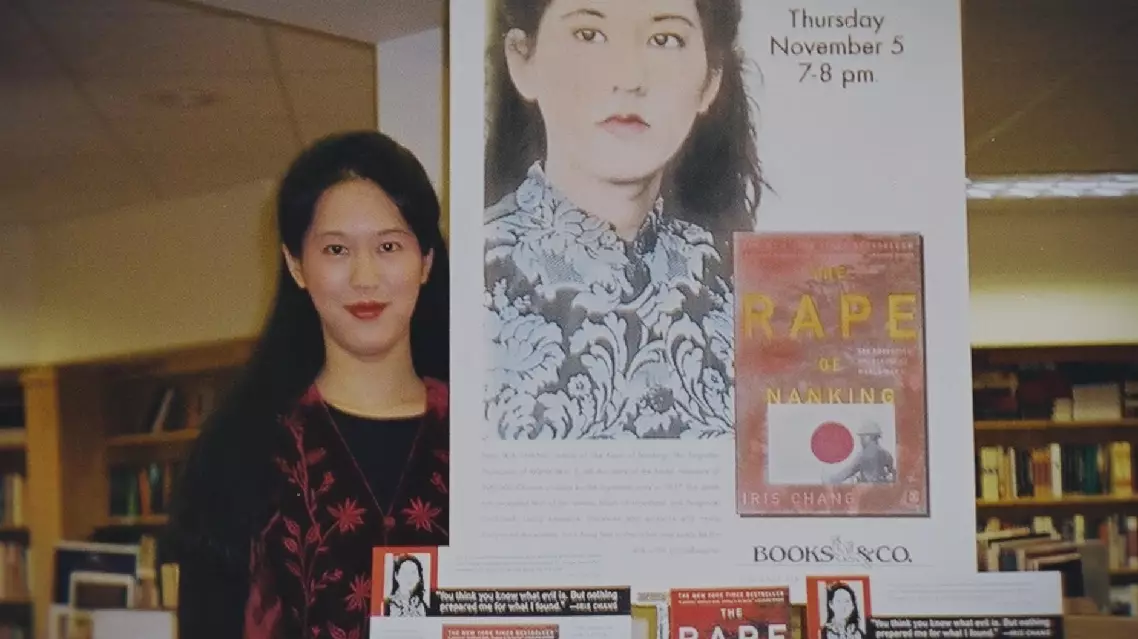

Chang, whose Chinese name was Zhang Chunru, was the author of "The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II," a best-selling book published in 1997.

The massacre, which lasted for more than 40 days following Japanese troops' capture of Nanjing, the then Chinese capital, on Dec. 13, 1937, left more than 300,000 Chinese civilians and unarmed soldiers in Nanjing dead and 20,000 women raped.

In December 1998, Chang confronted the then Japanese ambassador to the U.S. Kunihiko Saito on American television, challenging him to apologize for the horrors. He would only respond that Japan did recognize that really unfortunate things happened, and acts of violence were committed by members of the Japanese military.

"We saw that Iris performed very well. She was very tough. Because he was then Japanese ambassador to the United States, we were naturally very worried. The following day, when my husband visited the physics department where he taught, a friend of him advised, 'If I were you, I would get a bodyguard for your daughter.' This made me even more worried," said Chang’s mother Zhang Yingying.

"After her book became a New York Times bestseller, the right-wing forces in Japan who wanted to cover up that part of history started to attack her. Their articles criticizing her kept appearing in Japanese newspapers using all kinds of methods. One of her most vocal critics is Joshua Fogel. He specifically targeted her work, claiming that her use of the word 'holocaust' in the title was inappropriate because, in his view, 'holocaust' exclusively refers to the massacre of Jews during World War II and should not be applied to describe massacre in China. In fact, if you look it up in the dictionary, 'holocaust' is not a word exclusive to Jews," she explained.

Hopkins, who co-authored a book with Chang’s mother called "Iris Chang and The Power of One," said that Japanese publications like Japan Echo, supported by the Japanese government, had engaged in a malicious defamation campaign against Chang.

"It was a monthly periodical that published in English and was distributed to the English-speaking world to give people a favorable idea about Japan. And included in those publications were a series of anti-Iris Chang articles. In 2007, on the 70th anniversary of the Nanjing Massacre, they were published in book form. When the Japanese Foreign Ministry cut off the funding to the publishers of the book, they outed the truth on their website. Basically, they said 'we've been sponsored by the Japanese Foreign Ministry and now that they're not sponsoring us, Japan Echo is going to fold.' So that's how I found out about the Japanese Foreign Ministry's involvement," said Hopkins.

"She once received a threatening letter, with two bullets inside. I was just stunned. She didn't tell me much either," Zhang added.

At the age of 36, suffering from depression, Chang took her own life.

"And every time those anniversaries come around, the world's attention is going to be refocused on what happened. And I want our book there when those time periods come around, so that Iris' version is told and told again. She showed the power of one person to dig into the evidence and to reveal truth, and I find that it immensely admirable," said Hopkins.

"If we fail to preserve the memory of this history, it will repeat itself in the future. That is why the Japanese do not want us to remember it. They downplay it and cover it up. But as the victims, we must remember and pass it on from generation to generation," said Zhang.

US scholar says Japanese government behind defamation of "Rape of Nanking" author