BISMARCK, N.D. (AP) — Air traffic controllers at a small North Dakota airport didn't inform an Air Force bomber's crew that a commercial airliner was flying in the same area, the military said, shedding light on the nation's latest air safety scare.

A SkyWest pilot performed a sharp turn, startling passengers, to avoid colliding with the B-52 bomber he said was in his flight path as he prepared to land Friday at Minot International Airport.

The bomber had been conducting a flyover at the North Dakota State Fair in Minot approved in consultation with the Federal Aviation Administration, the Minot International Airport air traffic control and the Minot Air Force Base's air traffic control team, the Air Force said in a statement Monday.

As the bomber headed to the fairgrounds shortly before 8 p.m., the base's air traffic control advised its crew to contact the Minot airport's air traffic control.

“The B-52 crew contacted Minot International Airport tower and the tower provided instructions to continue 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) westbound after the flyover,” the Air Force said. “The tower did not advise of the inbound commercial aircraft.”

Video taken by a passenger on Delta Flight 3788 — which departed from Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport — captured audio of the SkyWest pilot explaining over the plane's intercom that he made the hard bank after spotting the bomber in the flight path that Minot air traffic control had directed him to take for landing.

“Sorry about the aggressive maneuver. It caught me by surprise,” the pilot can be heard saying on the video posted on social media. “This is not normal at all. I don’t know why they didn’t give us a heads up.”

The FAA, Air Force and SkyWest are investigating. The airliner had 76 passengers and four crew members onboard, SkyWest Airlines said.

It's just the latest flight scare in recent months. In February, a Southwest Airlines flight about to land at Chicago’s Midway Airport was forced to climb back into the sky to avoid another aircraft crossing the runway. That followed the tragic midair collision of a passenger jet and an Army helicopter over Washington, D.C., in January that killed all 67 people aboard the two aircraft. Those and other recent incidents have raised questions about the FAA's oversight.

And this incident renews questions raised after the Washington D.C. crash about how well the military communicates with civilian air traffic controllers when their flights are sharing the same airspace.

The FAA said Monday that a private company services the Minot air traffic control tower, and that the controllers there aren't FAA employees. It is one of 265 airport towers nationwide that are operated by companies, but the roughly 1,400 air traffic controllers at these smaller airports meet the same qualification and training requirements as FAA controllers at larger airports, the agency said.

The city of Minot, which owns and operates the airport, didn’t comment Tuesday on the Air Force’s statement, but said the airport is relying on the different agencies to conduct their investigations.

Phone and email messages left Tuesday for Midwest Air Traffic Control Inc., which provides air traffic control service for the Minot airport, were not immediately returned.

The contract tower program has been in place since 1982, and it has been repeatedly praised in reports from the Transportation Department's Inspector General.

Some small airports like Minot’s also don’t have their own radar systems on site. In fact, the vast majority of the nation’s airports don’t even have towers, mainly because most small airports don’t have passenger air service. But regional FAA radar facilities do oversee traffic all across the country, and an approach control radar center in Minneapolis helps direct planes in and out of Minot before controllers at the airport take over once they see the planes. The Minot airport typically handles between 18 and 24 flights a day.

Former NTSB and FAA crash investigator Jeff Guzzetti said it is common for small airports like Minot to operate without their own radars. He said radars are cost-prohibitive to install at every airport, and it generally works fine for airport controllers to direct planes into landing visually. If the weather is bad, a regional FAA radar facility may be able to help, but ultimately planes simply won't be cleared to land if the weather is too bad.

Guzzetti who oversaw one of the Inspector General reports, said the contract tower program has been hugely successful and improves safety at small airports because if they didn't have a contract tower, small airports would be uncontrolled. And he said the safety record of contract towers is similar — if not better — than federal towers.

“We still have to see what happened here. But even if it was a controller screwup, I don’t think that should indict or raise questions about the contract tower program. It’s been a stalwart,” Guzzetti said.

Funk reported from Omaha, Nebraska. Associated Press writer Margery A. Beck contributed from Omaha.

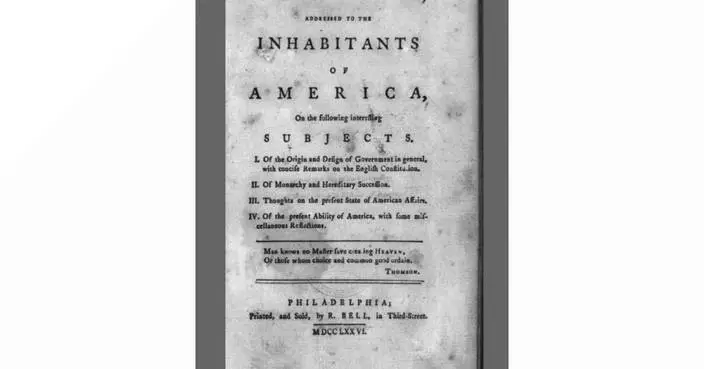

This photo from the North Dakota Governor's Office shows a B-52 bomber from Minot Air Force Base in a flyover at the North Dakota State Fair on Friday, July 18, 2025, in Minot, N.D.. (North Dakota Governor's Office via AP)

NEW YORK (AP) — Reviving a campaign pledge, President Donald Trump wants a one-year, 10% cap on credit card interest rates, a move that could save Americans tens of billions of dollars but drew immediate opposition from an industry that has been in his corner.

Trump was not clear in his social media post Friday night whether a cap might take effect through executive action or legislation, though one Republican senator said he had spoken with the president and would work on a bill with his “full support.” Trump said he hoped it would be in place Jan. 20, one year after he took office.

Strong opposition is certain from Wall Street in addition to the credit card companies, which donated heavily to his 2024 campaign and have supported Trump's second-term agenda. Banks are making the argument that such a plan would most hurt poor people, at a time of economic concern, by curtailing or eliminating credit lines, driving them to high-cost alternatives like payday loans or pawnshops.

“We will no longer let the American Public be ripped off by Credit Card Companies that are charging Interest Rates of 20 to 30%,” Trump wrote on his Truth Social platform.

Researchers who studied Trump’s campaign pledge after it was first announced found that Americans would save roughly $100 billion in interest a year if credit card rates were capped at 10%. The same researchers found that while the credit card industry would take a major hit, it would still be profitable, although credit card rewards and other perks might be scaled back.

About 195 million people in the United States had credit cards in 2024 and were assessed $160 billion in interest charges, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau says. Americans are now carrying more credit card debt than ever, to the tune of about $1.23 trillion, according to figures from the New York Federal Reserve for the third quarter last year.

Further, Americans are paying, on average, between 19.65% and 21.5% in interest on credit cards according to the Federal Reserve and other industry tracking sources. That has come down in the past year as the central bank lowered benchmark rates, but is near the highs since federal regulators started tracking credit card rates in the mid-1990s. That’s significantly higher than a decade ago, when the average credit card interest rate was roughly 12%.

The Republican administration has proved particularly friendly until now to the credit card industry.

Capital One got little resistance from the White House when it finalized its purchase and merger with Discover Financial in early 2025, a deal that created the nation’s largest credit card company. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which is largely tasked with going after credit card companies for alleged wrongdoing, has been largely nonfunctional since Trump took office.

In a joint statement, the banking industry was opposed to Trump's proposal.

“If enacted, this cap would only drive consumers toward less regulated, more costly alternatives," the American Bankers Association and allied groups said.

Bank lobbyists have long argued that lowering interest rates on their credit card products would require the banks to lend less to high-risk borrowers. When Congress enacted a cap on the fee that stores pay large banks when customers use a debit card, banks responded by removing all rewards and perks from those cards. Debit card rewards only recently have trickled back into consumers' hands. For example, United Airlines now has a debit card that gives miles with purchases.

The U.S. already places interest rate caps on some financial products and for some demographics. The Military Lending Act makes it illegal to charge active-duty service members more than 36% for any financial product. The national regulator for credit unions has capped interest rates on credit union credit cards at 18%.

Credit card companies earn three streams of revenue from their products: fees charged to merchants, fees charged to customers and the interest charged on balances. The argument from some researchers and left-leaning policymakers is that the banks earn enough revenue from merchants to keep them profitable if interest rates were capped.

"A 10% credit card interest cap would save Americans $100 billion a year without causing massive account closures, as banks claim. That’s because the few large banks that dominate the credit card market are making absolutely massive profits on customers at all income levels," said Brian Shearer, director of competition and regulatory policy at the Vanderbilt Policy Accelerator, who wrote the research on the industry's impact of Trump's proposal last year.

There are some historic examples that interest rate caps do cut off the less creditworthy to financial products because banks are not able to price risk correctly. Arkansas has a strictly enforced interest rate cap of 17% and evidence points to the poor and less creditworthy being cut out of consumer credit markets in the state. Shearer's research showed that an interest rate cap of 10% would likely result in banks lending less to those with credit scores below 600.

The White House did not respond to questions about how the president seeks to cap the rate or whether he has spoken with credit card companies about the idea.

Sen. Roger Marshall, R-Kan., who said he talked with Trump on Friday night, said the effort is meant to “lower costs for American families and to reign in greedy credit card companies who have been ripping off hardworking Americans for too long."

Legislation in both the House and the Senate would do what Trump is seeking.

Sens. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., and Josh Hawley, R-Mo., released a plan in February that would immediately cap interest rates at 10% for five years, hoping to use Trump’s campaign promise to build momentum for their measure.

Hours before Trump's post, Sanders said that the president, rather than working to cap interest rates, had taken steps to deregulate big banks that allowed them to charge much higher credit card fees.

Reps. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., and Anna Paulina Luna, R-Fla., have proposed similar legislation. Ocasio-Cortez is a frequent political target of Trump, while Luna is a close ally of the president.

Seung Min Kim reported from West Palm Beach, Fla.

President Donald Trump arrives on Air Force One at Palm Beach International Airport, Friday, Jan. 9, 2025, in West Palm Beach, Fla. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

FILE - Visa and Mastercard credit cards are shown in Buffalo Grove, Ill., Feb. 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Nam Y. Huh, File)