EAST PROVIDENCE, R.I. (AP) — Every time he rushed out on a fire call, East Providence Lt. Thomas Votta knew he put himself at risk for cancer. There are potential carcinogens in the smoke billowing out of a house fire, but also risks from wearing his chemically-treated gear.

Last month, the Rhode Island fire department became the nation's first to give the 11-year veteran and all his 124 fellow firefighters new gear free of PFAS, or perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

Click to Gallery

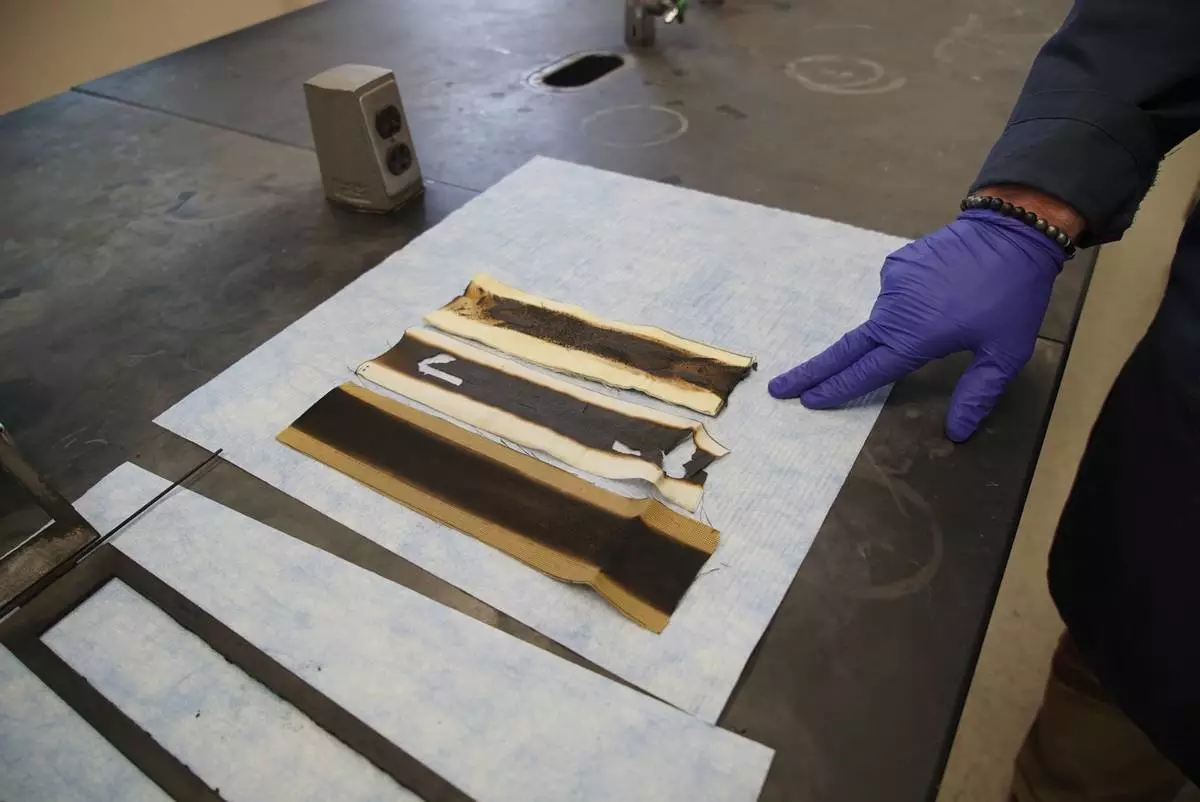

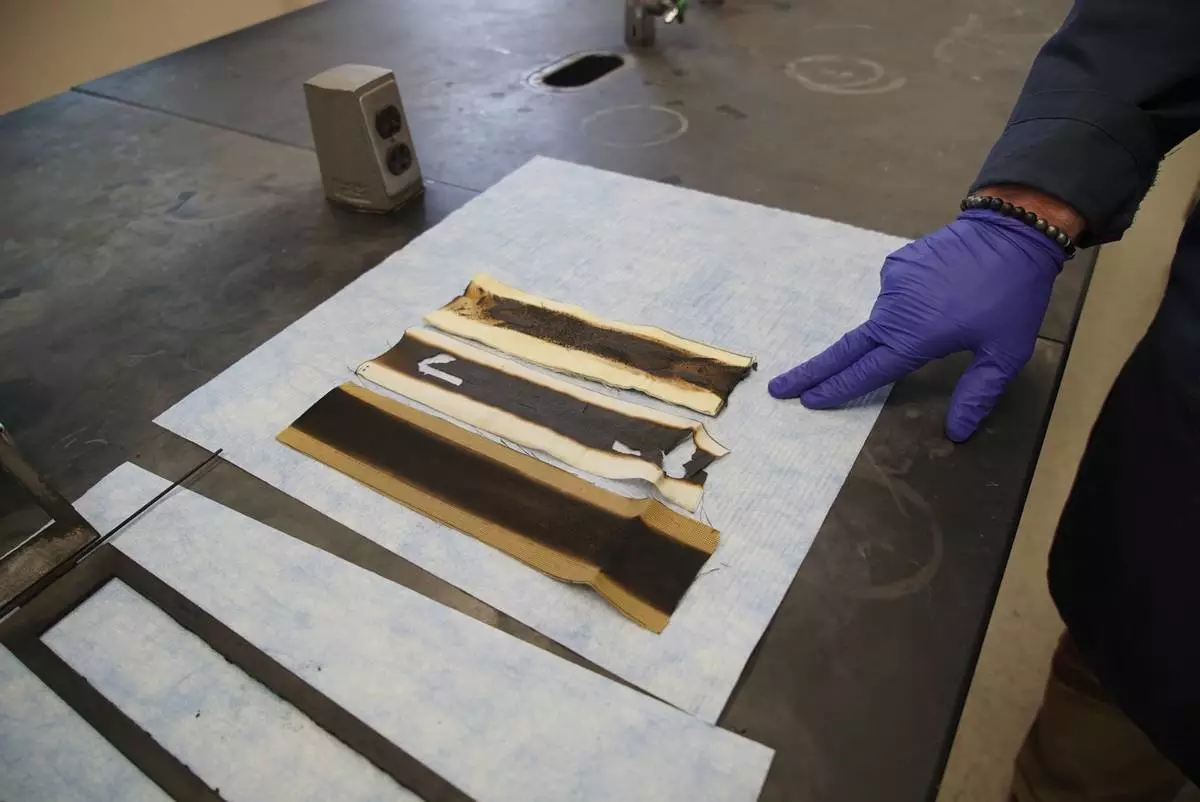

Charred pieces of non-PFAS-treated fabric sit on a lab bench following a burn test at North Carolina State University's Wilson College of Textiles in Raleigh, N.C., Aug. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Allen G. Breed)

Bryan Ormond, a professor at the Textile Protection and Comfort Center at North Carolina State University, talks about the protective layers in a firefighter jacket on Aug. 8, 2025, in Raleigh, N.C. (AP Photo/Allen G. Breed)

Firefighters respond to a fire while wearing recently issued non-PFAS turnout gear on July 3, 2025, in East Providence, R.I. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Firefighter Christopher Harrington stands next to the station's old turnout gear, while wearing recently issued non-PFAS turnout gear, at Fire Station 4 on July 3, 2025, in East Providence, R.I. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Firefighter Brendan Dyer suits up in recently issued non-PFAS turnout gear at Fire Station 4 in East Providence, R.I., on July 3, 2025. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Known as forever chemicals because of how long they remain in the environment, PFAS have been linked to a host of health problems, including increased risk of certain cancers, cardiovascular disease and babies born with low birth weights.

“We are exposed to so many chemicals when we go to fires,” Votta said. “Having it inside our gear, touching or very close to our skin was very, very concerning. Knowing that’s gone now, it gives us a little bit of relief. We’re not getting it from every angle.”

The PFAS in the multilayered coats and pants — primarily meant to repel water and contaminants like oil and prevent moisture-related burns — have been a growing concern among firefighters for several years.

Cancer has replaced heart disease as the biggest cause of line-of-duty deaths, according to the International Association of Fire Fighters, the union that represents firefighters and EMS workers. Firefighters are at higher risk than the general population of getting skin, kidney and other types of cancer, according to a study led by the American Cancer Society.

Firefighters are exposed to smoke from faster and hotter blazes in buildings and wildfires, many containing toxic chemicals like arsenic and asbestos. In addition to the PFAS in their gear, the IAFF is also concerned about firefighting foam that contains the chemical and is being phased out in many places.

“The question that is obvious to us is that why would we have carcinogens intentionally infused into our personal protective equipment?” IAFF General President Edward Kelly, who was elected in 2021 in part on a campaign to address PFAS dangers, said at a news conference this month.

It can be difficult to determine the cause of a firefighter's cancer since the disease can take years to develop and genetics, diet and other lifestyle factors can play a role, experts say. Where a firefighter works — cities, suburbs or rural areas — also can impact the level of exposure to toxins.

“That’s good they’re shining a light on the health of their workers,” said Dr. Lecia Sequist, program director at the Cancer Early Detection and Diagnostics Clinic at Mass General Hospital.

“But I don’t think the data is mature enough that we have a clear understanding of what the unique causes of cancer in firefighters might be that’s different from the general population.”

Still, health concerns among firefighters have sparked a flurry of lawsuits against makers of gear and PFAS chemicals. Seven states, including Massachusetts and Rhode Island, have passed laws banning PFAS in gear and two others introduced bills calling for bans, according to the IAFF.

The union has also targeted the agency that sets voluntary standards for firefighting gear and other safety requirements. In a 2023 lawsuit, the union accused the National Fire Protection Association, or NFPA, of setting standards that can only be met with PFAS-treated material and working with several gear makers to maintain that requirement — something the association denied.

Last year, the agency announced new standards restricting use of 24 classes of chemicals including PFAS in gear — though it is considering delaying the law until March to give companies more time to comply.

“The development of this new standard marks the most significant and complex shift in how firefighter protective gear is made in a generation," said NFPA spokesperson Tom Lyons.

Amid the state bans and legal fights, some of the largest gear makers are shifting away from PFAS. Smaller companies have also emerged marketing what they claim is PFAS-free gear. Hydrocarbon wax or silicone-based finish often replaces PFAS in the outer shell and removes it from the middle, moisture barrier.

The changing gear landscape is giving fire departments an opportunity to make the switch to safer alternatives.

Vancouver, Canada, purchased PFAS-free gear last year while Manchester, New Hampshire, bought new gear in March. Gilroy, California, and Belmont, Massachusetts, are in the process of making the switch, the IAFF said.

“We’re trying to take every step possible to limit their exposure to the chemicals," said Manchester Assistant Chief Matt Lamothe.

But switching to PFAS alternatives hasn't been easy.

Since companies often don't list chemicals in gear, fire departments are often in the dark as to whether it's actually safer while also complying with heat stress, moisture and durability requirements. And PFAS-treated gear is still on the market, supported by the American Chemical Council, which argues these materials are the “only viable options” to “meet vital performance properties.”

San Francisco was considering getting PFAS-free gear from one company until tests showed the chemical was present. The company addressed the problem and the fire department bought its first 50 of 700 sets this month.

“The biggest challenge has been trust — or more accurately, the lack of it,” said Matthew Alba, a San Francisco department battalion chief who is being treated for a brain tumor he blames on fighting wildfires.

In Quincy, Massachusetts, the department bought what it thought were 30 sets of PFAS-free gear, but independent tests revealed the chemical's presence.

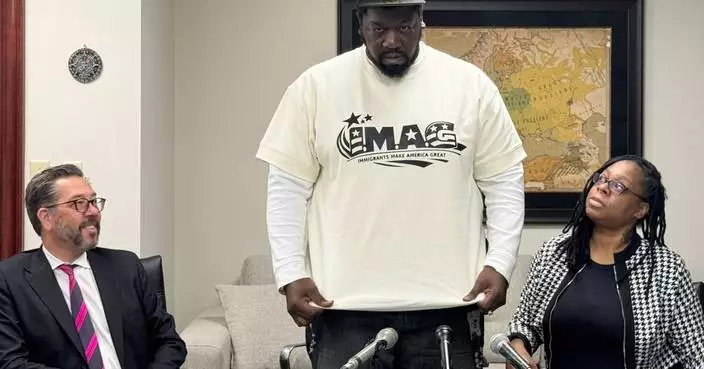

“These last few months dealing with this issue has been frustrating, angry and truthfully sad seeing what these companies continue to pull,” Tom Bowes, president of the IAFF local, told a news conference attended by dozens of Quincy firefighters this month.

Researchers at Duke and North Carolina State universities argue concerns over the new gear suggest the transition away from PFAS has been rushed — potentially exposing firefighters to new chemicals and giving them gear that hasn't been proven safe.

“I’ve talked to fire chiefs, fire departments across the country, across the world, they’re all dealing with it,” said Bryan Ormond, a professor at North Carolina State and director of its Milliken Textile Protection and Comfort Center. “They’re all trying to figure out ... how to move forward safely and protect our people because we don’t necessarily know what the new gear is going to do."

But Graham Peaslee, an emeritus professor at the University of Notre Dame who tested gear for San Francisco and Quincy and is working with five other departments, said concerns about PFAS-free gear were a “scare tactic” from the chemical companies that want to keep selling their products.

In East Providence, testing showed the fire department's first attempt to buy PFAS-free gear contained flame retardants that pose increased cancer risk and didn't adequately protect from heat. A new supplier provided PFAS-free materials that offered the heat protection.

“It's a home run,” Fire Chief Michael Carey said of the gear, which cost $658,000 and was paid for by pandemic funds.

“It takes a sizable weight off of my shoulders,” he said. “I don’t have to worry about them being in that gear and being exposed to a known carcinogen.”

Charred pieces of non-PFAS-treated fabric sit on a lab bench following a burn test at North Carolina State University's Wilson College of Textiles in Raleigh, N.C., Aug. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Allen G. Breed)

Bryan Ormond, a professor at the Textile Protection and Comfort Center at North Carolina State University, talks about the protective layers in a firefighter jacket on Aug. 8, 2025, in Raleigh, N.C. (AP Photo/Allen G. Breed)

Firefighters respond to a fire while wearing recently issued non-PFAS turnout gear on July 3, 2025, in East Providence, R.I. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Firefighter Christopher Harrington stands next to the station's old turnout gear, while wearing recently issued non-PFAS turnout gear, at Fire Station 4 on July 3, 2025, in East Providence, R.I. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Firefighter Brendan Dyer suits up in recently issued non-PFAS turnout gear at Fire Station 4 in East Providence, R.I., on July 3, 2025. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

WASHINGTON (AP) — When President Donald Trump announced the audacious capture of Nicolás Maduro to face drug trafficking charges in the U.S., he portrayed the strongman’s vice president and longtime aide as America’s preferred partner to stabilize Venezuela amid a scourge of drugs, corruption and economic mayhem.

Left unspoken was the cloud of suspicion that long surrounded Delcy Rodríguez before she became acting president of the beleaguered nation earlier this month.

In fact, Rodríguez has been on the radar of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration for years and in 2022 was even labeled a “priority target,” a designation DEA reserves for suspects believed to have a “significant impact” on the drug trade, according to records obtained by The Associated Press and more than a half dozen current and former U.S. law enforcement officials.

The DEA has amassed a detailed intelligence file on Rodríguez dating to at least 2018, the records show, cataloging her known associates and allegations ranging from drug trafficking to gold smuggling. One confidential informant told the DEA in early 2021 that Rodríguez was using hotels in the Caribbean resort of Isla Margarita “as a front to launder money,” the records show. As recently as last year she was linked to Maduro’s alleged bag man, Alex Saab, whom U.S. authorities arrested in 2020 on money laundering charges.

The U.S. government has never publicly accused Rodríguez of any criminal wrongdoing. Notably for Maduro’s inner circle, she’s not among the more than a dozen current Venezuelan officials charged with drug trafficking alongside the ousted president.

Rodríguez’s name has surfaced in nearly a dozen DEA investigations, several of which remain ongoing, involving agents in field offices from Paraguay and Ecuador to Phoenix and New York, the AP learned. The AP could not determine the specific focus of each investigation.

Three current and former DEA agents who reviewed the records at the request of AP said they indicate an intense interest in Rodríguez throughout much of her tenure as vice president, which began in 2018. They were not authorized to discuss DEA investigations and spoke on the condition of anonymity.

The records reviewed by AP do not make clear why Rodríguez was elevated to a “priority target,” a designation that requires extensive documentation to justify additional investigative resources. The agency has hundreds of priority targets at any given moment, and having the label does not necessarily lead to being charged criminally.

“She was on the rise, so it’s not surprising that she might become a high-priority target with her role,” said Kurt Lunkenheimer, a former federal prosecutor in Miami who has handled multiple cases related to Venezuela. “The issue is when people talk about you and you become a high-priority target, there’s a difference between that and evidence supporting an indictment.”

Venezuela's communications ministry did not respond to emails seeking comment.

The DEA and U.S. Justice Department also did not respond to requests for comment. Asked whether the president trusts Rodríguez, the White House referred AP to Trump’s earlier remarks on a “very good talk” he had with the acting president Wednesday, one day before she met in Caracas with CIA Director John Ratcliffe.

Almost immediately after Maduro’s capture, Trump started heaping praise on Rodríguez — this past week referring to her as a "terrific person — in close contact with officials in Washington, including Secretary of State Marco Rubio.

The DEA’s interest in Rodríguez comes even as Trump has sought to install her as the steward of American interests to navigate a volatile post-Maduro Venezuela, said Steve Dudley, co-director of InSight Crime, a think tank focused on organized crime in the Americas.

“The current Venezuela government is a criminal-hybrid regime. The only way you reach a position of power in the regime is by, at the very least, abetting criminal activities,” said Dudley, who has investigated Venezuela for years. “This isn’t a bug in the system. This is the system.”

Those sentiments were echoed by opposition leader María Corina Machado, who met with Trump at the White House Thursday in a bid to push for more U.S. support for Venezuelan democracy.

“The American justice system has sufficient information about her,” said Machado, referring to Rodríguez. “Her profile is quite clear.”

Rodríguez, 56, worked her way to the apex of power in Venezuela as a loyal aide to Maduro, with whom she shares a deep-seated leftist bent stemming from her socialist father’s death in police custody when she was only 7 years old. Despite blaming the U.S. for her father’s death, she steadily worked while foreign minister and later vice president to court American investment during the first Trump administration, hiring lobbyists close to Trump and even ordering the state oil company to make a $500,000 donation to his inaugural committee.

The charm offensive flopped when Trump, urged on by Rubio, pressured Maduro to hold free and fair elections. In September 2018,the White House sanctioned Rodríguez, describing her as key to Maduro’s grip on power and ability to “solidify his authoritarian rule.” She was also sanctioned earlier by the European Union.

But those allegations focused on her threat to Venezuela’s democracy, not any alleged involvement in corruption.

“Venezuela is a failed state that supports terrorism, corruption, human rights abuses and drug trafficking at the highest echelons. There is nothing political about this analysis,” said Rob Zachariasiewicz, a longtime former DEA agent who led investigations into top Venezuelan officials and is now a managing partner at Elicius Intelligence, a specialist investigations firm. “Delcy Rodríguez has been part of this criminal enterprise.”

The DEA records seen by AP provide an unprecedented glimpse into the agency’s interest in Rodríguez. Much of it was driven by the agency’s elite Special Operations Division, the same Virginia-based unit that worked with prosecutors in Manhattan to indict Maduro.

One of the records cites an unnamed confidential informant linking Rodríguez to hotels in Margarita Island that are allegedly used as a front to launder money. The AP has been unable to independently confirm the information.

The U.S. has long considered the resort island, northeast of the Venezuelan mainland, a strategic hub for drug trafficking routes to the Caribbean and Europe. Numerous traffickers have been arrested or taken haven there over the years, including representatives of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán’s Sinaloa cartel.

The records also indicate the feds were looking at Rodríguez’s involvement in government contracts awarded to Maduro’s ally Saab — investigations that remain ongoing even after President Joe Biden pardoned him in 2023 as part of a prisoner swap for Americans imprisoned in Venezuela.

The Colombian businessman rose to become one of Venezuela’s top fixers as U.S. sanctions cut off its access to hard currency and Western banks. He was arrested in 2020 on federal charges of money laundering while traveling from Venezuela to Iran to negotiate oil deals helping both countries circumvent sanctions.

In an unrelated matter, the DEA records also indicate agents’ interest in Rodríguez’s possible involvement in allegedly corrupt deals between the government and Omar Nassif-Sruji, a relative of a longtime romantic partner of Rodríguez's, Yussef Nassif.

Nassif-Sruji did not respond to emails and text messages seeking comment and an attorney for Nassif denied his client was involved in any nefarious activity, pointing out that he hasn't been accused of any crime.

"He has the utmost respect and confidence in the acting president's vision for Venezuela and believes she is a true patriot who has committed her entire life to the betterment of the Venezuelan people," the attorney, Jihad M. Smaili, said in a statement. “The insinuations that Mr. Nassif is currently involved in any untoward relationship with the acting president are false.”

Taken together, the DEA investigations underscore how power has long been exercised in Venezuela, which is ranked as the world’s third most corrupt country by Transparency International. For Rodríguez, they also represent something of a razor-sharp sword over her head, breathing life to Trump’s threat soon after Maduro’s ouster that she would “pay a very big price, probably bigger than Maduro” if she didn’t fall in line. The president added that he wanted her to provide the U.S. “total access” to the country’s vast oil reserves and other natural resources.

“Just being a leader in a highly corrupted regime for over a decade makes it logical that she is a priority target for investigation,” said David Smilde, a Tulane University professor who has studied Venezuela for three decades. “She surely knows this, and it gives the U.S. government leverage over her. She may fear that if she does not do as the Trump administration demands, she could end up with an indictment like Maduro.”

—-

Mustian reported from New York.

—-

Contact AP’s global investigative team at Investigative@ap.org or https://www.ap.org/tips/.

—-

This story is part of an ongoing collaboration between The Associated Press and FRONTLINE (PBS) that includes an upcoming documentary.

Venezuela's acting President Delcy Rodriguez makes a statement to the press at Miraflores presidential palace in Caracas, Venezuela, Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)

Venezuela's acting President Delcy Rodriguez smiles while delivering a statement at Miraflores presidential palace in Caracas, Venezuela, Wednesday, Jan. 14, 2026. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)

Venezuela's acting President Delcy Rodriguez arrives at the National Assembly in Caracas, Venezuela, Thursday, Jan. 15, 2026. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)