MANDALAY, Myanmar (AP) — Thae Mama Swe stood atop a pile of earthquake rubble in the monsoon rain as she watched an excavator below tear away at the concrete and rebar, while a second machine scooped the wreckage away.

It has been a daily ritual for the 47-year-old seamstress for five months, ever since a 7.7-magnitude earthquake centered in Myanmar brought down a 10-story condo and office building with her son inside. Nearly 200 bodies have been recovered from the site, including seven in the past week, but not his.

“If it were possible, I would exchange my life for his,” she said, her glasses wet with rain and her eyes swollen with tears.

The March 28 disaster that killed more than 3,800 people unfolded as Myanmar was already mired in a civil war, in which armed militias and pro-democracy forces are fighting the military-led government that seized power from the democratically elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi in 2021.

During a rare trip into the disaster zone, The Associated Press recently witnessed a country laboring to rebuild the roads, temples, hospitals, schools and government buildings needed for a society to function, while still grappling with the deadly divisions that have torn the nation apart.

The military allowed AP to report on the quake damage in the capital, Naypyitaw, and in the country's second-largest city, Mandalay — both areas firmly under its control. Official representatives accompanied the team to all sites.

All sides declared a ceasefire immediately after the earthquake, but the fighting never really stopped.

Military airstrikes and artillery attacks have continued, including on civilian targets and in areas affected by the earthquake, said Tom Andrews, the U.N.-appointed human rights expert for Myanmar. The attacks have slowed or halted the delivery of humanitarian aid to many areas. Meanwhile, insurgents have also attacked the military.

Even before the quake, the United Nations estimated that more than 3.5 million people had been displaced from their homes due to the fighting, and some 20 million were in need of assistance. Now, five months on, the military continues to restrict aid to areas outside its control, the U.N. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights said in a report this week.

“The junta has to stop killing people, it’s as simple as that,” Andrews said. “And they need to stop obstructing aid.”

Authorities deny that the military, known as the Tatmadaw, is holding up any aid and maintain that any airstrikes are in response to attacks on them from militia groups.

“We are only doing it in self-defense when the enemy comes and attacks us,” Zaw Tun Oo, the head of the protocol department of the Myanmar Foreign Ministry, told AP outside the ministry building, which itself was badly damaged by the earthquake.

Several aid organizations operating inside Myanmar that need the regime's permission to be there declined to comment on the situation.

The destruction of infrastructure such as roads and bridges has added to the challenge of bringing aid to the worst-hit areas. Hospitals, schools, places of worship and other community buildings have been damaged or destroyed, leaving few places where people can seek shelter or care.

Along the main highway from the country's largest city, Yangon, to Mandalay, toppled temples and buckled sections of pavement serve as a constant reminder of the quake's destructive power. Military engineers have erected temporary bridges to allow traffic to pass over rivers where spans have been destroyed. Damaged bridges that remain standing are being repaired.

Violence is never far away, with pro-democracy forces attacking along the road even after the earthquake.

Across the Mandalay region, nearly 29,000 homes, 5,000 Buddhist pagodas and 43 bridges were either completely or partially destroyed, according to official statistics.

Myanmar continues to trade with China, Russia and others, but Western sanctions have hurt an already struggling economy. That means authorities have fewer means at their disposal to rebuild while also enduring shortages of supplies and equipment.

Recent cuts to foreign aid by U.S. President Donald Trump's administration have also left both U.N. organizations and other groups operating inside Myanmar struggling to meet humanitarian needs.

The lack of American logistical help has been especially acute, including the transport of aid and heavy equipment to remote areas, Andrews said. In the past, such assistance was routine.

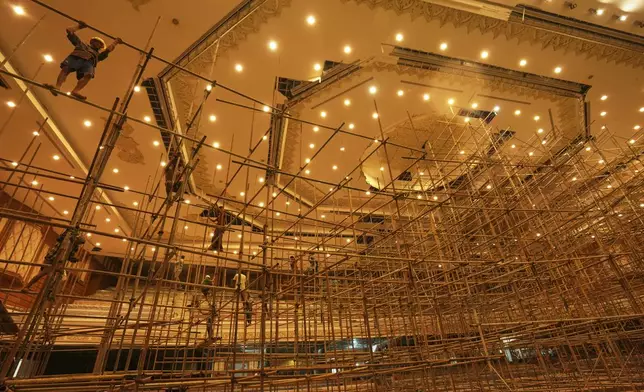

At the parliament complex in Naypyitaw, up to 500 people are working day and night, seven days a week, on the five most important buildings that were damaged. Crews are repairing collapsed ceilings and walls and shoring up foundations so they will be usable in time for elections scheduled for the end of December. Scaffolding fills entire chambers.

It's seen as symbolically important to have the main parliament buildings ready for new lawmakers to gather in their first session. Critics say the elections are a sham to normalize the military takeover, and several opposition organizations, including armed resistance groups, have said they will try to derail them.

Following the dissolution of Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy party, which won a landslide victory in 2020, the opposition maintains elections cannot be considered fair or representative. The military seized power before the NLD could begin its second five-year term.

The National Unity Government, established by elected lawmakers who were barred from taking their seats, did not respond to a request for comment.

Elsewhere in the capital, teams of about 40 workers, primarily women, toil largely by hand to repair roads at about a dozen sites. The laborers carry baskets of large stones on their heads and shoulders and dump them to form the foundation, followed by loads of gravel that are topped with asphalt.

As the reconstruction progresses, officials say Myanmar needs help from other countries that have experience constructing earthquake-resistant buildings.

Aye Min Thu, the chief of the Mandalay division of Myanmar's disaster management agency, said with that assistance, the country could “build a resilient society” so that "future generations will not be easily destroyed."

At the site of one of the capital's largest hospitals, nothing remains but rusted rebar, plastic pipes and concrete, sorted into piles to be taken away. Hospital beds and furniture are stacked under a shelter for possible reuse, but the engineer in charge of the project, Thin Thin Swe, said it's not yet clear whether Ottara Thiri Hospital will be rebuilt.

The 47-year-old lost two friends — the hospital's accountant and its pharmacist — when the main lobby caved in.

“I still pray for them every day,” she said.

At the site where Thae Mama Swe's son worked, Mandalay's fire chief Kyaw Ko Ko said the recovery work has been difficult on his teams, especially when they come across the bodies of children, who “could easily be my own relatives or family members."

As she watched the slow recovery effort continue, Thae Mama Swe talked about the guilt she feels over her son's death since he was only working in the building that collapsed because she encouraged him to return to Mandalay. Her greatest hope is to recover his body, an essential part of Buddhist religious rites.

“I will never give up hope for that,” she said. “Then his soul will be free, and I can live peacefully.”

Laborers work inside a parliament building that was damaged in the March 28 earthquake in Naypyitaw, Myanmar, Thursday, Aug. 28, 2025. (AP Photo/Aung Shine Oo)

Laborers work at a building in the Mandalay University compound that was damaged in the March 28 earthquake, in Mandalay, Myanmar, Wednesday, Aug. 27, 2025. (AP Photo/Aung Shine Oo)

A backhoe clears an area near the parliament building that was damaged in the March 28 earthquake in Naypyitaw, Myanmar, Thursday, Aug. 28, 2025. (AP Photo/Aung Shine Oo)

Thae Mama Swe stands at the site of Sky Villa, a 10-story condo that collapsed during the March 28 earthquake, in Mandalay, Myanmar, Wednesday, Aug. 27, 2025. (AP Photo/Aung Shine Oo)

A fire officer works at the site of the Sky Villa, a 10-story condo that collapsed during the March 28 earthquake, in Mandalay, Myanmar, Wednesday, Aug. 27, 2025. (AP Photo/Aung Shine Oo)