BURLINGTON, Vt. (AP) — As a Greek immigrant who came to the United States in 1956, Nectar Rorris never imagined the Vermont restaurant and music club he opened 50 years ago would become synonymous with Phish, but he credits the jam band with giving Nectar’s a national spotlight and making it a place sought out by local and traveling musicians alike.

“Phish made Nectar's,” the 86-year-old Rorris said recently.

Click to Gallery

FILE - From left to right, members of the band Phish, Page McConnell, Jon Fishman, Trey Anastasio and Mike Gordon appear in the press room after performing at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony, Monday, March 15, 2010 in New York. (AP Photo/Peter Kramer, File)

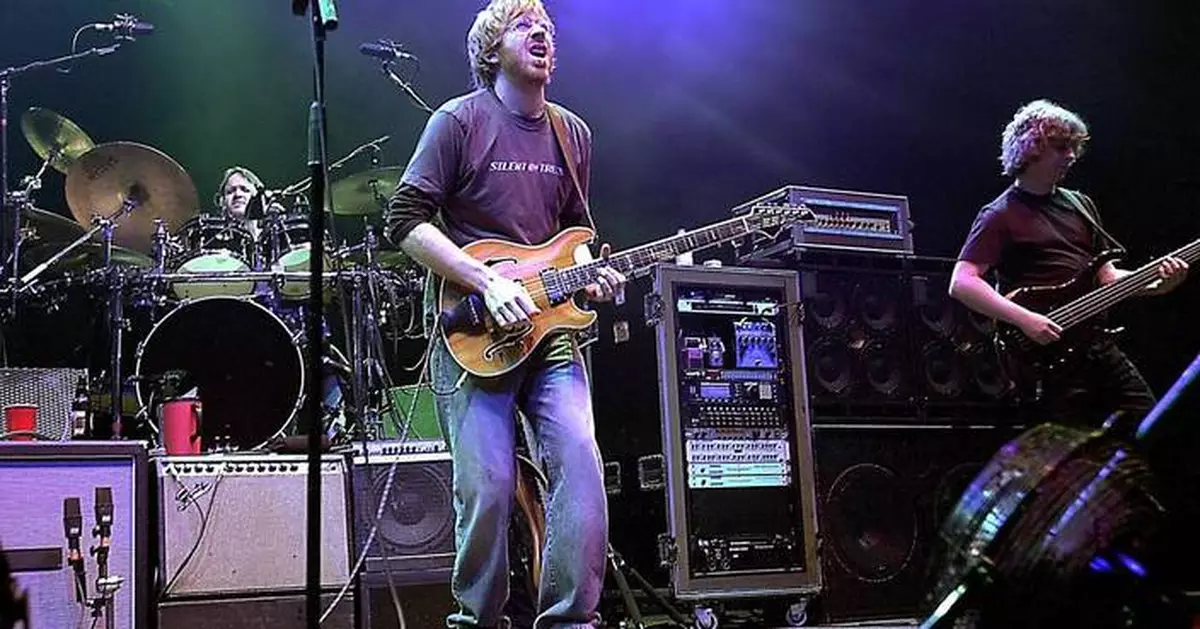

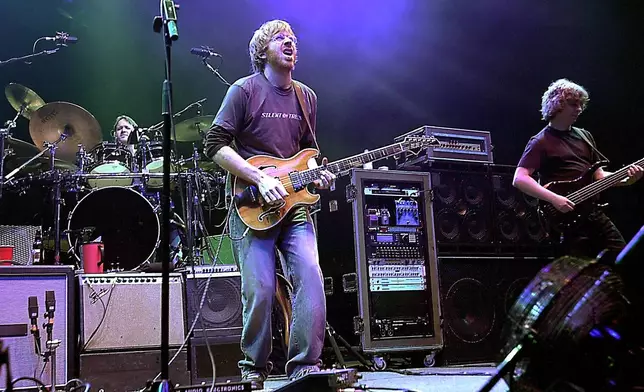

FILE - Phish's Trey Anastasio, left, drummer Jon Fishman, center, and bassist Mike Gordon perform with the band at Keyspan Park in the Brooklyn borough of New York Thursday, June 17, 2004. (AP Photo/Chad Rachman, File)

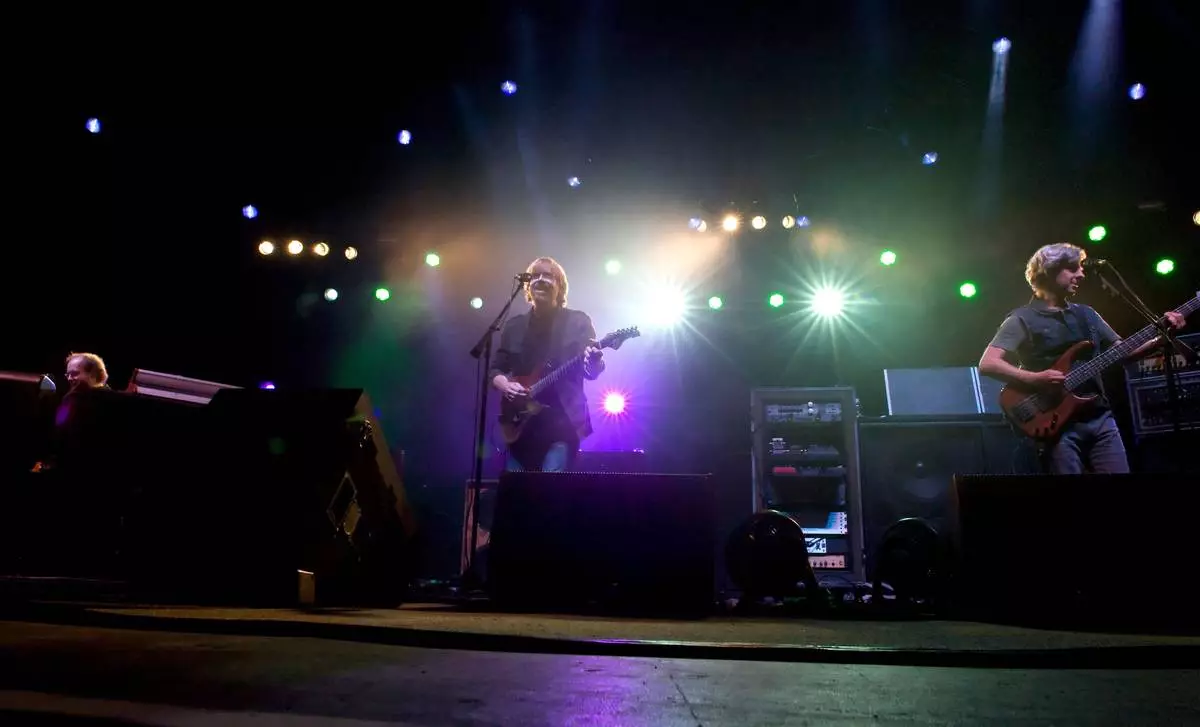

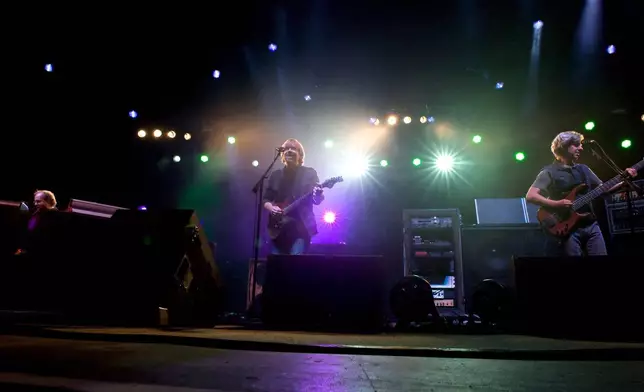

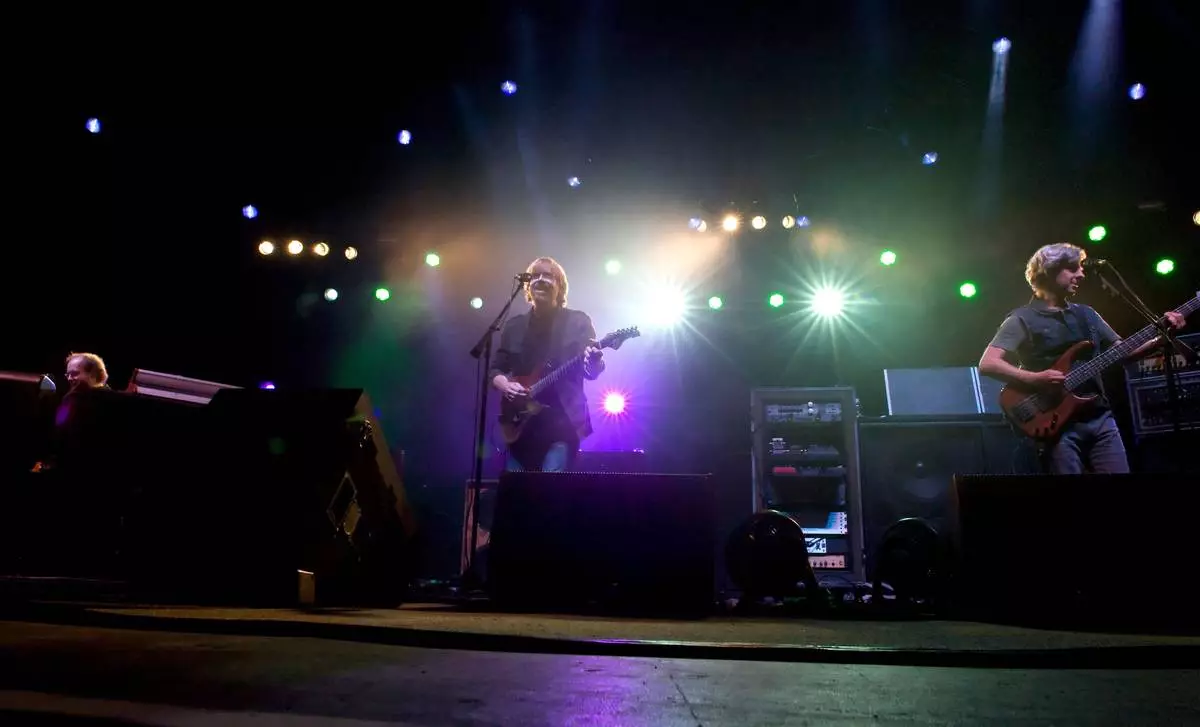

FILE - Phish band members Page McConnell, Trey Anastasio, Mike Gordon, from left, performs during their benefit concert at the Champlain Valley Exposition in Essex Junction, Vt, on Wednesday, Sept. 14, 2011. (AP Photo/Alison Redlich, File)

People walk by Nectar's, the music club where jam band Phish got their start, in downtown Burlington, Vt., Wednesday, July 30, 2025. (AP Photo/Amanda Swinhart)

A plaque and posters that used to hang on the walls inside Nectar's music club in Burlington, where the jam band Phish got its start, are displayed in Essex, Vt., Thursday, Oct. 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Amanda Swinhart)

Nectar Rorris, one of the original owners of Nectar's music club in Burlington, Vt., looks at a plaque featuring a photo of the jam band Phish and a message dedicating their 1992 album "A Picture of Nectar" to Rorris and the venue, Thursday, Oct. 2, 2025 in Essex, Vt. (AP Photo/Amanda Swinhart)

Nectar Rorris, one of the original owners of Nectar's music club in Burlington, Vt., looks at a plaque featuring a photo of the jam band Phish and a message dedicating their 1992 album "A Picture of Nectar" to Rorris and the venue, Thursday, Oct. 2, 2025 in Essex, Vt. (AP Photo/Amanda Swinhart)

Nectar's, the music club where jam band Phish got their start, is shown in downtown Burlington, Vt., Wednesday, July 30, 2025. (AP Photo/Amanda Swinhart)

FILE - The group Phish, drummer Jon Fishman, guitarist Trey Anastasio, center, and bassist Mike Gordon, perform in this Dec. 31, 2002 file photo at New York's Madison Square Garden. (AP Photo/Stephen Chernin, File)

Phish meanwhile credits Rorris with their early success, giving them a stage to experiment on when they were starting out in the early '80s.

But now, the iconic Burlington venue that fostered a community of diverse artists has closed its doors, despite negotiations to keep the music going.

Nectar’s announced it was taking a pause in June, citing “immense challenges affecting both downtown Burlington and the local live music and entertainment scene.” Several weeks later, the venue announced on social media that it was closing for good. The post immediately drew hundreds of comments and tributes from musicians, former employees and fans.

“As a musician, you want to move up. You get a few fans; you go to a bigger club. That’s what Nectar’s was,” said Chris Farnsworth, who covers Burlington’s music scene for the Vermont newspaper Seven Days.

Farnsworth noted that the venue — a brick building with a neon sign — “holds a very important place” in Phish lore. The band's 1992 record was titled “A Picture of Nectar” as a tribute to the venue and to Rorris, who gave the fledgling band a residency for nearly two years.

“The guys from Phish were very good to us,” said Alex Budney, who started at Nectar’s in 2001 as a cook when he was 19, making their famous gravy fries and later working almost every job in the building over 20 years.

“My college band would play there on Monday nights and it would be like nobody there. But the keyboard player from Phish would come down in a snowstorm and sit at the bar and watch us play and talk to us,” Budney said.

Phish bassist Mike Gordon, who still lives in the area, even popped in during singer-songwriter Maggie Rose’s sound check last September and joined her band for two songs that night. Rose had rerouted her tour just to be able to play at Nectar’s.

“It was the perfect excuse to go to this legendary venue in this amazing, creative, artistic town,” said Rose. “The lore of Nectar’s did not disappoint. It truly was just one of those surreal moments.”

Phish declined to comment on the venue's closing, as did the current owner.

Rorris opened Nectar's in 1975 with two partners.

“They borrowed money from their parents. I did the same and we closed the deal,” he said.

In the beginning, Rorris focused solely on the restaurant, leaving the music booking and finances to his partners. Eventually, his partners wanted to move on, so the three sold the business to a new owner who only lasted six months. Rorris decided to buy the business back and ran it by himself until 2003, when he decided to sell for personal reasons.

“The bands were real thrilled to see that I was taking it back and that I was going to hire them back," he said. "From then, it took off.”

Though Phish made Nectar’s famous, the venue also hosted such artists as Vermont’s own Grace Potter and Anais Mitchell, B.B. King, Spacehog, Blind Melon and the Decemberists. And it was known for regular music series including Metal Mondays; Dead Set Tuesdays — a tribute to The Grateful Dead; blues, jazz and reggae nights; comedy shows and Sunday Night Mass, a production showcasing electronic artists from around the world.

Nectar’s ownership and management changed repeatedly, but it remained a place to discover new music. Budney said Nectar's supported emerging artists with residency opportunities to play weekly for a month or more and build a fan base.

“We’d provide tools for bands to make it,” he said.

The venue itself ultimately couldn't make it as costs rose and construction in downtown Burlington reduced foot traffic and turned away business. It's unclear what will happen to it next.

But those who played a role in the club’s history say its legacy is undeniable.

“Fifty years is an amazing run for a nightclub,” said Justin Remillard, who booked artists for Nectar’s electronic music series for 25 years. “The only constant is change, and what has happened with Nectar’s and the building closing, we have to figure out what’s next.”

FILE - From left to right, members of the band Phish, Page McConnell, Jon Fishman, Trey Anastasio and Mike Gordon appear in the press room after performing at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony, Monday, March 15, 2010 in New York. (AP Photo/Peter Kramer, File)

FILE - Phish's Trey Anastasio, left, drummer Jon Fishman, center, and bassist Mike Gordon perform with the band at Keyspan Park in the Brooklyn borough of New York Thursday, June 17, 2004. (AP Photo/Chad Rachman, File)

FILE - Phish band members Page McConnell, Trey Anastasio, Mike Gordon, from left, performs during their benefit concert at the Champlain Valley Exposition in Essex Junction, Vt, on Wednesday, Sept. 14, 2011. (AP Photo/Alison Redlich, File)

People walk by Nectar's, the music club where jam band Phish got their start, in downtown Burlington, Vt., Wednesday, July 30, 2025. (AP Photo/Amanda Swinhart)

A plaque and posters that used to hang on the walls inside Nectar's music club in Burlington, where the jam band Phish got its start, are displayed in Essex, Vt., Thursday, Oct. 2, 2025. (AP Photo/Amanda Swinhart)

Nectar Rorris, one of the original owners of Nectar's music club in Burlington, Vt., looks at a plaque featuring a photo of the jam band Phish and a message dedicating their 1992 album "A Picture of Nectar" to Rorris and the venue, Thursday, Oct. 2, 2025 in Essex, Vt. (AP Photo/Amanda Swinhart)

Nectar Rorris, one of the original owners of Nectar's music club in Burlington, Vt., looks at a plaque featuring a photo of the jam band Phish and a message dedicating their 1992 album "A Picture of Nectar" to Rorris and the venue, Thursday, Oct. 2, 2025 in Essex, Vt. (AP Photo/Amanda Swinhart)

Nectar's, the music club where jam band Phish got their start, is shown in downtown Burlington, Vt., Wednesday, July 30, 2025. (AP Photo/Amanda Swinhart)

FILE - The group Phish, drummer Jon Fishman, guitarist Trey Anastasio, center, and bassist Mike Gordon, perform in this Dec. 31, 2002 file photo at New York's Madison Square Garden. (AP Photo/Stephen Chernin, File)

CLEVELAND (AP) — It took only three starts for Shedeur Sanders to get his first 300-yard passing game in the NFL. However, it didn't end up giving the Cleveland Browns a victory.

Sanders passed for 364 yards and three touchdowns and also ran for a score, but an interception in the third quarter and a pair of miscues on 2-point conversions loomed large as the Tennessee Titans held on for a 31-29 victory Sunday.

“He fought throughout the game, which we knew he would," coach Kevin Stefanski said. "With any young player, there’s going to ups and downs, and I thought there were some really, really, really good moments. He’ll keep learning from some of the plays that he wants back, but some really good moments.”

Sanders, who fell to the fifth round in the draft, completed 23 of 42 passes. The 364 passing yards are the second-most by a rookie QB picked 144th overall or later since 1966. Jacksonville's Gardner Minshew, the 178th pick in 2019, passed for 374 yards against Carolina.

The NFL said Sanders joined Cincinnati’s Joe Burrow as the only rookie QBs with at least 350 passing yards, three touchdown passes and a rushing score in a game.

He also joined Cam Newton (2011 with Carolina), Tom Ramey (1987 with New England) and Vinny Testaverde (1987 with Tampa Bay) as the only quarterbacks to throw for at least 350 yards and two touchdowns passes along with a rushing TD in at least one of his first three career starts.

It was the 10th 300-yard game by a Browns rookie QB, and the first since Baker Mayfield had 376 yards in the 2018 regular-season finale at Baltimore.

The Browns had four pass plays of at least 30 yards, their most since last year's Monday night game at Denver in Week 13. In three starts, Sanders has eight of the Browns' 10 pass plays of at least 30 yards.

Sanders’ father, Pro Football Hall of Famer Deion Sanders, was in attendance. Coach Prime was at his son’s first NFL start on Nov. 23 at Las Vegas, but missed last week’s home game against San Francisco.

Sanders' best pass of the day was a 60-yard touchdown to Jerry Jeudy with 2:47 remaining in the second quarter to put the Browns up 17-14. Sanders threw a well-timed ball on a post route to Jeudy, who hauled it in at the Titans 41 and outraced Darrell Baker and Amani Hooker to the end zone.

It also showed that Sanders and Jeudy are developing more of a rapport after the two had a sideline spat last week against San Francisco that was shown on television.

“Obviously me and Jerry had that dispute or whatever last week. But I have faith in him, he has faith in me, and everybody put everything aside,” Sanders said. “It was truly exciting being able to connect with him, because I know the season hasn’t gone the way he wanted to this year."

Sanders was 9 of 14 for 180 yards and two touchdowns in the first half. He struggled in the third quarter, going 3 of 10 for 47 yards and an interception before nearly rallying Cleveland in the fourth with a rushing touchdown and a 7-yard TD pass to Harold Fannin Jr. after falling behind 31-17.

Besides the interception, which came on a scramble and was just heaved into the middle of the field before it was picked off, Sanders fumbled the exchange from center Luke Wypler on the first 2-point attempt. Wypler came in at center during the third quarter after starter Ethan Pocic suffered what could be a season-ending Achilles tendon injury.

Sanders, though, was not on the field for the second and potential tying 2-point conversion. Running back Quinshon Judkins lined up to take the direct snap and appeared as if he was going to pitch it to wide receiver Gage Larvadain on an end around.

The pitch never happened, and Judkins' pass was batted away, allowing the Titans to hold on for only their second win of the season.

“I would wish I would always have the ball in my hand, but that’s not what football is,” Sanders said. "I know we practiced something, and we executed it in practice, and we just didn’t seem to this day. So, I would never go against, you know, kind of like what the call was or anything.”

Cam Ward, the top pick in April's draft, saw Sanders on the field postgame after the two trained together leading up to the draft.

Other Titans also were impressed with Sanders' performance, which happened on a snowy day on Cleveland's lakefront with conditions not suitable for passing.

“He’s a competitor, man. He’s been a competitor his whole life," defensive tackle Jeffery Simmons said. "I told him that’s his team now, and you’re going to be a star in this league.”

AP NFL: https://apnews.com/hub/nfl

Tennessee Titans quarterback Cam Ward, left, and Cleveland Browns quarterback Shedeur Sanders (12) greet each other after an NFL football game in Cleveland, Sunday, Dec. 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Sue Ogrocki)

Cleveland Browns quarterback Shedeur Sanders (12) throws a pass under pressure from Tennessee Titans defenders in the second half of an NFL football game in Cleveland, Sunday, Dec. 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Sue Ogrocki)

Cleveland Browns' Shedeur Sanders (12) and Teven Jenkins (74) celebrate a touchdown in the first half of an NFL football game against the Tennessee Titans in Cleveland, Sunday, Dec. 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Sue Ogrocki)

Cleveland Browns quarterback Shedeur Sanders (12) runs the ball for a touchdown as Tennessee Titans defensive tackle T'Vondre Sweat (93) gives chase in the second half of an NFL football game in Cleveland, Sunday, Dec. 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Sue Ogrocki)

Cleveland Browns quarterback Shedeur Sanders (12) visits with his father Deion Sanders, right, during warmups before an NFL football game against the Tennessee Titans in Cleveland, Sunday, Dec. 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Sue Ogrocki)