“That man, that young man — I forgive him.”

Erika Kirk softly spoke those words about the gunman accused of assassinating her husband, conservative activist Charlie Kirk, as she struggled to hold back tears last month during his memorial service.

Her public declaration inspired another. Hollywood actor Tim Allen said he was so moved by her words that he was forgiving the drunken driver who caused his father’s death 60 years ago. Barely two weeks after Charlie Kirk’s death, members of a Michigan congregation made public that they too were forgiving a gunman, the one who had just attacked their church, killing four people and injuring eight others.

Their high-profile acts of forgiveness are all the more remarkable given the politically charged and highly polarizing climate gripping the U.S. It has pushed people of faith to contemplate what forgiveness means, particularly in the face of violence, trauma and unspeakable grief, and whether it could shift public consciousness toward compassion.

While some see a glimmer of hope in this moment, others are skeptical. Miroslav Volf, professor of theology at Yale Divinity School, said he views President Donald Trump’s response to Erika Kirk’s words — that he hates his opponents — as the more typical sentiment.

"Erika Kirk’s gesture is the outlier,” he said. “It was an extraordinary act of courage. But it was also telling that (Trump’s) response got the bigger reaction from the crowd at the memorial. You have to wonder about these two very different responses. How do we find space for grace when we are so at odds that we cannot recognize humanity on the other side of the divide?”

California pastor Jack Hibbs, who leads Calvary Chapel Chino Hills and is a friend of the Kirks, called her words an “incredibly powerful” message of hope for the shooter, and in keeping with the family's deep commitment to the Gospel, which commands Christians to forgive even their enemies.

“The Bible warns us that bitterness, when left alone, can grow up in and destroy your heart,” Hibbs said. “So forgiveness was given to us by God to set us free from what’s been done to us.”

The Rev. Thomas Berg, visiting professor at the McGrath Institute for Church Life at the University of Notre Dame, said he hopes Erika Kirk’s gesture “ignites some kind of meaningful national conversation about forgiveness.”

He said forgiveness is not a one-time event, but a process that takes time and work. Berg, who counsels victims of sex abuse in the Catholic Church, warns that it should never be coerced but authentically given — an act that he says has the power to heal the deepest wounds.

He would like to see more public expressions of forgiveness, which could serve as a balm for the country.

“I hope this is not a passing moment,” he said. “The dynamic of forgiveness throws a wrench into the dysfunction of our partisan divides and our inability to have a reasonable exchange of ideas.”

Dave Butler, a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and science fiction writer based in Utah, believes forgiveness is a mandate for all Christians, as his church teaches. He started a crowdfunding initiative for the family of the Michigan shooter who opened fire on the Latter-day Saints congregation, which as of this week, had raised a little over $388,000.

Butler said he started it because — in addition to the grieving church members who had lost loved ones in this mass shooting — there was the family of the gunman that was also traumatized.

“They also did not choose this,” he said. “Nevertheless, they are now short a husband and a father. If we’re not really thoughtful, we might be inclined to see them more as antagonists rather than victims. More than 10,000 people have contributed and they understand what they’re doing is an act of forgiveness.”

An often-cited modern example of forgiveness is the response of the Amish community around Nickel Mines, Pennsylvania, after a gunman killed five Amish schoolgirls and wounded five more in 2006 before taking his own life. Local Amish immediately expressed forgiveness for the killer and supported his widow.

Amish are part of the wider Anabaptist movement, which puts heavy emphasis on Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount, containing some of his most radical and counter-cultural sayings — to love enemies, live simply, bless persecutors, turn the other cheek and to endure sufferings joyfully. In it, Jesus says God will only forgive those who forgive others.

While many outside the Anabaptists' world have endorsed their beliefs about forgiveness — which they also voiced for Haitian kidnappers of Anabaptist missionaries in 2021 — others say the picture is more complex. Advocates for victims of sexual abuse in Anabaptist communities say victims and their families are often forced to reconcile with abusers after the latter make a confession and undergo a brief period of discipline.

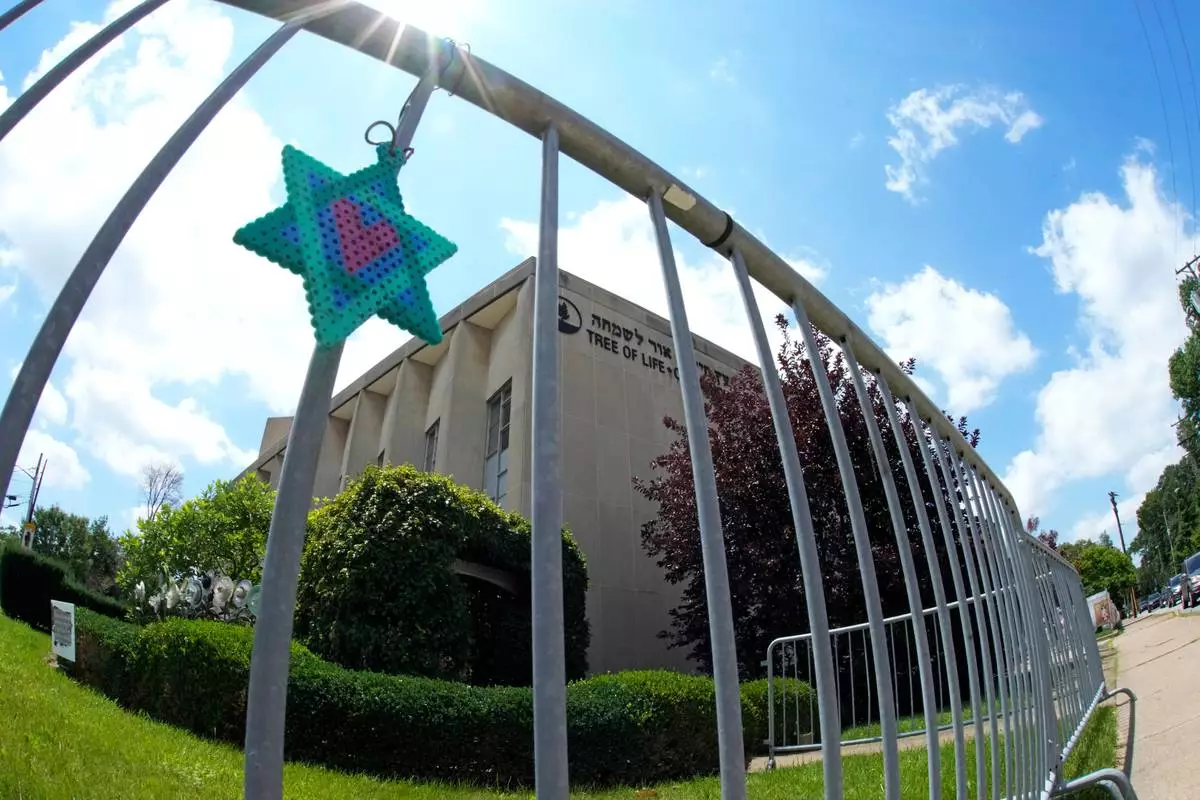

The Jewish perspective on forgiveness is different in that it requires the perpetrator to seek forgiveness from the person who has been wronged, said Rabbi Jeffrey Myers. He heads Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh where 11 people from three congregations were killed after a gunman attacked it during Shabbat services on Oct. 27, 2018.

“For me, it’s complicated because there are 11 dead people who cannot be sought for forgiveness,” Myers said, adding that he cannot offer forgiveness because the perpetrator — who faces execution — did not show remorse.

“While the perpetrator has received a measure of justice as outlined by the judicial process, it didn’t give me closure because those 11 people are gone," Myers said. "There is nothing that makes that pain go away.”

What gives him some comfort is being able to help other congregations that are going through similar trauma. Myers said he was grateful to have received that support from the Rev. Eric Manning, pastor of Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, a historically Black church where a self-proclaimed white supremacist shot and killed nine congregants on June 17, 2015 — including the church’s pastor at the time.

“Today, as someone who belongs to that club no one should belong to, I view it as my sacred obligation to help,” Myers said. “Even if I can help one person, that’s gratifying, that feels healing.”

Peg Durachko, whose husband Dr. Richard Gottfried, a dentist, was one of the victims in the synagogue shooting, said that as a Catholic, she looked to Pope John Paul II for inspiration as she read about how he visited the imprisoned man who shot him and offered forgiveness.

“I recognize (the gunman) as a child of God who made bad choices to lead him in that direction,” she said. “I’m not his judge, God is. I want him to have eternal life. I don’t harbor hate or ill wishes to anyone, including him. I don’t want to carry this baggage of hate.”

AP journalist Peter Smith in Pittsburgh contributed to this report.

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

FILE - Erika Kirk speaks at a memorial for her husband Charlie Kirk, Sept. 21, 2025, at State Farm Stadium in Glendale, Ariz. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson, file)

FILE - A Star of David hands from a fence outside the dormant landmark Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh's Squirrel Hill neighborhood on July 13, 2023. (AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar/File)