GÜIRIA, Venezuela (AP) — One was a fisherman struggling to eke out a living on $100 a month. Another was a career criminal. A third was a former military cadet. And a fourth was a down-on-his-luck bus driver.

The men had little in common beyond their Venezuelan seaside hometowns and the fact all four were among the more than 60 people killed since early September when the U.S. military began attacking boats that the Trump administration alleges were smuggling drugs. President Donald Trump and top U.S. officials have alleged the craft were being operated by narco-terrorists and cartel members bound with deadly drugs for American communities.

The Associated Press learned the identities of four of the men – and pieced together details about at least five others – who were slain, providing the first detailed account of those who died in the strikes.

In dozens of interviews in villages on Venezuela’s breathtaking northeastern coast, from which some of the boats departed, residents and relatives said the dead men had indeed been running drugs but were not narco-terrorists or leaders of a cartel or gang.

Most of the nine men were crewing such craft for the first or second time, making at least $500 per trip, residents and relatives said. They were laborers, a fisherman, a motorcycle taxi driver. Two were low-level career criminals. One was a well-known local crime boss who contracted out his smuggling services to traffickers.

The men lived on the Paria Peninsula, in mostly unpainted cinderblock homes that can go weeks without water service and regularly lose power for several hours a day. They awoke to panoramic views of a national park's tropical forests, the Gulf of Paria's shallows and the Caribbean's sparkling sapphire waters. When the time came for their drug runs, they boarded open-hulled fishing skiffs that relied on powerful outboard motors to haul their drugs to nearby Trinidad and other islands.

The residents and relatives interviewed by the AP requested anonymity out of fear of reprisals from drug smugglers, the Venezuelan government or the Trump administration. They said they were incensed that the men were killed without due process. In the past, their boats would have been interdicted by the U.S. authorities and the crewmen charged with federal crimes, affording them a day in court.

The U.S. government “should have stopped them,” a man’s relative said.

It has been difficult for relatives to learn much about their dead loved ones because criminal gangs and the Venezuelan government have long repressed the flow of information in the region.

Venezuelan officials have blasted the U.S. government over the strikes, and the nation’s ambassador to the U.N. called the attacks “extrajudicial executions.” They have also steadfastly denied that drug traffickers operate in the country and have yet to acknowledge that any of its citizens have been killed in boat strikes. Spokespeople for Venezuela’s government did not respond to a request for comment.

The Trump administration has justified the strikes by declaring drug cartels to be “ unlawful combatants ” and said the U.S. is now in an “armed conflict” with them. Trump has said each sunken boat has saved 25,000 American lives, presumably from overdoses. The boats, however, appear to have been transporting cocaine, not the far more deadly synthetic opioids that kill tens of thousands of Americans each year.

Sean Parnell, the Pentagon’s chief spokesman, said in a statement to the AP that the Defense Department has “consistently said that our intelligence did indeed confirm that the individuals involved in these drug operations were narco-terrorists, and we stand by that assessment.”

So far, the U.S. military has blown up 17 vessels, killing more than 60 people. Nine of the craft were targeted in the Caribbean, and at least three of those had departed from Venezuela, according to the Trump administration. The military is striking the boats at the same time the administration is applying increasing pressure on Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. The Justice Department doubled a reward for his arrest to $50 million, and the U.S. military has built up an unusually large force in the Caribbean Sea and the waters off Venezuela and has flown pairs of supersonic, heavy bombers along the country’s coast.

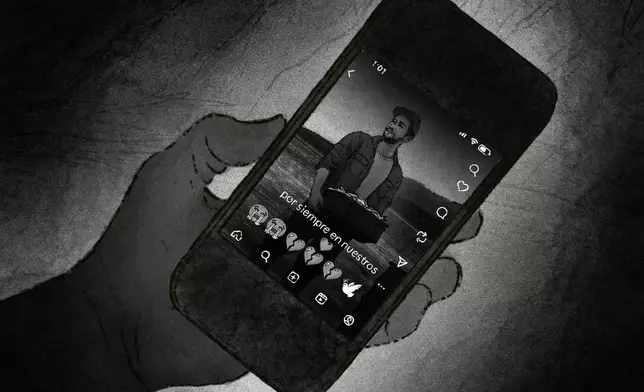

Relatives and acquaintances said they have confirmed the deaths through word-of-mouth and inexplicit social media posts that sought to convey information about the dead men without drawing the attention of Venezuelan authorities. They have also made what they described as reasonable deductions: The men have not returned phone calls or texts in weeks, or reached out to say they were OK; Venezuelan authorities, residents said, have also searched some of the homes of the dead men.

“I want an answer, but who can I ask?" said a relative of one of the men. “I can’t say anything.”

A native of Güiria, a village on the southeast side of the peninsula, Robert Sánchez dropped out of school as a teenager and like many others in the region became a fisherman like his father, according to friends and relatives. The 42-year-old was considered among the peninsula's best pilots, they said, having spent the better part of three decades mastering the area's currents and winds, so much so he could navigate the waters at night without instruments.

As part of hired crews, the father of four spent his days fishing for snapper, kingfish and dogfish. The fisherman wanted to save enough money to buy a 75-horsepower boat engine so he could operate his own boat and not work for others. It was a dream Sánchez knew he was likely to never realize, relatives said: Most of his income — about $100 a month — went to feed his children.

He was not alone in that situation.

The peninsula is part of Sucre state, one of Venezuela’s poorest. Sucre was once home to several fish processing plants, an auto assembly plant and a large public university, all of which offered well-paying jobs. Most have shuttered. The peninsula is dotted by the unfulfilled promises of 26 years of a self-described socialist government, including an abandoned shipyard and the rusted infrastructure meant for a natural gas complex.

With its proximity to the Caribbean Sea, the area is a popular transit hub for cocaine making its way from Colombia to Trinidad and other Caribbean islands before heading to Europe. Colombian cocaine destined for the U.S. is generally smuggled out of Colombia through the Pacific coast.

The larger economic pressures — and Sánchez’s goal of owning a boat engine — are what pushed the fisherman to accept an offer to help traffickers navigate the tricky waters he knew so well, friends and relatives said.

Sánchez had just finished offloading a day’s catch last month when he told his mother he would be taking a short trip and would see her in a couple of days. They had no idea where he was going.

After seeing clips on social media that mentioned his death, relatives broke the news to his mother, but not until after ensuring she had taken her blood pressure medication. Sánchez's youngest son, a third grader, could not accept for days that his father was gone. He kept asking adults if his father could have survived the explosion, noting he might still be at sea.

No, the adults told the boy. His father was gone.

Luis “Che” Martínez was killed in the first strike. A burly 60-year-old, Martínez was a longtime local crime boss, and he made most of his living smuggling drugs and people across borders, according to several people who knew him.

He had been jailed by Venezuelan authorities on human-trafficking charges after a boat he had operated capsized in December 2020, killing about two dozen people, law enforcement officials said at the time. Among those who died in the accident were two of his sons and a granddaughter, relatives told the AP. The AP was not able to determine the disposition of his criminal case, but Martínez was eventually released from custody and returned to smuggling people and drugs, according to acquaintances.

Though they detested what he did for a living — and the control Martínez and similar criminals exerted over their villages — several residents said they appreciated how Martínez contributed annually to the town’s festival of the Virgin of the Valley, the patroness of fishermen, and he spent lavishly in local shops and restaurants. He also bet heavily on cockfights, a popular pastime, a bird breeder said.

Martínez was killed, a relative and several acquaintances said, in the first known U.S. strike, which took place Sept. 2. Trump quickly took to social media to claim the vessel had departed from Venezuela and had been carrying drugs. The 11-man crew, the president said, had been members of the Tren de Aragua gang. He said all of the men were killed and also posted a short video clip of a small vessel appearing to explode in flames.

Martínez’s relatives said they did not believe the underworld figure was a member of that gang.

They said they have been provided no information from the Venezuelan government about his fate. They figured it out when they came across a photo of a body that had washed ashore in Trinidad. The photo had been shared on social media and messaging apps and depicted a badly mutilated body. The people familiar with Martínez said they knew instantly the stout corpse was Martínez because, on his left wrist, was strapped one of his most treasured belongings: an ostentatious watch.

Dushak Milovcic, 24, was drawn to crime by the adrenaline rush and money, so much that he dropped out of the country’s National Guard Academy, according to those who knew him. He started as a lookout for smugglers, they said. Though he had no experience at sea, he eventually won a promotion to the more lucrative and coveted jobs on drug-running boats.

It’s not clear how many trips he had undertaken before he was killed last month.

Juan Carlos “El Guaramero” Fuentes had operated a transit bus for several years but was facing dire financial circumstances when it had broken down. The government had been unable — or unwilling — to fix it. That meant he was losing money because bus drivers in Venezuela typically pocket a portion of the fares, making it nearly impossible for him to feed and clothe his family.

Villagers said they were not surprised that Fuentes, who had no nautical experience, turned to smuggling to make ends meet. The higher-level traffickers who typically crewed such boats had been staying ashore to avoid being targeted by U.S. missiles. In their place, villagers said, they had been increasingly hiring novices like Fuentes.

Fuentes told friends he had been nervous about his first smuggling run, knowing it would be filled with risks from weather, rival gangs, even the U.S. military. The September trip had gone surprisingly smoothly, he told friends, and he readily agreed to join another crew. Fuentes was killed in a missile strike last month, friends said, the precise one unknown.

—-

Konstantin Toropin contributed from Washington.

—

This story was supported by funding from the Walton Family Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

—-

Contact the AP’s global investigative team at Investigative@ap.org or https://www.ap.org/tips/

(AP Illustration / Peter Hamlin)

(AP Illustration / Peter Hamlin)

(AP Illustration / Peter Hamlin)

(AP Illustration / Peter Hamlin)

(AP Illustration / Peter Hamlin)

(AP Illustration / Peter Hamlin)