PORTLAND, Maine (AP) — It's the Maine one, not the main one — a 208-year-old, Maine-based publication that farmers, gardeners and others have relied on for planting guidance and weather predictions will publish for the final time.

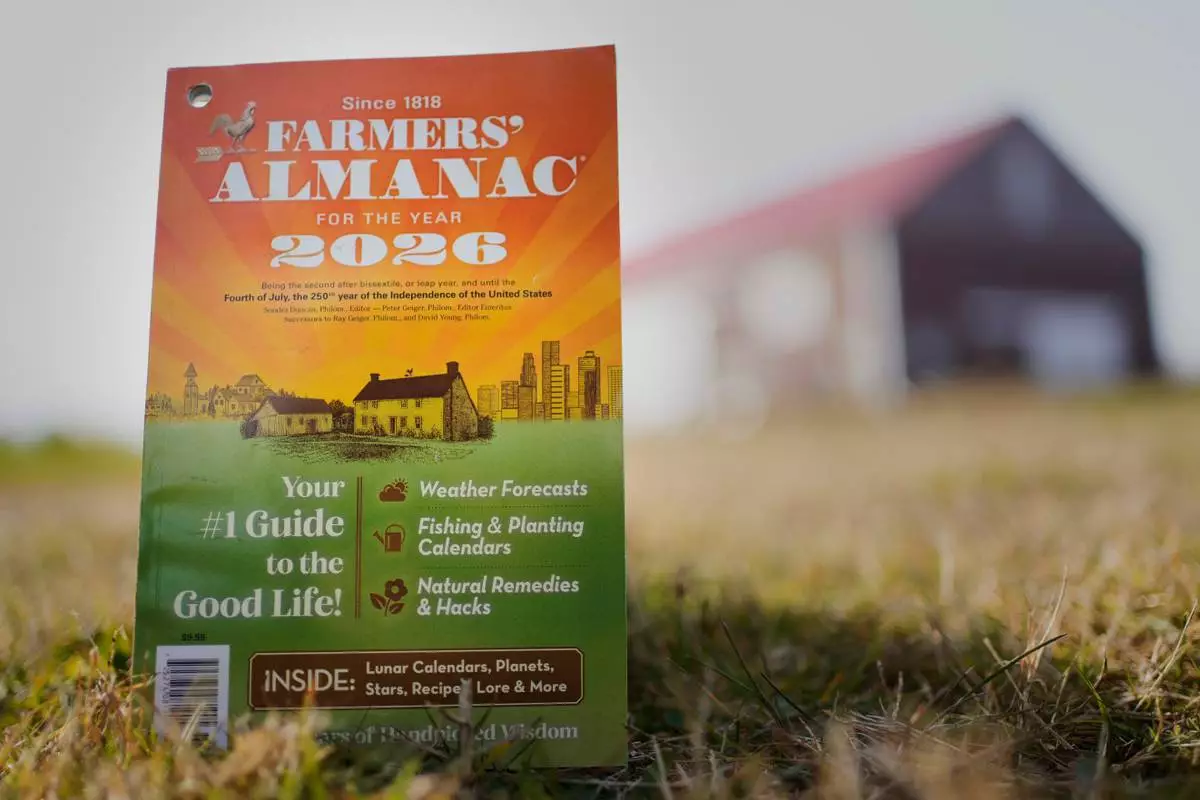

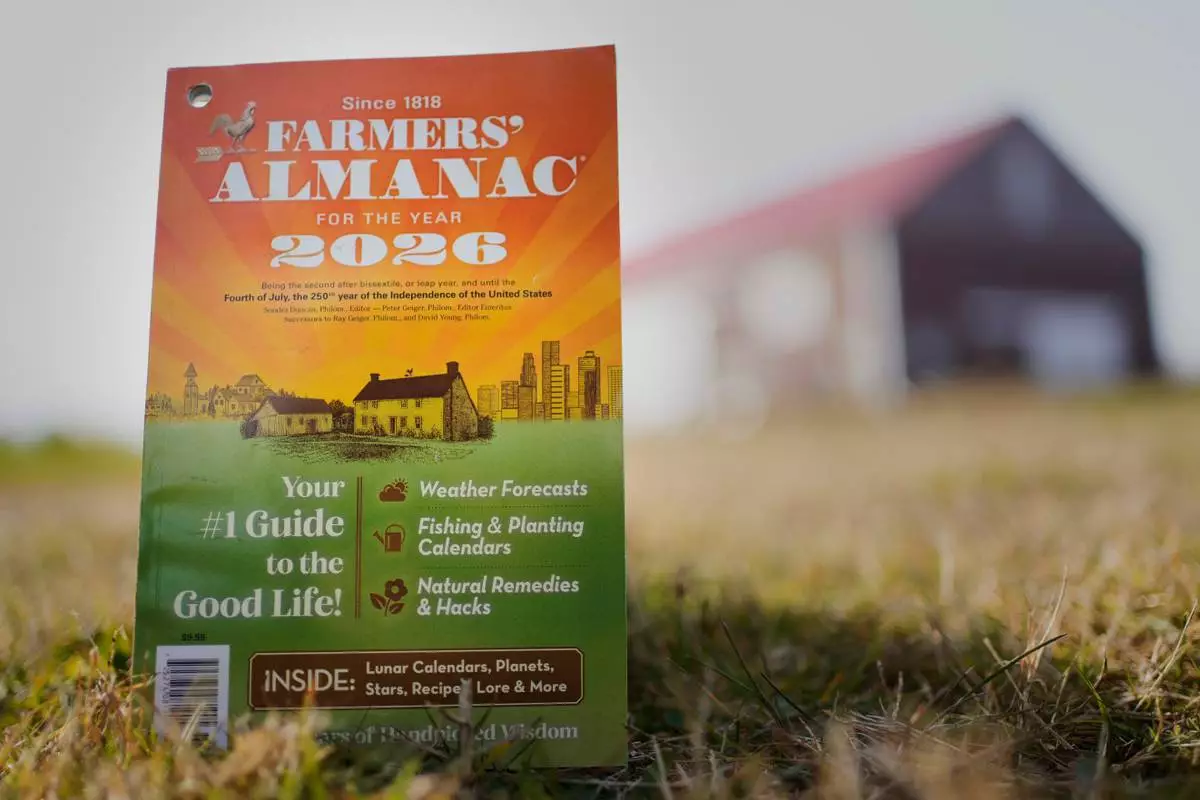

The Farmers' Almanac, not to be confused with its older, longtime competitor, The Old Farmer’s Almanac in neighboring New Hampshire, said Thursday that its 2026 edition will be its last. The almanac cited the growing financial challenges of producing and distributing the book in today's “chaotic media environment.” Access to the online version will cease next month.

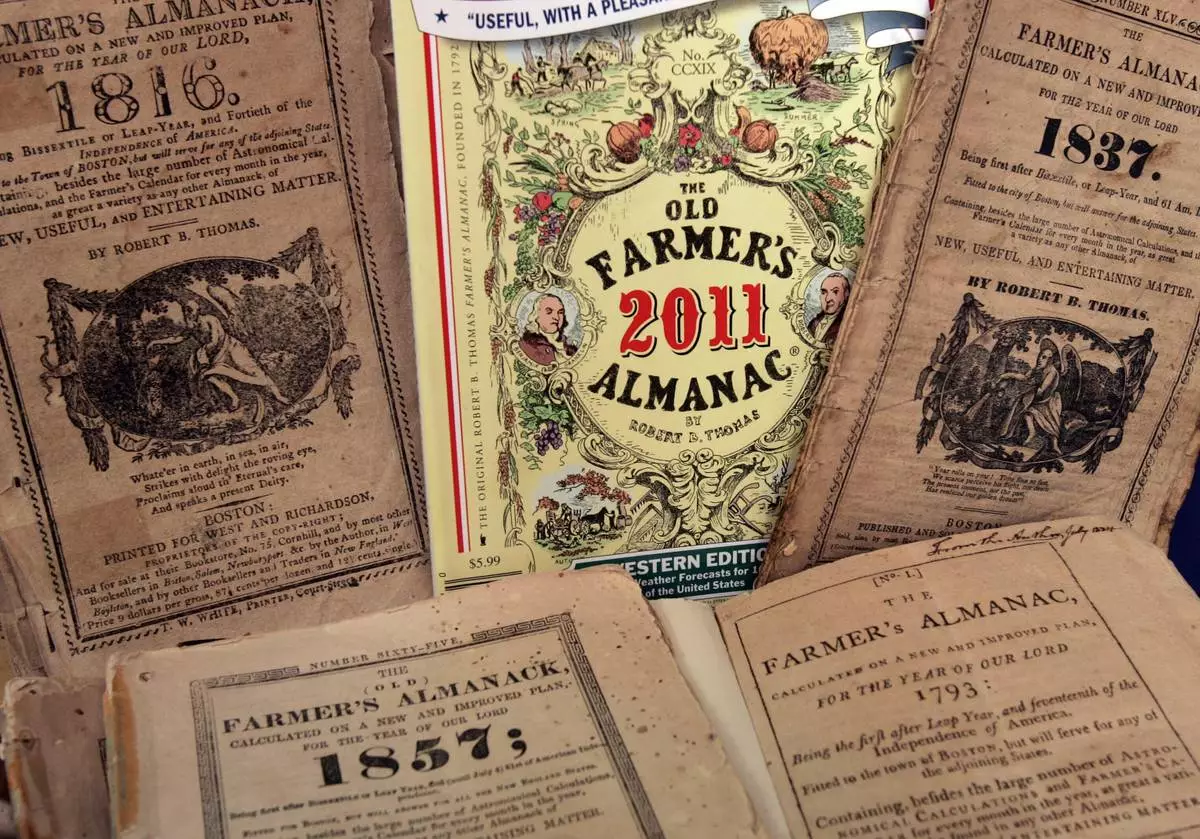

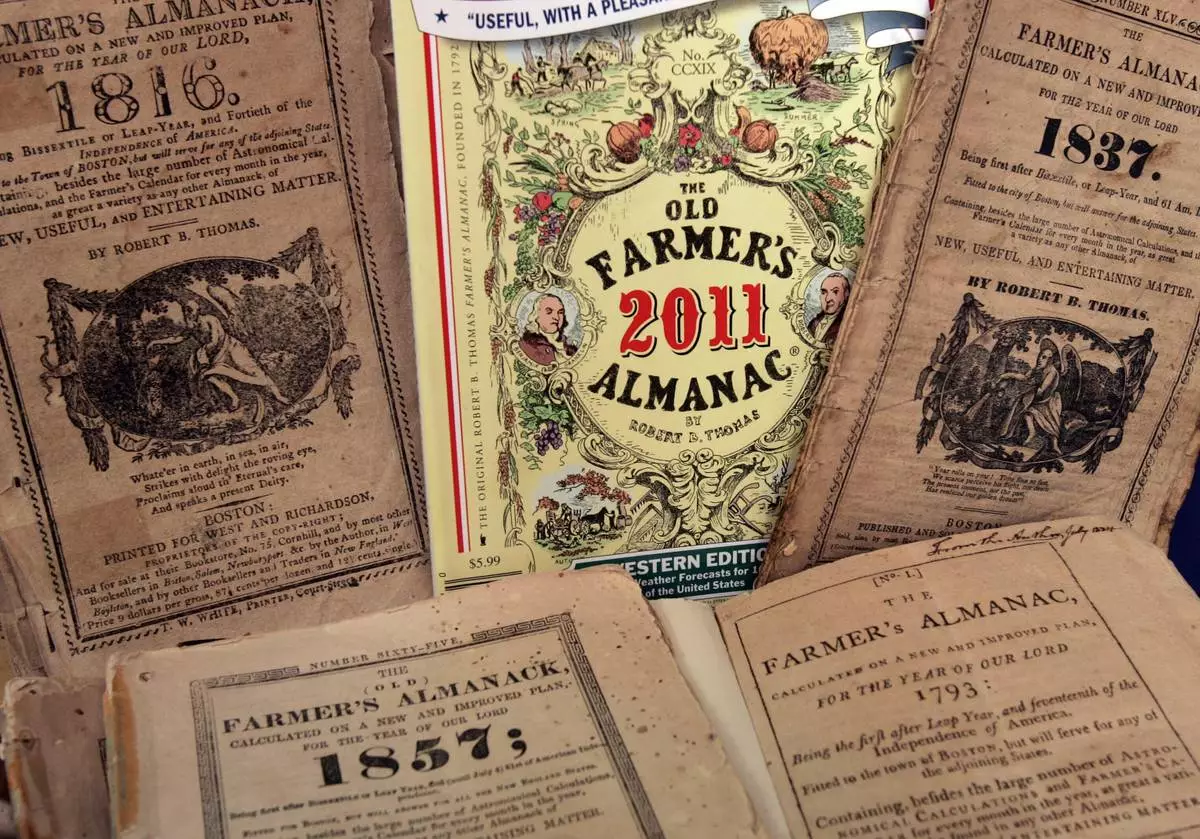

The Farmers’ Almanac was first printed in 1818 and the Old Farmer's Almanac started in 1792, and it's believed to be the oldest continually published periodical in North America. Both almanacs used secret formulas based on sunspots, planetary positions and lunar cycles to generate long-range weather forecasts.

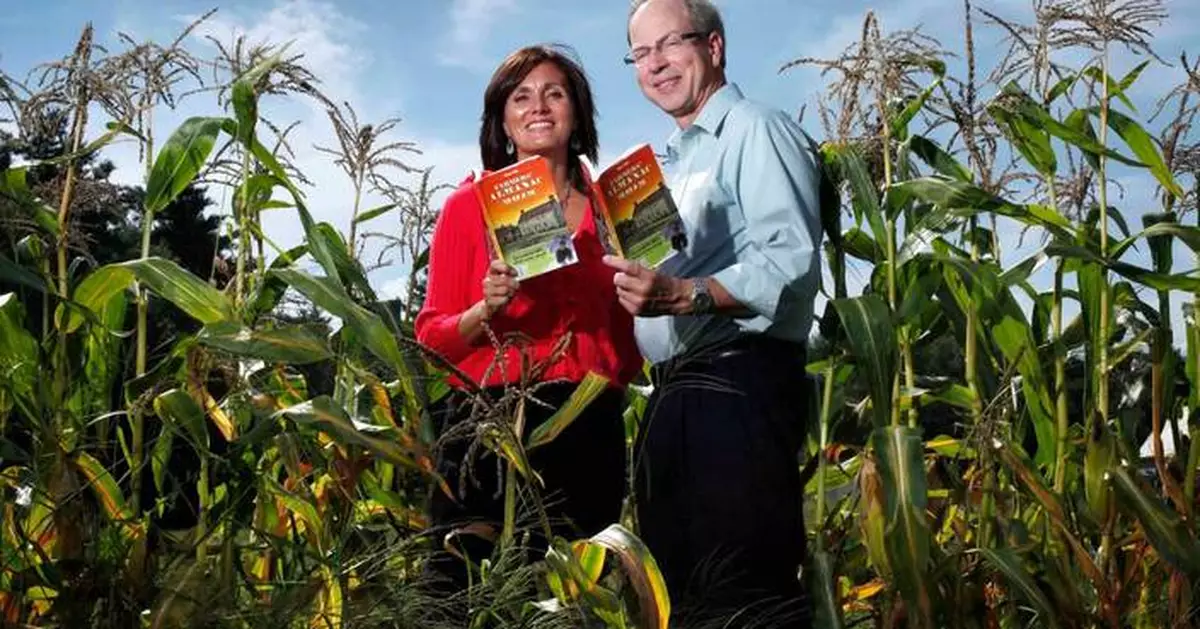

“It is with a heavy heart,” Editor Sandi Duncan said in a statement, “that we share the end of what has not only been an annual tradition in millions of homes and hearths for hundreds of years, but also a way of life, an inspiration for many who realize the wisdom of generations past is the key to the generations of the future.”

Editors at the other publication noted there's been some confusion between the two. “The OLD Farmer's Almanac isn't going anywhere,” they posted online.

The two publications come from an era where hundreds of almanacs served a nation of farmers over time. Most were regional publications and no longer exist. The Farmers’ Almanac was founded in New Jersey and moved its headquarters to Lewiston, Maine, in 1955.

They contain gardening tips, trivia, jokes, and natural remedies, such as catnip as a pain reliever and elderberry syrup as an immune booster. But its weather forecasts make the most headlines.

Scientists sometimes disputed the accuracy of the predictions and the reliability of the secret formula. Studies of the almanacs' accuracy have found them to be a little more than 50% accurate, or slightly better than random chance.

The almanac was a “quaint relic” with a special kind of charm, but its use as a forecasting tool was debatable, said Val Kiddings, a senior fellow at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation and a longtime researcher of science and agriculture.

“It might have had some value looking back, as a historical indicator,” Giddings said, “but I never took any of its prognostications at all seriously.”

Readers, saddened to hear the news, posted online about how they used it in their families for generations as a guide to help them plant gardens and follow the weather.

Julie Broomhall in San Diego, California, told The Associated Press in a social media post that she’s used the Farmers’ Almanac for years to decide when to take trips and plant flowers.

She said she planned a three-month, cross-country trip last year by reading the almanac. On one leg of it, she left Oklahoma the day before a prediction for a major snowstorm in the area. It snowed.

“I missed several I-40 mishaps because of the predictions,” she wrote.

In 2017, when the Farmers' Almanac reported a circulation of 2.1 million in North America, its editor said it was gaining new readers among people interested in where their food came from and who were growing fresh produce in home gardens. It developed followers online and sent a weekly email to readers in addition to its printed editions.

Many of these readers lived in cities, prompting the publication to feature skyscrapers as well as an old farmhouse on its cover.

Among Farmers’ Almanac articles from the past is one from 1923 urging folks to remember “old-fashioned neighborhoodliness” in the face of newfangled technology like cars, daily mail and telephones. Editors urged readers in 1834 to abandon tobacco and, in 1850, promoted the common bean leaf to combat bedbugs.

The almanac had some forward-thinking advice for women in 1876, telling them to learn skills to avoid being dependent on finding a husband. “It is better to be a woman than a wife, and do not degrade your sex by making your whole existence turn on the pivot of matrimony,” it counseled.

McCormack reported from Concord, New Hampshire.

FILE - The latest edition of the Old Farmer's Almanac is mixed in with older editions, Sept. 1, 2010, in Dublin, N.H. (AP Photo/Jim Cole)

A copy of the final edition of the Farmers' Almanac is seen, Friday, Nov. 7, 2025, in Alexander, Maine. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty)

FILE - Farmers' Almanac editor Sondra Duncan and publisher Peter Geiger pose in a corn field with the 2012 edition of the almanac, Aug. 24, 2011, in Auburn, Maine. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty, File)

JERUSALEM (AP) — Over two dozen families from one of the few remaining Palestinian Bedouin villages in the central West Bank have packed up and fled their homes in recent days, saying harassment by Jewish settlers living in unauthorized outposts nearby has grown unbearable.

The village, Ras Ein el-Auja, was originally home to some 700 people from more than 100 families that have lived there for decades.

Twenty-six families already left on Thursday, scattering across the territory in search of safer ground, say rights groups. Several other families were packing up and leaving on Sunday.

“We have been suffering greatly from the settlers. Every day, they come on foot, or on tractors, or on horseback with their sheep into our homes. They enter people’s homes daily,” said Nayef Zayed, a resident, as neighbors took down sheep pens and tin structures.

Israel's military and the local settler governing body in the area did not respond to requests for comment.

Other residents pledged to stay put for the time being. That makes them some of the last Palestinians left in the area, said Sarit Michaeli, international director at B’Tselem, an Israeli rights group helping the residents.

She said that mounting settler violence has already emptied neighboring Palestinian hamlets in the dusty corridor of land stretching from Ramallah in the West to Jericho, along the Jordanian border, in the east.

The area is part of the 60% of the West Bank that has remained under full Israeli control under interim peace accords signed in the 1990s. Since the war between Israel and Hamas erupted in October 2023, over 2,000 Palestinians — at least 44 entire communities — have been expelled by settler violence in the area, B'Tselem says.

The turning point for the village came in December, when settlers put up an outpost about 50 meters (yards) from Palestinian homes on the northwestern flank of the village, said Michaeli and Sam Stein, an activist who has been living in the village for a month.

Settlers strolled easily through the village at night. Sheep and laundry went missing. International activists had to begin escorting children to school to keep them safe.

“The settlers attack us day and night, they have displaced us, they harass us in every way” said Eyad Isaac, another resident. “They intimidate the children and women.”

Michaeli said she’s witnessed settlers walk around the village at night, going into homes to film women and children and tampering with the village’s electricity.

The residents said they call the police frequently to ask for help — but it seldom arrives. Settlement expansion has been promoted by successive Israeli governments over nearly six decades. But Benjamin Netanyahu’s far-right government, which has placed settler leaders in senior positions, has made it a top priority.

That growth has been accompanied by a spike in settler violence, much of it carried out by residents of unauthorized outposts. These outposts often begin with small farms or shepherding that are used to seize land, say Palestinians and anti-settlement activists. United Nations officials warn the trend is changing the map of the West Bank, entrenching Israeli presence in the area.

Some 500,000 Israelis have settled in the West Bank since Israel captured the territory, along with east Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip, in the 1967 Mideast war. Their presence is viewed by most of the international community as illegal and a major obstacle to peace. The Palestinians seek all three areas for a future state.

For now, displaced families of the village have dispersed between other villages near the city of Jericho and near Hebron further south, said residents. Some sold their sheep and are trying to move into the cities.

Others are just dismantling their structures without knowing where to go.

"Where will we go? There’s nowhere. We’re scattered,” said Zayed, the resident, “People’s situation is bad. Very bad.”

An Israeli settler herds his flock near his outpost beside the Palestinian village of Ras Ein al-Auja in the West Bank, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Mahmoud Illean)

A Palestinian resident of Ras Ein al-Auja village, West Bank burns trash, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Mahmoud Illean)

Palestinian children play in the West Bank village of Ras Ein al-Auja, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Mahmoud Illean)

Palestinian residents of Ras Ein al-Auja village, West Bank pack up their belongings and prepare to leave their homes after deciding to flee mounting settler violence, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Mahmoud Illean)

Palestinian residents of Ras Ein al-Auja village, West Bank pack up their belongings and prepare to leave their homes after deciding to flee mounting settler violence, Sunday, Jan. 11, 2026. (AP Photo/Mahmoud Illean)