FRANCONIA, N.H. (AP) — For more than two decades, Susan Bushby, a 70-year-old housekeeper from a rural ski town in New Hampshire's White Mountains, took comfort in knowing she only had a short drive to reach the community health center.

The lodge-like medical building, which sits on a hill overlooking town, was like a second home for Bushby and many other patients. The front desk staff knew their names and never missed a chance to celebrate a birthday or anniversary. Staff photos of the wilderness that makes the place such a draw hung on the walls, and bumping into a neighbor in the waiting room was routine.

But last month, the Ammonoosuc Community Health Services location in Franconia, a town of around 1,000 people, closed for good.

Officials blamed cuts in Medicaid, the federal program that millions of low-income Americans rely on for health care. The 1,400 patients, almost half of them older and some facing serious health challenges like cancer and early-stage dementia, must now drive at least 10 miles (16 kilometers) along rural roads to reach the nearest health center, which also is near a regional hospital. A second center is twice as far.

“I was very disturbed. I was downright angry,” said Bushby, who was brought to tears as she discussed the challenges of starting over at a new health center. “I just really like it there. I don’t know, I’m just really going to miss it. It’s really hard for me to explain, but it’s going to be sad.”

The closure of the Franconia center reflects the financial struggles facing community health centers and rural health care systems more broadly amid Medicaid cuts and a feared spike in health insurance rates. The government shutdown, which ended last week, was driven by a Democratic demand to extend tax credits, which ensure low- and middle-income people can afford health insurance through the Affordable Care Act, or ACA.

Marsha Luce, whose family moved from the Washington, D.C., area in 2000, is especially concerned about the impact on her 72-year-old husband, a former volunteer firefighter who has had his left ear and part of his jaw removed due to cancer. He also has heart and memory issues.

She worries about longer waits to see his doctor and the loss of relationships built up over decades in Franconia.

“It’s going to be hard,” she said. “But it’s a relationship that’s going to be missed. It’s a relationship that you can talk to people and you tell them something and you go, yeah, well, I’ve had cancer. Oh, let’s see. Oh, yeah. There it is in your chart. Do you know what I mean?”

More than 100 hospitals closed over the past decade, according to the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, a policy and advocacy group, and more than 700 more hospitals are at risk of closure. A branch of the HealthFirst Family Care Center, a facility in Canaan, New Hampshire, also announced it was closing at the end of October due in part to “changes in Medicaid reimbursement and federal funding” for these facilities.

“Because of these Medicaid cuts, we’re going to see rural hospitals, in particular, hit hard,” New Hampshire Sen. Maggie Hassan, a Democrat, told The Associated Press. “And obviously, the failure to extend the ACA tax credits right now is going to compound the problem. … These providers are going to see more and more uninsured patients. And that means they’re going to have to make really difficult decisions.”

The sustainability of the centers is critical because they serve as the nation’s primary care safety net, treating patients regardless of insurance coverage or ability to pay.

Though federally-funded community health centers like the one in Franconia have expanded their reach in recent years, treating 1 in 10 Americans and 1 in 5 rural Americans, they’ve often done so in the face of major financial constraints, according to data from the National Association of Community Health Centers.

On average, the centers are losing money — relying heavily on cash reserves, making service changes and sometimes closing locations to stay afloat, NACHC found. Nearly half have less than 90 days' cash on hand, according to the association. The future is even more bleak, with at least 2 million community health center patients expected to lose Medicaid coverage by 2034 and 2 million more who are newly uninsured turning to the centers for care.

“There’s nothing left to trim without cutting into care itself,” said Peter Shin, the chief science officer at the association.

When President Donald Trump’s bill passed this summer, Ed Shanshala, the CEO of Ammonoosuc, knew he was in trouble.

A meticulous planner and strategist, Shanshala projected that his network of five New Hampshire health centers — which relies on more than $2 million in federal funding out of a $12 million budget — would face a $500,000 shortfall partly due to Medicaid funding cuts. He also expected work requirements in the bill and spikes in health insurance premiums to have an impact.

Shanshala knew he needed to make cuts to save his centers and zeroed in on Franconia because the building was leased, whereas Ammonoosuc owns the other facilities.

“We’re really left with no choice,” Shanshala said, adding the closure would save $250,000. Finding additional cuts is hard, given that the centers provide services to anyone under 200% of the federal poverty line, he said. If he cuts additional services, Shanshala fears some patients will end up in a hospital emergency room or “stop engaging in health care period.”

“To have to pull out of a community is devastating on a relational level,” he said. “People still have access to health care. We’ll help them with transportation, but it’s clearly a grieving process. Whenever a business leaves a community, regardless if it’s health care or something else, there’s an emotional fabric tear.”

The closure has brought little controversy. Just a lot of grief.

Most of the patients come from the small towns of Franconia, Easton, Lincoln and Sugar Hill, communities whose economies rely on hikers, skiers and leaf peepers. Many are older, sicker and more spread out than the rest of the state.

Luce, who volunteers at the local Head Start program and delivers food to schools in Franconia, said the closure has her mostly frustrated with politicians, adding that she wished lawmakers in Washington could “just live the way regular people live” for a few months.

“They would have a much different idea of what goes on in the real world,” she added.

Patients like Jill Brewer, the chair of the Franconia Board of Selectmen whose family has been going there for decades, worry about the future and whether the closure signals the gradual collapse of the health care system in this part of the state.

“Is this kind of the first domino to fall?” said Brewer, noting how disbanding the town's volunteer ambulance service in 2023 angered many residents.

“It definitely leaves you feeling pretty anxious that this is going to continue to kind of snowball and become an even bigger issue,” she added.

On the clinic's last day, it was business as usual — no balloons, no cakes, no farewell speeches. The staff were stoic as they tended to patients, three of whom came in for their physicals and four for checkups. Bushby, who had come to have her blood pressure checked, hugged a staffer as crews dismantled the clinic and wheeled out exam tables.

“I'll come see you, honey. I will,” Bushby said, hugging Diane LaDuke, a patient access specialist. “It's been such a joy coming here.”

Shastri reported from Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

An exam table is moved onto a trailer on the final day of operation at Ammonoosuc Community Health Services as the clinic closes for good, Thursday, Oct. 23, 2025, in Franconia, N.H. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty)

Marsha, left, and Kirk Luce, both patients at Ammonoosuc Community Health Services, eat dinner, Thursday, Oct. 23, 2025, at their home in Franconia, N.H. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty)

Fall foliage colors the scene near the Community Church, Tuesday, Oct. 21, 2025, in Sugar Hill, N.H., a rural area where the closure of a community health center is leaving residents without nearby medical care. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty)

Dr. Melissa Buddensee, left, meets with patient Susan Bushby at Ammonoosuc Community Health Services, Tuesday, Oct. 21, 2025, in Franconia, N.H., in the final days before the clinic closes for good. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty)

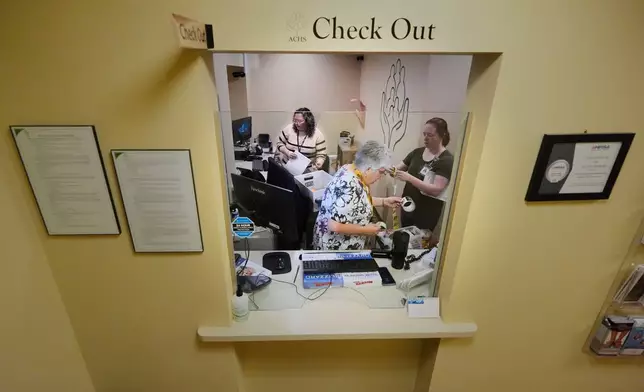

Employees at Ammonoosuc Community Health Services pack up the reception office as the clinic closes for good, Thursday, Oct. 23, 2025, in Franconia, N.H. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty)