MIDLAND, Texas (AP) — The Chinese government is using an increasingly powerful tool to control and monitor its own officials: Surveillance technology, much of it originating in the United States, an Associated Press investigation has found.

Among its targets is Li Chuanliang, a Chinese former vice mayor hunted by Beijing with the help of surveillance technology. Li’s communications were monitored, his assets seized and his movements followed in police databases. More than 40 friends and relatives — including his pregnant daughter — were identified and detained back in China.

Click to Gallery

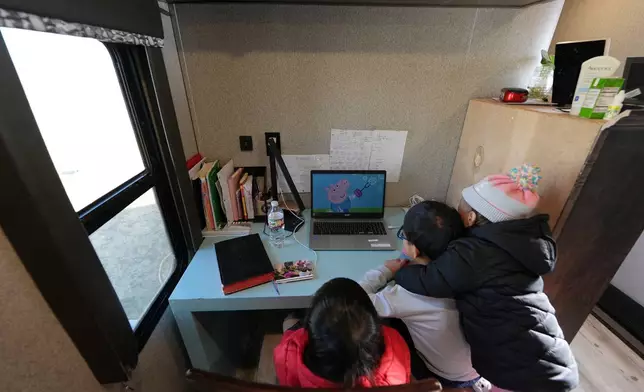

Siblings Mo Songhua, left, Mo Songen, center, and Mo Nika, right, from the Mayflower Church community watch, "Peppa Pig," to strengthen their English, inside their family's trailer in Midland, Texas, Jan. 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang adjusts his cap as he walks inside the Mayflower Church community in Midland, Texas, Jan. 19, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang sits in his car as he drives between buildings in the Mayflower Church community, Jan. 18, 2025, in Midland, Texas. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang harvests greens from a vegetable garden inside the Mayflower Church community in Midland, Texas, Jan. 19, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Zhang Qimiao plays with Li Chuanliang's German shepherd, Hardy, as the sun sets in the Mayflower Church community in Midland, Texas, Jan. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Lights shine inside the Mayflower Church hall, where members of the community gather for religious study or to enjoy downtime, in Midland, Texas, Jan. 19, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Nong Yitan plays foosball with other Mayflower Church kids inside the community hall in Midland, Texas, Jan. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

A Mayflower Church member walks out of the community's main hall, used for religious education and recreation, in Midland, Texas, Jan. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

The son of Mayflower Church Deacon, Luo Changcheng, who wasn't feeling well, naps in the room he shares with his parents, in Midland, Texas, Jan. 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

A bird flies from a window sill inside the Mayflower Church community hall in Midland, Texas, Jan. 19, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Mayflower Church member Chen Jingjing holds her daughter, Mo Nika, as she surveys the landscape from the porch of the family's trailer in Midland, Texas, Jan. 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Siblings Mo Songhua, left, Mo Songen, center, and Mo Nika, right, from the Mayflower Church community watch, "Peppa Pig," to strengthen their English, inside their family's trailer in Midland, Texas, Jan. 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Mayflower Church Deacon Luo Changcheng, wearing a tag with the American name Peter, gets a fist bump from his boss, Eric Smith, as he works at a car wash in Midland, Texas, Jan. 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang shops for meat at a supermarket in Midland, Texas, Jan. 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang, left, shares a meal with other members of the Mayflower Church, a Christian community which fled religious persecution in China, and American pastors who have welcomed the refugees, in Midland, Texas, Jan. 19, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Members of the Mayflower Church, a Christian community which fled religious persecution in China, pray at a church in Midland, Texas, Jan. 19, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang holds a Bible as he prays inside the Mayflower Church temple sanctuary in Midland, Texas, Jan. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang shows one of the few pictures he has of himself, at right, from when he was vice mayor of Jixi, China, in the Mayflower Church community in Midland, Texas, Jan. 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Pumpjacks work to extract oil as the sun rises in Midland, Texas, Jan. 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang greets his German shepherd, Hardy, as he returns from a trip to town from the Mayflower Church community in Midland, Texas, Jan. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

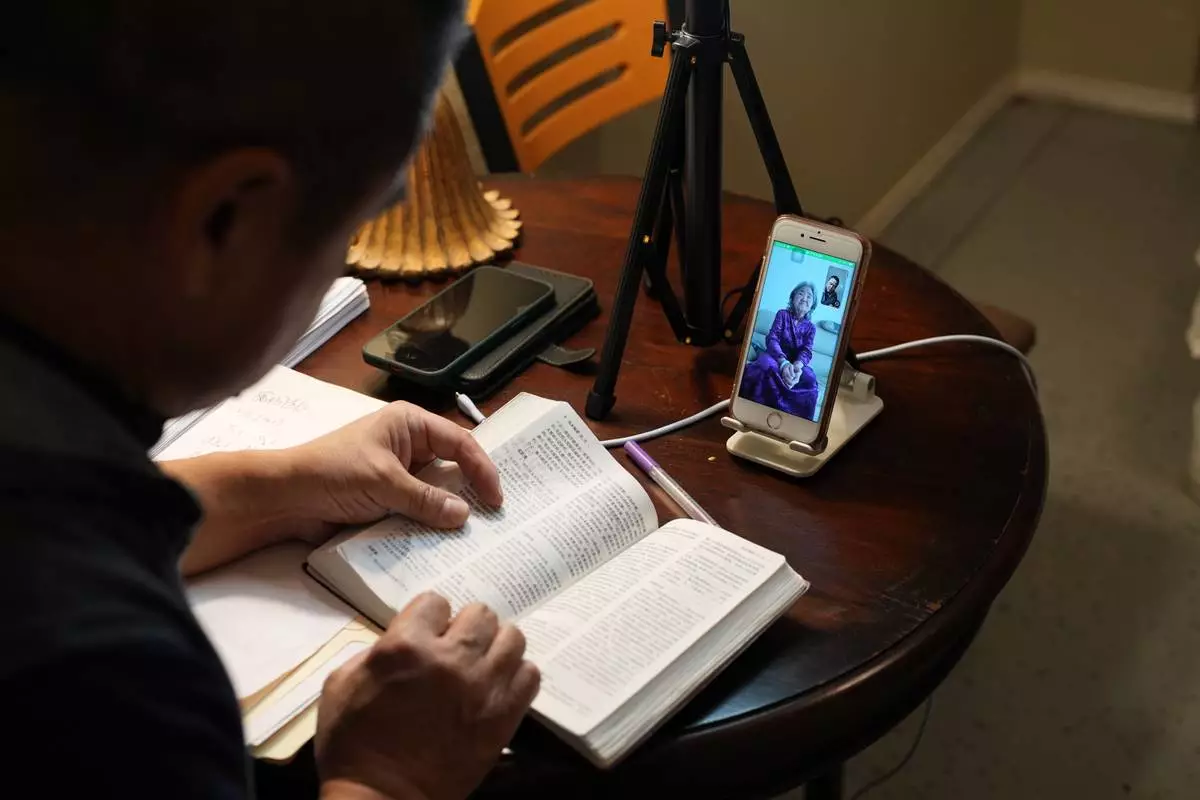

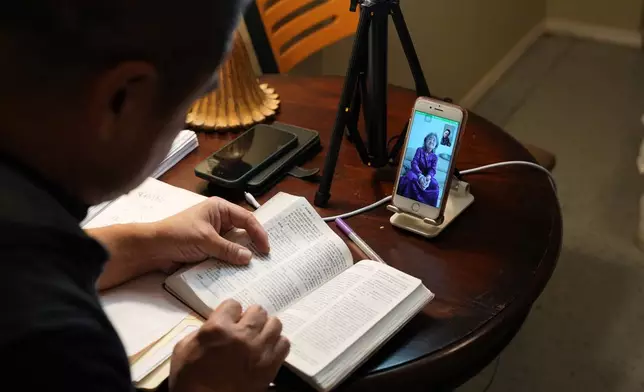

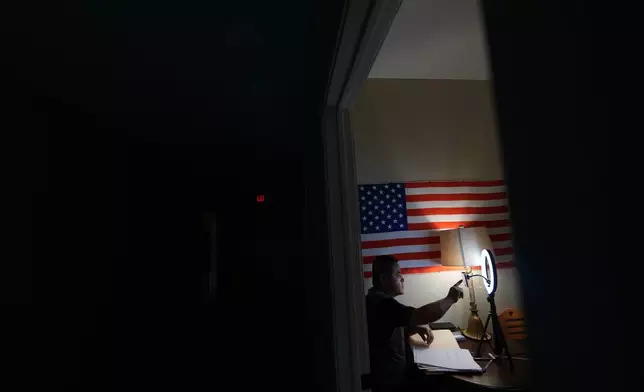

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang reads the Bible to his elderly mother, Shen Shuzi, who is back in China, over a video call in Midland, Texas, Jan. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

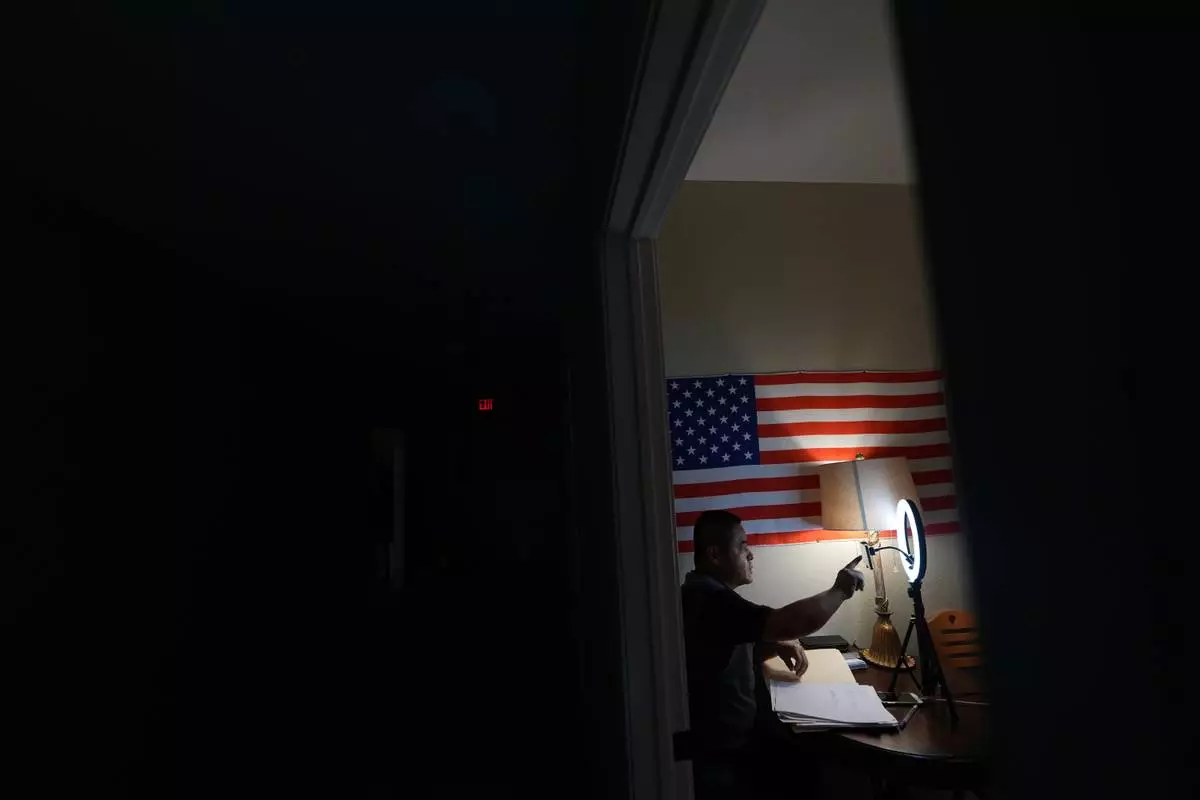

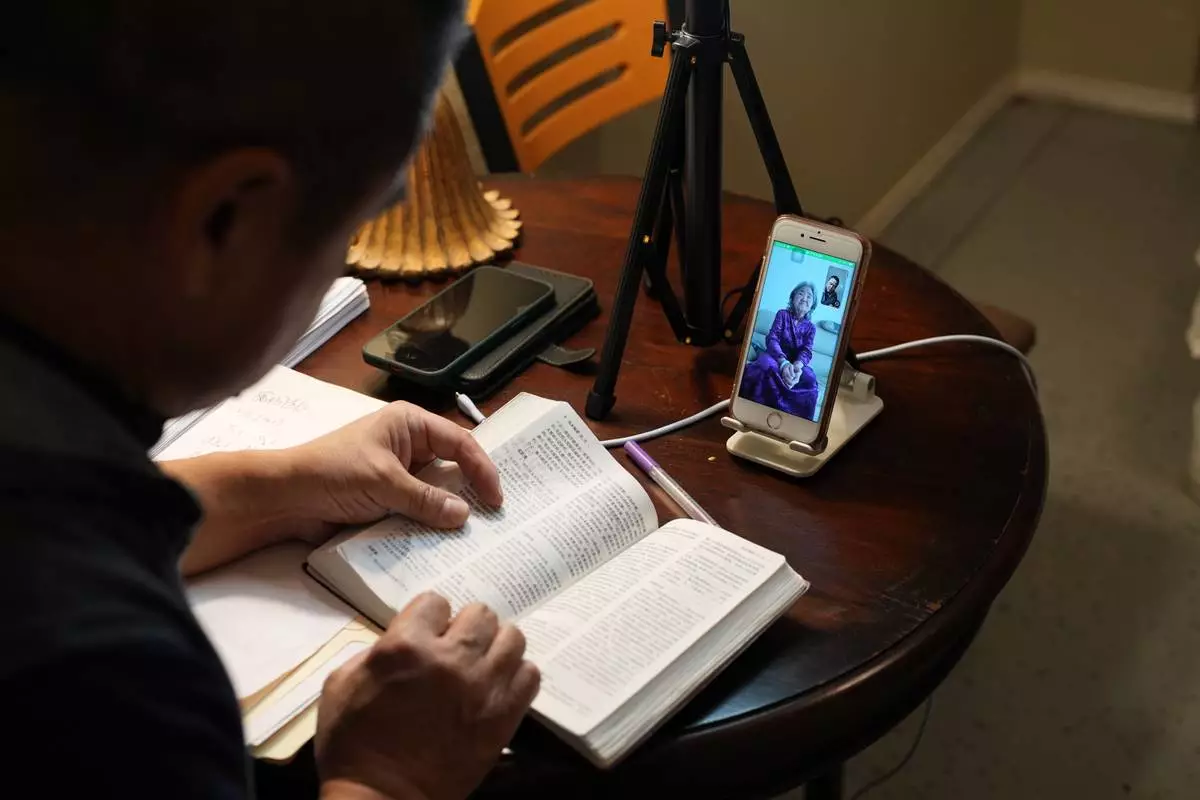

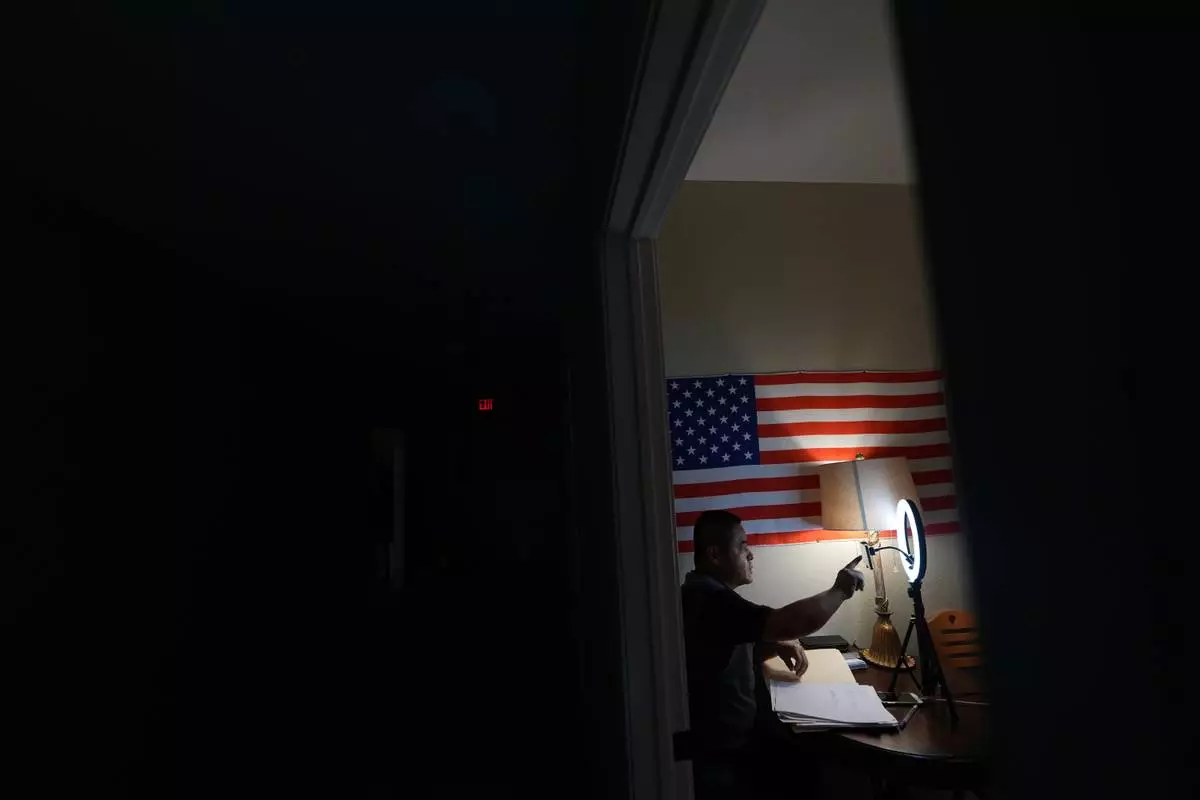

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang films a YouTube broadcast from the Mayflower Church community in Midland, Texas, Jan. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Deep in the Texas countryside, Li has now found refuge with members of a Chinese church living in exile after fleeing from China like Li.

Here, the Chihuahuan Desert unfurls as a stark, flat expanse of sand, punctured by phone poles and wind turbines. Tumbleweeds roll across roads, past ranches flying the Lone Star flag and pumpjacks extracting oil.

Li and members of the church are building a new life, thousands of miles from China. They cook, eat, and study together. They plant olive trees and design new homes for their budding community. On Sundays, they attend church, singing hymns and reading the Bible.

But even in the United States, Li worries he’s being watched. Strange men stalk him. Spies have looked for him. He carries multiple phones.

Surveillance technology powers China’s anti-corruption crackdown at home and abroad — a campaign critics say is used to stifle dissent and exact retribution on perceived enemies.

Beijing has accused Li of corruption totaling around $435 million, but Li says he’s being targeted for openly criticizing the Chinese Communist Party. He denies criminal charges of taking bribes and embezzling state funds.

Li exudes some of the authority he once wielded as vice mayor. But he’s traded his suit and tie for a jacket vest, the Chinese flag for America’s star-spangled banner, and his podium and phalanx of state journalists for a bright, white LED light and flimsy tripod in a sparse room behind a communal church kitchen.

From here, Li tapes videos for an online audience, fighting a war of words with the party he once swore loyalty to.

This is a documentary photo story curated by AP photo editors.

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang adjusts his cap as he walks inside the Mayflower Church community in Midland, Texas, Jan. 19, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang sits in his car as he drives between buildings in the Mayflower Church community, Jan. 18, 2025, in Midland, Texas. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang harvests greens from a vegetable garden inside the Mayflower Church community in Midland, Texas, Jan. 19, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Zhang Qimiao plays with Li Chuanliang's German shepherd, Hardy, as the sun sets in the Mayflower Church community in Midland, Texas, Jan. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Lights shine inside the Mayflower Church hall, where members of the community gather for religious study or to enjoy downtime, in Midland, Texas, Jan. 19, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Nong Yitan plays foosball with other Mayflower Church kids inside the community hall in Midland, Texas, Jan. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

A Mayflower Church member walks out of the community's main hall, used for religious education and recreation, in Midland, Texas, Jan. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

The son of Mayflower Church Deacon, Luo Changcheng, who wasn't feeling well, naps in the room he shares with his parents, in Midland, Texas, Jan. 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

A bird flies from a window sill inside the Mayflower Church community hall in Midland, Texas, Jan. 19, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Mayflower Church member Chen Jingjing holds her daughter, Mo Nika, as she surveys the landscape from the porch of the family's trailer in Midland, Texas, Jan. 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Siblings Mo Songhua, left, Mo Songen, center, and Mo Nika, right, from the Mayflower Church community watch, "Peppa Pig," to strengthen their English, inside their family's trailer in Midland, Texas, Jan. 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Mayflower Church Deacon Luo Changcheng, wearing a tag with the American name Peter, gets a fist bump from his boss, Eric Smith, as he works at a car wash in Midland, Texas, Jan. 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang shops for meat at a supermarket in Midland, Texas, Jan. 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang, left, shares a meal with other members of the Mayflower Church, a Christian community which fled religious persecution in China, and American pastors who have welcomed the refugees, in Midland, Texas, Jan. 19, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Members of the Mayflower Church, a Christian community which fled religious persecution in China, pray at a church in Midland, Texas, Jan. 19, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang holds a Bible as he prays inside the Mayflower Church temple sanctuary in Midland, Texas, Jan. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang shows one of the few pictures he has of himself, at right, from when he was vice mayor of Jixi, China, in the Mayflower Church community in Midland, Texas, Jan. 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Pumpjacks work to extract oil as the sun rises in Midland, Texas, Jan. 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang greets his German shepherd, Hardy, as he returns from a trip to town from the Mayflower Church community in Midland, Texas, Jan. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang reads the Bible to his elderly mother, Shen Shuzi, who is back in China, over a video call in Midland, Texas, Jan. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Former Chinese official Li Chuanliang films a YouTube broadcast from the Mayflower Church community in Midland, Texas, Jan. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

THE HAGUE, Netherlands (AP) — Judges and prosecutors at the International Criminal Court are trying to live and work under the same U.S. financial and travel restrictions brought against Russian President Vladimir Putin and Osama bin Laden.

Nine staff members, including six judges and the ICC's chief prosecutor, have been sanctioned by U.S. President Donald Trump for pursuing investigations into officials from the U.S. and Israel, which aren't among The Hague court's 125 member states.

Typically reserved for autocrats, crime bosses and the like, the sanctions can be devastating. They prevent the ICC officials and their families from entering the United States, block their access to even basic financial services and extend to the minutiae of their everyday lives.

The court's top prosecutor, British national Karim Khan, had his bank accounts closed and his U.S. visa revoked, and Microsoft even canceled his ICC email address. Canadian judge Kimberly Prost, who was named in the latest round of sanctions in August, immediately lost access to her credit cards, and Amazon's Alexa stopped responding to her.

“Your whole world is restricted,” Prost told The Associated Press last week.

Prost had an inkling of what would happen when she made the list. Before joining the ICC in 2017, she worked on sanctions for the U.N. Security Council. She was targeted by the Trump administration for voting to allow the court’s investigation into alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Afghanistan, including by American troops and intelligence operatives.

“I’ve worked all my life in criminal justice, and now I’m on a list with those implicated in terrorism and organized crime,” she said.

The sanctions have taken their toll on the court’s work across a broad array of investigations at a time when the institution is juggling ever more demands on its resources and a leadership crisis centered on Khan. Earlier this year, he stepped aside pending the outcome of an investigation into allegations of sexual misconduct. He denies the allegations.

How companies comply with sanctions can be unpredictable. Businesses and individuals risk substantial U.S. fines and prison time if they provide sanctioned people with “financial, material, or technological support,” forcing many to stop working with them.

The sanctions' effects can be sweeping and even surprising.

Shortly after she was listed, Prost bought an e-book, “The Queen’s Necklace” by Antál Szerb, only to later find it had disappeared from her device.

“It’s the uncertainty,” she said. “They are small annoyances, but they accumulate.”

Luz del Carmen Ibáñez Carranza, a sanctioned Peruvian judge who was involved in the same Afghanistan decision as Prost, told the AP that the problems are “not only for me, but also for my daughters,” who can no longer attend work conferences in the U.S.

Deputy prosecutor Nazhat Shameem Khan echoed her colleagues’ concerns, saying “You’re never quite sure when your card is not working somewhere, whether this is just a glitch or whether this is the sanction."

Meanwhile the staffers, some of whom also face arrest warrants in Russia, are worried that Washington might sanction the entire ICC, rendering it unable to pay employees, provide financial assistance to protected witnesses or even keep the lights on.

The ICC was established in 2002 as the world’s permanent court of last resort to prosecute individuals responsible for the most heinous atrocities — war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide and the crime of aggression. It only takes action when nations are unable or unwilling to prosecute those crimes on their territory.

The court has no police force and relies on member states to execute arrest warrants, making it very unlikely that any U.S. or Israeli official would end up in the dock. But those wanted by the court, like Putin, can risk arrest when traveling abroad or after leaving office — the ICC took custody this year of former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, who is accused of crimes against humanity for his deadly anti-drugs crackdowns.

When explaining Trump's executive order sanctioning the ICC in February, the White House said the move was in response to the “illegitimate and baseless actions targeting America and our close ally Israel."

"The United States will not tolerate efforts to violate our sovereignty or to wrongfully subject U.S. or Israeli persons to the ICC’s unjust jurisdiction," Tommy Pigott, a State Department spokesman, said in response to questions from the AP.

There is little the staff can do to get the sanctions lifted. Sanctions imposed during the first Trump administration against the previous prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, weren’t removed until Joe Biden became president.

Ibáñez, a former prosecutor in Peru, vowed that the sanctions wouldn't have any impact on her judicial activities in The Hague. “In my country, I prosecuted terrorists and drug lords. I will continue my work,” she said.

Prost, too, is defiant, saying the sanctioned staff “are absolutely undeterred and unfettered.”

FILE - Deputy Prosecutor Nazhat Shameem Khan attends a hearing at the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, Netherlands, Monday, Oct. 6, 2025. (Piroschka van de Wouw/Pool Photo via AP, file)

FILE - Presiding judge Luz del Carmen Ibanez Carranza prepares to rule on a request to release former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte at the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, Netherlands, Friday, Nov. 28, 2025. (Lina Selg/Pool Photo via AP, file)

An exterior view of the International Criminal Court, ICC, where Ali Muhammad Ali Abd al-Rahman, a leader of the Sudanese Janjaweed militia, will hear the court's verdict, in The Hague, Netherlands, Tuesday, Dec. 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)