The U.S. Justice Department is suing four more states as part of its effort to collect detailed voting data and other election information across the country.

The department filed federal lawsuits against Colorado, Hawaii, Massachusetts and Nevada on Thursday for "failing to produce statewide voter registration lists upon request." So far, 18 states have been sued, along with Fulton County in Georgia, which was sued for records related to the 2020 election.

The Trump administration has characterized the lawsuits as part of an effort to ensure the security of elections, and the Justice Department says the states are violating federal law by refusing to provide the voter lists and information about ineligible voters. The lawsuits have raised concerns among some Democratic officials and others who question exactly how the data will be used, and whether the department will follow privacy laws to protect the information. Some of the data sought includes names, dates of birth, residential addresses, driver's license numbers and partial Social Security numbers.

“States have the statutory duty to preserve and protect their constituents from vote dilution,” Assistant Attorney General Harmeet K. Dhillon of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division said in a press release. “At this Department of Justice, we will not permit states to jeopardize the integrity and effectiveness of elections by refusing to abide by our federal elections laws. If states will not fulfill their duty to protect the integrity of the ballot, we will.”

Colorado Secretary of State Jena Griswold, a Democrat, said her office declined to provide unredacted voter data.

“We will not hand over Coloradans’ sensitive voting information to Donald Trump. He does not have a legal right to the information,” Griswold said Thursday after the lawsuit was filed. “I will continue to protect our elections and democracy, and look forward to winning this case.”

In a Sept. 22 letter to the Justice Department, Hawaii Deputy Solicitor General Thomas Hughes said state law requires that all personal information required on a voter registration district other than a voter's full name, voting district or precinct and voter status, must be kept confidential. Hughes also said the federal law cited by the Justice Department doesn't require states to turn over electronic registration lists, nor does it require states to turn over “uniquely or highly sensitive personal information” about voters.

An Associated Press tally found that the Justice Department has asked at least 26 states for voter registration rolls in recent months, and in many cases asked states for information on how they maintain their voter rolls. Other states being sued by the Justice Department include California, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, New Mexico, Rhode Island, Vermont and Washington.

The bipartisan Wisconsin Elections Commission voted 5-1 on Thursday against turning over unredacted voter information to the Trump administration. The lone dissenter was Republican commissioner Robert Spindell, who warned that rejecting the request would invite a lawsuit. But other commissioners said it would be illegal under Wisconsin law to provide the voter roll information which includes the full names, dates of birth, residential addresses and driver’s license numbers of voters.

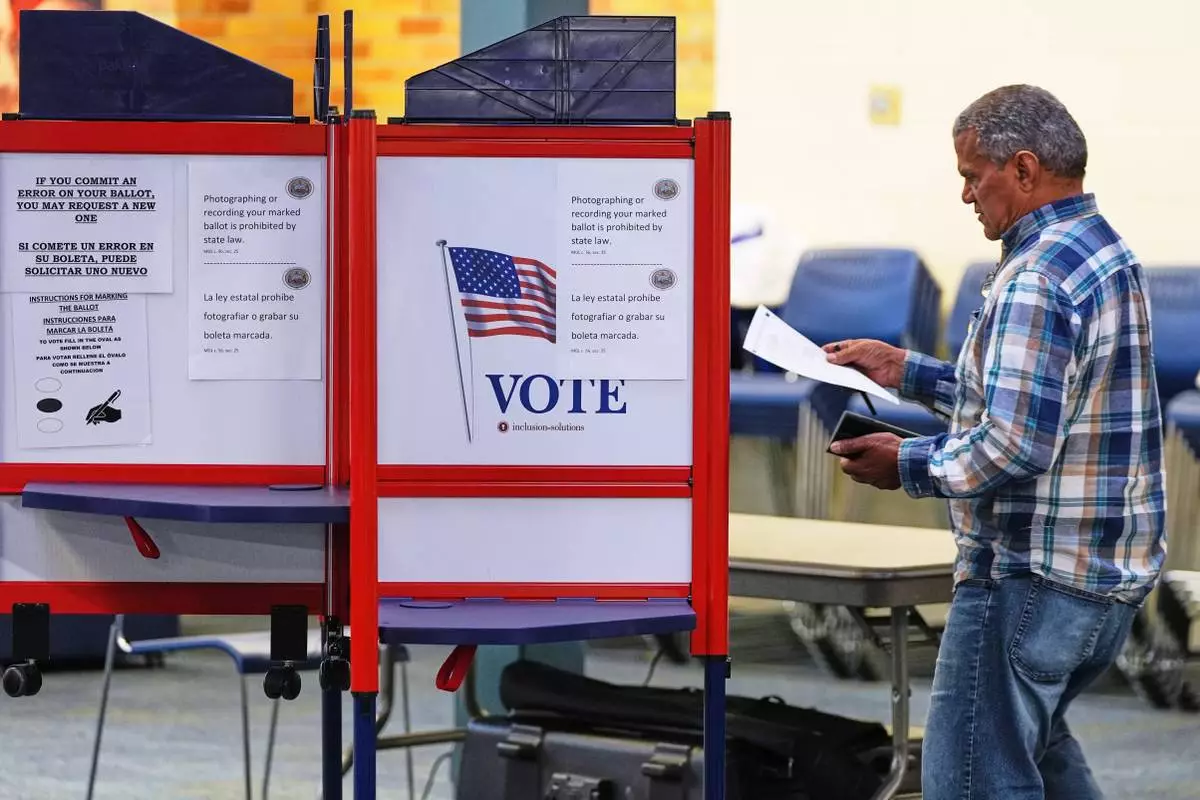

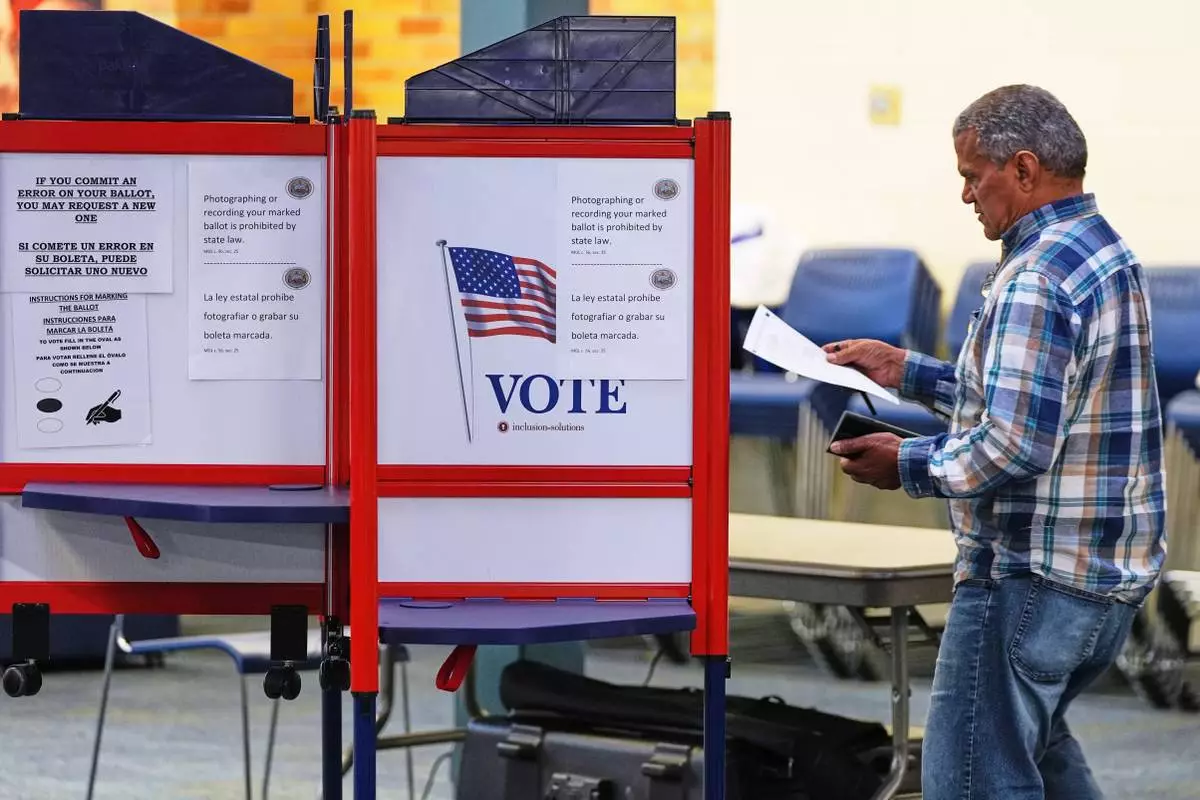

FILE - A voter carries his ballot to a booth at a polling station, Nov. 4, 2025, in Lawrence, Mass. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa, File)

NAPLES, Italy (AP) — At long last, vindication has arrived for an Oscar-winning composer who sought to prove he was just as capable of breathing life into Italy’s grand theaters as into gritty Hollywood films.

On Friday night, Naples’ Teatro San Carlo staged Ennio Morricone’s only opera, “Partenope,” three full decades after its composition. It is inspired by the mythical siren who drowned herself after failing to enchant Ulysses, her body washing ashore and becoming a settlement that grew over millennia into the seaside city of Naples.

When Morricone wrote “Partenope” in 1995, he was already the world-famous creator of the theme to the Spaghetti Western “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” and haunting soundtracks for epic films such as “The Untouchables” and “Once Upon a Time in America.”

He earned an Oscar for lifetime achievement in 2007, but his compositions never resounded in the hallowed halls of opera houses — viewed in his home country as the elite musical echelon. To his great chagrin, Partenope gathered dust for decades; Morricone died without seeing it performed.

“In the end, he read as a sign of destiny the fact he would not make his debut in the opera world,” Alessandro De Rosa, a close collaborator who coauthored Morricone's autobiography, said in an interview. “I’m sure that if he were alive now, he would have taken the challenge and would have dialogued with the orchestra and the director, tirelessly, like a young kid.”

Director Vanessa Beecroft and conductor Riccardo Frizza had to find their way through the visionary work without the benefit of those notes.

“It would have been wonderful to be able to talk to Morricone about his musical choices … but we had to understand them from what he left us and tried to interpret them in the best way,” Frizza said.

For instance, he chose not to use violins in this orchestra, instead favoring flutes, harps and horns, which appear in Greek mythology, Frizza explained.

“Then you have the modern instruments, lots of percussion, with the Neapolitan sounds provided by tambourines and putipu’,” he added, referencing a friction drum used in local folk music.

Teatro San Carlo was filled with anticipation on Thursday evening as Neapolitans attended an open rehearsal. Free tickets were snapped up in just a few hours.

“It was such a long wait, that’s why we are here today,” said Alfonso Ieneroso as he entered the theater.

The mythical Partenope is part of Naples’ culture, with tradition suggesting her voice represents the city’s enduring spirit. The original Greek settlement was named for her. She is depicted at monuments like the Fontana della Sirena, a fountain that has become one of the city's symbols. Young children all along the Gulf of Naples, living under Mount Vesuvius’ shadow, learn the legend of Partenope from their parents.

And like Morricone's opera, Naples itself spent decades downtrodden and overlooked, but is enjoying resurgence: The U.N. recognized its pizza makers as an intangible cultural heritage of humanity; It featured on foreign media lists of must-visit destinations; Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels were acclaimed bestsellers that became an HBO series; and its soccer team in 2023 took home the nation’s top league trophy for the first time since Maradona played in the 1980s — then won again in May.

Naples has also been celebrating its 2,500th anniversary this year, and Morricone’s opera marks the culmination of festivities. The protagonist in his adaptation is a woman who, after her husband dies and she is separated from her best friend, refuses the consolation of being transformed into a distant constellation. Instead, she asks the gods to let her stretch her wings along the gulf on which an immortal city will arise.

The production explores the link between the ancient legend and the modern city’s identity, as two sopranos embody Partenope simultaneously, reflecting her dual nature as body and myth.

Morricone originally composed the one-act opera — free of charge — to accompany a libretto by authors Guido Barbieri and Sandro Cappelletto for a small festival in Positano, just south of Naples on the Amalfi coast. But it was not to be: the festival went bankrupt and Partenope was shelved.

There were several attempts to revive their work, including one between 1998 and 2000 with the Teatro Massimo of Palermo. But that project ultimately ran aground when a director couldn’t be secured.

“In those years Morricone had the torment of not being accepted as a composer of what he called ‘absolute music,’ as he was identified with his popular movie scores,” Barbieri, one of the libretto’s authors, said in an interview. Cappelletto said that, in a conversation with the two authors in 2017, three years before his death, Morricone appeared “at peace” with his music career.

Partenope has inspired several productions over the centuries, including operas by renowned composers George Frideric Handel and Antonio Vivaldi in the 18th century, and a 2024 movie by Oscar-winning director Paolo Sorrentino. Morricone’s work is finally coming alive to join their ranks.

“It was a great pleasure to listen to Morricone’s music, the real protagonist of this opera,” said Giovanni Capuano, a 26-year-old cinema student, after Thursday's rehearsal. “His spirit is back and has enchanted us.”

Zampano reported from Rome.

People queue at the San Carlo Theatre, in Naples, Italy, to attend at the general rehearsal of Ennio Morricone's only opera, Partenope, Thursday, Dec. 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Salvatore Laporta)

Actors perform during the general rehearsal of Ennio Morricone's only opera, Partenope, at the San Carlo Theatre, in Naples, Italy, Thursday, Dec. 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Salvatore Laporta)

Actors perform during the general rehearsal of Ennio Morricone's only opera, Partenope, at the San Carlo Theatre, in Naples, Italy, Thursday, Dec. 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Salvatore Laporta)

EDS NOTE: NUDITY - Actors perform during the general rehearsal of Ennio Morricone's only opera, Partenope, at the San Carlo Theatre, in Naples, Italy, Thursday, Dec. 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Salvatore Laporta)

Actors perform during the general rehearsal of Ennio Morricone's only opera, Partenope, at the San Carlo Theatre, in Naples, Italy, Thursday, Dec. 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Salvatore Laporta)