LONDON (AP) — In the past year, tens of thousands hostile to immigrants marched through London, chanting “send them home!” A British lawmaker complained of seeing too many non-white faces on TV. And senior politicians advocated the deportation of longtime U.K. residents born abroad.

The overt demonization of immigrants and those with immigrant roots is intensifying in the U.K. — and across Europe — as migration shoots up the political agenda and right-wing parties gain popularity.

Click to Gallery

FILE - The leader of France's National Rally (RN) Jordan Bardella arrives as he attends at the French far-right party national rally near the parliament in support of Marine Le Pen in Paris, Sunday, April 6, 2025. (AP Photo/Michel Euler, File)

FILE - Stickers are offered at the re-founding of the AfD youth organization in Giessen, Germany, early Saturday, Nov. 29, 2025. (AP Photo/Martin Meissner, File)

FILE - People demonstrate during the Tommy Robinson-led Unite the Kingdom march and rally, in London, Saturday Sept. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Joanna Chan, File)

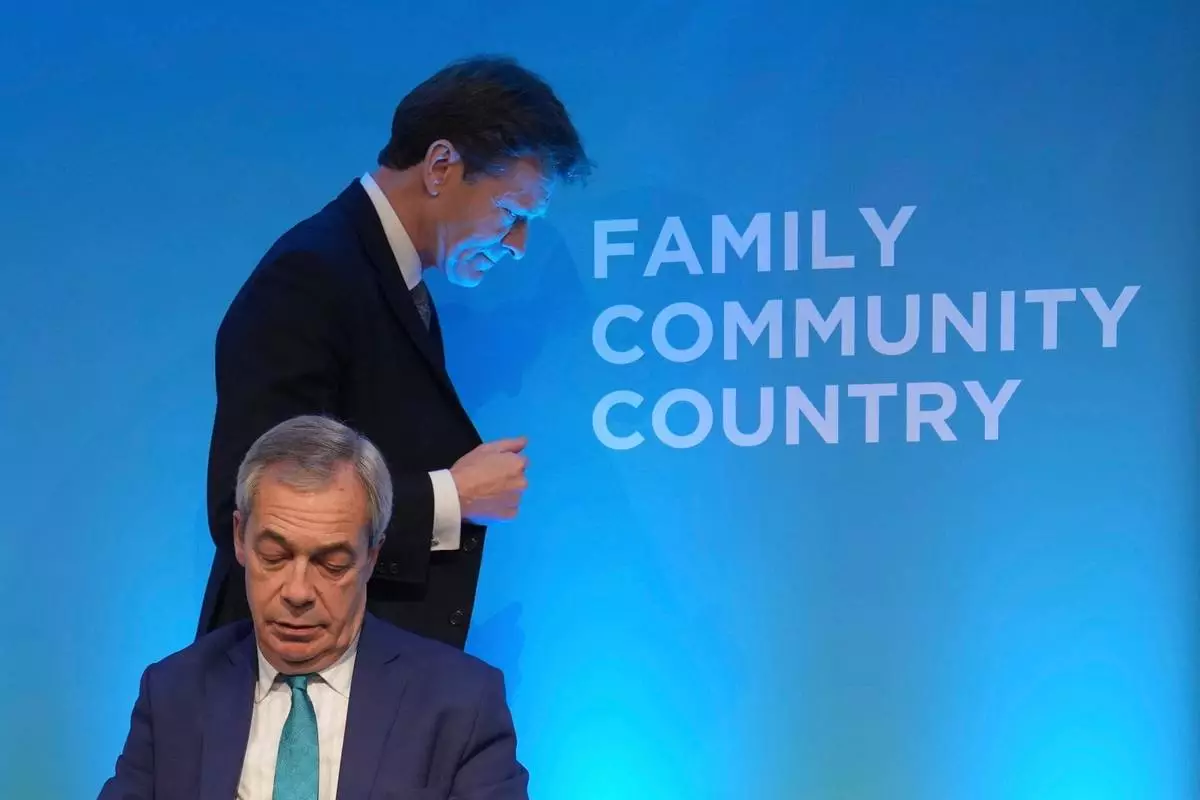

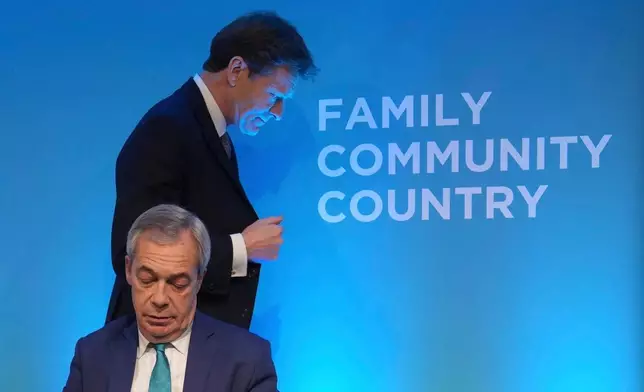

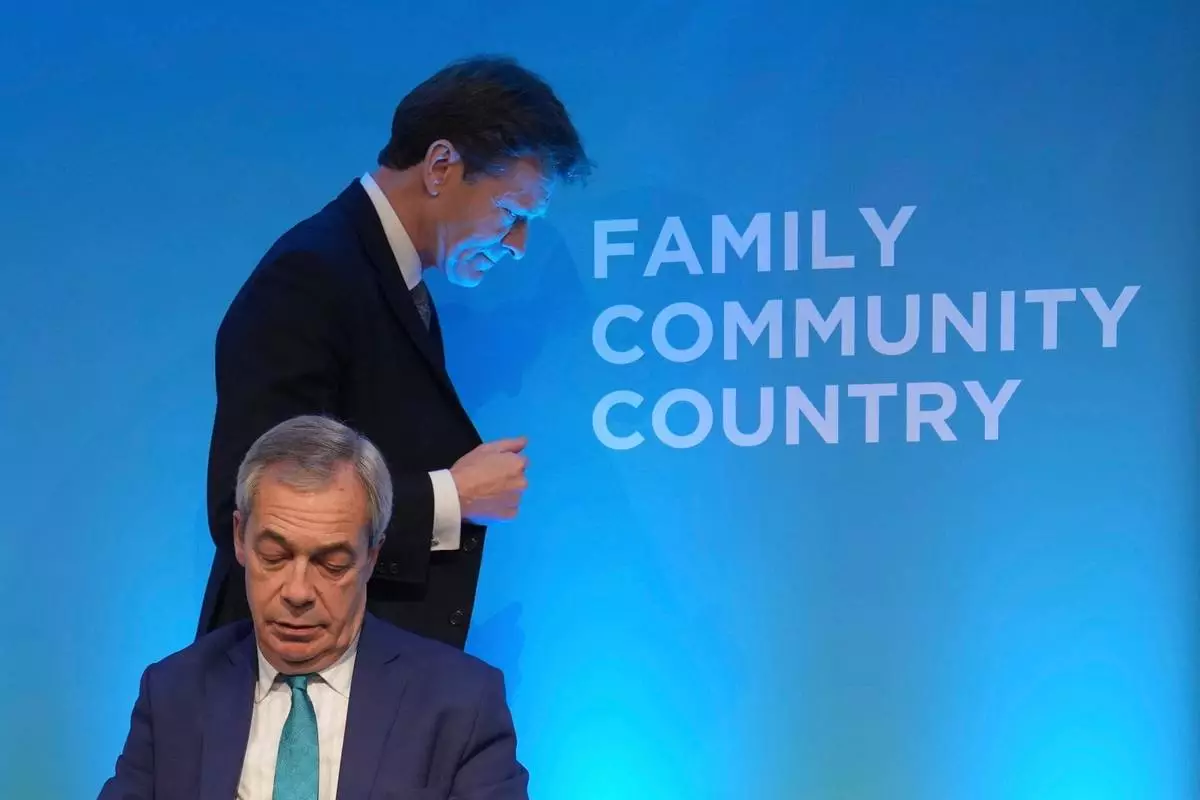

FILE - Reform UK leader Nigel Farage, front, and deputy leader Richard Tice attend a news conference on the economy and renewable energy, in London, Wednesday, Feb. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung, File)

FILE - Protesters wave a Union Flag during a demonstration in Orpington near London, Friday, Aug. 22, 2025 as the dilemma of how to house asylum-seekers in Britain got more challenging for the government after a landmark court ruling this week motivated opponents to fight hotels used as accommodation. (AP Photo/Alberto Pezzali, File)

In several European countries, political parties that favor mass deportations and depict immigration as a threat to national identity come at or near the top of opinion polls: Reform U.K., the AfD, or Alternative for Germany and France’s National Rally.

President Donald Trump, who recently called Somali immigrants in the U.S. “garbage” and whose national security strategy depicts European countries as threatened by immigration, appears to be endorsing and emboldening Europe's coarse, anti-immigrant sentiments.

Amid the rising tensions, Europe's mainstream parties are taking a harder line on migration and at times using divisive language about race.

“What were once dismissed as being at the far extreme end of far-right politics has now become a central part of the political debate,” said Kieran Connell, a lecturer in British history at Queen’s University Belfast.

Immigration has risen dramatically over the past decade in some European countries, driven in part by millions of asylum-seekers who have come to Europe fleeing conflicts in Africa, the Middle East and Ukraine.

Asylum-seekers account for a small percentage of total immigration, however, and experts say antipathy toward diversity and migration stems from a mix of factors. Economic stagnation in the years since the 2008 global financial crisis, the rise of charismatic nationalist politicians and the polarizing influence of social media all play a role, experts say.

In Britain, there is “a frightening increase in the sense of national division and decline” and that tends to push people toward political extremes, said Bobby Duffy, director of the Policy Unit at King’s College London. It took root after the financial crisis, was reinforced by Britain's debate about Brexit and deepened during the COVID-19 pandemic, Duffy said.

Social media has exacerbated the mood, notably on X, whose algorithm promotes divisive content and whose owner, Elon Musk, approvingly retweets far-right posts.

Across Europe, ethnonationalism has been promoted by right-wing parties such as Germany's AfD, France’s National Rally and the Fidesz party of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

Now it appears to have the stamp of approval from the Trump administration, whose new national security strategy depicts Europe as a collection of countries facing “economic decline” and “civilizational erasure” because of immigration and loss of national identities.

The hostile language alarmed many European politicians, but also echoed what they hear from their countries' far-right parties.

National Rally leader Jordan Bardella told the BBC he largely agreed with the Trump administration’s concern that mass immigration was “shaking the balance of European countries.”

Policies once considered extreme are now firmly on the political agenda. Reform UK, the hard-right party that consistently leads opinion polls, says if it wins power it will strip immigrants of permanent-resident status even if they have lived in the U.K. for decades. The center-right opposition Conservatives say they will deport British citizens with dual nationality who commit crimes.

A Reform UK lawmaker complained in October that advertisements were “full of Black people, full of Asian people.” Conservative justice spokesman Robert Jenrick remarked with concern that he “didn’t see another white face” in an area of Birmingham, Britain’s second-largest city. Neither politician had to resign.

Many proponents of reduced immigration say they are concerned about integration and community cohesion, not race. But that's not how it feels to those on the receiving end of racial abuse.

“There is no doubt it has worsened,” said Dawn Butler, a Black British lawmaker who says the vitriol she receives on social media “is increasing drastically, and has escalated into death threats.”

U.K. government statistics show police in England and Wales recorded more than 115,000 hate crimes in the year to March 2025, a 2% increase over the previous 12 months.

In July 2024, anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim violence erupted on Britain’s streets after three girls were stabbed to death at a Taylor Swift-themed dance class. Authorities said online misinformation wrongly identifying the U.K.-born teenage attacker as a Muslim migrant played a part.

In Ireland and in the Netherlands, protesters often demonstrate outside municipal meetings in communities where a new asylum center is proposed. Some protests have turned violent, with opponents of asylum-seekers throwing fireworks at riot police.

Across Europe, the main focus of protests has been hotels and other housing for asylum-seekers, which some say become magnets for crime and bad behavior. But the agenda of protest organizers is often much wider.

In September, more than 100,000 people chanting “We want our country back” marched through London in a protest organized by a far-right activist and convicted fraudster Tommy Robinson. Among the speakers was French far-right politician Eric Zemmour, who told the crowd that France and the U.K. both faced “the great replacement of our European people by peoples coming from the south and of Muslim culture.”

Mainstream European politicians condemn the “great replacement” conspiracy theory. Britain’s center-left Labour Party government has denounced racism and says migration is an important part of Britain’s national story.

At the same time, it is taking a tougher line on immigration, announcing policies to make it harder for migrants to settle permanently. The government says it is inspired by Denmark, which has seen asylum applications plummet since it started giving refugees only short-term residence.

Denmark and Britain are among a group of European countries pushing to weaken legal protections for migrants and make deportations easier.

Human rights advocates argue that attempts to appease the right just lead to ever-more-extreme policies.

“For every inch yielded, there’s going to be another inch demanded,” Council of Europe human rights commissioner Michael O’Flaherty told The Guardian. “Where does it stop? For example, the focus right now is on migrants, in large part. But who is it going to be about next time around?”

Politicians of the political center also have been criticized for adopting the language of the far right. British Prime Minister Keir Starmer said in May that Britain risked becoming an “island of strangers,” a phrase that echoed a notorious 1968 anti-immigration speech by the politician Enoch Powell. Starmer later said he had been unaware of the echo and regretted using the phrase.

Germany’s center-right Chancellor Friedrich Merz has hardened his language on migrants as the Alternative for Germany has grown more powerful. Merz caused an uproar in October by saying Germany had a problem with its “Stadtbild,” a word that translates as “city image” or cityscape. Critics felt Merz was implying that people who don’t look German don’t truly belong.

Merz later stressed that “we need immigration,” without which certain sectors of the economy, including health care, would cease to function.

Duffy said politicians should be responsible and consider how their rhetoric shapes public attitudes — though he added that's “quite a forlorn hope.”

"The perception that this divisiveness works has taken hold,” he said.

An earlier version of this story gave an incorrect name for the Alternative for Germany party.

Associated Press writers Mike Corder in The Hague, John Leicester in Paris, Suman Naishadham in Madrid, Sam McNeil in Brussels and Kirsten Grieshaber in Berlin contributed to this story.

FILE - The leader of France's National Rally (RN) Jordan Bardella arrives as he attends at the French far-right party national rally near the parliament in support of Marine Le Pen in Paris, Sunday, April 6, 2025. (AP Photo/Michel Euler, File)

FILE - Stickers are offered at the re-founding of the AfD youth organization in Giessen, Germany, early Saturday, Nov. 29, 2025. (AP Photo/Martin Meissner, File)

FILE - People demonstrate during the Tommy Robinson-led Unite the Kingdom march and rally, in London, Saturday Sept. 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Joanna Chan, File)

FILE - Reform UK leader Nigel Farage, front, and deputy leader Richard Tice attend a news conference on the economy and renewable energy, in London, Wednesday, Feb. 12, 2025. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung, File)

FILE - Protesters wave a Union Flag during a demonstration in Orpington near London, Friday, Aug. 22, 2025 as the dilemma of how to house asylum-seekers in Britain got more challenging for the government after a landmark court ruling this week motivated opponents to fight hotels used as accommodation. (AP Photo/Alberto Pezzali, File)

DOUANKARA, Mauritania (AP) — The girl lay in a makeshift health clinic, her eyes glazed over and her mouth open, flies resting on her lips. Her chest barely moved. Drops of fevered sweat trickled down her forehead as medical workers hurried around her, attaching an IV drip.

It was the last moment to save her life, said Bethsabee Djoman Elidje, the women's health manager, who led the clinic's effort as the heart monitor beeped rapidly. The girl had an infection after a sexual assault, Elidje said, and had been in shock, untreated, for days.

Her family said the 14-year-old had been raped by Russian fighters who burst into their tent in Mali two weeks earlier. The Russians were members of Africa Corps, a new military unit under Russia's defense ministry that replaced the Wagner mercenary group six months ago.

Men, women and children have been sexually assaulted by all sides during Mali's decade-long conflict, the U.N. and aid workers say, with reports of gang rape and sexual slavery. But the real toll is hidden by a veil of shame that makes it difficult for women from conservative, patriarchal societies to seek help.

The silence that nearly killed the 14-year-old also hurts efforts to hold perpetrators accountable.

The AP learned of the alleged rape and four other alleged cases of sexual violence blamed on Africa Corps fighters, commonly described by Malians as the “white men,” while interviewing dozens of refugees at the border about other abuses such as beheadings and abductions.

Other combatants in Mali have been blamed for sexual assaults. The head of a women’s health clinic in the Mopti area told the AP it had treated 28 women in the last six months who said they had been assaulted by militants with the al-Qaida affiliated JNIM, the most powerful armed group in Mali.

The silence among Malian refugees has been striking.

In eastern Congo, which for decades has faced violence from dozens of armed groups, “we didn’t have to look for people,” said Mirjam Molenaar, the medical team leader in the border area for Doctors Without Borders, or MSF, who was stationed there last year. The women "came in huge numbers.”

It's different here, she said: “People undergo these things and they live with it, and it shows in post-traumatic stress."

The aunt of the 14-year-old girl said the Africa Corps fighters marched everyone outside at gunpoint. The family couldn't understand what they wanted. The men made them watch as they tied up the girl’s uncle and cut off his head.

Then two of the men took the 14-year-old into the tent as she tried to defend herself, and raped her. The family waited outside, unable to move.

“We were so scared that we were not even able to scream anymore,” the aunt recalled, as her mother sobbed quietly next to her. She, like other women, spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation, and the AP does not name victims of rape unless they agree to be named.

The girl emerged over a half-hour later, looking terrified. Then she saw her uncle's body and screamed. She fainted. When she woke up, she had the eyes of someone “who was no longer there,” the aunt said.

The next morning, JNIM militants came and ordered the family to leave. They piled onto a donkey cart and set off toward the border. At any sound, they hid in the bushes, holding their breath.

The girl's condition deteriorated during the three-day journey. When they arrived in Mauritania, she collapsed.

The AP came across her lying on the ground in the courtyard of a local family. Her family said they had not taken her to a clinic because they had no money.

“If you have nothing, how can you bring someone to a doctor?” the girl’s grandmother said between sobs. The AP took the family to a free clinic run by MSF. A doctor said the girl had signs of being raped.

The clinic had been functioning for barely a month and had seen three survivors of sexual violence, manager Elidje said.

“We are convinced that there are many cases like this," she said. "But so far, very few patients come forward to seek treatment because it’s still a taboo subject here. It really takes time and patience for these women to open up and confide in someone so they can receive care. They only come when things have already become complicated, like the case we saw today.”

As Elidje tried to save the girl's life, she asked the family to describe the incident. She did not speak Arabic and asked the local nurse to find out how many men carried out the assault. But the nurse was too ashamed to ask.

Thousands of new refugees from Mali, mostly women and children, have settled just inside Mauritania in recent weeks, in shelters made of fabric and branches. The nearest refugee camp is full, complicating efforts to treat and report sexual assaults.

Two recently arrived women discreetly pulled AP journalists aside, adjusting scarves over their faces. They said they had arrived a week ago after armed white men came to their village.

“They took everything from us. They burned our houses. They killed our husbands,” one said. “But that’s not all they did. They tried to rape us.”

The men entered the house where she was by herself and undressed her, she said, adding that she defended herself “by the grace of Allah.”

As she spoke, the second woman started crying and trembling. She had scratch marks on her neck. She was not capable of telling her story.

“We are still terrified by what we went through,” she said.

Separately, a third woman said that what the white men did to her in Mali last month when she was alone at home “stays between God and me.”

A fourth said she watched several armed white men drag her 18-year-old daughter into their house. She fled and has not seen her daughter again.

The women declined the suggestion to speak with aid workers, some of whom are locals. They said they were not ready to talk about it with anyone else.

Russia’s Defense Ministry did not respond to questions, but an information agency that the U.S. State Department has called part of the “Kremlin’s disinformation campaign” called the AP’s investigation into Africa Corps fake news.

Allegations of rapes and other sexual assaults were already occurring before Wagner transformed into Africa Corps.

One refugee told the AP she witnessed a mass rape in her village in March 2024.

“The Wagner group burned seven men alive in front of us with gasoline.” she said. Then they gathered the women and raped them, she said, including her 70-year-old mother.

“After my mother was raped, she couldn’t bear to live,” she said. Her mother died a month later.

In the worst-known case of sexual assault involving Russian fighters in Africa, the U.N. in a 2023 report said at least 58 women and girls had been raped or sexually assaulted in an attack on Moura village by Malian troops and others that witnesses described as “armed white men."

In response, Mali’s government expelled the U.N. peacekeeping mission. Since then, gathering accurate data on the ground about conflict-related sexual violence has become nearly impossible.

The AP interviewed five of the women from Moura, who now stay in a displacement camp. They said they had been blindfolded and raped for hours by several men.

Three of the women said they hadn't spoken about it to anyone apart from aid workers. The other two dared to tell their husbands, months later.

“I kept silent with my family for fear of being rejected or looked at differently. It’s shameful,” one said.

The 14-year-old whose family fled to Mauritania is recovering. She said she cannot remember anything since the attack. Her family and MSF said she is speaking to a psychiatrist — one of just six working in the country.

Aid workers are worried about others who never say a thing.

“It seems that conflict over the years gets worse and worse and worse. There is less regard for human life, whether it’s men, women or children,” said MSF’s Molenaar, and broke into tears. “It’s a battle.”

For more on Africa and development: https://apnews.com/hub/africa-pulse

The Associated Press receives financial support for global health and development coverage in Africa from the Gates Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content. Find the AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Relatives of a young Malian woman being treated for her dangerously high fever and infection by doctors at the Douankaran health clinic leave the hospital in the Hodh El Chargui Region, Mauritania, Nov. 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)

Doctors pick up medicine in the pharmacy of the Douankaran health clinic in the Hodh El Chargui Region, Mauritania, Nov. 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)

A Malian woman, whose 14-year-old niece was abused by Africa Corps Russian mercenaries in Mali, waits outside the Bassikounou hospital where her niece is being treated in the Hodh El Chargui Region, where they found refuge, in Mauritania, Nov. 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)

Malian refugees fleeing violence in Mali, sit in a makeshift camp where they found refuge in Douankara, Hodh El Chargui Region, Mauritania, Nov. 9 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)

A young Malian woman is treated for her dangerously high fever and infection by doctors at the Douankaran health clinic in the Hodh El Chargui Region, Mauritania, Nov. 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)