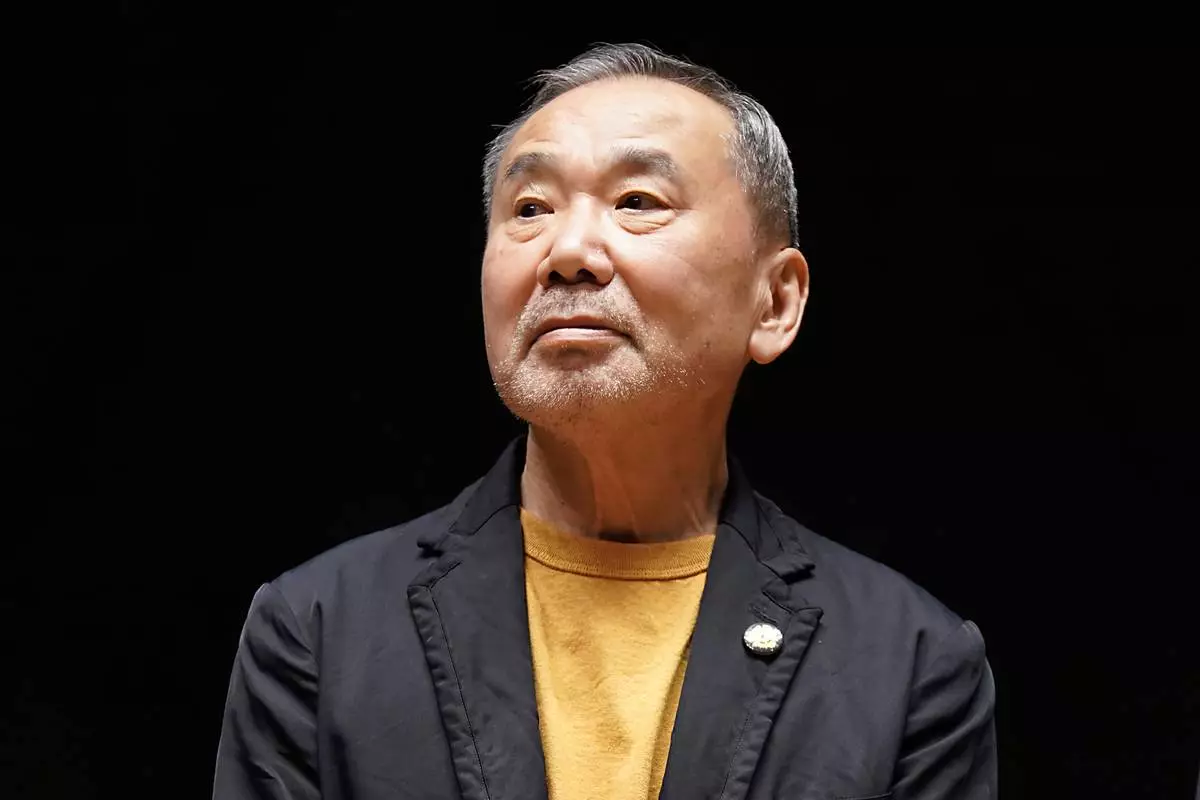

NEW YORK (AP) — Haruki Murakami was in town last week to hear his words set to music and his praises literally sung.

The 76-year-old Tokyo resident and perennial Nobel Prize candidate received a pair of honors in Manhattan for his long career as a storyteller, translator, critic and essayist. On Tuesday night, the Center for Fiction presented him its Lifetime of Excellence in Fiction Award, previously given to Nobel laureates Toni Morrison and Kazuo Ishiguro among others. Two days later, the Japan Society co-hosted a jazzy tribute at The Town Hall, “Murakami Mixtape,” and awarded him its annual prize for “luminous individuals (including Yoko Ono and Caroline Kennedy ) who have brought the U.S. and Japan closer together.”

Murakami fans know him for such novels as “Kafka on the Shore” and “The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle,” and for his themes of identity, isolation and memory. But they also pick up on his non-literary passions, from beer and baseball to running and jazz. Praising him requires more work than it does for your average high-achieving writer.

At the Center for Fiction gala, held at the downtown Cipriani 25 Broadway, longtime Murakami admirer Patti Smith introduced the author with the ballad “Wing” and its lofty refrain, “And if there’s one thing/I could do for you/You’d be a wing/In heaven blue.” She then shared memories of first learning about him, holding up an old copy of his debut novel, “Hear the Wind Sing,” and reading its opening sentence: “There’s no such thing as perfect writing, just like there’s no such thing as perfect despair.”

Smith said, “I was hooked, immediately.”

The Town Hall “Mixtape” was a sold-out, bilingual evening of music, readings and reflections, framed by Murakami's opening and closing remarks and presided over by the prize-winning jazz pianist Jason Moran, translator-publisher Motoyuki Shibata and author-scholar Roland Nozomu Kelts. “Murakami Mixtape” was entertainment for the casual fan — author tributes don't often include a makeshift bar on stage — and educational even for the specialist, featuring Murakami works little known to English-language readers.

Kelts (reading in English) and Shibata (reading in Japanese) selected fiction and nonfiction passages for Moran and his accompanists to weave through and around. They read from the surreal “Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World” and the memoir “What I Talk About When I Talk About Running.” But they also highlighted such rarities as the short story “The 1963/1982 Girl from Ipanema,” in which the narrator shares a drink with the bossa nova muse, and an old essay about New York before Murakami had ever seen it.

“Does New York City really exist?” Murakami wondered. “I don’t believe, one hundred percent, the existence of the city. Ninety-nine percent, I would say. In other words, if someone came up to me and said, ‘You know, there’s actually no such thing as New York City,’ I wouldn’t be that surprised.”

Kelts remembered asking Murakami about some of his favorite international stops, and how his choices, including Boston and Stockholm, were home to used jazz stores worthy of repeated visits. Murakami's affair with jazz began in his teens, in 1963, when Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers were on tour in Japan. It was rekindled at The Town Hall when Moran brought out the last surviving member of that band, 88-year-old bassist Reggie Workman, who joined the other musicians for a jam on “Ugetsu” (the title track of a live Blakey album) and capped it with a searching solo.

Murakami appeared briefly at the end to read a portion in Japanese from “Kafka on the Shore,” and explained that he might have been a musician instead of a writer, but he couldn’t bear to rehearse every day. At the start of the evening, Murakami shared some impressions of New York once he did arrive, in 1991. His comments were read in English by Japan Society President & CEO Joshua Walker.

“Back then was the height of Japan bashing,” Murakami said. “You could find events, where, for a dollar, they hand you a hammer and let you take a whack at a Japanese car.”

On Dec. 7, 1991, the 50th anniversary of the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, Murakami was advised to stay at home “just in case there was any trouble.” The author began to feel more welcome after Japan's economy fell into a decades-long slump, the threat to the U.S. apparently diminished. But he continued to feel isolated by his native country's “cultural” deficit.

“You often hear that Japan has no real face, no identity. I almost never came across contemporary Japanese fiction in American bookstores. As a Japanese writer, I couldn’t help but feel a real sense of crisis,” he said.

“And now I see young Japanese writers venturing abroad, earning recognition, their books being picked up by readers as a matter of course, in music, film, anime and more. The advances have been remarkable. Economically, people talk about Japan’s three last decades, but culturally, I think it’s fair to say that Japan’s face has finally emerged.”

FILE - Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami appears during a press conference at the Waseda University in Tokyo on Sept. 22, 2021. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko, File)