NEW YORK (AP) — Christine Baranski was in the playground outside St. Matthew’s Church in Bedford, New York, about three years ago when she came across Matthew Guard, artistic director of the Grammy-nominated Skylark Vocal Ensemble.

“I love choral music,” she told him.

An Emmy- and Tony-Award winning actor, Baranski went on to attend some of his concerts.

“I was a fangirl basically,” she recalled. “And I think we just said, `Wouldn’t it be fun to do something together?’”

Baranski agreed to narrate a music-and-spoken word version of Charles Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol” last December at The Morgan Library & Museum in New York, which owns the original manuscript of the 1843 classic. A recording was made last June at the Church of the Redeemer in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, and released Dec. 4 on the LSO Live label.

She will perform it again with the group on Thursday night at the Morgan, which is displaying the manuscript through Jan. 11, and again the following night at The Breakers in Newport, Rhode Island, where she will again portray the acerbic Agnes van Rhijn when Season 4 of HBO’s “The Gilded Age” starts filming season four on Feb. 23.

“I have this thing about keeping language alive, keeping beautiful, well-written language,” she said. “Dickens, Stoppard, Shakespeare. We’re getting awfully lazy in our use of the English language.”

She compliments Julian Fellowes, creator of “The Gilded Age” and “Downton Abbey,” for distinguished prose.

“I think he’d play Agnes if he could,” she said. “He gives her the witty stuff.”

Baranski leaned on the skills that earned her an Emmy for “Cybill” and Tonys for “The Real Thing” and “Rumors.”

“You get to bring to life a lot of different characters, none the least of which is Ebenezer,” she said at the library this month. “It’s wonderful for an actor to differentiate in as subtle a way as possible these different characters. As an acting piece, it’s wonderful. And not many women have done it. It’s been done by Alistair Cooke and Patrick Stewart and Patrick Page and all these great actors — but I get to do it with a chorus.”

Guard weaves in underscoring by composer Benedict Sheehan with Baranski’s words and 10 carols that include “Silent Night” and “Deck the Halls” plus “Auld Lang Syne.”

Reciting the entire story would have created a Wagnerian-length evening.

“This manuscript itself is about 30,000 words and we needed about 5,000 to make it a concert length,” Guard said. “I tried to create space in the narrative for obvious musical exclamation points or emotional feelings, almost like arias in an opera.”

Sheehan had worked together with Guard on a 2020 recording “Once Upon a Time” that weaved together the Brothers Grimm’s “Snow White and the Seven Dwarves” and Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid.”

“I said why don’t you commission me to write choral underscoring for the narrative that can kind of stitch together these different choral pieces?” Sheehan said.

Baranski got narration experience in 2023 when she replaced Liev Schreiber with the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra at Carnegie Hall for Beethoven’s “Egmont.”

“I could do this the rest of my career,” she thought at the time. “Just put me in a concert hall surrounded by great musicians.”

After working with dialect coach Howard Samuelsohn, Baranski practiced on Zoom to hone a 19th-century voice and avoid cliché.

“I said this is a good warm up for Aunt Agnes because it’s that kind of speech we were taught at Juilliard,” the 73-year-old Baranski said, recalling lessons from Edith Skinner decades ago.

“Sometimes it’s just a question of modulating your voice, just different rhythms and staccato or legato,” she said. “I want the voice of the Ghost of Christmas past to be disembodied… ethereal.”

She didn’t have an urge to join in on the carols.

“We take from each other,” she said. “When the chorus first heard my version of it, I think it subtly influenced the feeling of it and I take from the mood of the carol and bring it into my interpretation.”

“It’s a really exciting back-and-forth actually,” Guard said. “It’s not really totally clear who’s driving the bus at times.”

Baranski hopes the project has a future.

“We want to film this someday in the Morgan,” she said. “Make this a yearly event at the Morgan, because here’s the manuscript and people. It’s just one of those things like Handel’s `Messiah’ or `The Nutcracker.’”

She’s going to gift the CD to her grandchildren, four boys ranging from ages 2 to 12. Among her previous holiday experiences was portraying Martha May Whovier in the 2000 movie “Dr. Seuss’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas.”

“They’re curiously not interested in my even being Martha May in `The Grinch,’” Baranski explained. “Their friends sometimes say: `That’s your grandmother.’ But I just want to be their grandma — do you know what I mean — and not somebody?”

Skylark Artistic Director Matthew Guard and Christine Baranski are interviewed beside "A Christmas Carol In Prose; Being a Ghost Story of Christmas" by Charles Dickens, Dec. 1843," at The Morgan Library & Museum, in New York, Monday, Dec. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

Skylark Artistic Director Matthew Guard and Christine Baranski are interviewed beside "A Christmas Carol In Prose; Being a Ghost Story of Christmas" by Charles Dickens, Dec. 1843," at The Morgan Library & Museum, in New York, Monday, Dec. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

Skylark Artistic Director Matthew Guard and Christine Baranski are interviewed beside "A Christmas Carol In Prose; Being a Ghost Story of Christmas" by Charles Dickens, Dec. 1843," at The Morgan Library & Museum, in New York, Monday, Dec. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Richard Drew)

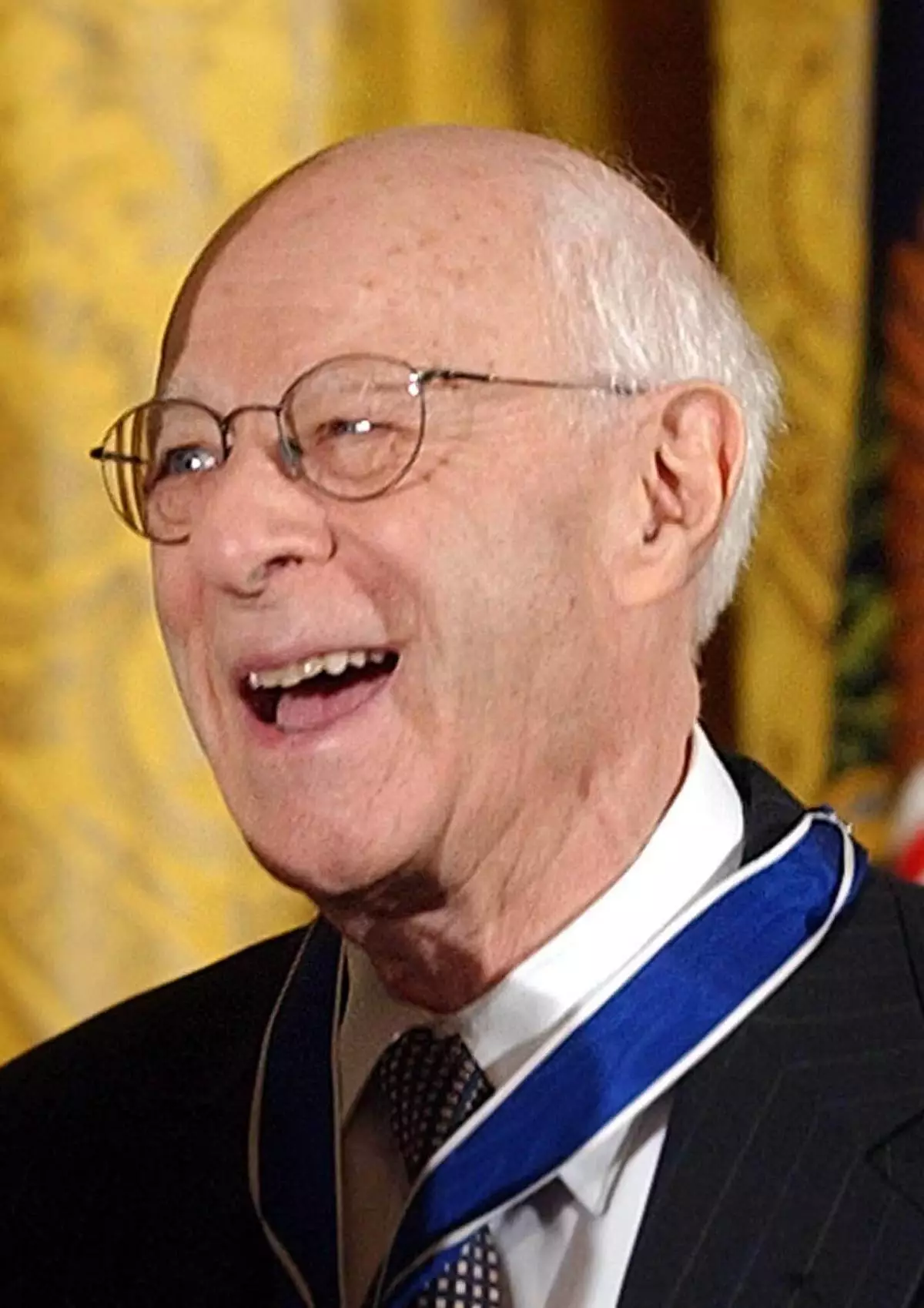

NEW YORK (AP) — Norman Podhoretz, the boastful, hard-line editor and author whose books, essays and stewardship of Commentary magazine marked a political and deeply personal break from the left and made him a leader of the neo-conservative movement, has died. He was 95.

Podhoretz died “peacefully and without pain” Tuesday night, his son John Podhoretz confirmed in a statement on Commentary's website. His cause of death was not immediately released.

“He was a man of great wit and a man of deep wisdom and he lived an astonishing and uniquely American life,” John Podhoretz said.

Norman Podhoretz was among the last of the so-called “New York intellectuals” of the mid-20th century, a famously contentious circle that at various times included Norman Mailer, Hannah Arendt, Susan Sontag and Lionel Trilling. As a young man, Podhoretz longed to join them. In middle age, he departed. Like Irving Kristol, Gertrude Himmelfarb and other founding neo-conservatives, Podhoretz began turning from the liberal politics he shared with so many peers and helped reshape the national dialogue in the 1960s and after.

The son of Jewish immigrants, Podhoretz was 30 when he was named editor-in-chief of Commentary in 1960, and years later transformed the once-liberal magazine into an essential forum for conservatives. Two future U.S. ambassadors to the United Nations, Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Jeane Kirkpatrick, received their appointments in part because of essays they published in Commentary that called for a more assertive foreign policy.

Despised by former allies, Podhoretz found new friends all the way to the White House, from President Ronald Reagan, a reader of Commentary; to President George W. Bush, who in 2004 awarded Podhoretz the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, and praised him as a "man of “fierce intellect” who never “tailored his opinion to please others.”

Podhoretz, who stepped down as editor-in-chief in 1995, had long welcomed argument. The titles of his books were often direct and provocative: "Making It," "The Present Danger," "World War IV," "Ex-Friends: Falling Out with Allen Ginsberg, Lionel and Diana Trilling, Lillian Hellman, Hannah Arendt, and Norman Mailer." He pressed for confrontation everywhere from El Salvador to Iran, and even disparaged Reagan for talking to Soviet leaders, calling such actions "the Reagan road to detente." For decades, he rejected criticism of Israel, once writing that “hostility toward Israel” is not only rooted in antisemitism but a betrayal of “the virtues and values of Western civilization.”

Meanwhile, Podhoretz became a choice target for disparagement and creative license. New York Times reviewer Michiko Kakutani called “World War IV” an “illogical screed based on cherry-picked facts and blustering assertions.” Ginsberg, once a fellow student at Columbia University, would mock the heavy-set editor for having “a great ridiculous fat-bellied mind which he pats too often.” Joseph Heller used Podhoretz as the model for the crass Maxwell Lieberman in his novel “Good as Gold.” Woody Allen cited Podhoretz's magazine in "Annie Hall," joking that Commentary and the leftist Dissent had merged and renamed themselves Dysentery.

Podhoretz never doubted he would be famous. Born and raised in a working class neighborhood in Brooklyn, he would credit the adoration of his family with giving him a sense of destiny. By his own account, Podhoretz was “the smartest kid in the class,” brash and competitive, a natural striver who believed that "One of the longest journeys in the world is the journey from Brooklyn to Manhattan."

He would indeed arrive in the great borough, and beyond, thriving as an English major at Columbia University, from which he graduated in 1950, and receiving a master's degree in England from Cambridge University. By his mid-20s, he was publishing reviews in all the best magazines, from The New Yorker to Partisan Review, and socializing with Mailer, Hellman and others.

He was named associate editor of Commentary in 1956, and given the top job four years later. Around the same time, he married the writer and editor Midge Decter, another future neo-conservative, and remained with her until her death in 2022.

In childhood, Norman Podhoretz’s world was so liberal that he later claimed he never met a Republican until high school. When Podhoretz took over Commentary, founded in 1945 by the American Jewish Committee, the magazine was a small, anti-Communist publication. Podhoretz's initial goal was to move it to the left — he serialized Paul Goodman's "Growing Up Absurd," published articles advocating unilateral disarmament — and make it more intellectual, with James Baldwin, Alfred Kazin and Irving Howe among the contributors. Subscriptions increased dramatically.

But signs of the conservative future also appeared, and of his own confusion over a world in transition. He was a prominent critic of Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and other Beat writers, dismissing the upstart movement in 1958 as a “revolt of the spiritually underprivileged” and branding Kerouac a “know-nothing." In a 1963 essay, Podhoretz admitted to being terrified of Black people as a child, agonized over "his own twisted feelings," wondered whether he, or anyone, could change and concluded that "the wholesale merging of the two races is the most desirable alternative for everyone concerned."

"Making It," released in 1967, was a final turning point. A blunt embrace of status seeking, the book was shunned and mocked by the audience Podhoretz cared about most: New York intellectuals. Podhoretz would look back on his early years and conclude that to advance in the world one had to make a “brutal bargain” with the upper classes, in part by acknowledging they were the upper classes. Friends urged him not to publish “Making It,” his agent wanted nothing to do with it and his original publisher, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, refused to promote it (Podhoretz gave back his advance and switched to Random House). Even worse, he was no longer welcome at literary parties, a deep wound for an author who had confessed that “at the precocious age of 35 I experienced an astonishing revelation: It is better to be a success than a failure."

By the end of the decade, Podhoretz was sympathizing less with the young leftists of the 1960s than with the way of life they were opposing. Like other neo-conservatives, he remained supportive of Democrats into the 1970s, but allied himself with more traditional politicians such as Edmund Muskie rather than the anti-Vietnam War candidate George McGovern. He would accuse the left of hostility to Israel and tolerance of antisemitism at home, with Gore Vidal (who called Podhoretz a “publicist for Israel”) a prime target. Echoing the opinions of Decter, he also rejected the feminist and gay rights movements as symptoms of a "plague" among "the kind of women who do not wish to be women and among those men who do not wish to be men."

“Tact is unknown to the Podhoretzes,” Vidal wrote of Podhoretz and Decter in 1986. “Joyously they revel in the politics of hate.”

Podhoretz was close to Moynihan, and he worked on the New York Democrat's successful Senate run in 1976, when in the primary Moynihan narrowly defeated the more liberal Bella Abzug. From 1981 to 1987, during the Reagan administration, Podhoretz served as an adviser to the United States Information Agency and helped write Kirkpatrick's widely quoted 1984 convention speech that chastised those who "blame America first." He was a foreign policy adviser for Republican Rudolph Giuliani's brief presidential run in 2008 and, late in life, broke again with onetime allies when he differed with other conservatives and backed Donald Trump.

“I began to be bothered by the hatred against Trump that was building up from my soon to be new set of ex-friends,” he told the Claremont Review of Books in 2019. “You could think he was unfit for office — I could understand that — but my ex-friends’ revulsion was always accompanied by attacks on the people who supported him. They called them dishonorable, or opportunists or cowards — and this was done by people like Bret Stephens, Bill Kristol, various others.

“And I took offense at that. So that inclined me to what I then became: anti-anti-Trump.”

FILE - Norman Podhoretz receives the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civil award, from President Bush during a ceremony in the East Room of the White House, June 23, 2004. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh, File)