MIAMI (AP) — Some oil vessels are diverting away from Venezuela after U.S. President Donald Trump threatened a “blockade” of sanctioned oil tankers entering or leaving the South American country, a dramatic escalation in the White House’s pressure campaign on leader Nicolás Maduro.

Trump said Tuesday on social media, in all caps, that he is ordering a "total and complete blockade of all sanctioned oil tankers” into and out of Venezuela, a move that threatens to choke off revenue from the world's largest oil reserves that are key to Maduro's grip on power.

It’s not clear exactly what Trump meant by his threats. U.S. sanctions adopted during his first administration make it illegal for Americans to purchase Venezuela’s crude oil without a license from the Treasury Department.

Additionally, hundreds of ships themselves have been sanctioned — part of a massive shadow fleet of often aging vessels that has proliferated in recent years to transport oil on behalf of Iran, Russia, Venezuela and other U.S. adversaries under sanctions.

At least 30 vessels under sanctions are navigating near Venezuela, according to Windward, a maritime intelligence firm that helps U.S. officials target the shadow fleet. A few have started to change their course, perhaps fearing they could face the same fate as the Skipper, a sanctioned vessel seized by U.S. forces last week near Venezuela.

“It’s quite clear that this has disrupted energy flows to and from Venezuela,” said Michelle Wiese Bockmann, a senior analyst at Windward. "Every hour when we’re tracking these vessels, we are seeing tankers that are deviating, loitering or changing their behavior.”

Among those is the Hyperion, which had been sailing toward the Jose port in Venezuela before doing a 90-degree turn early Wednesday and starting to head north away from the South American mainland.

The vessel, previously part of Russia’s state-owned shipping fleet, was one of 173 sanctioned in the final days of the Biden administration for allegedly facilitating Russian oil sales in violation of sanctions over Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine.

Following the penalties, the vessel changed its flag from the Comoros to Gambia. But the West African nation deleted Hyperion — along with dozens of other vessels — from its privately run ship registry in November for allegedly using false certificates claiming to have been issued by its maritime authority.

The vessel’s ownership also is obfuscated under multiple layers of offshore companies, some of them listed in Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

“It’s just screaming that it’s in a position to be seized,” Wiese Bockmann said.

Since the first Trump administration imposed punishing oil sanctions on Venezuela in 2017, Maduro’s government has boosted its reliance on a network of rogue tankers to smuggle a growing share of the roughly 900,000 barrels of oil per day that the OPEC nation produces.

Sanctioned tankers carried about 18% of Venezuela’s international shipments during the second half of this year, up from 6% in the first half of the year, according to Jim Burkhard, global head of oil markets and mobility at S&P Global Energy.

Burkhard said that while supplies to China, the main destination for most Venezuelan oil, could be affected, he doesn't expect any major disruption to oil markets.

“Volatility or uncertainty around Venezuela is not new, it’s not a shock,” he said. Markets also react more when supplies of oil are scarce, and “the market today is not tight. There’s plenty of oil.”

Unaffected for now is the roughly 143,000 barrels per day of Venezuelan heavy crude sent to U.S. refineries along the Gulf coast, much of it transported by Chevron, which has a waiver to operate in Venezuela.

“Chevron’s operations in Venezuela continue without disruption and in full compliance with laws and regulations applicable to its business, as well as the sanctions frameworks provided for by the U.S. government," spokesman Bill Turenne said.

Still, for the industry's rogue actors, Trump's threat of a blockade represents a paradigm shift.

“There are already ships that have decided not to leave Venezuela for fear of being seized, and there are also ships headed to Venezuela to load crude oil that decided to turn back," said Francisco Monaldi, a Venezuelan oil expert at Rice University in Houston.

That's good news for the oceans, where hundreds of vessels, many without insurance and poorly maintained, were a constant menace.

"Many of these are no more than floating rust buckets," said Wiese Bockmann, the Windward analyst. "So irrespective of the sanctions and the geopolitical reasons for their being targeted, it is a good thing to have a strategy to deal with them and to remove them from trading.”

Associated Press writer Michael Biesecker and Michelle L. Price in Washington, Regina Garcia Cano in Caracas, Venezuela, and David McHugh in Frankfurt, Germany, contributed to this report.

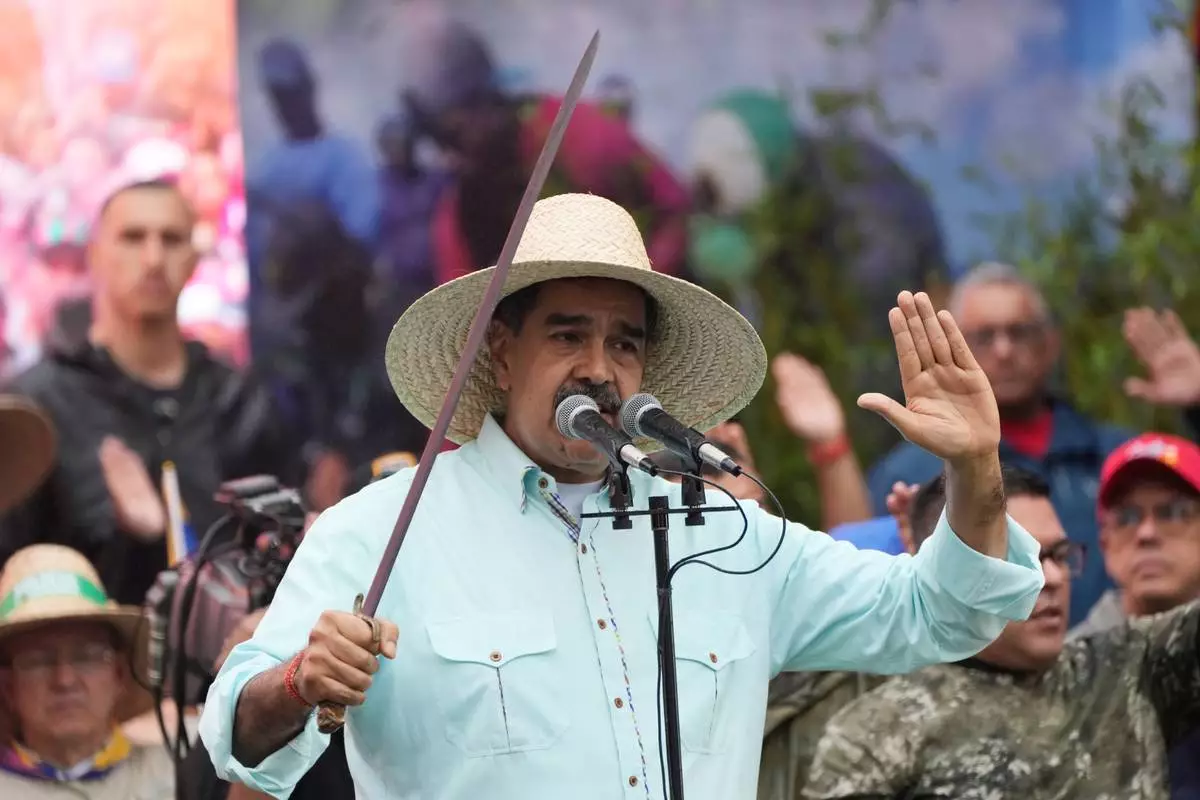

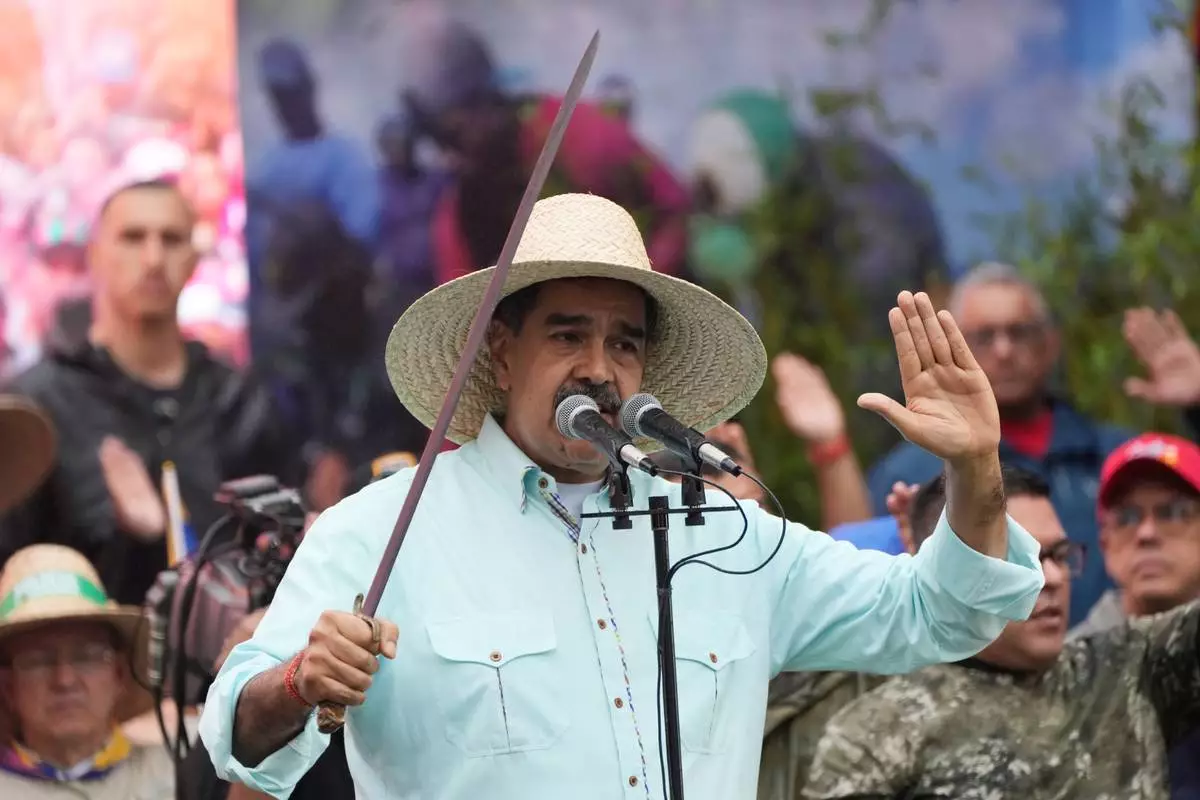

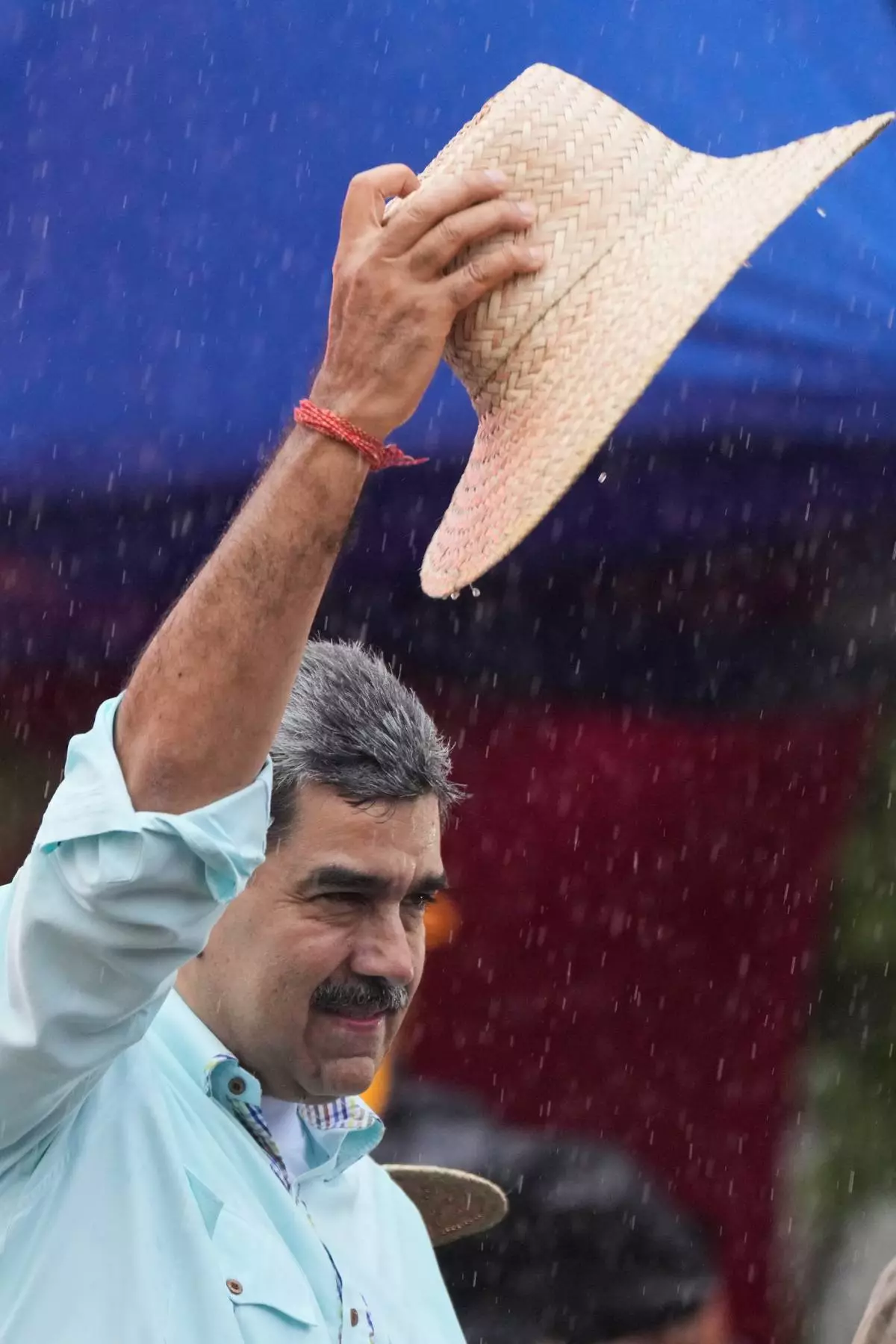

President Nicolas Maduro addresses supporters during a rally marking the anniversary of the Battle of Santa Ines, which took place during Venezuela's 19th-century Federal War, in Caracas, Venezuela, Wednesday, Dec. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)

CARACAS, Venezuela (AP) — U.S. President Donald Trump's threat to cut off Venezuelan oil sales could devastate a country already wrangling with years of spiraling crises.

The prospect added to Venezuelans' collective anxiety over their country's future on Wednesday. But after years of political, social and economic challenges, Venezuelans also treated the threat like another inconvenience — even when it could bring back the shortages of food, gasoline and other goods that defined the country last decade.

“Well, we’ve already had so many crises, shortages of so many things — food, gasoline — that one more ... well, one doesn’t worry anymore,” Milagro Viana said while waiting to catch a bus in Caracas, the capital.

Trump on Tuesday announced he was ordering a blockade of all “sanctioned oil tankers” into Venezuela, ramping up pressure on President Nicolás Maduro, who has been charged with narcoterrorism in the U.S. Trump’s escalation came after U.S. forces last week seized an oil tanker off Venezuela’s coast after a buildup of military forces in the region.

Venezuela has the world’s largest proven oil reserves and produces about 1 million barrels a day. The country's economy depends on the industry, with more than 80% of output exported.

Maduro’s government has relied on a shadowy fleet of unflagged tankers to smuggle crude into global supply chains since 2017, when the first Trump administration began imposing sanctions on Venezuela's oil industry.

In a post on social media announcing the blockade, Trump alleged that Venezuela was using oil to fund drug trafficking and other crimes. He vowed to continue the military buildup until Venezuela gives the U.S. oil, land and other assets. He wasn't specific about the basis for his claim.

David Smilde, a Tulane University professor who has studied Venezuela for more than three decades, said a full implementation of Trump’s threat will cause a huge economic contraction because oil represents 90% of the country’s exports.

“This is a country that traditionally imports a lot, not just finished goods, but most intermediate goods – everything from toilet paper to food containers,” Smilde said. “If you don’t have foreign currency coming up, that just brings the whole economy to a halt.”

That could lead to price increases as well as shortages of food and other basic goods. Fuel could also become scarce because some of the tankers ship Venezuela fluids that are used to produce gasoline for the local market.

“Things are going to get tough here,” Pedro Arangura said while he waited for a remittance store to open. “We have to put up with it. Nobody wants it, but it’s going to happen.”

Arangura said material difficulties could lead to Maduro’s ouster, echoing what Venezuela’s opposition has been telling supporters in recent months.

Nearby, Ismael Chirino, like Arangura, said he believes the population will “resist” whatever challenges result from Trump's latest move. But, Chirino said, people will do so to maintain Maduro in office.

“We held on. We didn’t have gas, we didn’t have gasoline, we didn’t have money, and yet, we withstood all of that,” Chirino said, referring to the second half of the 2010s, when the country's economy came undone and shortages were widespread. “I think they need to think very carefully if the U.S. wants to take over our wealth and all our territory."

The White House has said the military buildup, which began in the Caribbean and later expanded to the eastern Pacific Ocean, is meant to stop the flow of drugs into the U.S. The operation has killed more than 80 people, with Venezuelans among them.

Maduro denies the drug accusations. He and his allies have repeatedly said that the operation’s true purpose is to force a government change in Venezuela. They have also suggested that the U.S. is also after Venezuela's vast oil and mineral resources.

Smilde said Trump’s threat was a gift to Chavismo, the political movement that Maduro inherited from the late President Hugo Chávez, his predecessor and mentor. Chávez became president in 1999 with promises to uplift the poor and used an oil bonanza in the 2000s to push a self-described socialist agenda.

“There are few actions that any U.S. president has taken in the last 25 years that have better fit Chavismo’s line than Donald Trump’s tweet last night,” Smilde said. “They have been saying this from the beginning, ‘The U.S. wants our oil.’ So, finally, the discourse has the evidence.”

Follow AP’s coverage of Latin America and the Caribbean at https://apnews.com/hub/latin-america

People ride a boat along the coast in Macuto, Venezuela, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)

Residents and fisherman stand near Macuto beach in Venezuela, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)

Fresh tuna is for sale on Macuto beach in Venezuela, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)

A man looks out at the sea in the city of La Guaira, Venezuela, where the nation's flag flies, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)

A vendor sells inflatables on Macuto beach in Venezuela, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)

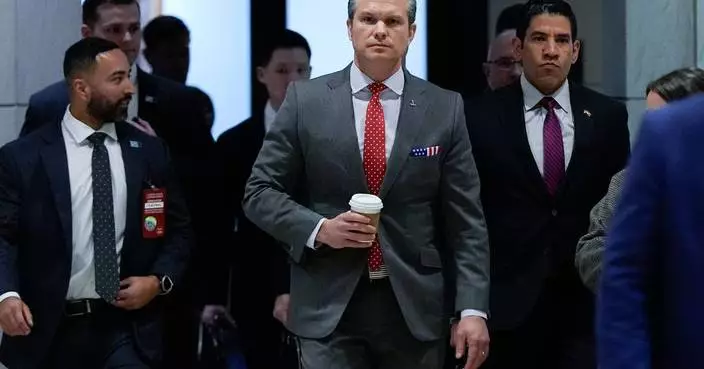

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth arrives to brief members of Congress on military strikes near Venezuela, Tuesday, Dec. 16, 2025, at the Capitol in Washington. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth departs the Capitol after briefing members of Congress on military strikes near Venezuela, Tuesday, Dec. 16, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

FILE - President Nicolas Maduro addresses supporters during a rally marking the anniversary of the Battle of Santa Ines, which took place during Venezuela's 19th-century Federal War, in Caracas, Venezuela, Wednesday, Dec. 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos, File)

A man looks out at the sea in the city of La Guaira, Venezuela, where the nation's flag flies, Wednesday, Dec. 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)