MILWAUKEE (AP) — A Wisconsin judge accused of helping a Mexican immigrant evade federal authorities is set to present her case as her trial on obstruction and concealment charges winds down.

Prosecutors rested their case against Milwaukee County Circuit Judge Hannah Dugan on Wednesday after three days of testimony. Dugan's defense attorneys said they planned to call four witnesses starting Thursday morning. It wasn’t clear whether Dugan would take the stand. Closing arguments could begin as early as Thursday afternoon.

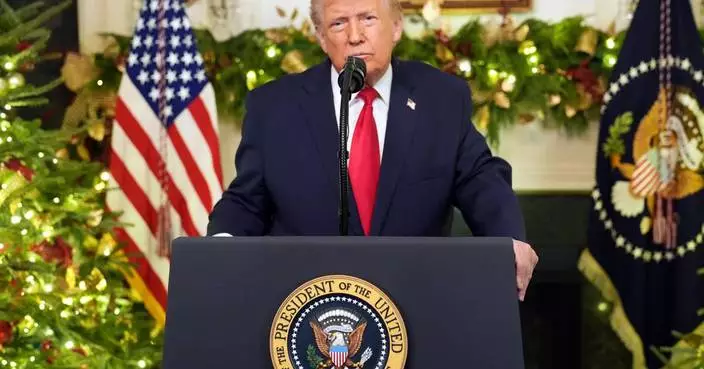

The highly unusual charges against a sitting judge are an extraordinary consequence of President Donald Trump’s immigration crackdown. Dugan’s supporters say Trump is looking to make an example of her to blunt judicial opposition to immigration arrests.

Prosecutors have tried to show that Dugan intentionally interfered with members of a federal immigration task force's efforts to arrest 31-year-old Eduardo Flores-Ruiz at the Milwaukee County Courthouse.

Members of the task force testified that they learned Flores-Ruiz was in the country illegally after he was arrested in Milwaukee on state battery charges. He was scheduled to appear for a hearing in front of Dugan on April 18. Six agents and officers staked out Dugan's courtroom that morning, ready to arrest him when he emerged from the hearing.

They testified that Dugan and another judge, Kristela Cervera, stepped into the hallway wearing their robes. Dugan angrily told four members of the team to report to the chief judge's office.

As Cervera led them to the office, Dugan went back to her courtroom and led Flores-Ruiz out a private door into the hallway. Prosecutors produced transcripts of audio recordings from microphones in her courtroom that show Dugan told her court reporter that she'd take “the heat” for showing Flores-Ruiz out the private door.

Two agents Dugan missed during her confrontations with the team followed Flores-Ruiz outside and a foot chase through traffic ensued before he was finally arrested. Members of the team testified that Dugan divided them and forced them out of position, leaving them too short-handed to make a safe arrest in the hallway.

Cervera, for her part, testified that she was uncomfortable backing up Dugan during her confrontations with the arrest team. She said she was shocked when she heard Dugan led Flores-Ruiz out a private door, adding that judges shouldn't help defendants evade arrest. Cervera also testified that Dugan told her three days after the incident that Dugan was “in the doghouse” with the chief judge, Carl Ashley, because she “tried to help that guy.”

Dugan's attorneys have countered during cross-examinations that Dugan didn't intend to obstruct the arrest team and was trying to follow a draft courthouse policy from Ashley that called for court employees to refer immigration agents looking to make an arrest in the courthouse to supervisors.

They've also argued that the arrest team could have apprehended Flores-Ruiz at any point after he emerged from the courtroom and Dugan shouldn't be blamed for their decision to wait until he got outside.

This courtroom sketch depicts Milwaukee County Circuit Judge Hannah Dugan in court, Tuesday, Dec. 16, 2025 in Milwaukee, Wis. (Adela Tesnow via AP)

MBERA, Mauritania (AP) — The men move in rhythm, swaying in line and beating the ground with spindly tree branches as the sun sets over the barren and hostile Mauritanian desert. The crack of the wood against dry grass lands in unison, a technique perfected by more than a decade of fighting bushfires.

There is no fire today but the men — volunteer firefighters backed by the U.N. refugee agency — keep on training.

In this region of West Africa, bushfires are deadly. They can break out in the blink of an eye and last for days. The impoverished, vast territory is shared by Mauritanians and more than 250,000 refugees from neighboring Mali, who rely on the scarce vegetation to feed their livestock.

For the refugee firefighters, battling the blazes is a way of giving back to the community that took them in when they fled violence and instability at home in Mali.

Hantam Ag Ahmedou was 11 years old when his family left Mali in 2012 to settle in the Mbera refugee camp in Mauritania, 48 kilometers (30 miles) from the Malian border. Like most refugees and locals, his family are herders and once in Mbera, they saw how quickly bushfires spread and how devastating they can be.

“We said to ourselves: There is this amazing generosity of the host community. These people share with us everything they have," he told The Associated Press. "We needed to do something to lessen the burden."

His father started organizing volunteer firefighters, at the time around 200 refugees. The Mauritanians had been fighting bushfires for decades, Ag Ahmedou said, but the Malian refugees brought know-how that gave them an advantage.

“You cannot stop bushfires with water,” Ag Ahmedou said. “That’s impossible, fires sometimes break out a hundred kilometers from the nearest water source."

Instead they use tree branches, he said, to smother the fire.

"That’s the only way to do it,” he said.

Since 2018, the firefighters have been under the patronage of the UNHCR. The European Union finances their training and equipment, as well as the clearing of firebreak strips to stop the fires from spreading. The volunteers today count over 360 refugees who work with the region's authorities and firefighters.

When a bushfire breaks out and the alert comes in, the firefighters jump into their pickup trucks and drive out. Once at the site of a fire, a 20-member team spreads out and starts pounding the ground at the edge of the blaze with acacia branches — a rare tree that has a high resistance to heat.

Usually, three other teams stand by in case the first team needs replacing.

Ag Ahmedou started going out with the firefighters when he was 13, carrying water and food supplies for the men. He helped put out his first fire when he was 18, and has since beaten hundreds of blazes.

He knows how dangerous the task is but he doesn't let the fear control him.

“Someone has to do it,” he said. "If the fire is not stopped, it can penetrate the refugee camp and the villages, kill animals, kill humans, and devastate the economy of the whole region.”

About 90% of Mauritania is covered by the Sahara Desert. Climate change has accelerated desertification and increased the pressure on natural resources, especially water, experts say. The United Nations says tensions between locals and refugees over grazing areas is a key threat to peace.

Tayyar Sukru Cansizoglu, the UNHCR chief in Mauritania, said that with the effects of climate change, even Mauritanians in the area cannot find enough grazing land for their own cows and goats — so a “single bushfire” becomes life-threatening for everyone.

When the first refugees arrived in 2012, authorities cleared a large chunk of land for the Mbera camp, which today has more than 150,000 Malian refugees. Another 150,000 live in villages scattered across the vast territory, sometimes outnumbering the locals 10 to one.

Chejna Abdallah, the mayor of the border town of Fassala, said because of “high pressure on natural resources, especially access to water,” tensions are rising between the locals and the Malians.

Abderrahmane Maiga, a 52-year-old member of the “Mbera Fire Brigade,” as the firefighters call themselves, presses soil around a young seedling and carefully pours water at its base.

To make up for the vegetation losses, the firefighters have started setting up tree and plant nurseries across the desert — including acacias. This year, they also planted the first lemon and mango trees.

“It’s only right that we stand up to help people,” Maiga said.

He recalls one of the worst fires he faced in 2014, which dozens of men — both refugees and host community members — spent 48 hours battling. By the time it was over, some of the volunteers had collapsed from exhaustion.

Ag Ahmedou said he was aware of the tensions, especially as violence in Mali intensifies and going back is not an option for most of the refugees.

He said this was the life he was born into — a life in the desert, a life of food scarcity and "degraded land" — and that there is nowhere else for him to go. Fighting for survival is the only option.

“We cannot go to Europe and abandon our home," he said. "So we have to resist. We have to fight.”

For more on Africa and development: https://apnews.com/hub/africa-pulse

The Associated Press receives financial support for global health and development coverage in Africa from the Gates Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Boys play football as the sun sets in the Mbera Refugee Camp, near Bassikounou, Hodh El Chargui Region, Mauritania, Saturday Nov. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)

Members of the NGO SOS desert plant trees in Mbera Refugee Camp, near Bassikounou, Hodh El Chargui Region, Mauritania, Saturday Nov. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)

Plants flower in the dry desert plains of the Sahel bloom in Mbera Refugee Camp, near Bassikounou, Hodh El Chargui Region, Mauritania, Saturday Nov. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)

Mbera fire brigade members from the NGO SOS desert demonstrate the brushing technique used to extinguish fires in Mbera Refugee Camp, near Bassikounou, Hodh El Chargui Region, Mauritania, Saturday Nov. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)

Mbera fire brigade members from the NGO SOS desert demonstrate the brushing technique used to extinguish fires in Mbera Refugee Camp, near Bassikounou, Hodh El Chargui Region, Mauritania, Saturday Nov. 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Caitlin Kelly)