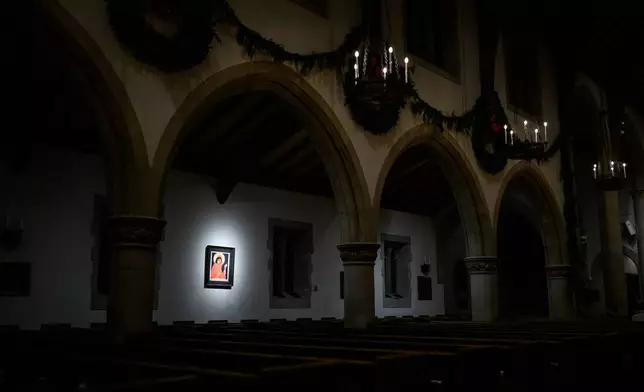

On most Monday nights, the sanctuary of All Saints Episcopal Church — with its vaulted ceilings, stone arches and stained-glass windows — seamlessly transforms into a space of quiet contemplation.

It’s in this Gothic Revival church in Pasadena, California, that Betty Cole, a longtime Zen practitioner and “card-carrying Episcopalian,” leads a weekly interfaith group in seated and walking meditation. The group has evolved into a “quiet fellowship” since she started it in 2001, Cole said.

“It’s mostly people who are really not very inspired by the liturgy, pomp and music of the church, but do enjoy the building, the quiet of the chapel and the sense of encouragement and accountability in that shared quiet,” she said.

Christian, Jewish and other religious congregations across America have in recent years been introducing meditation practices from Eastern religions like Buddhism and Hinduism, or resurfacing ancient contemplative practices in their own religious traditions, now adapted to the needs of a fast-paced, modern world.

While longtime practitioners like Cole say these contemplative practices are inherently spiritual or religious, they recognize that mental health and social benefits are added attributes.

In some deeply religious spaces, meditation has been disparaged as a gateway to the demonic; in some secular circles, it’s debunked as superstition. Skeptics raise concerns over cultural appropriation, particularly in cases where Eastern practices have been marketed as trendy self-improvement.

But nationwide, more people — religious and non-religious — seem to be showing more interest in such practices. Increasingly, houses of worship are encouraging a variety of contemplative practices.

Voices chanting “Om” — a sacred sound in several Eastern religions — blend with sounds of singing bowls, piano and other instruments at meditation held in an Ivy League university chapel. A rabbi leads virtual meditation and breath work while drawing from Jewish scriptures. In the sanctuary of a Unitarian Universalist congregation, a group gathers to study Buddhist dharma and to be enveloped in the meditative practice of a sound bath.

Across centuries, meditation has been common in Buddhism, where the goal is to become enlightened like the Buddha, and Hinduism, in which the ancient spiritual practice of yoga is rooted.

Contemplative and meditative practices in many religions seek to find a direct connection with God. That includes the Desert Fathers and Mothers — early Christian ascetics who followed a form of meditation focused on silence in the Egyptian desert. It also includes Kabbalistic and Hasidic meditation techniques in Jewish tradition, and the whirling dervishes in Sufism, a mystical movement within Islam.

“The next resurgence that we’re seeing now, is people moving all the way out from saying, ‘I’m going to practice a religious tradition’ into ‘I’m willing to do some of the practices that exist within those traditions,’” said Lodro Rinzler, a Buddhist teacher and author of “The Buddha Walks into a Bar.”

For others, Rinzler said, it has helped rekindle a connection to their own religions and their ancient, lesser-known meditative practices.

“Some of the practices that have been spliced out and stand alone are now coming back under the umbrellas,” he said. “People are then being attracted to the traditions from which they’ve always been a part of.”

That’s the case of the Or HaLev — Center for Jewish Spirituality and Meditation. Launched in 2011 by Rabbi James Jacobson-Maisels, it seeks to give people access to a meditation practice rooted in Jewish tradition.

“We’re bringing Hasidic meditations and understandings to a contemporary audience,” said Jacobson-Maisels. “We’re also integrating that with Eastern traditions that have come from the West.”

These meditative practices, he said, are less known, mainly because of the effects of modernity and the Holocaust, which destroyed many communities and teachers who were preserving these traditions.

“As part of Jews’ assimilation to the modern world, many parts of the mystical tradition got rejected or cast aside because they were related to as unacceptable, irrational, not fitting to the modern world,” he said.

“Kabbalah was the most dominant theological paradigm in Judaism. But after modernity, it really was pushed to the side,” he said. “Now it’s experiencing, once again, a resurgence.”

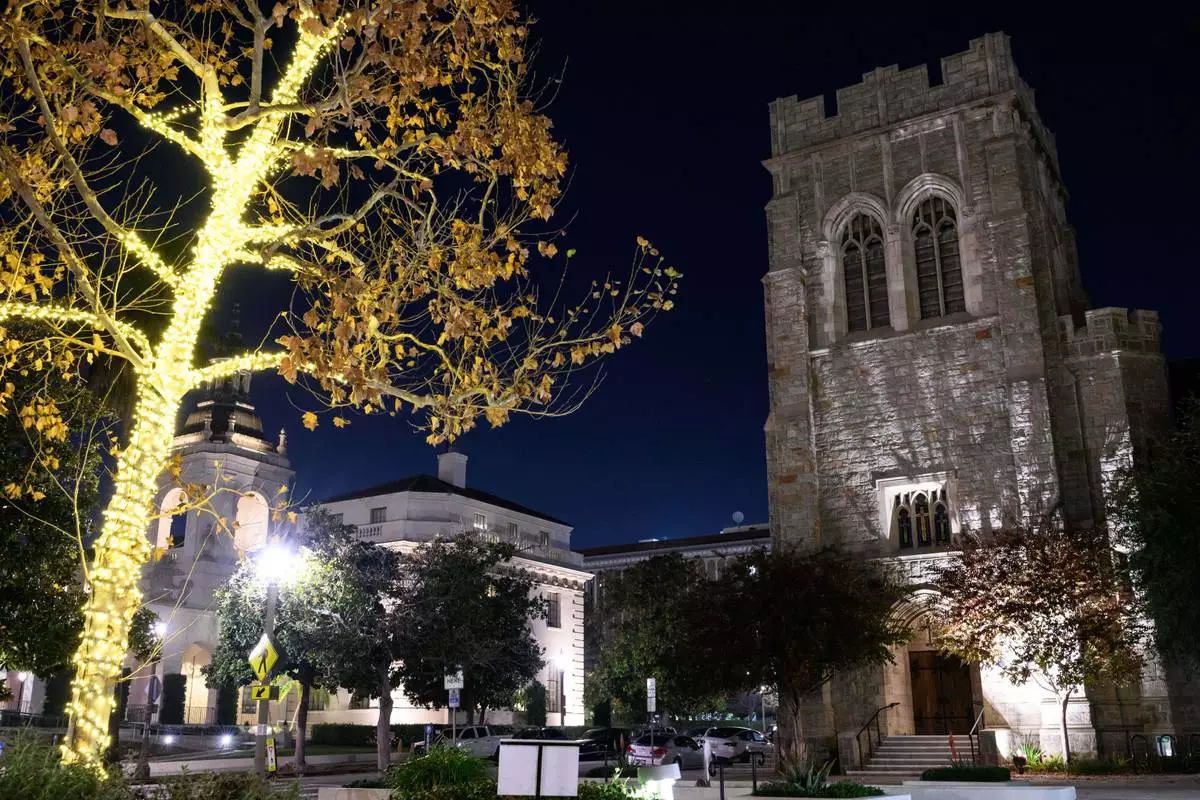

Many have gathered at the Princeton University Chapel to attend meditation events that include chamber music, breathwork and the chanting of mantras.

“The feedback I’ve mostly gotten is that people say, ‘I want to do that again. I don’t know what happened, but I feel like whatever happened, I need more of it,’” said Hope Littwin, a composer who facilitates musical rituals for the meditations.

“People notice the mysterious quality and people feel changed by it,” said Littwin, who is pursuing her PhD in music composition at Princeton.

The university’s Gothic nondenominational chapel hosts concerts, weddings and interfaith services throughout the academic year.

“People from different religions, and even people with no religion at all … connect to meditation because meditation taps us into something universal, something deeper than belief systems or doctrines,” said A.J. Alvarez, a meditation teacher.

Meditation also has become a crucial part of spiritual life at All Souls NYC, a Unitarian Universalist congregation.

When the Rev. Pamela Patton, a Universalist and Buddhist, began the Mindfulness, Meditation, Buddhism program in 2016, she was unsure how it would be received.

In a decade, though, it grew into a community of about 800 members learning from teachers of different Buddhist lineages.

The Universalist religious movement welcomes people with diverse spiritual beliefs. Regarding her program, Patton said, “It’s brought a lot to our community.”

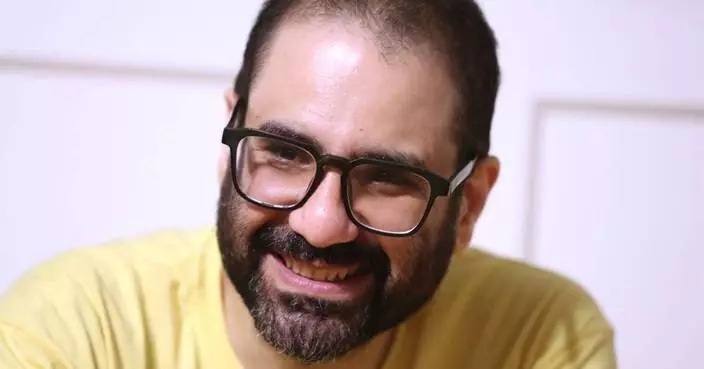

Omid Safi, a professor of religion at Duke University who conducts Sufi meditation tours and retreats, said he sees young Muslims practicing yoga, mindfulness and breath work who are looking to integrate them with their religious identity. That, he said, comes from the recognition that Islam has its own tradition that goes back over 1,000 years developed in conversation with Hindu and Buddhist traditions.

Safi speaks of one fundamental Sufi practice of directing the breath into the subtle centers of perception in the human body called “lataif” — similar to chakras in yoga — but with an important difference.

“In the Sufi model, it's a whirling model that whirls in your inner landscape and enters your heart,” he said. “It’s not about pure transcendence, but balancing earth and heaven.”

Meditation has historically not been done in mosques, but adjacent to them, perhaps with an Islamic teacher leading a session of poetry, music and meditation, Safi said.

In the Sufi tradition, music is “the sound of the movement of the celestial spheres,” he added. “Music is invisible, but you feel it in the heart. Poetry speaks in a symbolic language. The spiritual experiences we have are the same way.”

Susan Stabile, a spiritual director who leads meditation retreats nationwide, said Catholic parishes are seeing a resurgence in contemplative practices, including meditation. Raised Catholic, Stabile became a Buddhist in her 20s and lived as a nun for a few years in Asia. She returned to Catholicism after marrying and having children. Stabile says Buddhism helped her better understand her Christian faith.

“Some in the Catholic tradition are suspicious of some of these contemplative practices such as the centering prayer,” she said, referring to a silent prayer developed in the 1970s by Catholic monastics as a way to deepen a relationship with God.

She said that’s because many Christians are unaware that early Christian hermits developed these practices.

“I didn’t know it was in my own tradition,” she said. “No one had ever told me about it.”

Stabile says she's seeing more people wanting that deeper experience and desiring to learn about mysticism.

“My hope is that more people will allow themselves to be transformed,” she said. “To live more fully in creation and the image and likeness of God.”

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

A painting hangs inside the All Saints Episcopal Church in Pasadena, Calif., on Monday, Dec. 15, 2025. (AP Photo/William Liang)

Participants form a circle to end an interfaith meditation practice at All Saints Episcopal Church in Pasadena, Calif., on Monday, Dec. 15, 2025. (AP Photo/William Liang)

Betty Cole, right, connects with some participants through video call for an interfaith meditation practice at All Saints Episcopal Church in Pasadena, Calif., on Monday, Dec. 15, 2025. (AP Photo/William Liang)

People sit around a table with an orange tapestry gifted by Himalayan refugees, an incense bowl, flowers and a candle during an interfaith meditation practice at All Saints Episcopal Church in Pasadena, Calif., on Monday, Dec. 15, 2025. (AP Photo/William Liang)

The All Saints Episcopal Church in Pasadena, Calif., on Monday, Dec. 15, 2025. (AP Photo/William Liang)

Participants meditate in silence during an interfaith meditation practice at All Saints Episcopal Church in Pasadena, Calif., on Monday, Dec. 15, 2025. (AP Photo/William Liang)

Betty Cole leads an interfaith meditation practice at All Saints Episcopal Church in Pasadena, Calif., on Monday, Dec. 15, 2025. (AP Photo/William Liang)