MIAMI GARDENS, Fla. (AP) — The Miami Dolphins continued an organizational reboot on Thursday, firing coach Mike McDaniel amid an ongoing search for a new general manager.

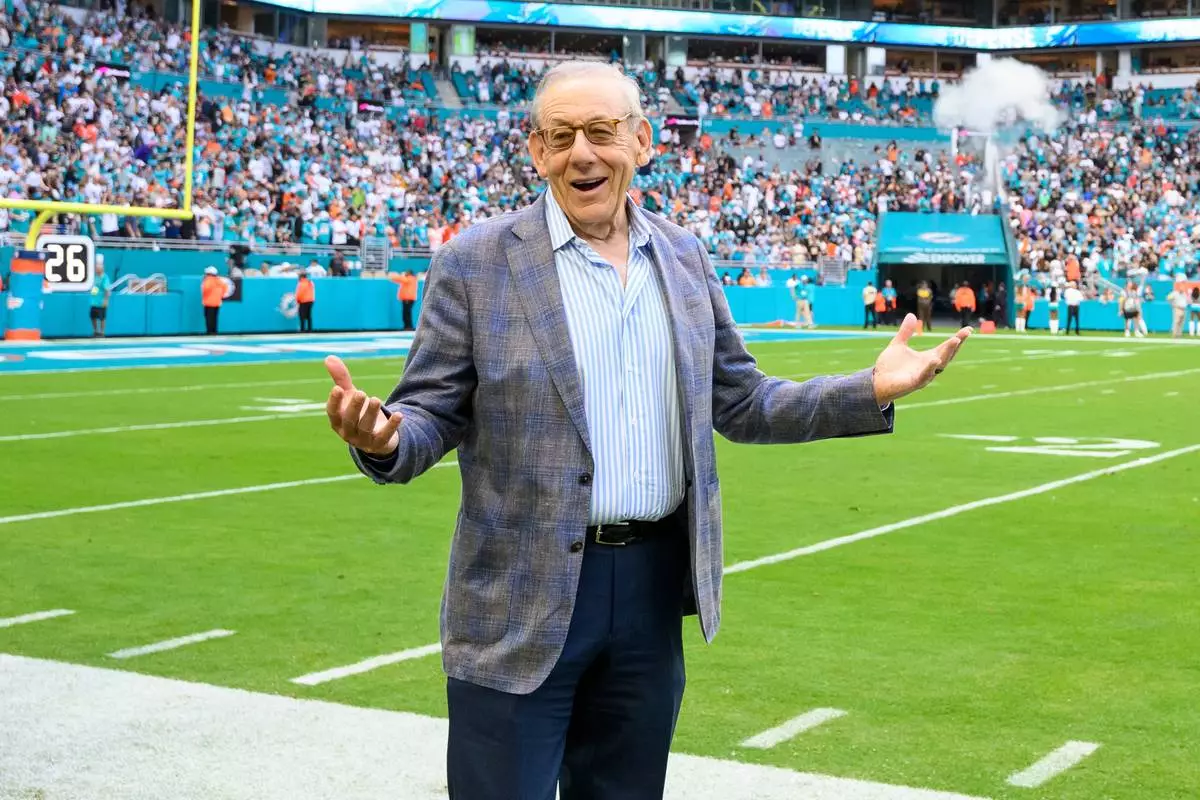

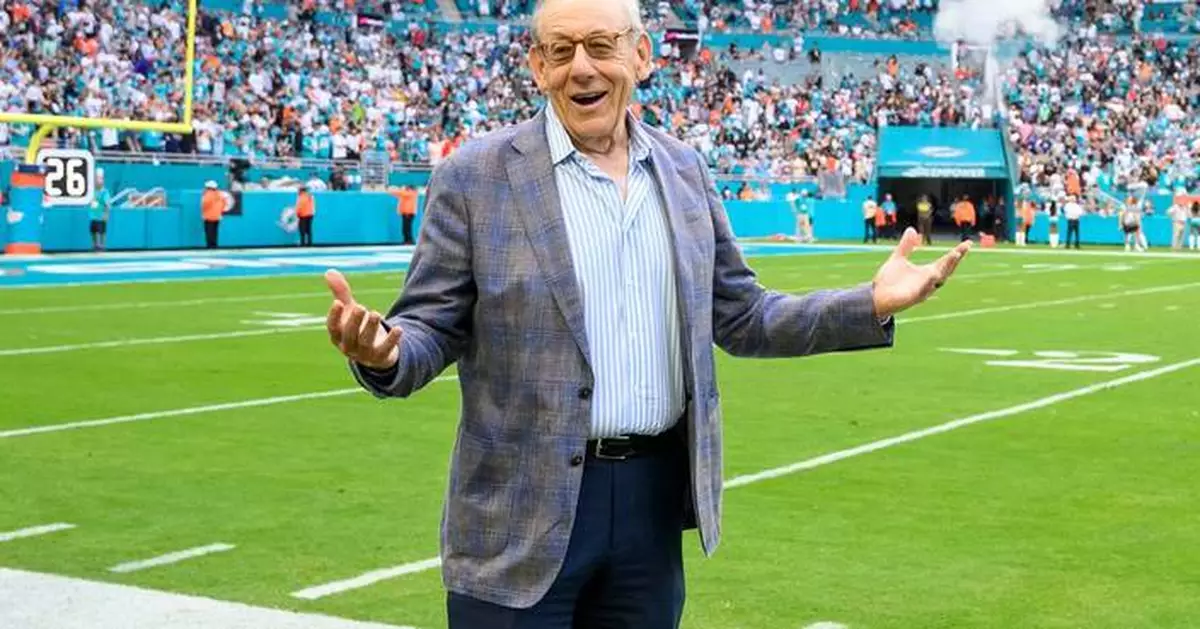

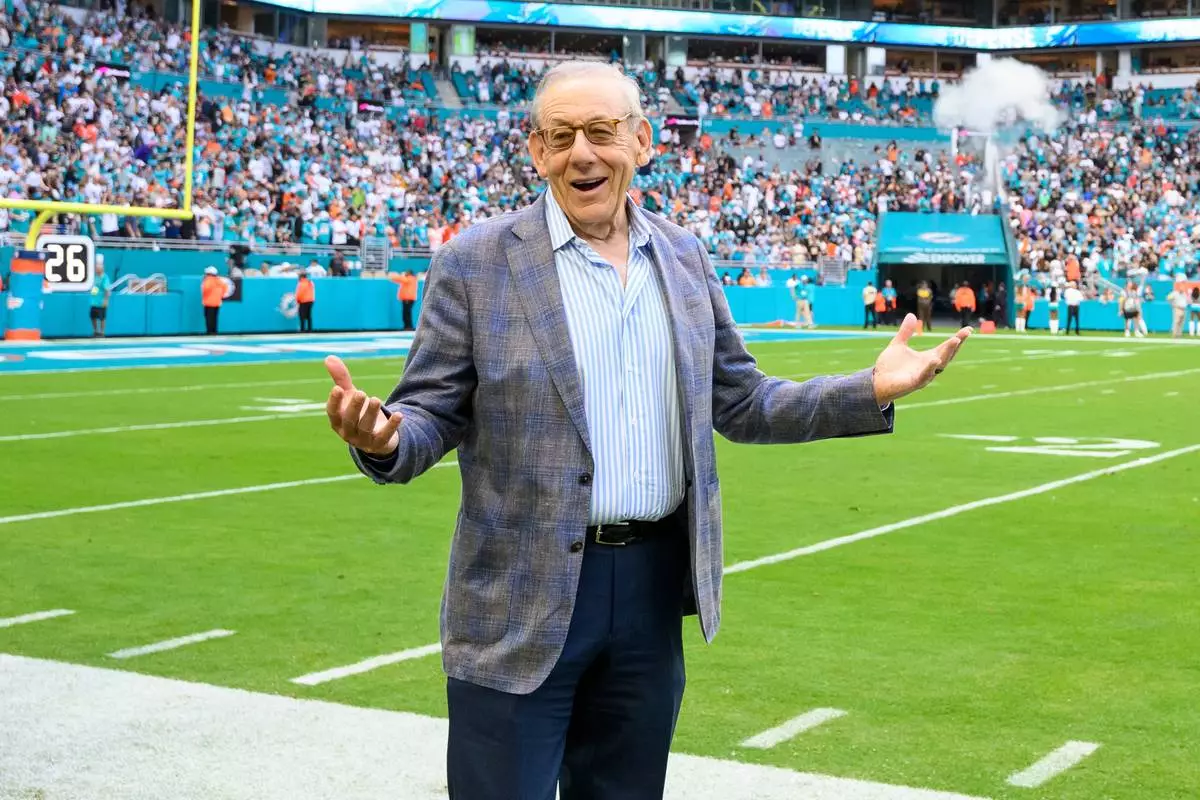

Miami owner Stephen Ross will be looking for his fourth head coach since 2018.

“After careful evaluation and extensive discussions since the season ended, I have made the decision that our organization is in need of comprehensive change,” Ross said in a statement Thursday morning.

There were plenty of indications that a change of some sort would be necessary as Miami's 2025 season unfolded, and Ross parted ways with longtime general manager Chris Grier after a Week 9 loss to the Baltimore Ravens.

Now, following the decision to move on from McDaniel after four seasons, the Dolphins will likely face another full rebuild after gutting their roster in 2019 and stockpiling draft picks.

Miami lost six of its first seven games and finished 7-10, missing the playoffs for a second straight year. Star receiver Tyreek Hill suffered a season-ending knee injury in Week 4, and struggling former first-round pick Tua Tagovailoa was benched by the end of the season.

The Dolphins opened the season with 33-8 drubbing by Daniel Jones and the Colts, a game in which they looked unprepared and did little on either side of the ball. A week later, they were undone by miscues and miscommunication against the Patriots when they had multiple late chances to take the lead.

Many of their other defeats — a 10-point loss to a Bills team McDaniel beat only twice in his tenure, a three-point loss to the Carolina Panthers and a two-point loss to the Los Angeles Chargers — all saw the Dolphins fail to deliver after giving themselves a chance.

One week after squandering a 17-0 lead at Carolina, the Dolphins led Los Angeles by one point with 46 seconds remaining before allowing Justin Herbert to lead his team down the field to set up a game-winning field goal.

Calls for McDaniel’s dismissal were frequent this season. Ahead of Miami's first three home games, fans had crowdsourced a banner that was flown over Hard Rock Stadium calling for his firing.

His players publicly backed him.

“Us as players, we believe in him,” offensive tackle Patrick Paul said during the season. “He believed in me when most didn’t, and he’s a great coach. He’s a players’ coach who believes in his players. He inspires us and speaks confidence into us and makes us go out there with a sense of urgency. ... We love him.”

Ross apparently felt the same way, saying in Thursday's statement that he loves McDaniel.

But with loads of talent to work with during his four years and no playoff wins to show for it, that affection wasn't enough to save McDaniel's job in a results-based league.

Miami joined seven other NFL teams with head coaching vacancies, including Baltimore, which fired longtime coach John Harbaugh on Tuesday.

The Dolphins' immediate concern, though, will be finding a new GM, with Hall of Famer Troy Aikman aiding in that process.

Miami completed an initial phase of interviews with potential candidates earlier this week and was set to hold in-person interviews with four of them.

Among those scheduled for those interviews were Champ Kelly, Miami's interim GM since the midseason firing of Grier; Chargers assistant GM Chad Alexander; Green Bay vice president of player personnel Jon-Eric Sullivan, and San Francisco director of scouting and football operations Josh Williams.

Ross has not hired someone with previous head coaching experience since becoming the Dolphins' majority owner in 2009 — recently gambling on Joe Philbin (2012-2015), Adam Gase (2016-18), Brian Flores (2019-21) and McDaniel (2022-25).

That could change — especially now that a coach with Harbaugh's experience and resume is available.

Many have already linked Harbaugh to Miami, though the coach has reportedly not yet been in talks with the organization.

Following Harbaugh's dismissal by the Ravens on Tuesday, the Dolphins requested an interview with Alexander for their GM opening. Alexander, who joined the Chargers' front office ahead of the 2024 season, has a long history with Harbaugh, having worked in various roles for the Ravens over 20 seasons.

Ross, a Michigan graduate, also a has ties to the Harbaugh family. He has poured in millions of dollars to the university as a donor and has previously pursued Jim Harbaugh to coach the Dolphins.

If Ross decides to take a chance on another inexperienced coach, he may consider Anthony Weaver, Miami's defensive coordinator who has interviewed for head coaching jobs the past few years and is already well-regarded by Dolphins players.

Other experienced targets could include former Cowboys and Packers coach Mike McCarthy; Vance Joseph, the Denver Broncos defensive coordinator who had the same role with the Dolphins in 2016; or Kevin Stefanski, who was recently fired by Cleveland.

AP NFL: https://apnews.com/hub/nfl

Miami Dolphins head coach Mike McDaniel walks away after an end-of-season NFL football news conference, Monday, Jan. 5, 2026, in Miami Gardens, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

Baltimore Ravens head coach John Harbaugh watches during the first half of an NFL football game against the Green Bay Packers, Saturday, Dec. 27, 2025, in Green Bay, Wis. (AP Photo/Matt Ludtke)

FILE - Miami Dolphins owner Stephen Ross gestures and smiles as he celebrates the Dolphins defeating the New Orleans Saints during an NFL football game, Nov. 30, 2025, in Miami Gardens, Fla. (AP Photo/Doug Murray, File)

CARACAS, Venezuela (AP) — At the White House, President Donald Trump vows American intervention in Venezuela will pour billions of dollars into the country’s infrastructure, revive its once-thriving oil industry and eventually deliver a new age of prosperity to the Latin American nation.

Here at a sprawling street market in the capital, though, utility worker Ana Calderón simply wishes she could afford the ingredients to make a pot of soup.

“Food is incredibly expensive,” says Calderón, noting rapidly rising prices that have celery selling for twice as much as just a few weeks ago and a kilogram (2 pounds) of meat going for more than $10, or 25 times the country’s monthly minimum wage. “Everything is so expensive.”

Venezuelans digesting news of the United States’ brazen capture of former President Nicolás Maduro are hearing grandiose promises of future economic prowess even as they live through the crippling economic realities of today.

“They know that the outlook has significantly changed but they don’t see it yet on the ground. What they’re seeing is repression. They’re seeing a lot of confusion,” says Luisa Palacios, a Venezuelan-born economist and former oil executive who is a research scholar at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University. “People are hopeful and expecting that things are going to change but that doesn’t mean that things are going to change right now.”

Whatever hope exists over the possibility of U.S. involvement improving Venezuela’s economy is paired with the crushing daily truths most here live. People typically work two, three or more jobs just to survive, and still cupboards and refrigerators are nearly bare. Children go to bed early to avoid the pang of hunger; parents choose between filling a prescription and buying groceries. An estimated eight in 10 people live in poverty.

It has led millions to flee the country for elsewhere.

Those who remain are concentrated in Venezuela’s cities, including its capital, Caracas, where the street market in the Catia neighborhood once was so busy that shoppers bumped into one another and dodged oncoming traffic. But as prices have climbed in recent days, locals have increasingly stayed away from the market stalls, reducing the chaos to a relative hush.

Neila Roa, carrying her 5-month-old baby, sells packs of cigarettes to passersby, having to monitor daily fluctuations in currency to adjust the price.

“Inflation and more inflation and devaluation,” Roa says. “It’s out of control.”

Roa could not believe the news of Maduro’s capture. Now, she wonders what will come of it. She thinks it would take “a miracle” to fix Venezuela’s economy.

“What we don’t know is whether the change is for better or for worse,” she says. “We’re in a state of uncertainty. We have to see how good it can be, and how much it can contribute to our lives.”

Trump has said the U.S. will distribute some of the proceeds from the sale of Venezuelan oil back to its population. But that commitment so far largely appears to be focused on America’s interests in extracting more oil from Venezuela, selling more U.S.-made goods to the country and repairing the electricity grid.

The White House is hosting a meeting Friday with U.S. oil company executives to discuss Venezuela, which the Trump administration has been pressuring to open its vast-but-struggling oil industry more widely to American investment and know-how. In an interview with The New York Times, Trump acknowledged that reviving the country’s oil industry would take years.

“The oil will take a while,” he said.

Venezuela has the world's largest proven oil reserves. The country's economy depends on them.

Maduro's predecessor, the fiery Hugo Chávez, elected in 1998, expanded social services, including housing and education, thanks to the country’s oil bonanza, which generated revenues estimated at some $981 billion between 1999 and 2011 as crude prices soared. But corruption, a decline in oil production and economic policies led to a crisis that became evident in 2012.

Chávez appointed Maduro as his successor before dying of cancer in 2013. The country’s political, social and economic crisis, entangled with plummeting oil production and prices, marked the entirety of Maduro's presidency. Millions were pushed into poverty. The middle class virtually disappeared. And more than 7.7 million people left their homeland.

Albert Williams, an economist at Nova Southeastern University, says returning the energy sector to its heyday would have a dramatic spillover effect in a country in which oil is the dominant industry, sparking the opening of restaurants, stores and other businesses. What's unknown, he says, is whether such a revitalization happens, how long it would take and how a government built by Maduro will adjust to the change in power.

“That’s the billion-dollar question,” Williams says. “But if you improve the oil industry, you improve the country.”

The International Monetary Fund estimates Venezuela’s inflation rate is a staggering 682%, the highest of any country for which it has data. That has sent the cost of food beyond what many can afford. Venezuela’s monthly minimum wage of 130 bolivars, or $0.40, has not increased since 2022, putting it well below the United Nations’ measure of extreme poverty of $2.15 a day.

The currency crisis led Maduro to declare an “economic emergency” in April.

Usha Haley, a Wichita State University economist who studies emerging markets, says for those hurting the most, there is no immediate sign of change.

“Short-term, most Venezuelans will probably not feel any economic relief,” she says. “A single oil sale will not fix the country’s rampant inflation and currency collapse. Jobs, prices, and exchange rates will probably not shift quickly.”

In a country that has seen as much strife as Venezuela has in recent years, locals are accustomed to doing what they have to in order to get through the day, so much so that many utter the same expression

“Resolver,” they say in Spanish, or “figure it out," shorthand for the jury-rigged nature of life here, in which every transaction, from boarding a bus to buying a child's medicine, involves a delicate calculation.

Here at the market, the smell of fish, fresh onions and car exhaust combine. Calderon, making her way through, faces freshly skyrocketing prices, saying “the difference is huge,” as the country’s official currency has rapidly declined against its unofficial one, the U.S. dollar.

Unable to afford all the ingredients for her soup, she left with a bunch of celery but no meat.

Sedensky reported from New York. Associated Press writer Josh Boak in Washington contributed to this report.

A barber cuts hair at a barbershop in Caracas, Venezuela, Tuesday, Jan. 6, 2026. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A kite flies over the Petare neighborhood of Caracas, Venezuela, Wednesday, Jan. 7, 2026. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Vendors display vegetables at a street market in Caracas, Venezuela, Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

People exchange U.S. dollars for Venezuelan bolivars at a street market in Caracas, Venezuela, Thursday, Jan. 8, 2026. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A woman sits in front of a store in the Petare neighborhood of Caracas, Venezuela, Wednesday, Jan. 7, 2026. (AP Photo/Cristian Hernandez)