PARIS (AP) — Valentino Garavani’s death cast a long shadow over the opening day of Paris Fashion Week menswear Tuesday, with front-row guests and industry figures mourning the passing of one of the last towering names of 20th-century couture — an Italian designer whose working life was closely entwined with the Paris runways.

Valentino, 93, died at his Rome residence, the Valentino Garavani and Giancarlo Giammetti Foundation said in a statement announcing his death. While he built his house in Rome, he spent decades presenting collections in France.

He “was one of the last big couturiers who really embodied what was fashion in the 20th century,” said Pierre Groppo, fashion editor-in-chief at Vanity Fair France.

On a day meant to sell the future, many guests said they were thinking about what fashion has lost: the couturier as a living institution.

Groppo pointed to the codes that made Valentino instantly legible — “the dots, the ruffles, the knots” — and to a generation of designers who, he said, “in a way, invented what is celebrity culture.”

Valentino’s vision was built on a simple idea: make women look luminous, then make the moment unforgettable.

He dressed Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Elizabeth Taylor, among others, fixed his signature “Valentino red” in the public imagination, and — through his decades-long partnership with Giancarlo Giammetti — helped turn the designer himself into part of the spectacle, as recognizable as the clients in his front row.

Prominent fashion writer Luke Leitch framed the loss in similarly outsized terms, calling Valentino “the last of the fashion ‘leviathans of that generation’,” and saying it was “absolutely” the end of a certain class of designer: figures whose names could carry a global house, and whose authority came not from viral speed but from permanence.

Trained in Paris before founding his maison in Rome, Valentino became a rare bridge figure: Italian by origin, but fluent in the rituals that made Paris couture an institution. His career moved between those two capitals of elegance, bringing Roman grandeur into a system that still treats fashion not only as commerce, but as ceremony.

Even as he aged, the house’s founder kept turning up at its couture and ready-to-wear shows, as observed by one Associated Press journalist — until he eventually retreated from public life, all the while radiating quiet grandeur from his front-row seat.

For some in Paris on Tuesday, the loss felt personal precisely because Valentino’s world was never only Italian.

Groppo recalled the designer as “very much more than a fashion brand,” adding: “It was a lifestyle.”

That lifestyle — couture polish, social glamour, and the conviction that elegance could be a form of power — remains a reference point even as fashion accelerates toward louder branding and faster cycles.

“It’s quite sad as he’s so important to the fashion industry, and he contributed a lot and I cannot forget the stunning red he created,” said Lolo Zhang, a Chinese fashion influencer attending Louis Vuitton ’s show in Paris.

“He always celebrated pure beauty, and architecture for the silhouette, and how he used color. The old era just passed by.”

Other guests described a delayed realization — the kind that arrives only when a figure who seemed permanent is suddenly gone.

“There are some people who want to be Yves Saint Laurent, Chanel. ... There are also people who are spontaneously Valentino,” said Guy-Claude Agboton, deputy editor of Ideat magazine. “It’s a question of identity.”

For Paris fashion observer Benedict Epinay, the grief was bound up with memory. And with the emotional charge of Valentino’s final bow.

“It was such a great moment. I was lucky enough to attend the last show he gave,” Epinay said. “It was so moving because we knew at that time it was the last show.”

Fashion observer Arfan Ghani pointed to what Valentino represented to younger designers: a “classy” standard of restraint in an era that often rewards noise.

“Because it was very classical materials," Ghani said. "It wasn’t as loud as a lot of other of these brands are with branding.”

Paris-based sculptor Ranti Bam described Valentino in the language of form: less trend than structure, less look than line.

“As a sculptor I saw Valentino as an artist,” Bam said. “He transcended fashion into sculpture.”

“He didn’t follow trends, he pursued form,” she added. “That’s why his work doesn’t date, it endures.”

The fashion house Valentino has for years continued under a new generation of leadership and design — still showcased in Paris.

Corrects previous misspellings of Paris fashion observer Benedict Epinay and Guy-Claude Agboton, deputy editor of Ideat magazine.

Associated Press writer Amy Seraphin in Paris contributed to this report.

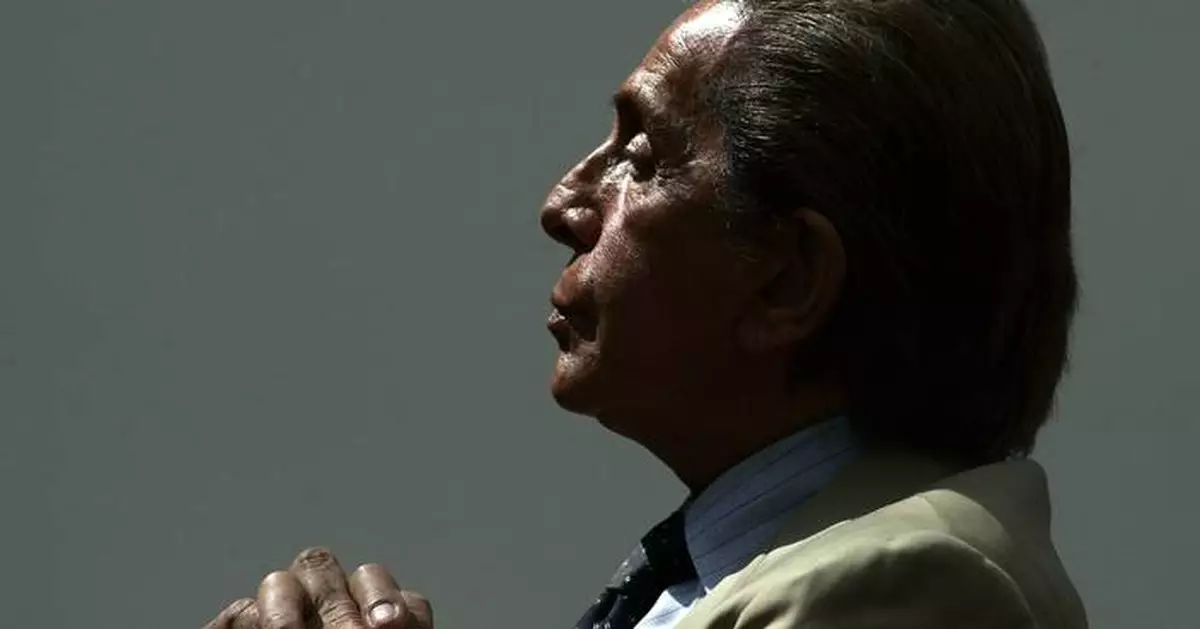

FILE - Italian fashion designer Valentino Garavani looks on during a press conference at Rome's Capitoline museums, Wednesday, June 13, 2007, on the occasion of the 45th anniversary of Valentino Maison foundation. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia, File)

BUFFALO, N.Y. (AP) — In two decades of kicking in doors for the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, Joseph Bongiovanni often took on the risks of being the “lead breacher," meaning he was the first person into the room.

On Wednesday, he felt a familiar uncertainty awaiting sentencing for using his DEA badge to protect childhood friends who became prolific drug traffickers in Buffalo, New York.

“I never knew what was on the other side of that door — that fear is what I feel today,” Bongiovanni, 61, told a federal judge, pounding the defense table as his face reddened with emotion. “I've always been innocent. I loved that job.”

U.S. District Court Judge Lawrence J. Vilardo sentenced the disgraced lawman to five years in federal prison on a string of corruption counts. The punishment was significantly less than the 15 years prosecutors sought even after a jury acquitted Bongiovanni of the most serious charges he faced, including an allegation he pocketed $250,000 in bribes from the Mafia.

The judge said the sentence reflected the complexity of the mixed verdicts following two lengthy trials and the almost Jekyll-and-Hyde nature of Bongiovanni's career, in which the lawman racked up enough front-page accolades to fill a trophy case.

Bongiovanni once hurtled into a burning apartment building to evacuate residents through billowing smoke. He locked up drug dealers, including the first ever prosecuted in the region for causing a fatal overdose.

“There are two completely polar opposite versions of the facts and polar opposite versions of the defendant,” Vilardo said, assuring prosecutors five years behind bars would pose a considerable hardship to someone who has never been to prison.

Defense attorney Parker MacKay noted the judge had acknowledged Bongiovanni as a “beacon” of the Buffalo community. The government's request for a 15-year sentence, he added, was “completely unmoored to the nature of the convictions.”

“As Mr. Bongiovanni told the judge at sentencing, he is innocent, and we look forward to continuing to work with him to prove that,” MacKay told The Associated Press.

A jury in 2024 convicted Bongiovanni of four counts of obstruction of justice, counts of conspiracy to defraud the United States, conspiracy to distribute controlled substances and making false statements to law enforcement.

Prosecutors said Bongiovanni's “little dark secret” caused immeasurable damage over 11 years. They likened him to Jose Irizarry, a disgraced former DEA agent serving a 12-year federal sentence after confessing to laundering money for Colombian drug cartels.

Bongiovanni upheld an oath not to the DEA, they argued, but to organized crime figures in the tight-knit Italian American community of his North Buffalo upbringing. During sentencing, Bongiovanni’s family dissolved into tears on the front row of the packed courtroom in downtown Buffalo.

Prosecutors said Bongiovanni's corruption involved as much inaction as calculated coverup. They pointed to a turning point in 2008 when Bongiovanni could have acted on intelligence about traffickers he knew whose operation would evolve into a large-scale organization with links to California, Vancouver, and New York City.

He also was accused of authoring bogus DEA reports, stealing sensitive files, throwing off colleagues, outing confidential informants, covering for a sex-trafficking strip club and helping a high school English teacher keep his marijuana-growing side hustle. Prosecutors said he brazenly urged colleagues to spend less time investigating Italians and focus instead on Black and Hispanic people.

“His conduct shook the foundation of law enforcement — and this community — to its core,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Joseph Tripi told the judge. “That's what a betrayal is.”

The ex-agent's downfall came amid a sex-trafficking prosecution that took sensational turns, including an implicated judge who killed himself after the FBI raided his home, law enforcement dragging a pond in search of an overdose victim and dead rats planted outside the home of a government witness who prosecutors allege was later killed by a fatal dose of fentanyl.

It also involved the Pharoah’s Gentlemen’s Club outside Buffalo. Bongiovanni was childhood friends with the strip club’s owner, Peter Gerace Jr., who authorities say has close ties to both the Buffalo Mafia and the violent Outlaws Motorcycle Club. A separate jury convicted Gerace of a sex trafficking conspiracy and of paying bribes to Bongiovanni.

The prosecution also cast a harsh light on the DEA after a string of corruption scandals prompted at least 17 agents brought up on federal charges over the past decade. Last month, prosecutors charged another former agent with conspiring to launder millions of dollars and obtain military-grade firearms and explosives for a Mexican drug cartel.

Frank Tarentino, the DEA’s northeast associate chief of operations, said Bongiovanni’s sentence “sends a powerful message that those who betray their badge will be held accountable to the fullest extent of the law.”

Joseph Bongiovanni, center, leaves federal court with his wife, Lindsay Bongiovanni, right, after being sentenced to 5 years in prison on corruption charges, Wednesday, Jan. 21, 2026, in Buffalo, N.Y. (AP Photo/Jim Mustian)

Joseph Bongiovanni, left, leaves federal court with his wife, Lindsay Bongiovanni, after being sentenced to 5 years in prison on corruption charges, Wednesday, Jan. 21, 2026, in Buffalo, N.Y. (AP Photo/Jim Mustian)