BUDAPEST, Hungary (AP) — Hungary's pro-Russian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán accused Ukraine on Monday of seeking to meddle in his country's upcoming elections and ordered Kyiv's ambassador to be summoned to the foreign ministry.

The step was the latest in Orbán's long-running anti-Ukraine campaign as he seeks to convince voters that the neighboring country, embroiled in a war with Russia since the full-scale invasion began in February 2022, poses an existential threat to Hungary's security and sovereignty.

Orbán, who has maintained close ties with Russia, faces what is expected to be the biggest challenge of his 16 years in power during elections scheduled for April 12.

With his right-wing nationalist Fidesz party trailing by double digits in most polls, Orbán has campaigned on the unsubstantiated premise that Hungarians would be forcibly conscripted to fight and die on the front lines in Ukraine if his party loses the election.

In a video posted to social media on Monday, Orbán said Ukraine's political leaders, and “even the president himself, made grossly offensive and threatening statements against Hungary and the Hungarian government.”

Orbán did not specify which statements he was referring to.

“Our national security services have evaluated this latest Ukrainian attack and determined that what happened is part of a coordinated series of Ukrainian measures to interfere in the Hungarian elections,” Orbán said, adding he'd instructed the foreign minister to summon Ukraine's ambassador.

As Hungary's elections approach, Orbán in the last year has escalated a sweeping anti-Ukraine campaign and, without providing evidence, accused his leading rival, opposition leader Péter Magyar, of entering into a pact with Kyiv to overthrow his government and install a pro-Western, pro-Ukraine administration.

Hungary's government has strongly opposed European Union financial and military aid for Ukraine, and vowed that it would veto any EU steps toward its accession into the bloc. This month, Orbán's government launched what it calls a “national petition” which it has urged voters to sign in opposition to continued EU financial support for Kyiv.

Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland last week, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy criticized Orbán, saying he “lives off European money while trying to sell out European interests.”

“If he feels comfortable in Moscow, it doesn't mean we should let European capitals become little Moscows,” Zelenskyy said of Orbán.

Prime Minister of Hungary Viktor Orban arrives during the Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Thursday, Jan. 22, 2026. (AP Photo/Markus Schreiber)

TEL AVIV, Israel (AP) — In the last months of World War II, Lola Kantorowicz tried her best to hide her pregnancy. She succeeded because most of the prisoners at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp had bellies that were distended and bloated from extended starvation.

As she went into labor in March 1945, the Russians were advancing through Germany, and Bergen-Belsen was in chaos. Her daughter, Ilana, was born on March 19, 30 days before the camp was liberated by the British.

Now 81, Ilana Kantorowicz Shalem is among the youngest Holocaust survivors. She survived only because she was born when the Nazi leadership was in disarray as the war was ending. Otherwise, she most certainly would have been killed.

More than eight decades after the end of the Holocaust, Shalem is sharing her story — and her mother’s story — for the first time, realizing how few Holocaust survivors are left.

International Holocaust Remembrance Day is observed across the world on Jan. 27, the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, the most notorious of the death camps where some 1.1 million people, most of them Jews, were killed. The U.N. General Assembly adopted a resolution in 2005 establishing the day as an annual commemoration.

About 6 million European Jews and millions of other people, including Poles, Roma, people with disabilities and LGBTQ+ people, were killed by the Nazis and their collaborators. Some 1.5 million were children.

Commemorations this year are taking place amid a rise of antisemitism that gained traction during the two-year-long war between Israel and Hamas in Gaza.

Shalem’s mother and father met as teenagers in the Tomaszow Ghetto in Poland. Lola Rosenblum was from the town, while Hersz (Zvi) Abraham Kantorowicz was moved to the ghetto from Lodz, Poland.

After spending several years in the ghetto under hard labor conditions, including losing family members, they were shuffled through several labor camps, where they were able to continue meeting clandestinely for several months.

“My mother said there was actually a lot of love in those places,” Shalem recalled of the labor camps. “They used to walk along the river. There was romance.”

Her mother’s friends used to help set up secret meetings between the two, who had married in an informal ceremony back in the ghetto.

In 1944, the couple was separated. Hersz Kantorowicz would eventually perish in a death march just days before the war ended. Lola spent time in Auschwitz and the Hindenburg labor camp. She completed a death march to Bergen-Belsen in Germany while pregnant.

“If they discovered she was pregnant, they would have killed her,” Shalem said. “She hid her pregnancy from everyone, including her friends, because she didn’t want the extra attention or anyone to give her their food."

Yad Vashem archivist Sima Velkovich, who has researched Shalem’s story, called it “unimaginable” that a baby was born in such conditions.

“In March, the conditions were really awful, there were mountains of corpses,” Velkovich said. “There were thousands, dozens of thousands of people who were ill, almost without food at that time.”

To this day, Shalem doesn’t have an explanation for how her mother not only survived the conditions of the camp but gave birth to a healthy baby. Mother and daughter spent a month in the Bergen-Belsen camp before it was liberated by the British, and then two years in a nearby camp for displaced persons.

They then moved to Israel, where her father’s parents had moved before the war. Shalem's mother held out hope for years that her father had survived. She never married again, nor had additional children.

In the immediate months after the war, baby Ilana was constantly fussed over, one of the only children in the refugee camp.

“Actually, I was everyone’s child, because for them, it was some kind of sign of life,” Shalem said. “Many, many women took care of me there, because they were very excited to be with a little baby.”

Photos from that time show a beaming baby Ilana surrounded by a cadre of adults. Her mother’s friends spoke of her as “a new seed,” and a ray of hope during a dark time, Shalem said.

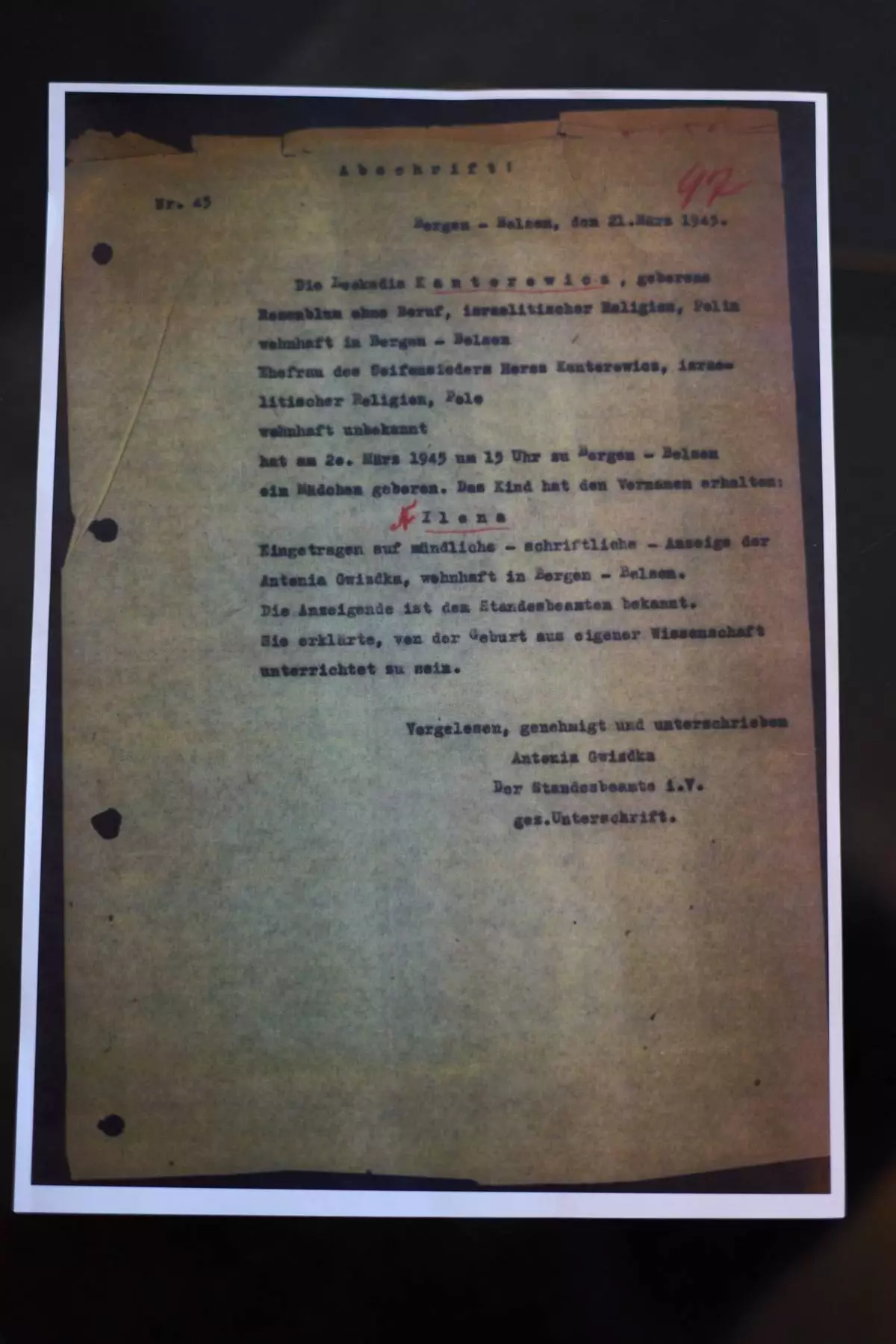

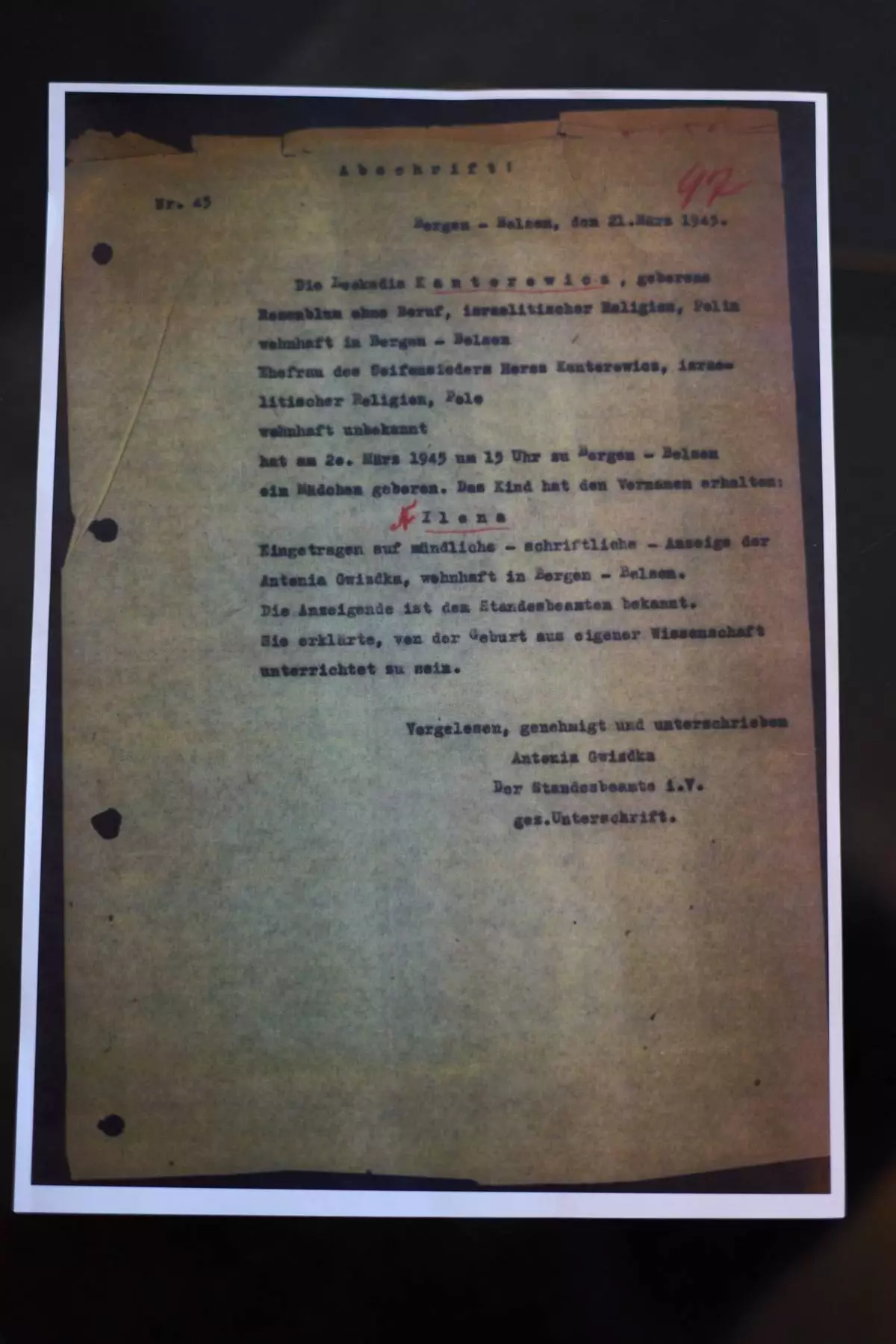

She’s not aware of any other children born in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp who survived. Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust museum and research center, has documented over 2,000 babies born at the Bergen-Belsen refugee camp after its liberation, between 1945 and 1950. The museum at Bergen-Belsen was able to locate documentation of Ilana’s birth, including the hour she was born, which is now kept at Yad Vashem.

Shalem, who studied social work, started asking her mother questions while she was in university in the 1960s, when it was still taboo in Israeli society to dig into the experiences of survivors.

“Now we know, in order to absorb trauma, we need to talk about it,” Shalem said. “These people didn’t want to talk about it.”

She noted how, in the wake of the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas-led attack on southern Israel, many survivors of that attack immediately began to speak about what happened to them.

But the aftermath of the Holocaust, especially in Israel, was different. Many survivors were trying to forget what had happened. Ilana’s mother often faced disbelief when she shared her story of giving birth in a concentration camp, so she mostly stopped telling it. Sometimes her mother would talk about what she endured with other survivor friends, but rarely with strangers, Shalem said.

Shalem has never publicly shared the story of her mother, who died in 1991 at the age of 71. Last year, she completed a genealogy course at Yad Vashem and began to understand how few Holocaust survivors are left to share their stories.

According to the New York-based Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, also referred to as the Claims Conference, there are approximately 196,600 living Holocaust survivors, half of whom live in Israel. Nearly 25,000 Holocaust survivors died last year. The median age of Holocaust survivors is 87, meaning most were very young children during the Holocaust. Shalem is among the youngest.

Shalem, who has two daughters, remembers sharing her own pregnancies with her mother, and marveling at what she had endured.

“It’s a situation that was very unusual, it probably required special strength to be able to believe,” Shalem said.

“She said that one of the things was that if she had known my father was killed, she wouldn’t have tried so hard. She wanted him to know me.”

A Photo of the birth certificate of Holocaust survivor Ilana Shalem-Kantorowics, born in the Nazi Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in 1946 , is on display in Tel Aviv, Israel, Jan. 26, 2026. (AP Photo/Ariel Schalit)

Photos of Holocaust survivor Ilana Shalem-Kantorowics born in the Nazi Bergen-Belsen concentration camp with her with mother Lola in the camp in 1946, in Tel Aviv, Israel, Jan. 26, 2026. (AP Photo/Ariel Schalit)

Holocaust survivor Ilana Shalem-Kantorowics, born in the Nazi Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, holds a photo of her with her mother Lola taken in the camp in 1946, in Tel Aviv, Israel, Jan. 26, 2026. (AP Photo/Ariel Schalit)

Holocaust survivor Ilana Shalem-Kantorowics born in the Nazi Bergen-Belsen concentration camp holds a photo of her with her mother Lola in the camp in 1946, in Tel Aviv, Israel, Jan. 26, 2026. (AP Photo/Ariel Schalit)