JIKANDOR, Liberia (AP) — The announcement posted in the village has a cheerful tone: “BMMC is pleased to inform you that there will be a blast” at a mining pit nearby.

Residents told visiting journalists with The Associated Press and The Gecko Project that such explosions have cracked or crumbled homes during the operations of Liberia’s largest gold miner, the Bea Mountain Mining Corporation.

Click to Gallery

An aerial view shows a forest where Bea Mountain Mining Corporation is conducting exploration near Gbargbo Village, Liberia, July 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Boima G. Kamara, who has lived his entire life in Jikando, is preparing to relocate because mining pollution has poisoned the river his village depends on, July 8, 2025, in Jikando, Liberia. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Residents express their disappointment with the failure of Bea Mountain Mining Corporation to deliver promises such as schools, hospitals and employment, July 11, 2025, in Gbargbo, Liberia. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Flomo Zaza, whose farm was invaded by displaced elephants due to deforestation, stands in his backyard garden, which he relies on to feed his family in Zaza village, Liberia, July 8, 2025. "They ate everything," Zaza said. "We don't have any place to go. We are going to die if it continues." (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Children play in the village of Jikando, Liberia, July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Residents are preparing to relocate from their village after the river they depend on was poisoned by mining waste in Jikando, Liberia, July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Hawa Manubah, a mother of 13, leaves the ruins of her former home, which she says was damaged by concussions from mining explosives, in Gold Camp, Liberia. "We were in the house when we heard the blasting sound-boom, and everyone ran away," she said on July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

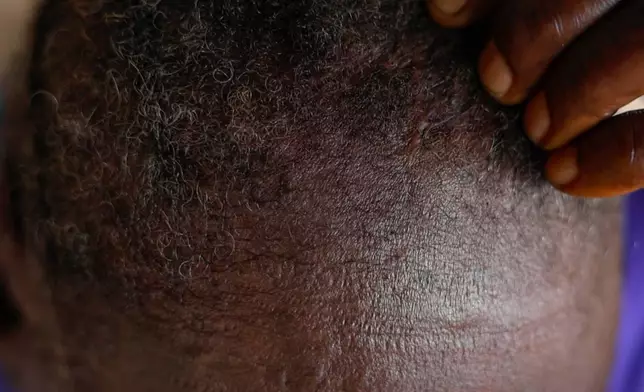

Satta Surtual shows a scar from an injury sustained during a protest in Gogioma, Liberia, July 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

People walk on through Kinjor, Liberia, on July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Marie Pearl stands by her house, which has developed cracks that she blames on blasting at a nearby mine site in Gold Camp, Liberia, July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

A sign gives directions to the New Liberty Gold Mine, operated by Bea Mountain Mining Corporation, in Grand Cape Mount County, Liberia, July 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

An aerial view shows Bea Mountain's N'dablama mine site and Gold Camp Community, Liberia, July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Mustapha Pabai, the town chief, walks beside a polluted river, in Jikando, Liberia, July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

An aerial view shows mining waste flowing into a large pond at an inland location east of Grand Cape Mount, not far from the Mano River in Liberia, July 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

The journalists’ investigation into the company found multiple spills of cyanide and other toxic chemicals by its largest mine into waterways, incidents documented by Liberia’s environmental regulators in reports that were removed from public view.

But concerns go beyond the spills. The mining operation also has cleared 2,200 hectares (5,436 acres) of rain forest, an area six times the size of New York’s Central Park. Such forests are home to endangered species, including pygmy hippos and Western chimpanzees.

Half of Liberia’s forested area is covered by proposed or active mining licenses for Bea Mountain or other firms, according to a report last year by the nonprofit Forest Trends.

In villages near the largest Bea Mountain mine, other grievances emerged. Some residents asserted that the mining company had failed to deliver on promised training to help villagers obtain senior management positions in its operations.

Residents recalled the anger that spilled over in 2024 in protests against the mining operations that they said police ended with tear gas and deadly force. One woman showed what she said was a scar on her scalp from a tear gas canister.

“The blood was coming down and I fell unconscious,” Satta Surtual said. Police denied using excessive force.

These are the tensions that often underlay mining operations across the African continent, where experts say regulation and oversight can be weak.

This is a documentary photo story curated by AP photo editors.

An aerial view shows a forest where Bea Mountain Mining Corporation is conducting exploration near Gbargbo Village, Liberia, July 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Boima G. Kamara, who has lived his entire life in Jikando, is preparing to relocate because mining pollution has poisoned the river his village depends on, July 8, 2025, in Jikando, Liberia. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Residents express their disappointment with the failure of Bea Mountain Mining Corporation to deliver promises such as schools, hospitals and employment, July 11, 2025, in Gbargbo, Liberia. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Flomo Zaza, whose farm was invaded by displaced elephants due to deforestation, stands in his backyard garden, which he relies on to feed his family in Zaza village, Liberia, July 8, 2025. "They ate everything," Zaza said. "We don't have any place to go. We are going to die if it continues." (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Children play in the village of Jikando, Liberia, July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Residents are preparing to relocate from their village after the river they depend on was poisoned by mining waste in Jikando, Liberia, July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Hawa Manubah, a mother of 13, leaves the ruins of her former home, which she says was damaged by concussions from mining explosives, in Gold Camp, Liberia. "We were in the house when we heard the blasting sound-boom, and everyone ran away," she said on July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Satta Surtual shows a scar from an injury sustained during a protest in Gogioma, Liberia, July 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

People walk on through Kinjor, Liberia, on July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Marie Pearl stands by her house, which has developed cracks that she blames on blasting at a nearby mine site in Gold Camp, Liberia, July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

A sign gives directions to the New Liberty Gold Mine, operated by Bea Mountain Mining Corporation, in Grand Cape Mount County, Liberia, July 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

An aerial view shows Bea Mountain's N'dablama mine site and Gold Camp Community, Liberia, July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Mustapha Pabai, the town chief, walks beside a polluted river, in Jikando, Liberia, July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

An aerial view shows mining waste flowing into a large pond at an inland location east of Grand Cape Mount, not far from the Mano River in Liberia, July 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

JIKANDOR, Liberia (AP) — An investigation by The Associated Press and The Gecko Project has found that the largest gold mining company in Liberia repeatedly spilled toxic chemicals such as cyanide in levels that environmental authorities in the West African nation said were above legal limits.

Villagers expressed frustration with seeing dead fish in the river and with the lack of response to their complaints. At the same time, anger grew over other issues they blamed on the company, Bea Mountain Mining Corporation, including homes they said were cracked by concussions from mining explosives and raids of farms by elephants displaced by the blasts.

In 2024, that anger spilled out in a protest in Gogoima and Kinjor villages. Residents asserted that police responded with beatings and tear gas and that three people were killed. Liberia National Police spokesperson Cecelia Clarke called allegations of excessive force “false and misleading.”

Here are takeaways from the investigation.

Mining accounts for more than half of Liberia’s GDP. But weak enforcement is common, with the World Bank citing limited government capacity.

Between July 2021 and December 2022, the most recent period for which figures could be obtained, Bea Mountain exported more than $576 million worth of gold from Liberia. It contributed $37.8 million to government coffers during that time.

This story was reported in collaboration with The Gecko Project, a nonprofit newsroom reporting on environmental issues. The reporting was supported by the Pulitzer Center. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters, and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

A tiny fraction of the profits reach Liberian communities. Over the same 18-month period, Bea Mountain spent $2 million on environmental and social programs for local communities, or 0.35% of its export revenues.

Liberia's government holds a 5% stake in the mining operations.

Over several years, Bea Mountain operated substandard facilities while cyanide, arsenic and copper repeatedly leaked at levels above legal limits. That’s according to reports that were taken down from the site of Liberia’s Environmental Protection Agency but later retrieved, as well as interviews with government officials, experts and former company employees.

The first of four spills documented by the EPA came in the largest mine's first month of full production in 2016. The most recent documented spill was in 2023. The EPA reports also show that Bea Mountain failed to alert regulators promptly after a spill in 2022 and previously blocked government inspectors as they tried to access the company’s laboratory and view results of testing.

The incidents point to failures in corporate responsibility that “can only be described as sustained negligence,” said Mandy Olsgard, a Canadian toxicologist who reviewed the EPA reports.

As spills continued, Bea Mountain withdrew from the Cyanide Management Code, a global standard recommending pollution limits and requiring independent audits.

After one spill in 2022 that Bea Mountain didn't report within 72 hours as required, residents of a downstream village reported scooping up dead fish and thinking it was a “gift from God.” Some later reported illnesses, but no tests were carried out on them to confirm a link to the spill.

While EPA inspectors repeatedly recommended fines after the spills, only one penalty was issued by the regulator, a $99,999 fine in 2018 that was later reduced to $25,000. It was not clear why.

In a written response to questions, the EPA said the spills it documented occurred before the agency’s current leadership took office in 2024. It said it had ordered Bea Mountain to hire an EPA-certified consultant and reinforce the tailings dam — a storage site for mining waste — and that the measures were implemented. It did not say when that occurred.

Under Liberian law, the state can suspend or terminate licenses if a miner doesn’t fulfill its obligations.

In response to the investigation, the country’s recently dismissed minister of mines, Wilmot Paye, said he was “appalled by the harm being done to our country" and that the government was reviewing all concession agreements. The outspoken minister was dismissed in October.

The Bea Mountain-mined gold is sold to Swiss refiner MKS PAMP, which is in the supply chains of some of the world’s largest companies including Nvidia and Apple. The investigation could not confirm what companies ultimately used the gold.

In response to questions, MKS PAMP said it had commissioned an independent assessment of the largest mine, one of five that Bea Mountain operates in Liberia, in early 2025. It said the assessment found no basis to cut ties but identified areas for improvement related to health and safety. A follow-up visit is planned for 2026.

MKS PAMP declined to share the findings, citing confidentiality. It said it would end the relationship if Bea Mountain doesn’t improve.

Bea Mountain is controlled by Murathan Günal through Avesoro Resources. Murathan is the son of Turkish billionaire Mehmet Nazif Günal, whose business interests include the Mapa Group. Avesoro Resources and Mapa Group did not respond to requests for comment.

Bea Mountain is now exploring new gold reserves elsewhere in Liberia.

Aviram reported from London.

Hawa Manubah, a mother of 13, leaves the ruins of her former home, which she says was damaged by concussions from mining explosives, in Gold Camp, Liberia. "We were in the house when we heard the blasting sound-boom, and everyone ran away," she said on July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Residents express their disappointment with the failure of Bea Mountain Mining Corporation to deliver promises such as schools, hospitals and employment, July 11, 2025, in Gbargbo, Liberia. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

An aerial view shows mining waste flowing into a large pond at an inland location east of Grand Cape Mount, not far from the Mano River in Liberia, July 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

Fatama Massaley holds the son of Essah Massaley, who died during a protest in Kinjor, Liberia, July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)

An aerial view shows the Bea Mountain's N'dablama mine site in Gold Camp, Liberia, July 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Misper Apawu)