With the eyes of a nation fixed on the unrest in Minneapolis, the events haven't left local journalists overmatched.

Over the past month, the Minnesota Star Tribune has broken stories, including the identity of the immigration enforcement officer who shot Renee Good, and produced a variety of informative and instructive pieces. Richard Tsong-Taatarii's photo of a prone demonstrator sprayed point-blank with a chemical irritant quickly became a defining image. The ICE actions have changed how the outlet presents the news.

Click to Gallery

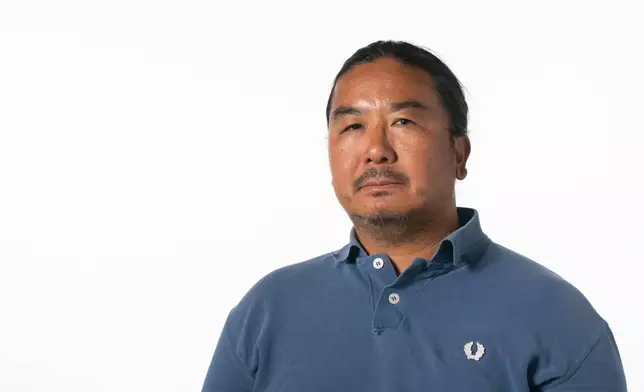

This undated photo shows Star Tribune photographer Richard Tsong-Taatarii in Minneapolis. (Alex Kormann/Star Tribune via AP)

This undated photo shows Star Tribune reporter Liz Sawyer in Minneapolis. (Aaron Lavinsky/Star Tribune via AP)

This undated photo shows Steve Grove, publisher and chief executive of the Star Tribune, speaking to the newsroom in Minneapolis. (Renee Jones Schneider/Star Tribune via AP)

A protester sits on the street with his arms up in front of federal agents in Minneapolis, on Saturday, Jan. 24, 2026. (Alex Kormann/Star Tribune via AP)

At a time when many regional newspapers have become hollowed-out shells due to the decline in journalism as a business, the Star Tribune has kept staffing relatively steady under billionaire Glen Taylor, who has owned it since 2014. It rebranded itself from the Minneapolis Star Tribune and committed itself to a digital transformation.

It was ready for its moment.

“If you hadn't invested in the newsroom, you wouldn't be able to react in that way,” said Steve Grove, publisher and chief executive.

The Star Tribune hasn't operated in a vacuum. Minneapolis has a robust journalism tradition, particularly on public radio and television. Sahan Journal, a digital newsroom focusing on immigrants and diverse communities, has also distinguished itself covering President Donald Trump's immigration efforts and the public response.

“The whole ecosystem is pretty darn good,” said Kathleen Hennessey, senior vice president and editor of the Star Tribune, “and I think people are seeing that now.”

While national outlets have made their presence felt, strong local teams offer advantages in such stories. The Star Tribune's Josie Albertson-Grove was one of the first journalists on the scene after ICU nurse Alex Pretti was shot dead on Jan. 24. She lives about a block away, and her knowledge of the neighborhood and its people helped to reconstruct what happened.

Journalists with kids in school learned about ICE efforts to target areas where children gather by hearing chatter among friends. While covering a beat like public safety can carry baggage, Star Tribune reporter Liz Sawyer developed sources that helped her, along with colleagues Andy Mannix and Sarah Nelson, report on who shot Good.

Besides those contacts, the staff simply knows Minnesota better than outsiders, Hennessey said.

“This is a place with a really, really long and entrenched tradition of activism, and a place with really deep social networks and neighborhood networks,” she said. “People mobilize quickly and passionately, and they're noisy about it. That's definitely been part of the story.”

A Signal chat tipped Tsong-Taatarii about a demonstration growing raucous on Jan. 21. Upon arriving, he focused his lens on one protester knocked to the ground, leaving the photographer perfectly placed for his richly-detailed shot. Two officers hold the man face-down with arms on his back, while a third unleashes a chemical from a canister inches from his face. The bright yellow liquid streams onto his cheek and splatters onto the pavement.

What some have called the sadistic cruelty involved in the episode outraged many who saw the photo. “I was just trying to document and present the evidence and let people decide for themselves,” Tsong-Taatarii said.

In one enterprising story, the Star Tribune's Christopher Magan and Jeff Hargarten identified 240 of an estimated 3,000 immigrants rounded up in Minnesota, finding 80% had felony convictions but nearly all had been through the court system, been punished and were no longer sought by police. Hargarten and Jake Steinberg collaborated on a study of how the size of the federal force compared with that of local police.

Columnist Laura Yuen wrote that her 80-year-old parents have begun carrying their passports when they leave their suburban townhouse, part of the “quiet, pervasive fear” in the Twin Cities. Yuen downloaded her own passport to carry on her phone. “A document that once made me proud of all the places I've traveled is now a badge to prove I belong,” she wrote.

A piece by Kim Hyatt and Louis Krauss detailed the health consequences of chemical irritants used by law enforcement — or thought to be used, since questions about what specifically was deployed went unanswered.

“I really think they've done a commendable job,” said Scott Libin, a veteran television newsman and journalism professor at the University of Minnesota. He praised the Star Tribune's story about the criminal backgrounds of immigrants as thorough and dispassionate.

Since Hennessey, a former Associated Press editor, began her job last May, the Star Tribune has experienced a run of big stories, including the shooting of two state lawmakers and a gunman opening fire at a Catholic school in Minneapolis. And, of course, “we have a newsroom that still has muscle memory from George Floyd ” in 2020, Grove said.

News compelled fundamental shifts in the way the Star Tribune operates. Like some national outlets, it has rearranged staff to cover the story aggressively through a continuously updated live blog on its website, offered free to readers. There's also a greater emphasis on video, with the Star Tribune doing forensic studies on footage from the Pretti and Good shootings, something few local newsrooms are equipped to do. Traffic to its website has gone up 50 percent, paid subscriptions have increased and the company is getting thousands of dollars in donations from across the country, Grove said.

“People have changed the way that they consume news,” Hennessey said. “We see that readers are coming back. You know, they're not just waking up in the morning, reading the site and then forgetting about us all day long. They're coming back a couple of times a day to check in on what's new.”

Most people in the newsroom are contributing to the story, including the Star Tribune’s food and culture team, and its outdoor reporters. “There are no normal beats anymore,” Albertson-Grove said.

Under Grove, a former Google executive, the Star Tribune has attempted a digital-first transition, turning over about 20% of its staff in two years. The paper shut its Minneapolis printing plant in December, laying off 125 people, and moving print operations to Iowa.

“We face every single headwind that every local news organization in the country does,” Grove said. “But we do feel fortunate that we're the largest newsroom in the Midwest and it's part of the reason we're able to do this now.”

As a reporter, Sawyer says the public response to the outlet's work, sharing stories and images, has lifted her spirits. Readers see it as public service journalism. Still, she could use a break. She and her husband, Star Tribune photographer Aaron Lavinsky, have a baby daughter and make sure to stagger their coverage. They can't both be tear-gassed or arrested at the same time; who makes the daycare pickup?

“I think both residents and journalists in this town are running on fumes,” she said. “We're tired of being in the international spotlight and it's never for something positive. People are trying their best to get through this moment with grace.”

David Bauder writes about the intersection of media and entertainment for the AP. Follow him at http://x.com/dbauder and https://bsky.app/profile/dbauder.bsky.social.

This undated photo shows Star Tribune photographer Richard Tsong-Taatarii in Minneapolis. (Alex Kormann/Star Tribune via AP)

This undated photo shows Star Tribune reporter Liz Sawyer in Minneapolis. (Aaron Lavinsky/Star Tribune via AP)

This undated photo shows Steve Grove, publisher and chief executive of the Star Tribune, speaking to the newsroom in Minneapolis. (Renee Jones Schneider/Star Tribune via AP)

A protester sits on the street with his arms up in front of federal agents in Minneapolis, on Saturday, Jan. 24, 2026. (Alex Kormann/Star Tribune via AP)

NEW YORK (AP) — Once considered an oddity in American homes, bidets are becoming increasingly common as more people seek a hygienic and sustainable alternative to toilet paper or a hand managing certain physical conditions.

Toilet paper shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic helped demystify the devices for U.S. consumers, although Italy, Japan and some other countries where bidets are standard bathroom features also saw runs on TP. Environmental awareness, less expensive bidet options and the development of smart toilets that perform multiple functions have given further momentum to the idea of rinsing instead of wiping.

Bidets even earned a moment in the national spotlight last month when Zorhan Mamdani, New York City's new mayor, said he hoped to have them installed in the bathrooms of Gracie Mansion, the 18th century Manhattan home that serves as the official residence of the city's chief executive.

Medical professionals sometimes recommend bidets for patients with hemorrhoids, in recovery from surgery, or who have limited mobility due to age or disabilities. But experts say bidets are not best for everyone and need to be used properly to prevent other problems.

Here are some of the ins and outs to consider.

Bidets use a jet of water to clean the genitals and anal area after someone goes to the bathroom. They originally existed mainly as standalone fixtures separate from toilets.

These days, the options include toilet seat attachments and hand-held versions that resemble detachable shower heads. Many of the latest “smart” toilets come with integrated bidets and feature heated seats, adjustable water pressure and air dryers.

On YouTube and other social media platforms, there are videos demonstrations of how to make a portable bidet with a plastic soda bottle.

Bidet converts tend to rave about how much cleaner the appliances leave them feeling. Since all toileting activity involves delicate body parts and bacteria, experts stress that correct bidet use is required to make the activity as sanitary as possible.

When using standalone bidets and ones installed on toilets, it's best, especially for women, to turn on the faucet while facing the controls so the washing is done from front to back, according to Dr. David Rivadeneira, a colorectal surgeon in Huntington, New York.

That position prevents the transfer of bacteria from the anal area to the urethra, Rivadeneira said.

Most doctors recommend using warm water at low pressure for up to a few minutes, avoiding any extreme temperatures. You can also try a gentle soap if desired, but it's usually not necessary for regular bidet users.

Rivadeneira cautions patients against trying to inject water into the anus since the devices are not meant for internal use.

“You're not supposed to be substituting it for a colonic or an enema," he said.

After washing, pat dry with toilet paper or a dedicated cotton towel to remove any remaining stool and to prevent yeast infections, experts say.

Bidets can be used every day but are most appropriate after a bowel movement. Overuse may cause skin irritation, according to medical experts.

Proper bidet maintenance also matters, said Dr. Neal H. Patel, a family physician with the Providence St. Joseph Hospital in Orange County, California. Make sure to wipe down the nozzle every week or two with disinfectant wipes to remove bacteria, he said.

Dr. Danielle Antosh, a urogynecologist in Houston, said some studies have showed that a bidet leaves less bacteria on a user's hand compared to toilet paper, but the research remains too limited to know for sure.

However, doctors who are in favor of bidets think the devices are less harsh on sensitive skin than toilet paper.

“The texture of toilet paper can cause irritation and itching, while the gentle water stream of a bidet is less abrasive and healthier for the skin,” Dr. George Ellis, a urologist in Orlando, Florida, said.

Bidets therefore may benefit people with chronic diarrhea or other conditions that necessitate a lot of wiping, as well as those who are prone to urinary tract infections, medical experts said. They also may help relieve discomfort from hemorrhoids, fistulas and anal fissures, they said.

Three dermatologists from the University of Tennessee Health Science Center wrote in a 2023 editorial in the International Journal of Women's Dermatology that their peers should be “aware of the commonality of bidet use outside of American culture” and comfortable recommending bidets because skin conditions such as eczema, psoriasis and contact dermatitis can occur in the perianal region.

They also argued that by helping people with physical limitations clean themselves independently after using the toilet, bidets can reduce the workload of caregivers, most of whom are women.

Bidets are another example where it's possible to get too much of a good thing. Some doctors in Japan have advised patients who reported rashes or difficulty controlling their bowels after frequent bottom cleansing to stop using bidets until the conditions cleared up.

Antosh recommends checking with a doctor before using a high-pressure bidet right after childbirth or if you have genital ulcers because powerful streams of water may be irritating.

Dr. Jenna Queller, a dermatologist and founder of Boca Raton, Florida-based DermWorks, said the same was true for people with genital eczema or psoriasis. She recommends moisturizing the areas after using a bidet to prevent irritation..

And while bidets may offer relief for an itchy bottom, always consult a doctor if there's persistent bleeding from fissures or hemorrhoids because you could have a more serious condition, Rivadeneira advises.

Bidets generally are recognized as a greener choice than toilet paper by most environmental groups and scientists. The non-profit National Resources Defense Council said in a recent report that the devices “significantly cut down on the use of toilet paper, helping to lessen the environmental impacts associated with tissue production.”

Gary Bull, a professor emeritus of forestry at the University of British Columbia told The Associated Press in a recent interview that while it makes sense and is agreed bidets are more sustainable, truly knowing the environmental impact of a product requires calculating all the carbon emitted and energy used in making the products and through the end of their life cycles.

Fancier bidets, for example, use electricity to heat the water and seat, he noted.

“I was working out in my own house last night putting in a Japanese bidet because I just came back from Japan, and I went, ‘OK, so this is good,’” Bull said. “But then if I look at that bidet, if I’m doing an honest assessment cradle to cradle, then I have to look at the water consumption, the energy consumption, a whole bunch of other things, to know whether or not that is a better choice for me as a consumer versus toilet tissue.”

Andrea Hicks, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Wisconsin, suggested thinking about how dry or wet a climate you live in before making a decision.

In a “water-stressed” state like Arizona, toilet paper may be the more sustainable choice, while a bidet might more sense in a place where water is abundant, Hicks said.

——-

AP Writer Isabella O’Malley in Philadelphia contributed to this report.

FILE - A smart bidet sits in a bathroom at the McKechnie Family LIFE Home on the University Illinois campus in Champaign, Ill., Thursday, Dec. 9, 2021. (Robin Scholz/The News-Gazette via AP, File)