In some ways, the goals Canadian snowboarder Mark McMorris set for the Milan Cortina Olympics are the same ones he set in his three previous appearances at the Games.

“Landing when it matters, landing how I want to, landing my hardest tricks and walking away with some hardware,” he said.

But this time, McMorris listed one other element that no Olympian on the ground four years ago in China will ever take for granted again: “To enjoy it with my friends.”

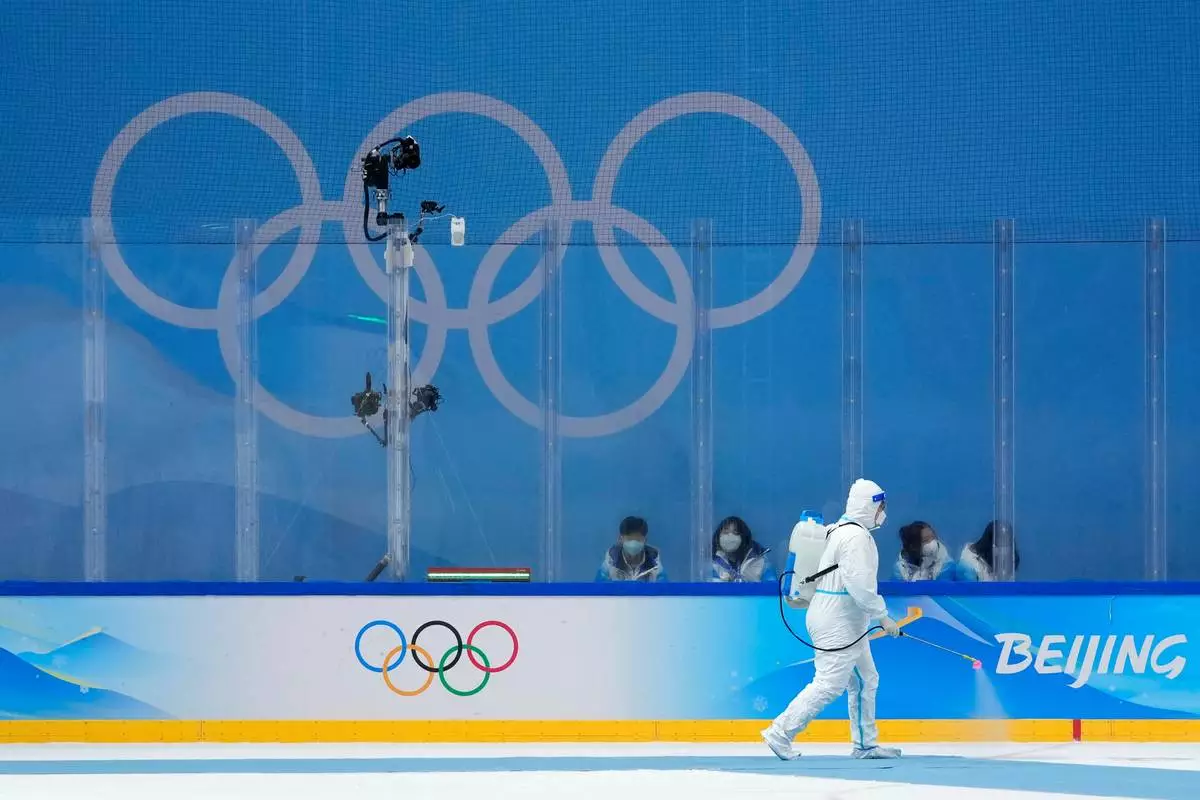

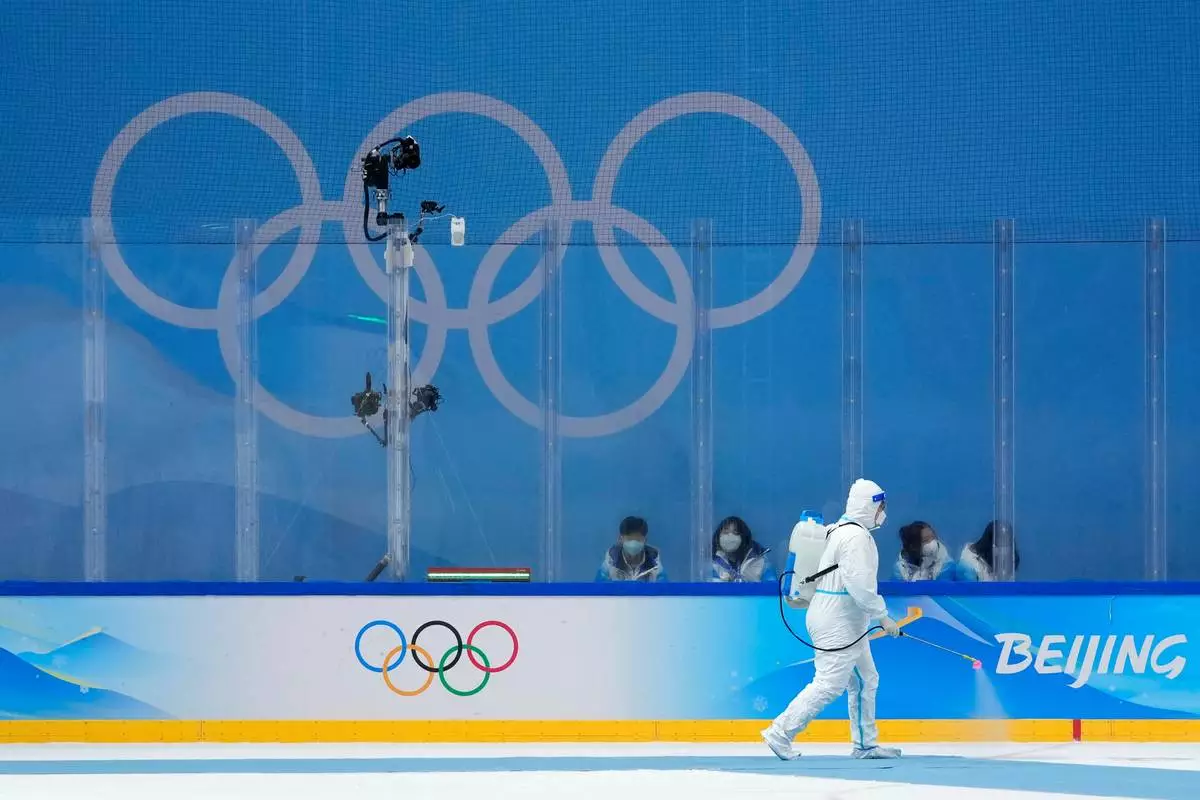

The last time the Winter Olympians convened, the COVID-19 pandemic was still raging. The Games were forced into sterilized bubbles with athletes facing daily tests; in most cases, at checkpoints where workers stuck swabs up their noses. Every swab brought with it the specter of a positive test, with could mean days or weeks of quarantine that would wipe out an athlete's ability to compete.

McMorris, the 32-year-old slopestyler who won his third straight bronze medal at those Games, summed up the experience by famously calling his stay in the mountains something like a trip to “sports prison."

“What I can tell you with absolute certainty is that I am really excited to compete in this Games without COVID tests every 24 hours and just the pandemic breathing down our necks,” said Mikaela Shiffrin, who went without a medal in Beijing. “It’s a very, very different situation to go into this Games and that’s a wonderful thing.”

Short track speedskater Andrew Heo, whose first Olympics were in Beijing, said getting back to a “real, live Games” was one of his biggest motivators over the past four years.

“The Beijing Olympics was cool in itself, because I didn’t have any prior experience,” Heo said. “But so many people told me: This is like nothing compared to what an actual Olympics is like.”

The contrasts will be everywhere. McMorris and the rest of the action-sports athletes will be in Livigno, one of a handful of Alps resort towns joining Milan in hosting an Olympics that will look and feel nothing like the Beijing Games.

As much as the good wine, good food and not having to eat behind a plastic shield at restaurants, McMorris said he's simply glad to have the people who have backed him for years along for the ride. Olympians in China told of getting to the starting line but feeling lost without the backing of friends and family, the support systems that drive so much of their day-to-day lives in sports.

“Hopefully I can use their support to fuel myself. It will be good to enjoy the Olympics as a crew this time,” McMorris said.

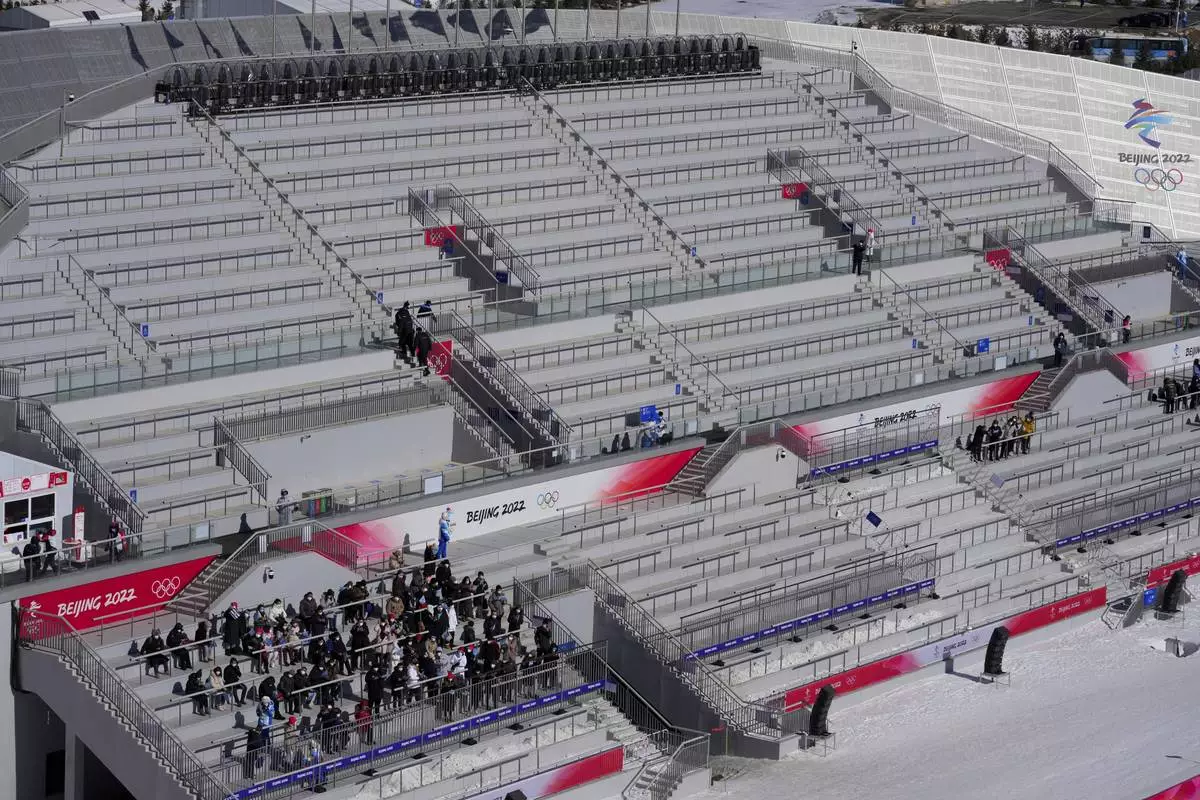

For the general public, some of the novelty of a “normal” Olympics has worn off. The well-received, well-attended and well-viewed Summer Games in Paris two years ago marked something of a rebirth of an Olympic brand that was stagnating even before COVID wrapped the Tokyo Summer Games and then Beijing in something resembling a germ-free bubble.

The direness of those Olympics might have been best illustrated by Belgian skeleton rider Kim Meylemans, whose desperate plea for release from quarantine, days after a positive test, went viral four years ago in China.

Even those not under quarantine were jarred by the less-than-welcoming feel as they got off the airplane.

"Instead of having, like, a cheering welcome committee, we’re like funneled in to get a cotton swab stuck up our nose and down our throat for a COVID test,” two-time bronze-medal-winning U.S. speedskater Brittany Bowe said. “Every single morning it’s like, you’re in line to go get your COVID test and just hoping and praying like you are not one that’s going to have a positive test.”

The U.S. sled hockey team aiming for a third consecutive Paralympic gold medal has several players whose only experience at this stage came in the Beijing bubble. For some, the return to normal cuts both ways.

"We’ll definitely chat about kind of managing how much time you can spend with your family: Don’t want to give any of them the impression that you can just hang out with them all the time, in all your free time, because you need that recharge personal time, as well,” veteran forward Declan Farmer said. “Just be prepared for that, a little bit of added pressure of having them in attendance.”

For many, though, that is a small price to pay.

Caroline Harvey's only Olympics came four years ago when she and the U.S. women's hockey team lost to Canada in the final. The Americans are favorites this time, a status that brings with it the tantalizing prospect of a victory showered with cheers instead of the stunned silence of four years earlier.

“Really looking forward to having family there, friends, having some of that comfort and familiarity within such a stressful obviously environment,” Harvey said.

AP National Writer Howard Fendrich contributed to this report.

AP Olympics: https://apnews.com/hub/milan-cortina-2026-winter-olympics

FILE - A worker wearing a protective suit disinfects the arena after the women's gold medal hockey game between Canada and the United States at the 2022 Winter Olympics, Feb. 17, 2022, in Beijing. (AP Photo/Petr David Josek, File)

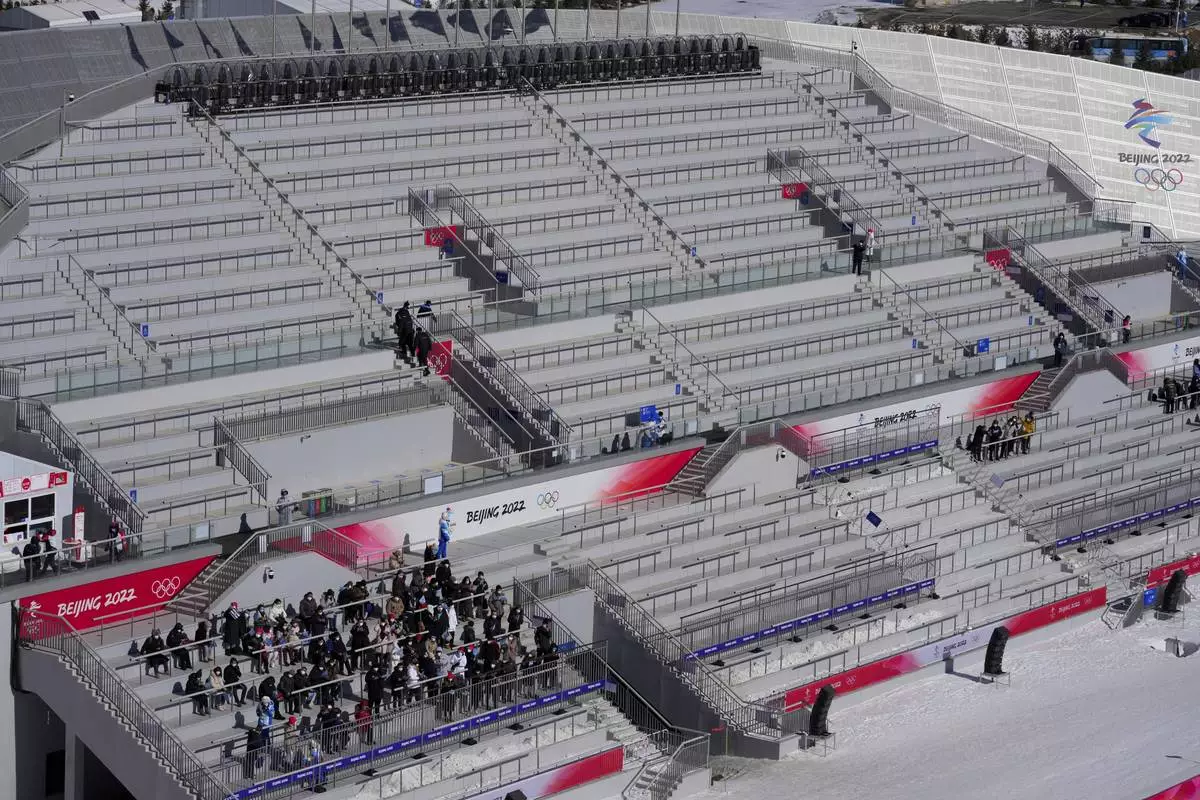

FILE- People watch the men's normal hill individual ski jumping trial round in a nearly empty Zhangjiakou National Ski Jumping Centre at the 2022 Winter Olympics, Feb. 5, 2022, in Zhangjiakou, China. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini, File)

MILAN (AP) — Norwegian skier Nikolai Schirmer on Wednesday handed the International Olympic Committee a petition signed by more than 21,000 people and professional athletes who want to stop fossil fuel companies from sponsoring winter sports.

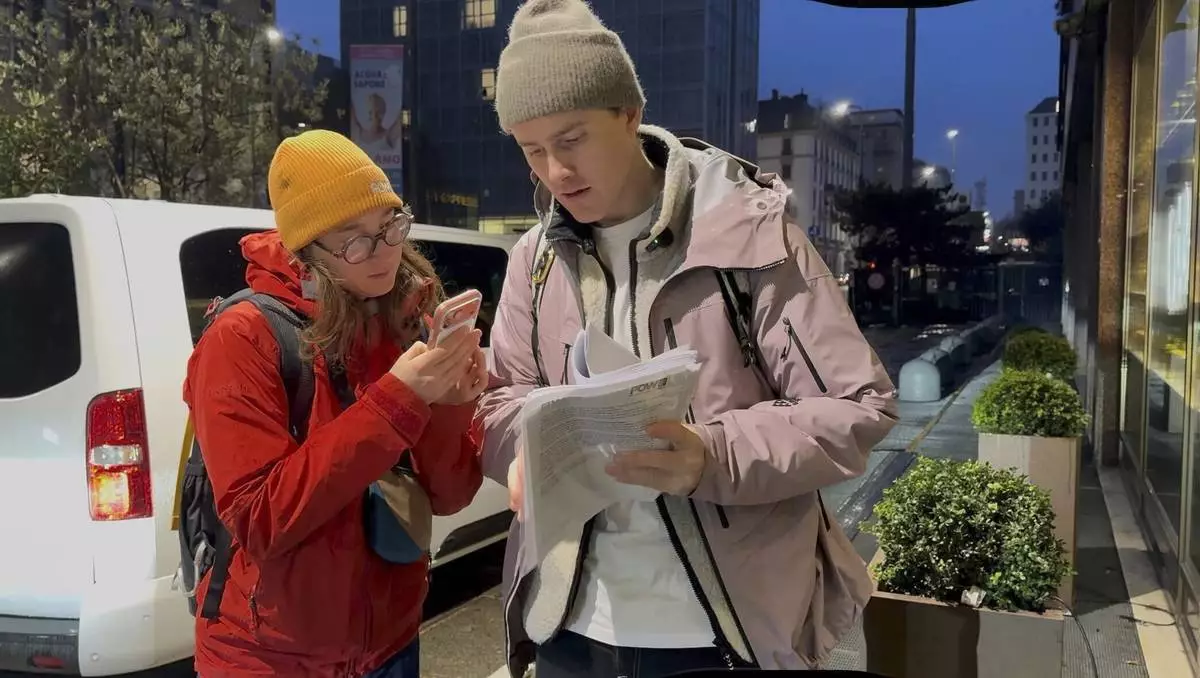

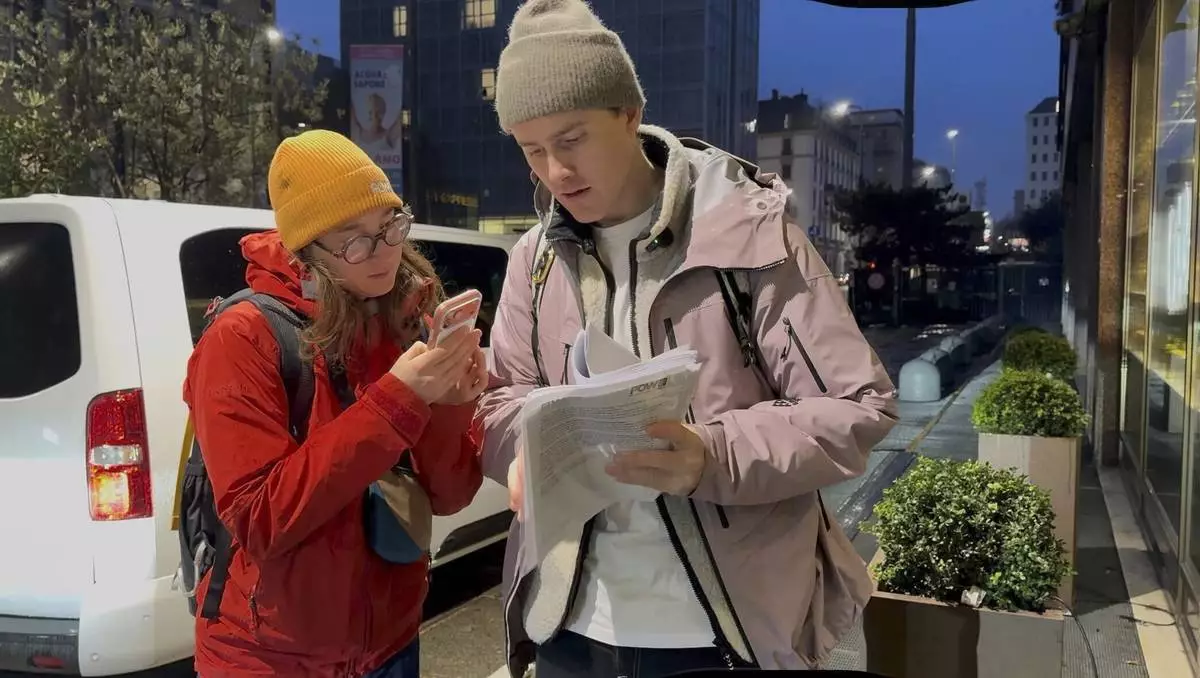

Schirmer delivered the “Ski Fossil Free” petition to the IOC's head of sustainability, Julie Duffus, at a hotel in the Italian city of Milan two days before the Milan Cortina Winter Olympics kick off.

The petition asks the IOC and the International Ski and Snowboard Federation, FIS, to publish a report evaluating the appropriateness of fossil fuel marketing before next season. Schirmer, a filmmaker and two-time European Skier of the Year, spoke exclusively with The Associated Press outside the hotel, and said the IOC informed him that it would not allow media to witness their meeting.

“It seems like the Olympics aren’t ready to be the positive force for change that they have the potential to be,” Schirmer told the AP afterward. “So I just hope this can be a little nudge in the right direction, but we will see.”

Schirmer is a freeride skier who documents his adventures exploring Europe’s steep terrains. While freeride skiing is not currently an Olympic event, he said he felt like he needed to bring attention to fossil fuel marketing.

“The show goes on while the things you depend on to do your job — winter — is disappearing in front of your very eyes,” he said. “Not dealing with the climate crisis and not having skiing be a force for change just felt insane. We’re on the front lines.”

Burning fossil fuels – coal, oil and gas – is the largest contributor to global climate change by far. As the Earth warms at a record rate, winters are shorter and milder and there is less snow globally, creating clear challenges for winter sports that depend on cold, snowy conditions. Researchers say the list of locales that could reliably host a Winter Games will shrink substantially in the coming years.

Schirmer launched his petition drive in January. He surpassed his goal of 20,000 signatures in one month, and people continue to sign.

It's a first step, he argues, much like a campaign nearly 40 years ago that led to a ban of tobacco advertising at the Games. United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres has urged every country to ban advertising from fossil fuel companies.

In his meeting on Wednesday, Schirmer said, the IOC's head of sustainability pointed to the organization's commitments to renewable energy. He said he feels that isn't enough.

The IOC told the AP in a statement that climate change is one of the most significant challenges facing sport and society. It didn’t say whether it will review fossil fuel marketing, as demanded by the petition.

Olympic partners play an important role in supporting the Games, and they include those investing in clean energy, the statement said.

FIS welcomes mobilization campaigns like this one, spokesperson Bruno Sassi said. He noted that He noted that no fossil fuel companies are partners of the FIS World Cup and FIS World Championships.

Athlete-driven environmental group “Protect Our Winters” supported the petition drive. This is the first coordinated campaign about fossil fuel advertising centered around an Olympic Games, POW's CEO Erin Sprague told the AP.

American cross-country skier and Team USA member Gus Schumacher said he signed because it starts the conversation.

“It’s short-sighted for teams and events to take money from these companies in exchange for helping them hold status as good, long-term energy producers,” he wrote in a text message.

American cross-country skier Jack Berry said he’s hopeful this is an influential step toward a systemic shift away from the industry. Berry is seeking a spot on Team USA for the Paralympics in March.

Italy's Eni, one of the world’s seven supermajor oil companies, is a “premium partner” of these Winter Games. Other oil and gas companies sponsor Olympic teams.

Eni said it's strongly committed to the energy transition, as evidenced by how it's growing its lower carbon businesses, reducing emissions and aiming for carbon neutrality by 2050. And the company defended its role in the Winter Games.

“Through the partnership with the biggest event hosted by Italy in the next 20 years, Eni wants to confirm its commitment to the future of the country and to a progressively more sustainable energy system through a fair transition path,” spokesperson Roberto Albini wrote in an e-mail.

A January report found that promoting polluting companies at the Olympics will grow their businesses and lead to more greenhouse gas emissions that warm the planet and melt snow cover and glacier ice. Albini disputed the emissions calculations for Eni in the Olympics Torched report.

Published by the New Weather Institute in collaboration with Scientists for Global Responsibility and Champions for Earth, the report also looks at the Games' own emissions.

“They have lots of sponsors that aren't in these sectors,” said Stuart Parkinson, executive director at Scientists for Global Responsibility. “You can get the sponsorship money you're after by focusing on those areas, much lower carbon areas. That reduces the carbon footprint.”

McDermott reported from Cortina D’Ampezzo, Italy.

AP Olympics: https://apnews.com/hub/milan-cortina-2026-winter-olympics

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Winner Johannes Hoesflot Klaebo of Norway, centre, second placed Gus Schumacher of United States, left, and Edvin Anger of Sweden, right, celebrate on the podium after the men's sprint final classic skiing race, during the FIS Cross-Country World Cup at the Nordic Center Goms, in Geschinen, Switzerland, Saturday, Jan. 24, 2026. (Salvatore Di Nolfi/Keystone via AP)

Workers set up fencing along the slopestyle course before a training session at the 2026 Winter Olympics, in Livigno, Italy, Wednesday, Feb. 4, 2026. (AP Photo/Gregory Bull)

FILE - United States' Shaun White trains before the men's halfpipe finals at the 2022 Winter Olympics, Feb. 11, 2022, in Zhangjiakou, China. (AP Photo/Gregory Bull, File)

Norwegian skier Nikolai Schirmer walks out of a Milan hotel, Wednesday, Feb. 4, 2026, after privately meeting with the IOC's head of sustainability, Julie Duffus, to hand her a “ski fossil free” petition with over 20,000 signatures two days before the Opening Ceremony for the 2026 Milan Cortina Winter Olympics. (AP Photo/Fernanda Figueroa)

Norwegian skier Nikolai Schirmer and Protect Our Winters Italy General Manager Giorgio Garancini look over a “ski fossil free” petition with over 20,000 signatures that Schirmer privately handed to the IOC's head of sustainability, Julie Duffus, two days before the Opening Ceremony for the 2026 Milan Cortina Winter Olympics, Wednesday, Feb. 4, 2026, in Milan. (AP Photo/Fernanda Figueroa)