WASHINGTON (AP) — Secretary of State Marco Rubio is leading a large U.S. delegation this week to the Munich Security Conference where increasingly nervous European leaders are hoping for at least a brief reprieve from President Donald Trump’s often inconsistent policies and threats that have roiled transatlantic relations and the post-World War II international order.

A year after Vice President JD Vance stunned assembled dignitaries at the same venue with a verbal assault on many of America’s closest allies in Europe, accusing them of imperiling Western civilization with left-leaning domestic programs and not taking responsibility for their own defense, Rubio plans to take a less contentious but philosophically similar approach when he addresses the annual gathering of world leaders and national security officials Saturday, U.S. officials say.

The State Department’s formal announcement of Rubio’s trip offered no details about his two-day stop in Munich, after which he will visit Slovakia and Hungary. But the officials, who spoke on condition of anonymity to preview the trip, said America's top diplomat intends to focus on areas of cooperation on shared global and regional concerns, including in the Middle East and Ukraine as well as China, an economic powerhouse seeking to take advantage of the uncertainty in U.S.-European ties.

Should that be the case, many in the audience may be relieved after being buffeted first by Vance’s blunt rebukes last year and then a series of Trump statements and moves in the months since that have targeted virtually every country in Europe, Canada and long-standing allies in the Indo-Pacific.

Trump’s recent comments about taking control of Greenland from NATO member Denmark and insults hurled at various leaders were particularly unnerving, leading many in Europe to question the value of the U.S. as an ally and partner.

That leaves Rubio with a heavy lift if he wants to calm the waters.

Vance's speech last year was “really a shock moment,” said Claudia Major, a senior vice president at the German Marshall Fund in Berlin. “It was perceived as the first very clear statement of what the new Trump administration was about," namely that “Europeans are not partners any longer.”

“There is a big doubt whether the basis (of trust) is still there and whether we still share the same vision for the trans-Atlantic relationship,” she said. “The longer this kind of estrangement goes, the more difficult it will be to re-find a solid relationship.”

Munich Security Conference chairman Wolfgang Ischinger offered a similar view.

“Transatlantic relations are currently in a significant crisis of confidence and credibility,” he said this week. But he also expressed hope that Rubio and the dozens of U.S. lawmakers expected to attend the meeting will offer a less dire and dour prognosis for the future.

German Chancellor Friedrich Merz, whom Rubio will meet Friday, has tried to adopt a middle line to deal with Trump’s unpredictability and insistence on transactional relations.

He said Europe also needs to “learn the language of power politics” to assert itself, for example, by taking greater responsibility for its security, striving for greater “technological independence” and boosting its economic growth. But he stressed that “as democracies, we are partners and allies and not subordinates” of the U.S.

Some, like French President Emmanuel Macron and Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney, appear to have all but given up on Trump and the United States. Both Canada and France opened consulates in the Greenlandic capital, Nuuk, last week in a show of support for both Greenland and Denmark.

Macron warned this week that tensions between Europe and the U.S. could intensify after the recent “Greenland moment.” He described the Trump administration as “openly anti-European” and seeking the European Union’s “dismemberment."

“When there’s a clear act of aggression, I think what we should do isn’t bow down or try to reach a settlement,” he said in an interview with several European newspapers. “I think we’ve tried that strategy for months. It’s not working.”

Macron noted a “double crisis: We have the Chinese tsunami on the trade front, and we have minute-by-minute instability on the American side.”

Carney — who drew applause from many for pushing back against Trump in a speech last month at the World Economic Forum meeting in Davos, Switzerland — has made no secret of his frustration and impatience with the Republican president.

Carney has emerged as a leader of a movement for countries to find ways to link up and counter the U.S. He vowed to pursue trade deals with countries other than the U.S., including China, to serve as anchors of commercial stability. The China deal drew new threats from Trump.

For many in Europe, Trump’s intentions regarding Greenland exacerbate their fears over Russia’s war with Ukraine and serve as a reminder of centuries of power politics in which diplomacy was subordinate to the use of military force.

“Greenland is to Trump as, essentially, Ukraine is to (Russian President Vladimir) Putin, although obviously without the devastating war at this stage,” said Fiona Hill, a Russia expert who served on the White House National Security Council during Trump’s first term in office.

In the meantime, as Trump tries to mediate an end to the Russia-Ukraine war and seek a nuclear deal with Iran, Europeans are increasingly uneasy about Trump’s “Board of Peace,” a 27-member group of world leaders tasked first with handling the Gaza peace agreement but eventually envisaged as a vehicle for resolving other major conflicts.

Germany, France, Britain, Italy, Norway and Sweden, among others, have either declined to accept or have not yet signed on to the board, which will hold its first meeting to raise money for Gaza in Washington on Feb. 19.

Associated Press writers Emma Burrows in London, Geir Moulson in Berlin and Lorne Cook in Brussels contributed to this report.

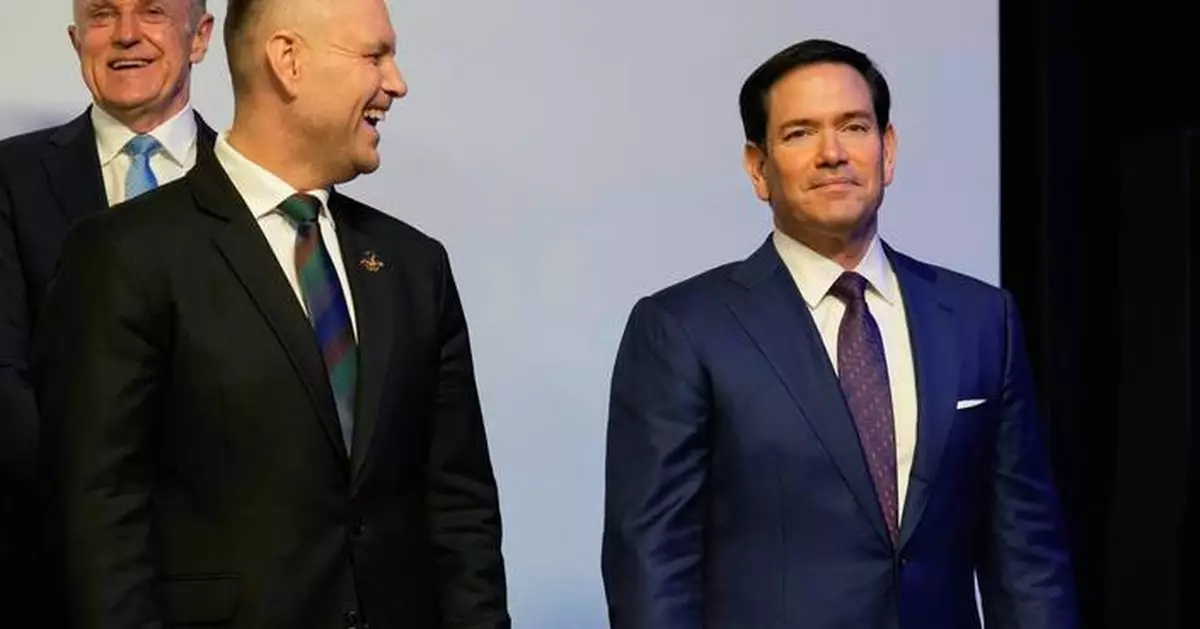

U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio, right, looks on ahead of a group photo at the Heads of states dinner, at the 2026 Winter Olympics, in Milan, Italy, Thursday, Feb. 5, 2026. (AP Photo/Luca Bruno, Pool)

BANGKOK (AP) — One recent night, Youga was grateful when he finally slept in a bed, even though it had neither pillow nor blanket.

For two days, the African man said, he slept on the street after he reached Cambodia's capital, Phnom Penh, following his escape from a scam compound in O'Smach, which borders Thailand in the north. He had only $100 left to his name and wanted to save the money. So the Caritas shelter took him in.

The shelter, the only one of its kind that helps victims escaping from scam compounds, was funded previously by the United States. Today, it is stretched at the seams, working with a third of the staff and a fraction of the budget it previously had as the country faces an unprecedented surge of workers leaving scam compounds.

Now, overwhelmed, the shelter has had to turn away people in need, more than 300 of them. Mark Taylor, who works on human trafficking issues in Cambodia, said, “It's become triage.”

As of last week, the shelter had about 150 people. Many of the newest arrivals were sleeping in a common room and didn’t have more than the clothes on their backs. The shelter didn’t have enough pillows and blankets, said Youga, who spoke on condition that only his first name be used out of fear of his former bosses.

Cambodia is facing an unprecedented flood of workers leaving scam compounds. It comes weeks after the country extradited a suspected kingpin of the scam business who had played a prominent role in Cambodian society to China in January.

In recent years, online-based scams have become endemic to the region in Cambodia, Myanmar, and Laos. Inside these buildings, scammers have built sophisticated operations, utilizing phone booths lined with foam for soundproofing, scripts in multiple languages, and even fake police booths of countries ranging from Brazil to China. In Cambodia, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights estimated that there were up to 100,000 workers alone in 2023.

After growing international pressure from countries like South Korea, the U.S. and China built up over the past several months, Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Manet announced last month that “combating crime is a deliberate political priority” and specifically named cyberfraud. The Cambodian government said it deported 1,620 foreign nationals from 21 countries linked to scam operations in January.

Compounds have been letting people go en masse in recent days, according to 15 videos and images on social media verified by Amnesty International. The organization also interviewed 35 victims, who described a “chaotic and dangerous” situation in trying to leave, although many noted a lack of involvement from Cambodian authorities in the mass exodus.

The departures from scamming compounds have created a humanitarian crisis on the streets that, activists say, is being ignored by the Cambodian government. In scenes of chaos and suffering, thousands of traumatized survivors are being left to fend for themselves with no state support,” Montse Ferrer, regional research director for Amnesty International, said in a statement.

“The Royal Government of Cambodia rejects claims that it is failing trafficking victims or tolerating abuse linked to scam compounds,” said Neth Pheaktra, Minister of Information Cambodia in response to the claims. “All individuals are screened to separate victims from perpetrators, with victims receiving protection, shelter, medical care, and assistance for safe return.”

Li Ling, a rescuer, said she had a list of 223 people, mostly from Uganda and Kenya who had come out from compounds in Cambodia asking for help to get home. She and her partner had spent at least $1000 of their own money to shelter some of the most desperate cases, but cannot sustain that beyond another week.

As of last week, some had gone back to work in the compounds, she added. It was that or face sleeping on the streets.

“When international organizations based in Cambodia are continuing to tell victims to go to their embassies, but the embassies tell us frankly, they don’t have a clear path or process, the responsibility is being shoved back and forth, creating a closed loop with no exit,” she said. “This is not a one-off failure, but a systemic breakdown.”

Those victims waited for hours outside the Phnom Penh office of the International Organization for Migration, a U.N. agency, she said, but were told the Caritas shelter, which IOM works, with is full.

Youga, from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, said he was beaten often while inside a compound because he refused to work. He was determined to get out and escaped on his own as the mass releases began.

The Associated Press was not able to independently verify all of his journey but saw messages of his pleas for help to IOM. The agency said they could not comment on individual cases.

While the shelter is still operating, of most immediate concern in the coming weeks is the budget for food, Taylor said. “It’s hand to mouth.”

The Caritas shelter received financial support from Winrock International, USAID’s partner in Cambodia, according to Taylor who oversaw the funding. It was due to receive $1.4 million from USAID from September 2023 through the first part of 2026. That source of funding went away after U.S. foreign assistance was suspended and USAID was dismantled in early 2025.

The shelter was also partially funded by IOM, which was largely funded by the U.S. and has also seen its funding cut.

Although many anti-trafficking organizations are registered in Cambodia, the Caritas shelter is the only one who takes in victims of scam compounds in an increasingly repressive environment. Under government pressure, independent media have shut down and a prominent journalist known for reporting on scam compounds was arrested and detained for a month.

“Given the deeply repressive environment in Cambodia that emerges from the scam industry's role as a dominant source of ruling party elite rent seeking, there are an extremely small number of formal organizations willing to respond to the issue on the ground," said Jacob Daniel Sims, a visiting fellow at the Harvard University Asia Center who has worked in countertrafficking in Cambodia.

Rescuers say many who do not make it to the shelter can end up in immigration detention, stuck and pushed for bribes from officials. Others are now booking hotel rooms in groups if they have the funds. Those with embassies in the country are able to get help, such as Indonesians or Filipinos.

Youga cannot return home. He is from the Banyamulenge ethnic group, which has been the target of attacks by armed groups. Nor does he have an embassy in the region that can assist him.

He was lured into a scam compound in Cambodia in November after his family sent him to neighboring Burundi. He said he wasn't looking for a job, but someone he didn't know messaged him on his phone and then emailed him about a job, all expenses paid. He said no, but the recruiter still went ahead.

Youga said he was a university student before and wanted to continue. For now, he only hopes for a safe place. “I want," he said, "to rebuild my life with dignity.”

FILE - South Koreans, walking in the line at center, who are allegedly involved in online scams in Cambodia, arrive at the Incheon International Airport in Incheon, South Korea, Jan. 23, 2026. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon, File)

FILE - A Thai soldier inspects a work station with wooden phone booths lined with foam for soundproofing, inside a scam compound in O'Smach, Cambodia, Monday, Feb. 2, 2026. (AP Photo/Sakchai Lalit, File)

FILE - A Thai soldier keeps guard outside a scam center in O'Smach, Cambodia, Monday, Feb. 2, 2026, (AP Photo/Sakchai Lalit, File)

Youga stands at an undisclosed location in Cambodia, on Jan. 22, 2026. (AP Photo)