KITENGELA, Kenya (AP) — At a special school in Kenya, the classrooms look like few others. Instead of standing and lecturing at Rare Gem Talent School, teachers use hands-on lessons focused on sights, sounds, and feelings designed for a unique type of learner: students with dyslexia.

Despite increasing access to public education in Kenya, students with learning disabilities are frequently left behind. Requiring only tweaks to core curriculums, Rare Gem is one of a handful of schools in the country tailored to children with dyslexia and other learning challenges.

Click to Gallery

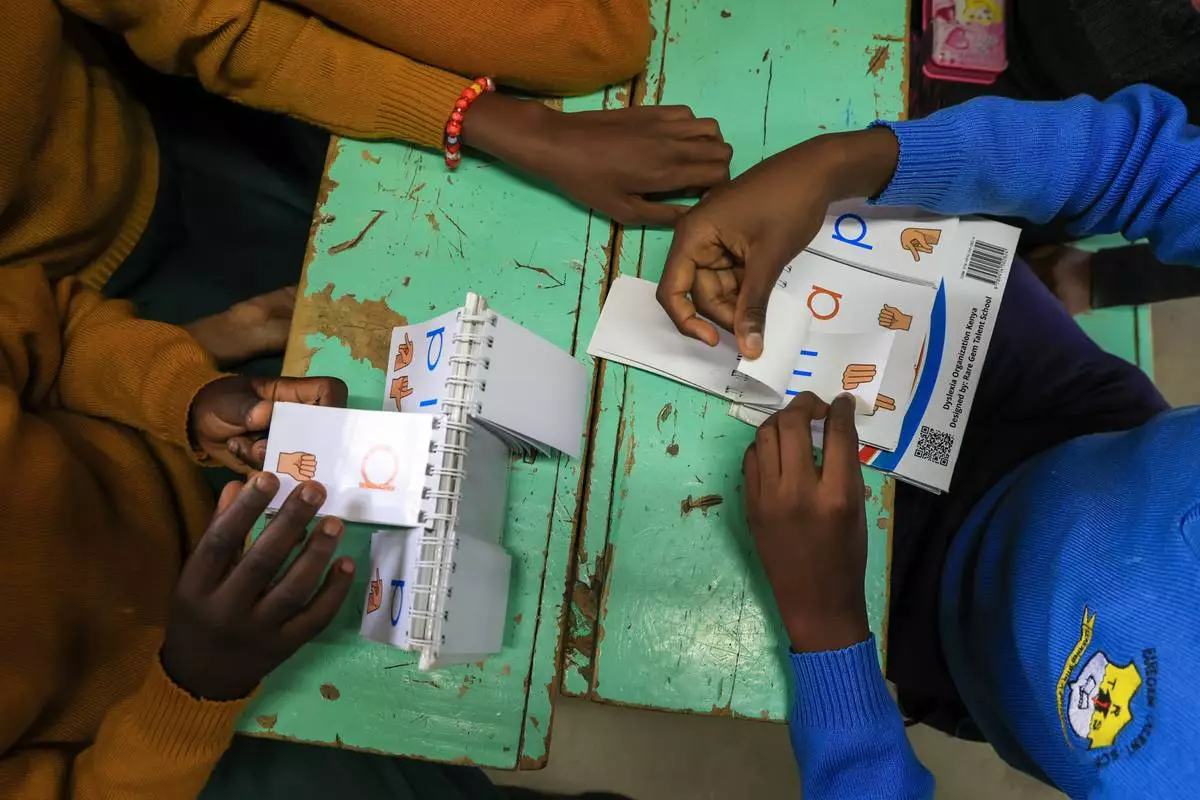

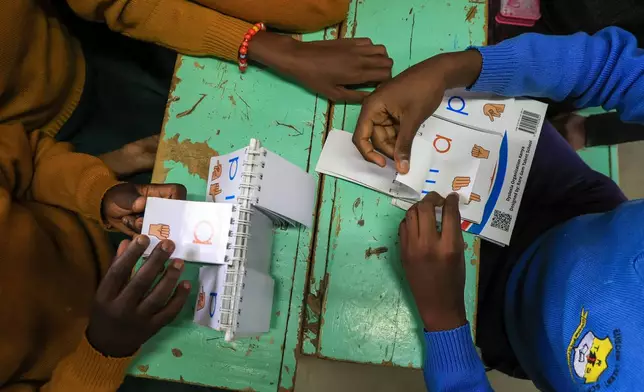

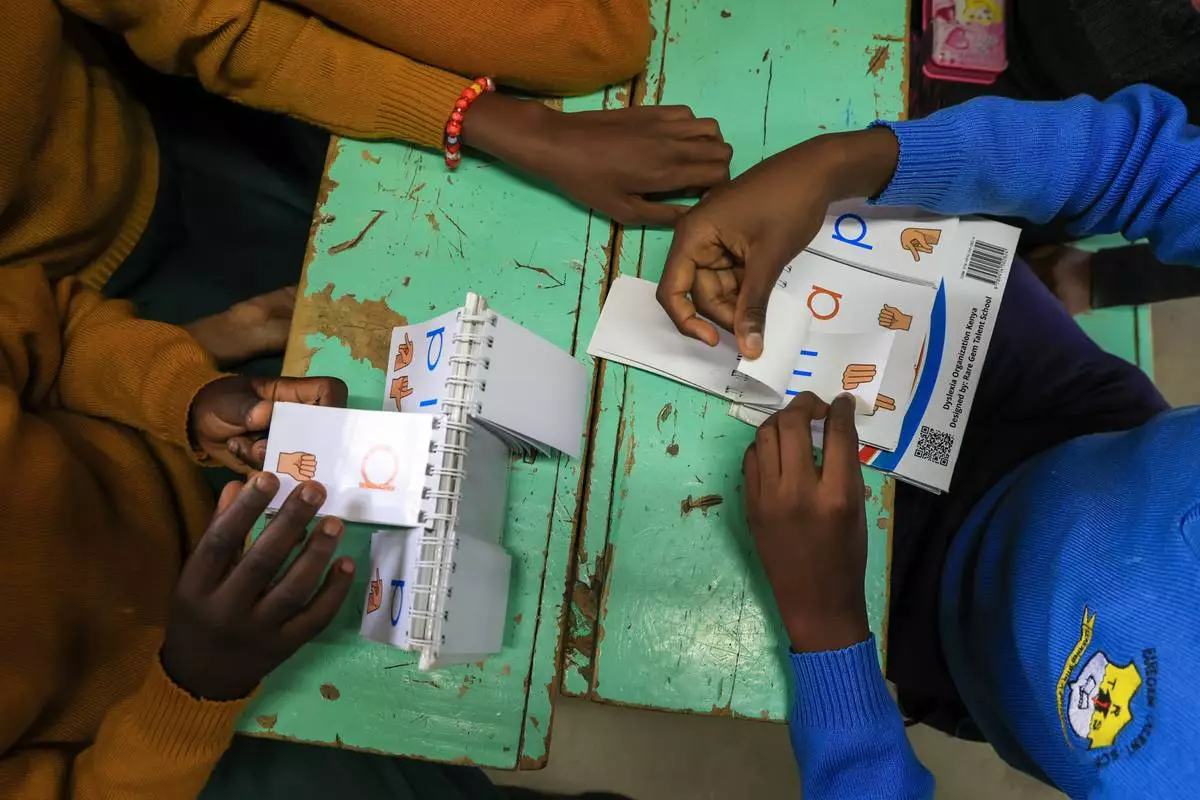

Pupils take part in an English lesson at Rare Gem Talent School, which supports students with dyslexia, in Kitengela, Kajiado County, Kenya, Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2026. (AP Photo/Andrew Kasuku)

Pupils take part in an English lesson at Rare Gem Talent School, which supports students with dyslexia, in Kitengela, Kajiado County, Kenya, Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2026. (AP Photo/Andrew Kasuku)

Dorothy Kioko, a teacher, leads a Grade 7 English lesson at Rare Gem Talent School in Kitengela, Kajiado County, Kenya, Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2026. (AP Photo/Andrew Kasuku)

Pupils take part in an arts and crafts lesson at Rare Gem Talent School, which supports students with dyslexia, in Kitengela, Kajiado County, Kenya, Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2026. (AP Photo/Andrew Kasuku)

Pupils take part in an arts and crafts lesson at Rare Gem Talent School, which supports students with dyslexia, in Kitengela, Kajiado County, Kenya, Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2026. (AP Photo/Andrew Kasuku)

Dyslexia affects around 10% of learners and represents a stumbling block to literacy. A lack of accommodation threatens to leave behind a vast swathe of a booming youth population in Kenya — and across the continent.

At his old school, “teachers didn’t understand me,” said Rare Gem student Jason Malak Atati. “This school is much better.”

Common issues for children with dyslexia are simple errors that impede literacy, like mixing up letters like “b” and “p” or even the number “9,” said Dennis Omari, a special needs educator. “The early signs to look out for are if children have issues with phonological awareness — not able to listen to exact sounds in a particular language — and when kids fail to read,” said Omari.

Rare Gem addresses blocks through what Omari calls a multi-sensorial approach to reading, with educators honing in on alternative learning styles. These could be visual, like coding word sounds with colors, auditory — teaching spelling patterns through song — or tactile, with objects used to represent word construction that forms the foundation of reading.

“You teach step by step until the learner gets what you’re teaching, not a lecture method where the teacher stands in front,” said Dorothy Kioko, a teacher at Rare Gem. “You have to have additional knowledge on how to handle them with patience.”

Rare Gem was set up in 2012 through the Dyslexia Organisation Kenya and opened with fewer than 10 learners. Today the school hosts some 210 students, mostly with dyslexia, but also accommodates those with other learning challenges like autism.

“If they are identified early and intervention given early, they improve their skills and learn to identify their talents — and they complete school,” said Phyllis Munyi, the founder of Rare Gem, who started the school after her son faced unaddressed learning challenges from dyslexia.

The school charges tuition fees of $180 a term, less than the cost of popular high-end private schools but significantly higher than the government schools attended by most Kenyan children.

Stigma and a lack of awareness, especially among parents, are the main challenges to getting children into alternative education like Rare Gem early, said Munyi. Another major discouraging factor for students is bullying that they may have faced at their prior school.

“In other, normal schools, there was a lot of discrimination, a lot of bullying,” said Geoffrey Karani, a former student at Rare Gem. Today, Karani is an art teacher at the school who sees mentorship as a key part of his job. “I’m not only teaching, I’m showing kids that I’ve been on the same journey,” he said.

Kenya has been successful in increasing access to education in recent decades, with the number of students enrolled in primary school rising from 5.9 million in 2002 to 10.2 million in 2023—outpacing population growth.

Yet education access for those with disabilities has lagged. While 11.4% of Kenyan children have special needs, just 250,000 such students are enrolled in the country’s educational institutions, according to So They Can, a nonprofit focused on increasing education access in Africa.

Rare Gem may offer a model to increasing access without dramatic overhauls to curriculums. The curriculum at the school is not bespoke, but rather a version of Kenya’s core curriculum tweaked to meet the learning needs of students with dyslexia and other difficulties, said Munyi. She added: “The curriculum was not designed as a standalone … nor is it limited to dyslexia.”

For more on Africa and development: https://apnews.com/hub/africa-pulse

The Associated Press receives financial support for global health and development coverage in Africa from the Gates Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Pupils take part in an English lesson at Rare Gem Talent School, which supports students with dyslexia, in Kitengela, Kajiado County, Kenya, Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2026. (AP Photo/Andrew Kasuku)

Pupils take part in an English lesson at Rare Gem Talent School, which supports students with dyslexia, in Kitengela, Kajiado County, Kenya, Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2026. (AP Photo/Andrew Kasuku)

Dorothy Kioko, a teacher, leads a Grade 7 English lesson at Rare Gem Talent School in Kitengela, Kajiado County, Kenya, Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2026. (AP Photo/Andrew Kasuku)

Pupils take part in an arts and crafts lesson at Rare Gem Talent School, which supports students with dyslexia, in Kitengela, Kajiado County, Kenya, Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2026. (AP Photo/Andrew Kasuku)

Pupils take part in an arts and crafts lesson at Rare Gem Talent School, which supports students with dyslexia, in Kitengela, Kajiado County, Kenya, Tuesday, Jan. 13, 2026. (AP Photo/Andrew Kasuku)

LIMA, Peru (AP) — Peru’s Congress on Wednesday elected legislator José María Balcázar as the country's new interim president, replacing another interim leader who was removed a day earlier over allegations of corruption just four months into his term.

With a majority in the 130-member legislature, Balcázar became Peru’s eighth president in a decade after defeating three other candidates. The current Congress, which began its term in 2021, has now impeached three heads of state: Pedro Castillo, Dina Boluarte and José Jerí.

Balcázar, an 83-year-old former judge representing the leftist Perú Libre party, will govern for five months before handing over power to the winner of general elections on April 12, when Peruvians will choose a new president, Chamber of Deputies, and 60 senators. If no presidential candidate receives more than 50% of the vote, the two front-runners will advance to a runoff election in June.

The past decade in Peru has been defined by chronic political instability that stems largely from the fact that ousted or resigned leaders lacked legislative majorities, leaving them vulnerable to lawmakers who have broadly interpreted a constitutional article to remove presidents for “moral incapacity.”

In October 2025, Jerí was serving as president of Congress and was next in the line of succession to replace Boluarte, who had no vice presidents. His sudden downfall following undisclosed meetings with Chinese state contractors has once again left the nation seeking a steady hand to reach the finish line of its democratic cycle.

THIS IS A BREAKING NEWS UPDATE. AP’s earlier story follows below.

LIMA, Peru (AP) — Peru's Congress on Wednesday will choose the country's eighth president in a decade to replace the newly ousted former leader José Jerí, with four lawmakers who are largely unknown to the public vying for the position.

The candidate who secures the most votes will lead the nation as interim president until July 28, when they will transfer power to the winner of a general election scheduled for April 12.

The revolving-door presidency in Peru reflects a political crisis fueled by a lack of legislative majorities for leaders. Lawmakers have frequently used a broad interpretation of a constitutional article regarding “permanent moral incapacity” to remove sitting presidents.

On Tuesday, Congress voted to remove Jerí after four months in office. The removal followed revelations regarding his undisclosed meetings with Chinese business owners, including a state contractor. Jerí asserted he was merely coordinating a Peruvian-Chinese festival.

The Public Prosecutor’s Office has launched two preliminary investigations into Jerí over allegations of illegal sponsorship of private interests and influence-peddling to the detriment of the state.

Congress announced Tuesday that four candidates had officially registered for Wednesday night's vote. Levels of support for each were unclear. To win, a candidate must receive a majority of the votes from those present. If no majority is reached, the two leading candidates will enter a runoff, where the person with the most votes wins.

The front-runner is thought to be María del Carmen Alva, a 58-year-old lawyer nominated by the conservative Popular Action party. Alva, who previously served as speaker of Congress, comes from a family that holds significant interests in the agro-export sector, specifically in companies that ship asparagus to international markets including the United States.

Another candidate is Héctor Acuña, a 68-year-old engineer representing the conservative group Honor and Democracy. He has significant private sector experience but is often viewed as having less traditional political seasoning than his rivals. He is the brother of César Acuña, a millionaire former governor and a presidential candidate for the April 12 election under the Alliance for Progress banner. The party previously provided key support to former presidents Dina Boluarte and Jerí.

The other candidates are José María Balcázar, an 83-year-old former judge representing the leftist Perú Libre party, and Edgard Reymundo, a 73-year-old sociologist from the leftist Bloque Democrático.

Jerí’s successor will confront a surge in murders and extortion that continues to devastate small business owners and the working class.

Various political groups are demanding firm guarantees for a transparent election, which also will elect a new Congress consisting of 130 members of the Chamber of Deputies and 60 members of the Senate.

Follow AP’s coverage of Latin America and the Caribbean at https://apnews.com/hub/latin-america

Police patrol near the government palace, the office of the president, in Lima, Peru, Wednesday, Feb. 18, 2026, the day after lawmakers voted to remove interim President Jose Jeri from office as he faces corruption allegations. (AP Photo/Guadalupe Pardo)

A couple sits on a bench at the main square by the government palace, the office of the president, in Lima, Peru, Wednesday, Feb. 18, 2026, the day after lawmakers voted to remove interim President Jose Jeri from office as he faces corruption allegations. (AP Photo/Guadalupe Pardo)

A shoe shiner passes a newspaper to a client near the government palace, the office of the president, in Lima, Peru, Wednesday, Feb. 18, 2026, the day after lawmakers voted to remove interim President Jose Jeri from office as he faces corruption allegations. (AP Photo/Guadalupe Pardo)